Access to public information is one of the most important checks on power for journalists and citizens alike. In theory, all Central European countries have a transparency law. In practice, they do not always serve their purpose.

This collaborative report is based on research from seven investigative outlets, which constitute The Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project: Investigace.cz (Czech Republic), Bird.bg (Bulgaria), Frontstory.pl (Poland), Rise Project (Romania), Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak – icjk.sk (Slovakia), Átlátszó (Hungary), Context Investigative Reporting Project (Romania).

Government transparency laws were introduced in the Czech Republic in 1999, in Romania in 2001 and in Poland in 2002.

In Slovakia, the Act on Free Access to Information (The Freedom of Information Act) number 211/2000, commonly referred to as “the two hundred and eleven,” was put in place in 2000 during the first government of Mikuláš Dzurinda, who replaced autocrat Vladimír Mečiar and was trying to get the Slovak Republic back on track with Euro-Atlantic integration. The Freedom of Information Act was passed as a part of transparency reforms and was one of the strongest FOIA acts worldwide at the time.

Since then, there have been numerous attempts to weaken the act. These include increasing the number of situations in which citizens are not entitled to information on decisions made by state agencies or to information on companies created by those state agencies and self-governing bodies. Others have attempted to cancel the possibility to fine the state administrators who do not respect FOIA requests. Fortunately, all of these attempts were unsuccessful, mainly due to pushback from the civic sector.

The current transparency law in Hungary was adopted in 2011. Last year, the law was modified at several points, making it somewhat easier to obtain public information. The modification of the law was part of a process in which the Hungarian government and the European Commission intended to come to an agreement regarding Hungary’s frozen EU funds.

The modifications included making court procedures shorter and making it such that data owners were limited in their ability to charge for provision of their own data (data owners can now charge smaller amounts in the scenarios where they are still able to charge).

In all our countries, information that is classified or related to national security or defense is exempt from the law. Also exempted are trade secrets and information related to the privacy of an individual.

Public institutions often use the European privacy law GDPR as an excuse not to provide information, even though the information is of public interest. For example, in Romania, public institutions often deny access to a certain document, arguing that there is personal data in the document. However, legally, information related to the personal data of citizens can become a matter of public interest if it affects the ability of that person to perform a public function.

Timeframes to respond to requests for access to public information vary widely. In Slovakia, it’s eight working days, with a possibility to prolong to 15 working days. In the Czech Republic it is 15 days, but in special circumstances, it can be prolonged another ten days. In Romania, public authorities and institutions are obligated to respond within ten days or, depending on the case, within a maximum of 30 days from the date of registration of the request. In Poland a request should be processed “without undue delay,” but no later than 14 days from the date of the request. If it doesn’t happen, the entity should make clear the reason for the delay and the date by which it will make the information available, but no longer than two months from the date of the request.

In Hungary, the deadline is 15 days, which can be extended by another 15 days. However, during the COVID pandemic, a special law was introduced: public bodies had 45 days to respond, which could be extended by another 45 days. This was in force from Nov. 25, 2020. until Dec 31, 2022, making it a nightmare to request public information. In theory, extending the deadline is only possible if a large amount of data is requested or if the completion of the request requires very significant efforts from the data owner. However, FOIA requests are often delayed without real reason.

So that’s the theory. What about in practice in the real world? All of our journalists have experienced some difficulty in obtaining presumably public information.

Governments’ many tricks

The most optimistic outlook is in Slovakia. Here, the problems were mostly in cases involving personal information or state secrets or cases being investigated by the police at the time. FOIA requests were also sometimes denied on the grounds of protecting intellectual property.

In the Czech Republic, the law can be difficult to enforce, because the authority that is supposed to supervise it is reluctant to do so, which means that sometimes the only way to make an institution provide the information is to go to court, a process that takes several years.

There were two notable cases of journalists fighting for information that were ultimately decided by the Constitutional Court. One was on COVID data; the second, on police crime databases. In January 2023, the Constitutional Court decided that the National Health Information System has to provide statistics to journalists and the public regarding the number of people who died of Covid-19. The court noted that as a general rule, information should be provided unless there are serious reasons for refusing the request, which must always be clearly justified.

In 2016, the police demanded nearly CZK 26 million from a data journalist with iROZHLAS.cz to fulfill a request for data about crime. In June 2021, the Constitutional Court ruled that such a fee would make it virtually impossible to access the information. “The obliged entity should look for ways of maximally complying with the submitted request and not for reasons to prevent it from being granted,” wrote one of the judges in the ruling.

According to the latest GRECO (The Group of States against Corruption, established by the Council of Europe) report, one of the problems with the law in Romania is that publicly significant information is not regularly published on the internet, despite legal requirements that it be so. Moreover, GRECO requested an independent mechanism to examine complaints against authorities refusing to disclose public interest information.

In one case, researched by Context.ro, the Romanian Foreign Ministry was presented with the simple question of if the Romanian government used spyware. The ministry was tasked with providing answers to a list of questions sent by the European Parliament committee investigating the use of spyware across Europe. Romania, as with other states, refused to cooperate or to answer directly whether it had been using spyware on its own citizens. Context.ro filed a FOIA request for the results of the questionnaire, since several Romanian authorities had filled it out. The ministry denied access to this information. The case went to the Bucharest Tribunal, which also ruled in the government’s favor.

Context.ro published a series of revelations based on information it received from the Healthcare ministry after a lengthy lawsuit. The investigation shows that half of the electrical wiring in Romanian hospital’s intensive care units (ICU) is outdated. In some cases, faulty wires or old electrical grids were the cause of huge fires that led to the death of over 40 Romanians in the last decade. The Ministry of Healthcare refused to provide reports on the status of ICU electrical wiring. Context.ro filed a suit and, after a legal battle lasting 532 days, received the documents and informed readers. Context.ro built an online database that now shows the status of each hospital ICU in Romania.

The online database crated by Context.ro that now shows the status of each hospital ICU in Romania

In Hungary, Atlatszo journalists have been trying in vain for more than seven months to find out from relevant authorities how often fires occurred in Hungary at waste facilities in recent years. In reply to our FOIA requests, the National Directorate General for Disaster Management has claimed, several times, that they do not collect such data. This is a rather peculiar statement, since they themselves operate an event calendar on their own website that contains all fire events. However, it is not possible to properly search the database, and so journalists asked for the data in a separate file, which they never received. In the meantime, it turned out that the Ministry of Interior requested a very similar dataset from the National Directorate General for Disaster Management—and that, unlike Atlatszo, they received it. Atlatszo tried to obtain this specific dataset from both institutions: the ministry claimed they are not the owner of the data so they can not release it, and the directorate general claimed once again that they “do not collect such data.” In the end, with the help of a reader, journalists scraped all data from the public online event calendar of the National Directorate General for Disaster Management.

Átlátszó also tried to obtain information on groundwater investigations that have been carried out at the Samsung factory in Göd since 2018. However, the Budapest Disaster Management Directorate did not send journalists any data in response to their FOIA requests. Atlatszo thus went to the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information. The investigation was inconclusive. Then, last summer, journalists filed a lawsuit against the battery factory for water monitoring data. They won the lawsuit and finally received the requested documents in January. The result was shocking: no water samples have been taken from the monitoring well on the factory site since 2016, and the well was, in fact, buried in 2018. This reveals that Hungarian authorities are not testing groundwater for hazardous substances used in battery production, despite the fact that independent testing has found a toxic solvent—also used in the battery manufacturing process—with fetal harm potential in wells near the factory.

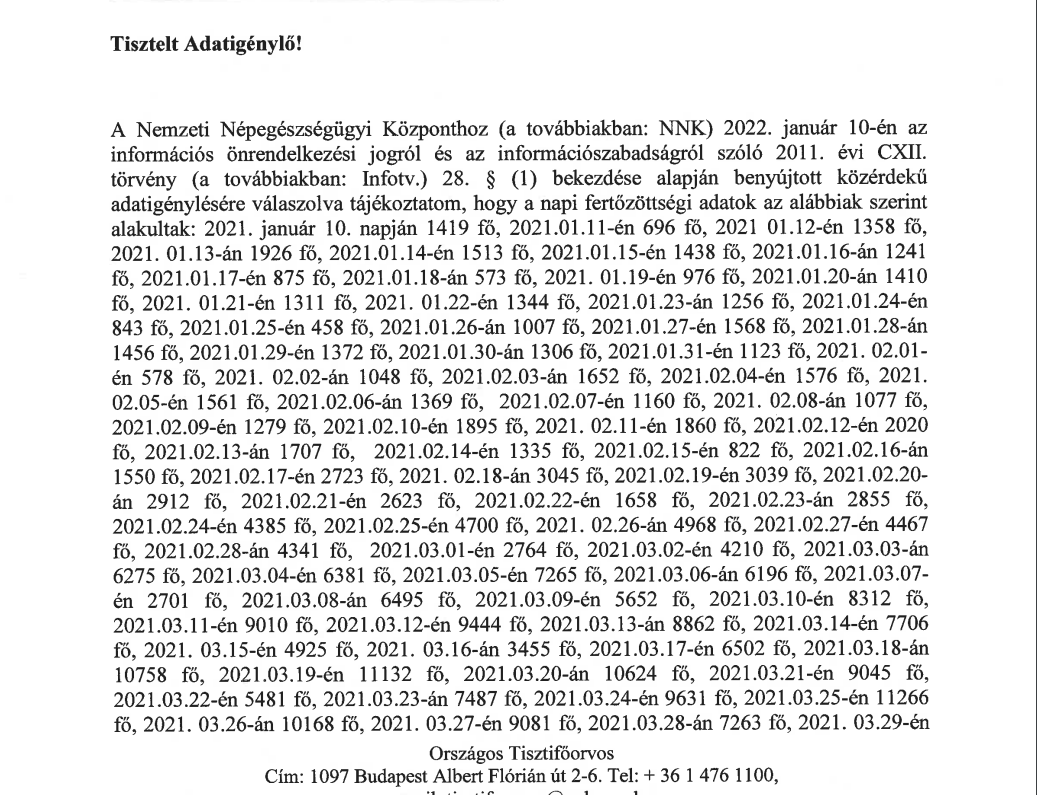

And sometimes institutions use another trick: They give journalists the data, but in an unusable format. During the pandemic, in May 2022, Atlatszo wanted to obtain information on how many of the daily registered cases of coronavirus infection were from vaccinated individuals and what type of vaccine they received. They requested this information from the National Public Health Centre. After 90 days, the office sent us the data in a pdf file like this: https://atlatszo.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/mullercecilia2.png and as a scanned, black and white chart: https://atlatszo.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/mullercecilia.png, which was simply not possible to interpret. When the journalists published this in an article, the relevant authorities sent the chart over in color (but still as a scanned pdf document).

An example of data obtained by Atlatszo.hu

In Poland, many public institutions have learned over time to use legal provisions to either delay or refuse to release public information. One way of not answering is to consider the information requested as so-called processed information (i.e., requiring additional work to collect) and then call on the applicant to demonstrate a particularly important public interest. Frontstory.pl was, for example, denied public information from State Forests under this pretext.

If public information is denied, a citizen has the right to appeal the decision in an administrative court. This is a lengthy process, the outcome of which depends on the case law of the courts. It’s also a very lengthy procedure, and can take anywhere from several months to several years.

Watchdog Poland, which specializes in the right to public information, reports that the state-owned companies and their foundations are the entities that most commonly reject requests for release of public information. Requests for information on marketing expenditures of state-owned companies and their foundations are often met with refusal. One recent example comes from the campaign to commemorate Pope John Paul II on Polish State Railways trains. Conductors and train managers had yellow and white pins pinned to the lapels of their business jackets that day, and those who normally wear the PKP Intercity badge replaced it with the pope’s flag. However, the initiative to distribute cream puffs (pastries associated in Poland with John Paul II) to passengers attracted the most interest. There was no information about their manufacturer, composition, or allergens, or even about the storage conditions.

The cost of purchasing the pastries was also unknown. Emotions may have been further inflamed by the fact that the campaign was part of a heated public discussion that began after the broadcast of a television report on the evaluation of the past activities of Karol Wojtyla, who later became Pope John Paul II. Representatives of the ruling party, exercising political oversight over state-owned companies, publicly criticized the tone of the TV reportage.

The state-owned company’s foundation responded that “the PKP Group Foundation is not obliged to make public information on the operational details of such projects, related, among other things, to the costs and principles of cooperation with other entities, which is due to the fact that the PKP Group Foundation is not an entity obliged to make public information available.”

In another particularly vivid example, it took three and a half years for Polish journalist Jan Kunert to get information about contracts that the Polish National Foundation (PFN) had signed. PFN was established in 2016 with the aim of promoting Poland in the world and its operation was made up of state-owned companies. Its annual budget at the beginning of its operation was PLN 100 million. Ultimately, it was to reach half a billion zlotys.

Jan Kunert filed a complaint with the Provincial Administrative Court in 2017. In 2018, the Provincial Administrative Court agreed with the journalist. The Polish National Foundation appealed the decision to the Supreme Administrative Court. In 2021, the Supreme Administrative Court upheld the lower court’s decision. The Polish National Foundation argued that corporate secrecy did not allow for the release of information about its contracts. In a verbal justification of the verdict, the court stressed that “it cannot be said that the funds at the foundation’s disposal are public funds within the meaning of the Public Finance Act, but nevertheless it can be assumed that it manages public assets and performs public tasks.”