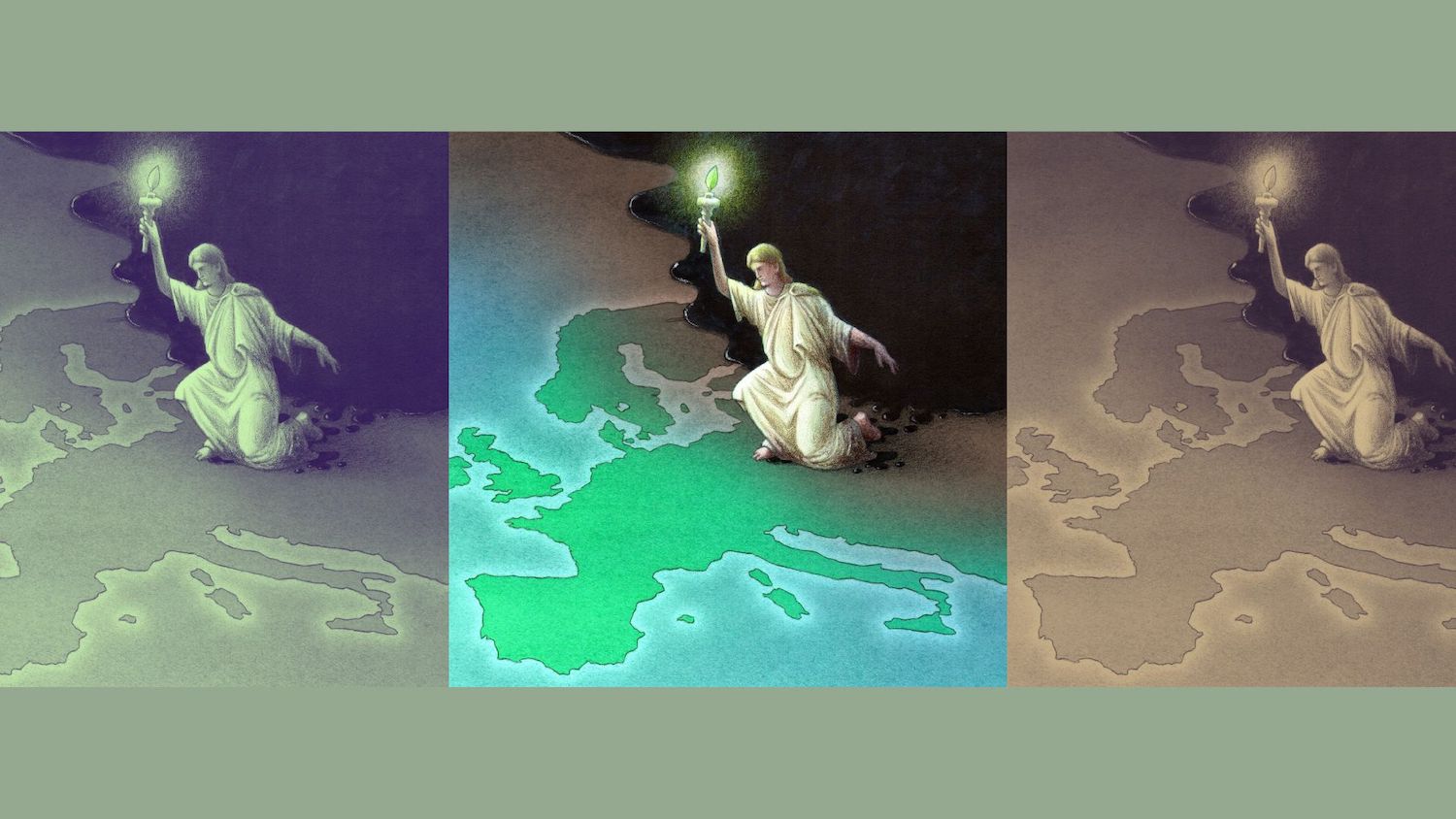

In the next years to come, Europe will be tormented by overlapping conflicts of varying nature, that will put additional pressure on the democratic setup of the Union and its immediate neighbourhood – writes Wojciech Przybylski, Editor-in-Chief of Visegrad Insight, in the Executive Summary of new report: War and the Future of Europe.

As the Russian aggression on Ukraine is expected to continue despite an accelerated decay of the aggressors’ power, several other global pressure points – ranging from environmental and health to digital and demographic issues – are already converging. The tensions between autocratic and democratic governments are manifesting globally, and the subsequent effects are increasingly pronounced for Europeans. Consequently, the European Union will need to rehabilitate its quest for autonomy – understood not as a pet project of anti-American isolationists but as a democratically propelled quest for power to support joint efforts for the stability of the liberal world order.

The following pages project four different scenarios which map out how European democratic security will be challenged by 2030 and how to prepare for it. When this strategic foresight project began – twelve months ago – it was more singularly focused on amplifying Central European intelligence and voices with respect to the themes of the Conference on the Future of Europe. However, it has been irreversibly impacted by the tragic events in the east of Europe.

As we publish, our future is being decided on the battlefields of Ukraine where fierce fighting as the result of a brutal Russian invasion has materialised into the first major European war of the twenty-first century. Without a doubt, this conflict has already redefined both NATO’s and the EU’s policies – triggering further enlargement, military exports and energy transformation – and its outcome is expected to bear long-term consequences not only for the enduring European peace project but also for nations stretched across the globe.

The following scenarios and appended materials. The war is a moment of clarity that verifies several assumptions about the strategic direction of the EU and Europe overall. Yet, even though it is a major and imminent factor, it is also a catalyst for change on a number of less pronounced developments which have been shaping European fates for years. While Ukraine’s fight for a free Europe is currently overshadowing major themes like the rule of law, climate change or the future of transatlantic relations, it has only amplified their importance.

At the same time, the illiberal drive led in Central Europe primarily by Budapest and Warsaw has eclipsed the much-needed voices from the region on the future of Europe during the course of probably the biggest deliberative democracy initiative in the world – the Conference on the Future of Europe that has concluded in spring 2022.

l have been generated during civil-society-powered foresight exercises. Together with partners across the EU, Visegrad Insight has generated a mind map shaped by the Central European voices in the debate about the future of Europe that extends much further beyond the process officially concluded by the EU’s institutions. By means of extensive discussions and broad inquiry, it gives opportunities to actors that may not be heard through conventional and state-led channels.

The project has been carried out in partnership with the Bratislava Policy Institute (Slovakia), Euro Créative (France), European Forum Alpbach (Austria), Fondazione Di Vagno (Italy), Forum2000 (Czechia) and Open Lithuania Foundation (Lithuania). It is co-funded by the European Commission’s Europe for Citizens Programme. The development of this report has been also possible thanks to the generous support of my Europe’s Futures Fellowship at the Institute of Human Sciences – IWM in Vienna and the ERSTE Foundation.

This collaborative effort has materialised into four distinct scenarios. Using the insights from over a hundred civil society leaders and experts from the region, who took part in our foresight workshops, we explain how Europe’s strategic autonomy might be forever lost even before it is fully acquired. At the same time, we indicate a patchwork mode of European cooperation that is plausible in light of common security challenges. Taking concerns over demography seriously, we stipulate the effects of a European social contract that allows sustaining more defence-related burdens. Finally, looking from yet another perspective, the last scenario presents the potential pitfalls of a reformed and enlarged EU that falls prey to the next generation of populism.

Our project challenges an image of recalcitrance and limited input associated with the CEE region with the aid of relevant scenarios for the debate on the EU’s future. While it often paints a dark picture, it does so merely to reinforce the block against the backdrop of ongoing and forthcoming difficulties.

Recommended Directions

Drawing from these perspectives, I should underscore that Europe is not alone. Even though its transatlantic link has been tested heavily by the autocratic leadership style practised across the pond, the value-driven community of democracies stands united across the globe. There are allies in much more distant places, which Europe can rely on and which it must also support to upkeep a world order and economic links that sustain it.

Europe needs to reform its position on strategic autonomy, understood as a long and never complete path, to fulfilling its potential. The Union must increase its potential to prevent and, when needed, resist aggressors wishing to undermine free societies. Before it even builds a common army, it must invest in all public sectors – from energy to civic education – that sustain its freedom to act in defence of a democratic setup. It should also not reinvent the wheel, but move in that direction bearing in mind its own strategic shifts that have been making us all more resilient.

The EU must also think politically, understanding that while its institutions have been designed as merely bureaucratic vessels of the idea of post-war peace, Europe has been evolving ever since to be a more political actor involved in domestic and external power struggles. With such hindsight, it must plan better checks and balances mechanisms when reforming or enlarging in the future.

Read more and download the report on visegradinsight.eu.

Wojciech Przybylski is a political analyst heading Visegrad Insight’s policy foresight on European affairs. His expertise includes foreign policy and political culture. Editor-in-Chief of Visegrad Insight and President of the Res Publica Foundation. Europe’s Future Fellow at IWM – Institute of Human Sciences in Vienna and Erste Foundation. Wojciech also co-authored a book ‘Understanding Central Europe’, Routledge 2017. He has been published in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, Journal of Democracy, EUObserver, Project Syndicate, VoxEurop, Hospodarske noviny, Internazionale, Zeit, Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, Onet, Gazeta Wyborcza and regularly appears in BBC, Al Jazeera Europe, Euronews, TRT World, TVN24, TOK FM, Swedish Radio and others.

The views and opinions expressed on our blog are those of the authors, representing a wide range of viewpoints, and do not necessarily reflect the position of VSquare or our affiliated organisations.