The website Remix provides news in English on Central Europe, with a soft spin much alike Viktor Orbán’s agenda. Behind it, Átlátszó has discovered a foundation run mostly on the money of the Hungarian government, as well as a long line of right-wing US campaign experts advising Fidesz with ties to the Republicans.

by Márton Sarkadi Nagy, Átlátszó

Since I’ve been working on this article about Remix, an online news site, and the political and historical background behind it, whomever I show the front page of the site don’t show much interest. At first look, everyone sees a timely, English-language online medium of modern visual design providing news on Central and Eastern Europe.

At the time of writing this, the front page of Remix, originally founded two years ago, is filled with news items of the Visegrad Four: Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, plus some current events mainly in other Central European countries. There’s nearly no standout signs that Remix is in fact one of those mouthpieces that are financed by Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán’s regime that carry sometimes propagandistic, sometimes disinformative messages to the international public.

What is more, the background of the owner and of CEO Remix lies in a decades-long practice of political advice of a US Republican orientation received by Orbán and his Fidesz party.

A spectator well versed in the peculiarities of Hungarian political media can, however, glean several telling details from the front page. The titles for the news items sometimes belie an underlying worldview toted in local media friendly with the government. The story at the top refers to Central European University or CEU — an institution hounded out of Hungary a few years ago — as the same derogatory nickname, “Soros University”, by which Hungarian governmental figures regularly refer to it.

Among several stories dealing with serious topics in the realms of politics, business or culture, news pieces dealing with migration seem to be inexplicably abundant. For example, right next to a lengthy article on defence procurements by the V4 countries, there is one on two migrant people getting apprehended on a Czech highway — like the two topics could bear the same importance. Some news are tagged “migrant crime”. The expression echoes “gipsy crime”, a racist concept championed by the Hungarian far right and “jew crime”, an analogue tag used on the neonazi Kuruc.info news site to tag some news items.

Part of the front page at Remix. Source: rmx.news

And in the downmost news block, the front page of Remix displays parts of an English-language news show that used to run on Echo TV. Echo, a news television which has been a longtime ally of Fidesz usually noted for its equally amateurish and radical tone was discontinued a few years ago, while being a part of the KESMA media group friendly with the Hungarian government.

Earlier this year, I wrote a lengthy piece about V4NA, a self-styled news agency that disseminates messages of Orbán’s propaganda machinery while disguised as a global media product.

Remix, while obviously tries to cater to a more conscious readership than the somewhat ham-fisted V4NA, still shares a problem with the so-called news agency: disinterest. However nicely dressed up and written in perfect English journalese, Remix’s material seems to leave only a tiny social media footprint in the English-speaking information sphere. During September, the three top articles published on Remix gathered only 6.6., 6.2. and 1.1 thousand total interactions (that is, likes plus shares plus comments) on social media, according to data gathered by Newswhip.

The ease by which Remix fits the look of the current international milieu of news sites, dominated by a culture lead by US publishers, is not a coincidence. The owner of FWD Affairs Kft., Remix’s publisher is Patrick Egan, an American politician consultant now living in Budapest.

There’s been not much written formerly about Egan, now 51. He was reportedly a speaker at the regular Fidesz jamboree in Tusnádfürdő, moderated a public debate at Terror Háza, which belongs under Orbán-ally Mária Schmidt, four years ago his company received a 14 million HUF contract from Miniszterelnöki Kabinetiroda, and his company holds a key role in English-language, government-financed news site Transylvania Now.

But there is much more to learn about Egan, who has strong ties towards the US Republican Party and its formally non-partisan ally, the International Republican Institute or IRI. It is particularly ironic, that, according to their website, in 2016 IRI has “launched a new program aimed at countering the increasing threat of Russian soft power and propaganda”, since the narratives pushed by media organisations considered close to Orbán often share Russian disinformation narratives.

In a consultancy firm active in Hungary, Egan is working with a certain Sean Tonner, another US political consultant, who advised Fidesz during the noughties.

Since Fidesz’s landslide electoral victory in 2010, much has been made about Orbán’s connection to Arthur J. Finkelstein, a Republican campaign strategist who made a career working for the Republican side of the US political arena and his right hand man George Birnbaum. Less people now that they are but the last in a long line of political advisors originating from around the Republicans.

But in this tradition, it is surely a novelty if the expert sent to educate the friendly local yokels is turned and sent back to pollute the English-language information sphere with disinformation. Apparently, this is exactly what seems to be happening in Egan’s case, as according to the “about” section of Remix, it is funded in part by the foundation Batthyány Lajos Alapítvány (BLA).

BLA was originally established by a group of friends and allies of former PM József Antall in 1991. After Antall has passed away and no successor has taken up his politics, the foundation has gone stale, only for the Orbán administration to rain money on it in recent years.

I’ve reviewed BLA’s recent financial reports and found that, though the foundation itself is formally independent of the government, lacking meaningful other income, in effect it serves as a conduit for channeling donations from the Hungarian government to other entities. BLA’s main source of funding is Miniszterelnöki Kabinetiroda, the part of government run by Antal Rogán that is also responsible for channeling advertising money. In 2019, they received 3,534 billion HUF from state coffers, which were then redistributed to more than a dozen various other organisations.

We don’t know how much money FWD Affairs received from BLA. But there apparently aren’t any ads on the site which also shows no sign of a paywall or any other system allowing for reader contributions.

Yearly financial reports from of the publisher show dynamic growth and a return on sales of nearly 50 percent — this rate of profitability belongs to fairy tales for even those media companies that operate with a recognisable business model.

I’ve asked BLA about the amount of their financing, as per my information the questions have been forwarded to the leadership of the foundation, who so far didn’t answer. I’ve asked Egan several things, for which I’ve received no reply.

One of these questions was about Klára Vizér, a former Fidesz politician who represents a personal connection of unknown substance of Egan’s to the party’s ranks. From 2010, Vizér was a deputy mayor in the 15th district of Budapest, but later lost his position in the leadership after several rounds of tumultuous political infighting at the local chapter.

Another interesting fact formerly gone unreported is that Egan has been active around politics in Hungary since the noughties. In 2005, Egan gave an interview to Hungarian daily Magyar Nemzet, where he was identified a former Iraqi country director later promoted to the Central and Eastern European directorship of IRI and dubbed a “democracy maker”.

“Egan is one of those American young men, who use their determination and careers in service of an American effort to spread Western-style democracy all over the globe, be it the Eastern Europe of the nineties or the Middle East at the outset of the new millennium” — wrote Magyar Nemzet, which was back then as well as now a close ally of Fidesz.

It is worthy of note that around media friendly with Fidesz, the practice of “democracy making” has not been often praised like this. For example, in the same year, 2005, a feature in Orbán-friendly weekly Magyar Demokrata wrote at length about the so-called colour revolutions very much along the lines of regular Russian narratives, which suspected the United States and in particular IRI behind these.

In 2008, Magyar Hírlap reported on a public debate at the Szabad Európa Klub, “of those interested in conservative foreign policy”, where, in addition to Jeffrey Levine, who was deputy head of mission at the Budapest embassy of the United States at the time, Egan — who was identified as the president of the organisation of Republicans living in Hungary — also spoke about the upcoming US presidential elections.

Another news report from 2009 shows that with the Hungarian elections looming, Egan was also immersed in the topic. At the summer university of the youth organisation of Fidesz at Balatonszárszó, the same two Americans held public lectures, but while Levine restricted himself to international security policy, Egan talked about campaign strategy. (In their report, Magyar Nemzet identitied him as a “Republican politician of Central Europe”.)

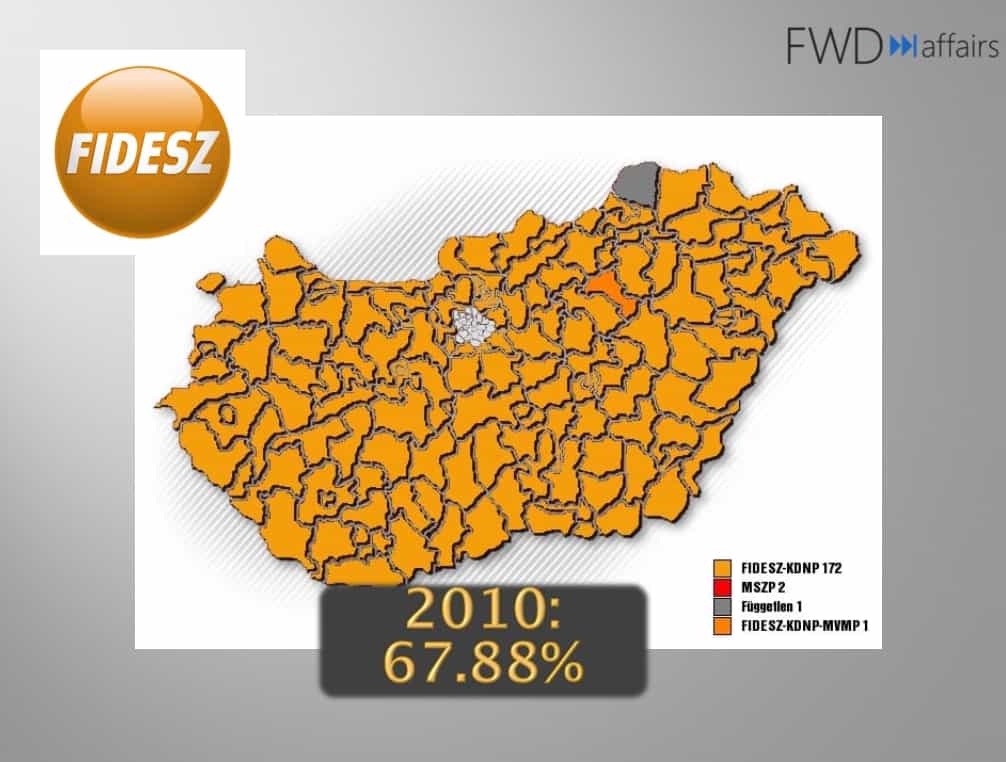

On the website of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS), a foundation close with the Christian Democratic Party in Germany, one can find concrete evidence. A presentation prepared for a conference on political communications bearing Egan’s name makes it obvious that FWD Affairs took part in the 2010 campaign of Fidesz.

Part of the presentation. Source: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung / FWD Affairs / Patrick Egan, Sean Tonner

The presentation is about methods for directly contacting voters and a technology called tele-town-hall; this latter means a technology that dials thousands of households simultaneously and creates an enormous conference call, or a live “town hall meeting” with thousands of citizens over the phone. The technology on one slide is illustrated with a photo with István Tarlós’s campaign poster for the Budapest mayoral elections.

“As managing partner of FWD affairs” — states a short bio of Egan on the website of KAS — he “has more than a dozen years of experience working on political transitions in Europe and leads the company’s efforts to bring to the continent the latest tools in political and public affairs to identify and engage supporters…. He has worked directly with mayoral and parliamentary candidates and party leaders to develop competitive communication and direct voter contact methods, most recently in France, Hungary and Romania.”

In addition to Egan’s, the presentation bore also a certain Sean Tonner’s name. According to the same website, Tonner, “a pioneer in the modern direct-contact and voter mobilization operation, has worked on numerous political campaigns in the U.S. and abroad including Bush-Cheney, Bill Owens for Governor, Ben Nighthorse Campbell for Senate, Mike Coffman for Congress, and numerous local and state efforts… Most recently, Tonner has been working with clients in Central Europe.”

According to another public resume of his, he has worked at least on one campaign of Orbán. I’ve sent Tonner some questions, but so far he hasn’t replied.

Originally, Tonner was the founder of Phase Line Strategies LLC, a company that was in turn a partner of Egan between 2010-11 in FWD Affairs. The earliest mention of him in relation with Hungary is from 2005: a US news piece mentions that Tonner and Rich Beeson, another Republican-leaning advisor were then on their way to Budapest to advise leaders of Fidesz — “the closest thing to the Republicans over there”, according to Tonner —on voter mobilization.

The name of Tonner’s traveling mate later leaked into Hungarian media: in 2008, Index reported that Rich Beeson, identified as a “director of the Republican Party”, was coming to Budapest to advise and train Fidesz hopefuls in case of a snap election.

Egan and Tonner are both currently partners in Interactive Global Solutions (IGS), another US advisory firm, according to their website. The site also mentions a Budapest presence, which casts some doubt over whether Patrick Egan really is the American expert of Fidesz, or the guy who can solve things for his Republican friends in Budapest? IGS, on their website, prides itself over solving a tax issue of their client, a “large US Oil and Gas Company”, by “negotiating a policy change” and “helping elected officials” in Hungary in under six months.

Átlátszó’s review of IRI’s involvement in Hungarian politics has turned up a history going back to 1990, when the organisation, which was then named the National Republican Institute for International Affairs, donated thousands of dollars to MDF, the main initial right-wing democratic party on the local political spectrum at the time of the transition to democracy.

At the time, Fidesz was considered a liberal party, but at least after 1994, with MDF falling from power and Orbán’s party disappointing at the elections, Fidesz began to move towards the right. According to news reports of the era, one Daniel Odescalchi, another US political advisor played a key role around these events.

The name Odescalchi has a history in Hungary: the local branch of the old Italian banking family has elevated among the aristocracy of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Ironically enough, the former mansion of the Odescalchis in Budapest now belongs to the family of former PM Ferenc Gyurcsány, the most visible political opponent of PM Viktor Orbán, and Gyurcsánys wife, Klára Dobrev, another key opposition politician.

Daniel Odescalchi, a US political advisor who also speaks Hungarian, has turned up as advisor to József Antall, the MDF PM at the time in 1992. According to Odescalchi’s online available field report from the time, he had to tackle peculiar issues among the Hungarian politicians unfamiliar with the nuts and bolts of free elections. MDF people, in general, tended to dismiss any polling results, believing that the pollsters were all under “liberal” influence. Elected MP’s weren’t keen on actually going to their respective electoral regions and meeting their voters.

As opposed to the campaign methods in the US at the time, Odescalchi was surprised to find that the main force in government didn’t have any database to facilitate voter outreach. As a solution, he implemented mass mail surveys, and a central office supporting the campaigns of various local candidates.

But he was also drafted in to help with particularly sensitive matters as well. According to the website of Strategic Advantage International, Odescalchi’s consultancy firm, they were behind the communications team that “helped the government of Hungary when the international community accused it of illegally selling arms to Croatia during an arms embargo during the Bosnian War”; and they were also assisting the government “in developing a campaign to sell the concept of privatization” to the Hungarian public.

After Antall’s untimely death, his replacement Péter Boross basically greeted Odescalchi with the following words, according to the advisor’s field report: “You do your campaign, but leave me out of it.” Odescalchi had a conflict with the MDF mainstream as well and left their employment in 1994.

But he didn’t leave Hungarian politics. After postcommunist MSZP won the elections and pulled liberal SZDSZ into a coalition government, Odescalchi played a key role in the pulling together of the plethora of beaten right-wing parties that later resulted in their 1998 win. That was the time he also started to work with Orbán.

“When I first met Orbán I worked with the Antall Government. Once MSZP won the election, I created and ran a program called Survival in a Democracy to support the center-right parties. At the time, Fidesz, and their leader, Viktor Orbán, were rising stars. This was probably 1994/95. Orbán was seen as a darling of the West due to his anti-communist, anti-authoritarian rhetoric” — wrote Odescalchi in an email to Átlátszó.

“The goal of Survival of a Democracy was to prop up these new parties who, at the time, had difficulty getting monetary support. Survival in a Democracy received funding from 13 international organizations who wanted to make sure Hungary had a robust and competitive multi-party system. They also want the center-right to be able to compete in elections.”

Odescalchi’s job was to create public opinion polls that were paid for by Survival in a Democracy, and then present the polling results to the center-right parties. They would also present strategies that the parties could implement based on polling.

“Fidesz was a priority of the program” — Odescalchi wrote.

The program said to be supporting a multiparty character of the Hungarian democracy, however, became a topic of multiparty mudslinging in Budapest, after a leaked message allegedly posited that Americans, who would like to finance a centre-right alliance, would like to see less of the Smallholders Party and their demagogue, but popular leader József Torgyán and more of SZDSZ — which incensed MDF folks, who harbored deep resentment against the liberals.

Contemporary press reports do not speak of 13 organisations supporting the program. In a 1995 article in Magyar Nemzet, there are only two supporters named:

“Strategic Advantage International Ltd., an American political consultancy institute — which doesn’t hide its aim to strengthen Hungarian conservative parties — held the fourth gathering of [the program] with the support of the International Republican Institute and Batthyány Lajos Alapítvány.”

In 1995, Odescalchi left Hungary to join Steve Forbes’ ultimately unsuccessful campaign for the presidency, but returned again for some time to Budapest. We don’t know when he stopped advising Orbán, but his ideas, apparently, foreshadowed Fidesz politics for years.

In 1996, he told Magyar Nemzet: “We still support the idea for these parties to establish an alliance. I made up the whole program — that these opposition parties should come together — because they are much stronger together.”

Notably, after the 1998 elections brought Orbán’s first stint as PM, his party started to employ various political plays to break their rivals — which were also their nominal allies either in government or in belief. By various methods and to differing extent, several right-wing parties met such fate, including both MDF and the Smallholders. Their voter base was integrated into Fidesz, which grew big enough in size to directly rival the left-liberal block afterwards.

Fidesz even changed its official name in the 2003 aftermath of these events to include “alliance” instead of “party”. They haven’t changed the name since.

Written by Márton Sarkadi Nagy. Hungarian original was also written by Márton Sarkadi Nagy for Átlátszó. Cover photo: Remix