Translation: Voxeurop

Photo: David W. Cerny / Reuters / Forum 2023-12-11

Translation: Voxeurop

Photo: David W. Cerny / Reuters / Forum 2023-12-11

EPH, the Czech Republic’s largest company, is far from being the European leader in decarbonisation it likes to portrait itself. According to a recent investigation by Deník Referendum, the company, owned by Czech coal baron Daniel Křetínský, uses ‘creative’ accounting of its greenhouse gas emissions to sweeten the picture of its real impact on the climate.

In the introduction to one of the few interviews that Daniel Křetínský, the second richest person in the Czech Republic, gave to the Czech media this summer, Forbes magazine asked the rhetorical question: “Who is the person who is being portrayed in some media as a coal baron and one of the biggest air polluters, even though it is not true?” The short answer could be that Daniel Křetínský is a coal baron and one of the world’s biggest polluters, although he tries to pretend it isn’t true. But how is it that Křetínský and his company, Energetický a průmyslový holding (EPH), manage to keep up the appearance?

The company’s carefully cultivated image is linked to the carbon accounting it uses to present itself to the public. EPH claims to be a “leader in European decarbonisation”. But according to the data we have compiled, even a conservative view of its emissions places it among the three dirtiest companies in the European Union. And there are no relevant facts to support the claim of being a “European decarbonisation leader”.

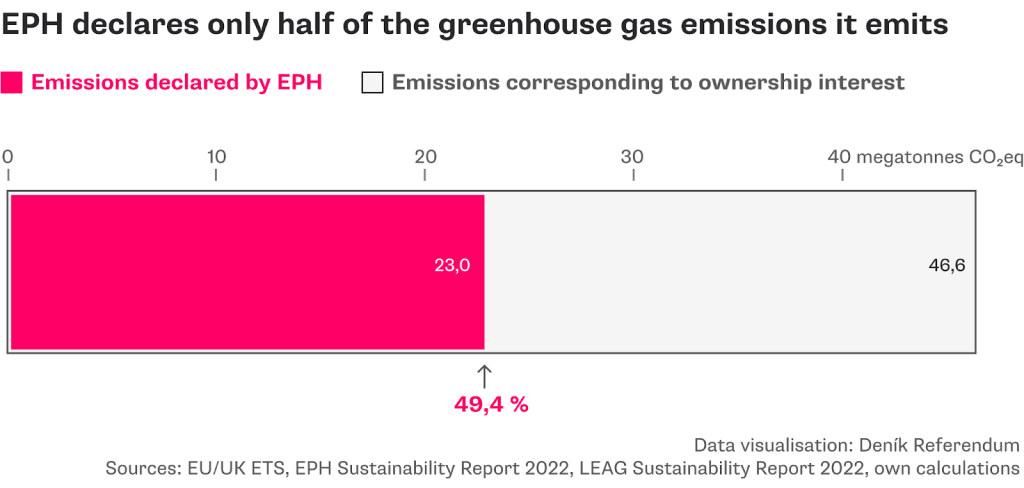

In fact, EPH reports less than half of its emissions in its carbon accounting, even when we use a conservative methodology. Moreover, our analysis shows that the power plants in EPH’s portfolio are decarbonising more slowly than the rest of the EU power sector.

EPH is one of Europe’s three top polluters

Of course, it is important for companies to transparently report accurate information about their carbon footprint for a number of reasons. It is essential because it affects a company’s public image. It affects its public image, which can also attract or deter investors.

Investor attractiveness is, after all, one of the main reasons why companies keep climate accounts. On the basis of climate accounting, they often commission an environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating. This determines the extent to which a company is exposed to the risk that, for example, climate change or the decarbonisation of the economy could jeopardise its financial performance.

However, it is not only the private sector that is making decisions based on climate accounting; governments and public institutions are also increasingly taking it into account. The European Central Bank, for example, announced last year that it would gradually decarbonise its corporate bond portfolio, although it eventually backtracked from its original plans this year.

But allocating responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions in the energy sector is not easy. Apart from the question of whether emissions should be attributed to the mining company, the fuel transporter, the power plant owner, the consumer or the whole economic system, there is also the question of how to divide responsibility among the various shareholders of power plants. Or, for example, between those who own the power stations and those who operate them.

There are several ways of allocating responsibility for emissions. For now, it will be sufficient to say that conventional carbon accounting approaches allocate emissions either by ownership or by who controls the company.

But it can also be useful to look at, for example, the total emissions from all the activities in which the company is involved, as we may be interested in facts that conventional carbon accounting methods do not take into account. Each of these methods has its pros and cons, which we will come back to.

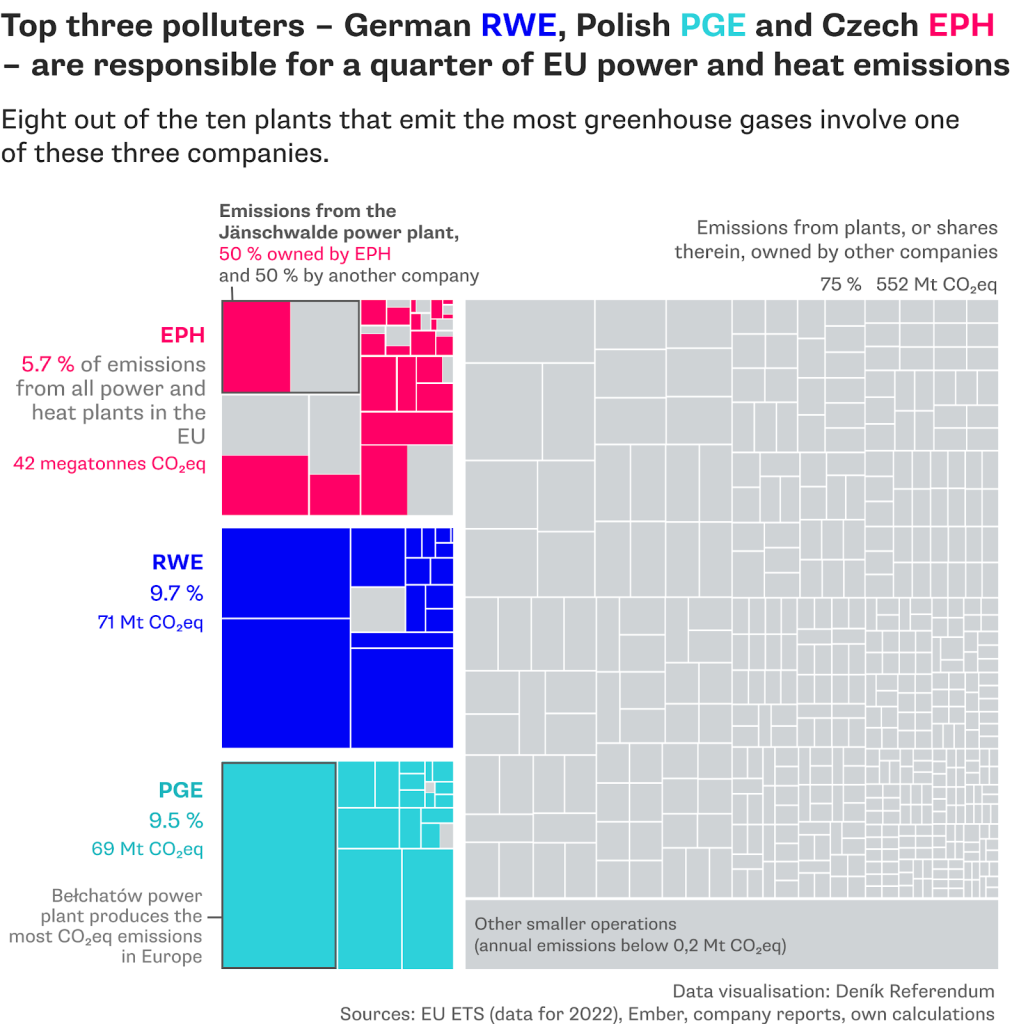

The bottom line is that all of them place EPH among the top three CO2 emitters in the European Union – along with Germany’s RWE and Poland’s PGE. The exact ranking within the top three may vary depending on the method used.

An analysis of data from the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) shows that EPH, together with German listed RWE and Polish semi-public PGE, is responsible for a quarter of emissions from the energy sector in the entire European Union. Here we only attribute emissions according to ownership, which is the most favourable option for the three largest polluters. EPH alone is responsible for about 6% of the total emissions of the European energy sector, again using a favourable approach.

As the chart shows, the big three’s significant share is due to the fact that each of them owns a disproportionate number of the dirtiest plants. Eight of the ten dirtiest power stations in the European Union are owned by these companies. All eight burn lignite.

EPH co-owns three of the ten dirtiest plants. And a fourth is close behind in eleventh place. These are the German lignite power plants of the Lausitz-based LEAG group, which EPH owns together with the Czech investment group PPF. Together, these plants emitted almost 56 megatonnes of CO2 last year, or 7.6% of the emissions of the entire energy sector in the European Union.

Why so much? On the one hand, they are really huge plants, so logically they produce more emissions. But they are also very inefficient. Lusatian power plants emit about four times as many grams of greenhouse gases per kilowatt-hour of energy as the average European power plant.

The emission intensity of the Lusatian power plants is also about twice as high as the sources disclosed by EPH in its sustainability report. They are so dirty that their carbon intensity even exceeds the upper limit for coal in the modelling tables of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

EPH reports less than half of its emissions

And the Lusatian power plants simply do not appear in the total list of EPH’s emissions presented in the report. The company discloses 23 megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions. However, our analysis shows that even a conservative approach would attribute around 47 megatonnes of greenhouse gases to the company in 2022. To put it bluntly, EPH declares less than half of its emissions.

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol standard, one of the most widely used carbon accounting methodologies for companies, offers two basic ways to account for emissions. A company can account for emissions based on its ownership stake, or based on whether it exercises financial or operational control over the asset.

The first approach is fairly straightforward, but EPH has not chosen it. Under the second approach, the company records all emissions from the operations it controls in its carbon accounts. In doing so, it must also assess the cases where it exercises control jointly with other entities.

If the calculation is based on financial control and is jointly exercised by partner companies, they should add the emissions for these assets according to their respective shares. However, EPH has not chosen this method either. It calculates its emissions using the operational control method, which may involve contractual arrangements between the business partners.

LEAG’s highly polluting Lusatian power plants are one such joint venture. EPH states in its 2022 Sustainability Report that it exercises joint control over the company, i.e. it does not make decisions alone, but together with another shareholder.

Therefore, if it chose the financial control method, it would have to report its share of emissions. However, EPH states that it reports its data according to the operational control method, i.e. based on whether it can make decisions on the company’s operations.

For example, EPH counts negligible emissions from the Czech cogeneration plant Plzeňská teplárenská, where it has management control, although it owns barely a quarter of the total. On the other hand, EPH does not include in its total emissions the Greenho

For example, EPH counts negligible emissions from the Czech cogeneration plant Plzeňská teplárenská, of which it has management control, although it owns barely a quarter of the total. On the other hand, EPH does not include in its total emissions the greenhouse gases emitted by LEAG, Slovenské elektrárne and the Italian gas-fired power plant Scandale, over which it claims to have neither financial nor operational control.

The individual companies therefore keep their carbon accounts separate. They report their own emissions, but EPH itself does not account for them at all. This is clearly a deliberate practice.

EPH seems to be aware of this. Although the 2021 report does not include the emissions of the Lusatian power plants in the total, we can at least still find them in the appendix “Main LEAG figures” (on page 315). In the latest report, however, even this reference has been dropped.

“It certainly puts the company in a better light,” comments Lia Wagner, an analyst at Urgewald, a German organisation that specialises in researching fossil fuel companies and then providing data on them to financial institutions. The effort to distance itself from LEAG is confirmed by the fact that, since this summer, EPH no longer even lists LEAG as one of the companies in its portfolio on its website.

The resulting picture of EPH’s emissions is therefore the result of the choice of carbon accounting method. The operational method used assigns responsibility for emissions to the decision maker in the “medium term”. However, this is extremely misleading, particularly in the case of the Lausitz power plants, where the long-term horizon is crucial from a climate perspective.

LEAG and MIBRAG, which is wholly owned by EPH, are the only energy producers in Germany planning to operate lignite-fired power plants beyond 2030. “LEAG and the virtually emission-free Slovenské elektrarne are not included in EPH’s sustainability report because this is in line with international methodology,” EPH spokesman Daniel Častvaj confirmed when asked by Deník Referendum why EPH does not declare the substantial amount of emissions for which it is actually responsible.

EPH should not claim it is not responsible for LEAG’s emissions

It is difficult to judge from public sources whether EPH’s carbon accounting itself is correct, at least from a formal point of view, as we do not have access to contracts between shareholders, for example. However, the fact that the company presents itself to the public on the basis of these figures gives the impression of a deliberate misrepresentation.

“Even if it is not against the law, I think the company deserves criticism for this. It definitely makes them look better than they are,” Lia Wagner from Urgewald told Deník Referendum.

The company’s external communication gives the clear impression that EPH has in fact been in a leading role in the joint venture for a long time and is therefore responsible for LEAG’s operations. This is confirmed by the statement of the other shareholder in the PPF Group in this year’s half-yearly report on the company’s financial performance.

In it, PPF says: “As of 30 June 2023, the Group’s total shareholding in LEAG represented a 50% share in economic rights (since the acquisition in 2016, the Group’s legal effective ownership is zero, it only has joint control over LEAG through the contractual arrangements with the joint venture partner).” PPF therefore considers itself to be a financial investor only.

Finally, a look at the entry in the Commercial Register of LEAG Holding, a.s., through which EPH and PPF jointly own the majority of the shares, shows that all members of the Board of Directors and two of the three members of the Supervisory Board are EPH employees. Therefore, it is debatable as to which exact share of the issue should be counted as EPH’s own. However, a zero share does not reflect reality.

Křetínský shifts its dirtiest resources to a new company

The fact that Křetínský itself is aware of this is shown by another manoeuvre it has launched this year. So far, we have analysed the latest available emissions data for 2022.

In October this year, however, PPF sold 20% of its stake in LEAG for one euro to EP Energy Transition, a new sister company of EPH with the same ownership structure. The two companies now together own a full 70% of LEAG, i.e. a controlling stake. The transaction was coincidentally reported by the business daily E15, co-owned by Daniel Křetínský.

EPH plans to gradually transfer its remaining 50% stake in LEAG to EP Energy Transitions, and eventually also its lignite-fired power plant in Schkopau, Saxony-Anhalt. In addition to the power plants, EPH will also transfer its German open cast lignite mines to the new structure, making EPH the third largest coal mining company in the European Union in terms of shareholdings. Once again alongside Germany’s RWE and Poland’s PGE.

In this way, a parallel corporate structure will enable EPH to formally divest itself of its lignite resources, which it does not intend to cease mining until after 2030, the year to which the German government has committed itself in the coalition agreement. Formally, EPH will be able to pretend that it will abandon coal-fired power generation itself by 2030.

“The fact that two legal entities have the same owners does not mean that one is responsible for the other,” wrote Daniel Častvaj, spokesman for EPH, in a response to Deník Referendum on the decision to separate lignite resources. This indirectly confirms the usefulness of the whole operation. Without the creation of this structure, EPH itself would have had to consolidate the company and take responsibility for it.

The German organisation Urgewald, mentioned above, is also critical of the new structure. Among other things, it is concerned that EP Energy Transition will not have sufficient resources to recultivate the landscape affected by mining.

Karsten Smid, a researcher at Greenpeace’s German headquarters in Hamburg, expresses similar concerns. “Recultivation will require an investment of around three to ten billion euros. However, it is currently unclear whether the company has these funds,” he told Deník Referendum. However, EPH spokesman Daniel Častvaj told Deník Referendum that “mining companies make provisions for recultivation in accordance with the relevant laws and regulations”.

But recultivation is not the only issue. Even the formal separation of the dirtiest energy sources from the rest of the company raises serious questions. “EPH needs bond financing. But banks and other financial institutions are already counting on the fact that coal has no future. The new accounting structure will help the company look relatively green and continue to attract financing,” says Smid.

The plan to create a framework for raising green finance is also mentioned by EPH in its sustainability report, alongside the claim that it will almost completely phase out coal-fired power generation by the end of 2025. It is therefore possible that the transfer of dirty resources is intended to help EPH meet the criteria for obtaining financing from, for example, green bonds. These have stricter climate impact requirements than conventional bonds.

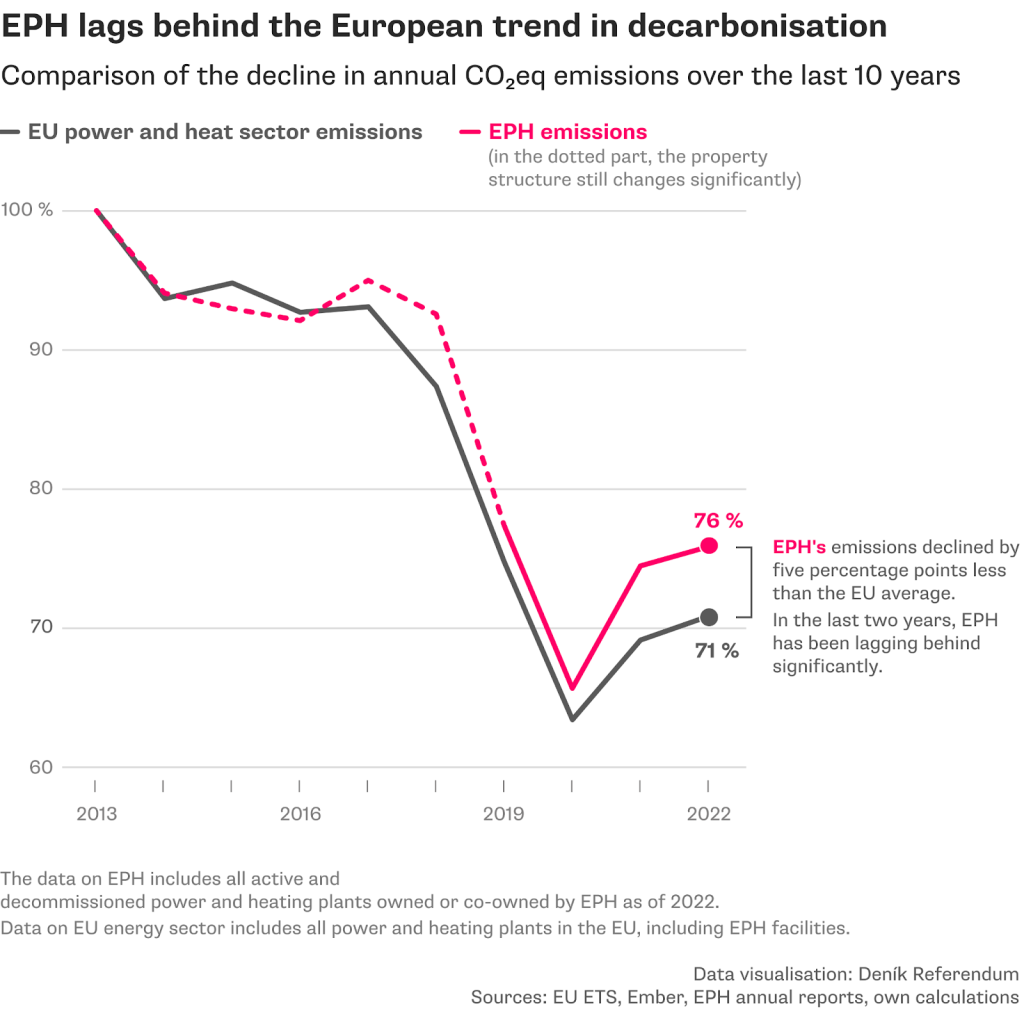

EPH power plants lag behind European trend in decarbonisation

“EPH is a European leader in decarbonisation and the transition from coal to clean energy,” EPH proclaimed in its presentation last year. Even today, the company sees itself as “a leader in the energy transition in Europe”. This claim was echoed, for example, by the then editor-in-chief of Křetínský’s media outlet Info.cz. But even in this case, the company’s self-portrayal is at odds with reality.

We have analysed the data for all power and heating plants – active and retired – currently owned by EPH and compared it with the entire energy sector in the European Union over the last ten years. A review of the reduction in emissions compared to 2013 shows that the power plants in which EPH has an interest are following the European trend and have lagged behind in recent years.

The company was five percentage points worse off than the European power sector last year. We see a similar trend if we take the average of the first three years.

One might ask whether the analysis is biassed by the fact that we have included all the resources currently owned by the company, including those that were not part of the holding ten years ago. After all, EPH’s asset structure has changed beyond recognition over the past ten years.

However, the trend is confirmed even if we take 2019 as a baseline, since the power plant portfolio has not changed much since then until 2022. On the basis of the available data, it is therefore impossible to conclude that EPH is leading the decarbonisation of the European Union, as it claims to be.

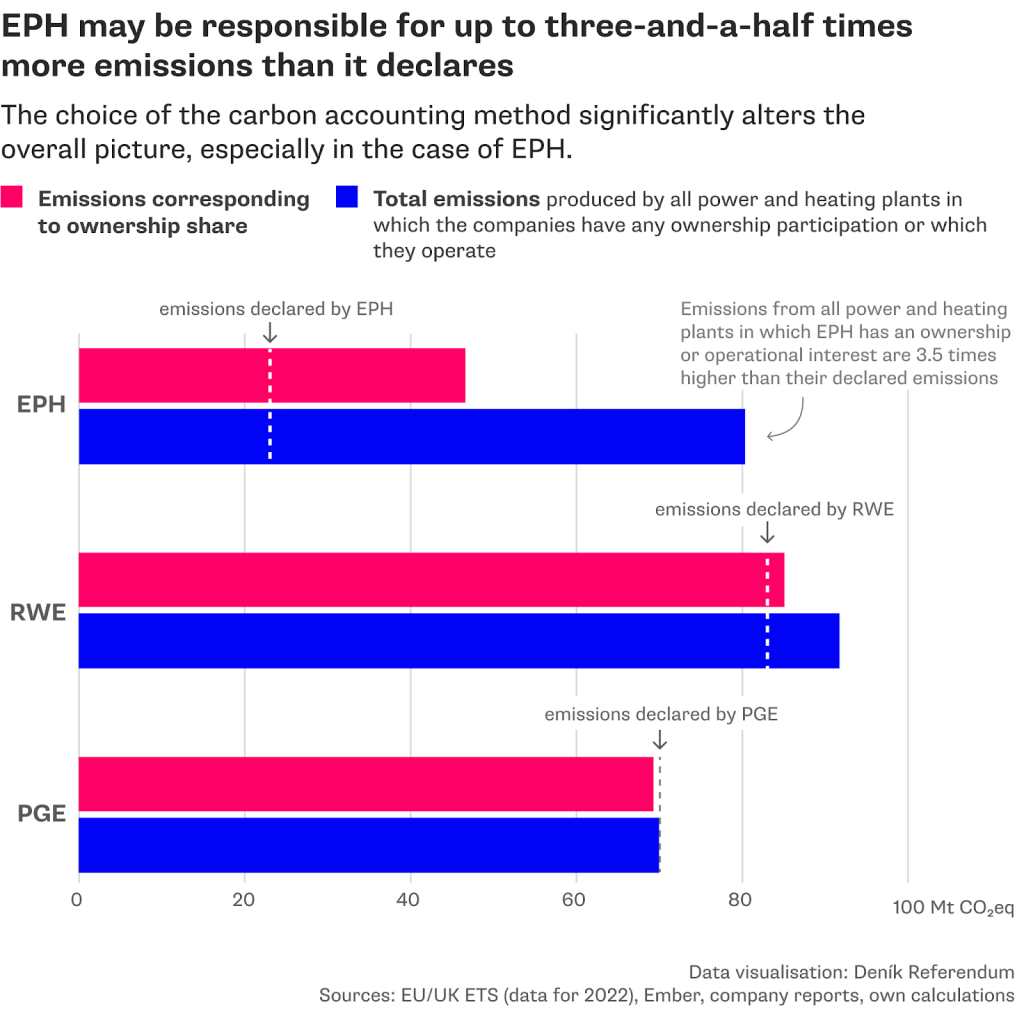

In the past, we have been lenient with the biggest polluters in our calculations. However, the share approach we have used so far does not take into account who actually makes the decisions about the operation of the plant, especially in the long term. This too is controversial, as we have seen.

However, can there be a justification for the obligation to disclose full emissions data for all operations in which companies or their owners are involved? Such a requirement may seem counterintuitive, as it would inevitably lead to double counting of identical emissions to multiple shareholders.

But even such an approach seems perfectly legitimate. If the stated aim of climate policy is to phase out greenhouse gas-emitting energy sources and redirect resources towards non-emitting technologies, the market, together with the public sector, should encourage investors and shareholders to avoid even partial ownership of carbon emitting sources.

This approach is quite common when we consider the distribution of responsibility for various other pathological behaviours or transgressions. Even when several perpetrators commit a crime together, each is held fully responsible. It is therefore appropriate to require that the full climate impact of all operations in which companies or shareholders are involved, either through ownership or operational control, be accounted for.

It is clear from the graph that the degree of responsibility for the Lusatian power plants that we attribute to EPH has a very significant impact on the company’s climate accounting. For both RWE and PGE, the reported emissions do not differ significantly from those attributed to them under the share or participation method. The example of EPH therefore illustrates how important it is to know the full climate impact of companies if we want to incentivise them to move rapidly away from fossil fuels.

At the European level, the role of carbon accounting is currently being debated. A new European directive sets out rules for so-called non-financial reporting. Large companies will have to report on the environmental and social impacts of their activities starting in 2024. The advantage is that companies will not only have to explain how climate change and decarbonisation could threaten their financial performance, but also how their business itself affects the environment and society.

However, the recently adopted version has moved away from mandatory reporting on emissions in particular, leaving it on a voluntary basis. Scientists have sharply criticised the European legislators for this.

Without accurate information it is impossible to make the right decisions, in both the public and private sectors. But better information on the true climate impact of companies is only one small piece of the puzzle.

Assessing the true climate impact of EPH also reveals a deeper problem with our current approach to transforming society to a zero-carbon economy. So far, governments have largely left the pace and nature of the transformation to the private finance sector.

It is about setting rules. The basic starting point would seem to be for the European Union and its member states to establish rules that make ‘creative’ carbon accounting, as practised by EPH, impossible, and to eliminate the possibility of gaining an unfair advantage by deliberately creating parallel companies into which dirty operations are transferred so that the original company can compete for green subsidies and investment.

Big polluters like EPH routinely tout their positive environmental, social and governance ratings and attract financial investors to buy their bonds and finance their operations, even though the reality of their climate impacts is fundamentally different. The example of EPH shows that the current approach simply does not lead to a redirection of resources away from dirty industries towards greener forms of business. Governments themselves need to take a much more active role in determining where public and private resources are channelled.

Published in partnership with Voxeurop. The original article was published in Slovak in Deník Referendum

Daniel Kotecký is an investigative and data journalist at Deník Referendum. He graduated with a BA in European Politics from King’s College London and an MA in Political Theory from the University of Oxford. In the past he collaborated on the analysis of debt traps at the Center for Social Issues – SPOT. Twitter: @danielkotecky