Photos by Antonina Chycka 2024-02-06

Photos by Antonina Chycka 2024-02-06

The Baltic coastal fishers are going extinct. Entangled in the net with possible culprits are some of the expected ones: Brussels’ regulators, industrial trawlers, and environmental pollution, as well as the unexpected: conservationists, gray seals, and a parasitic roundworm.

Antoni Struck looks like a casting director’s idea of a fisherman. He also looks very much unlike those members of the Association of Polish Coastal Fishermen who tend to wear a fancy watch and drive a nice set of wheels. In fact, when the Association meets in the local town hall, some of the attendees look less like fishermen and more like businessmen who happen to have a stake in fisheries. Struck sits through these meetings in his unbranded workwear and sturdy boots, arms folded stubbornly across his chest, looking as though he has just stepped off his boat and is in no mood to be pushed around. “A man can put up with a lot of things,” he is fond of saying. “But he needs to know just one thing: what it is for.”

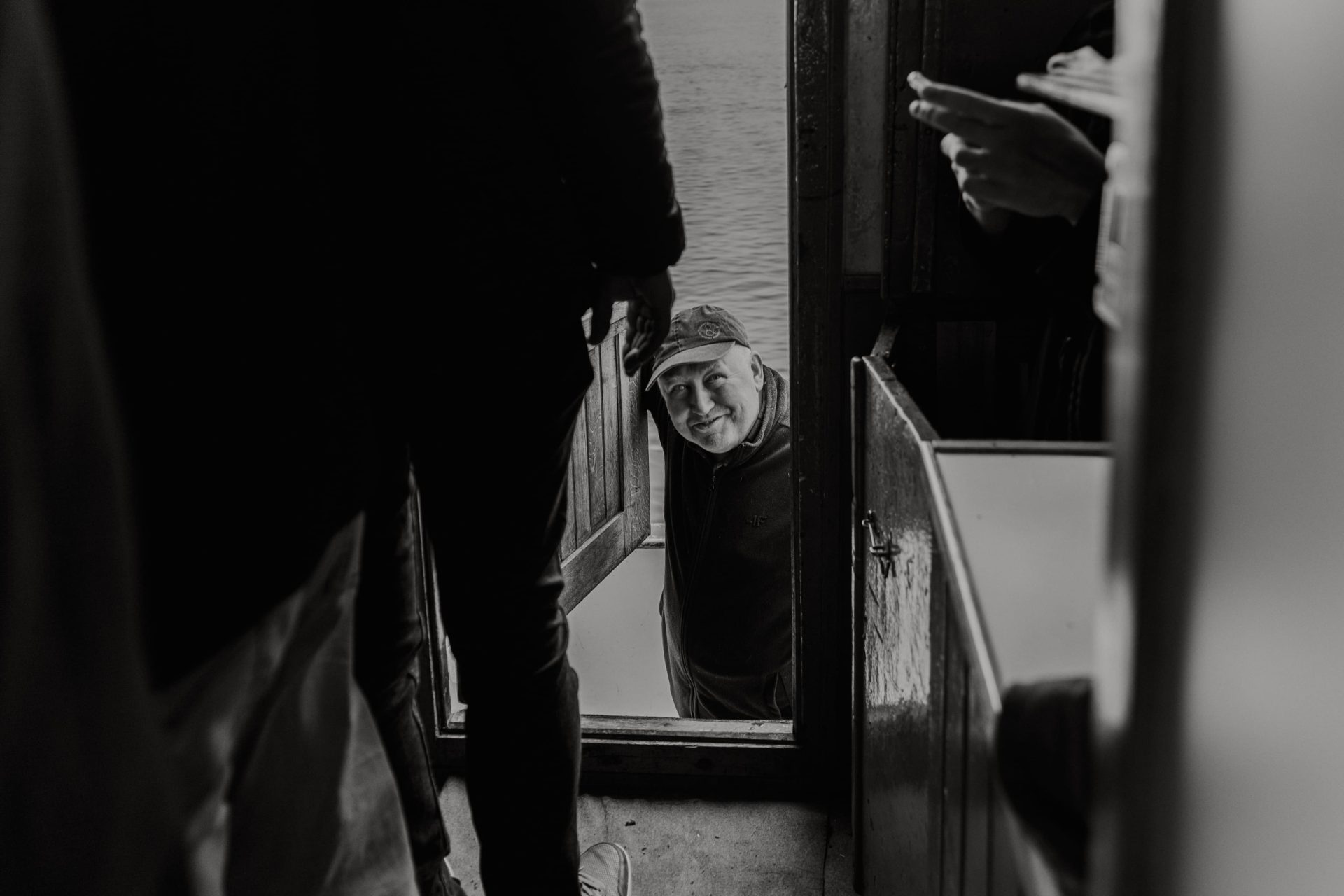

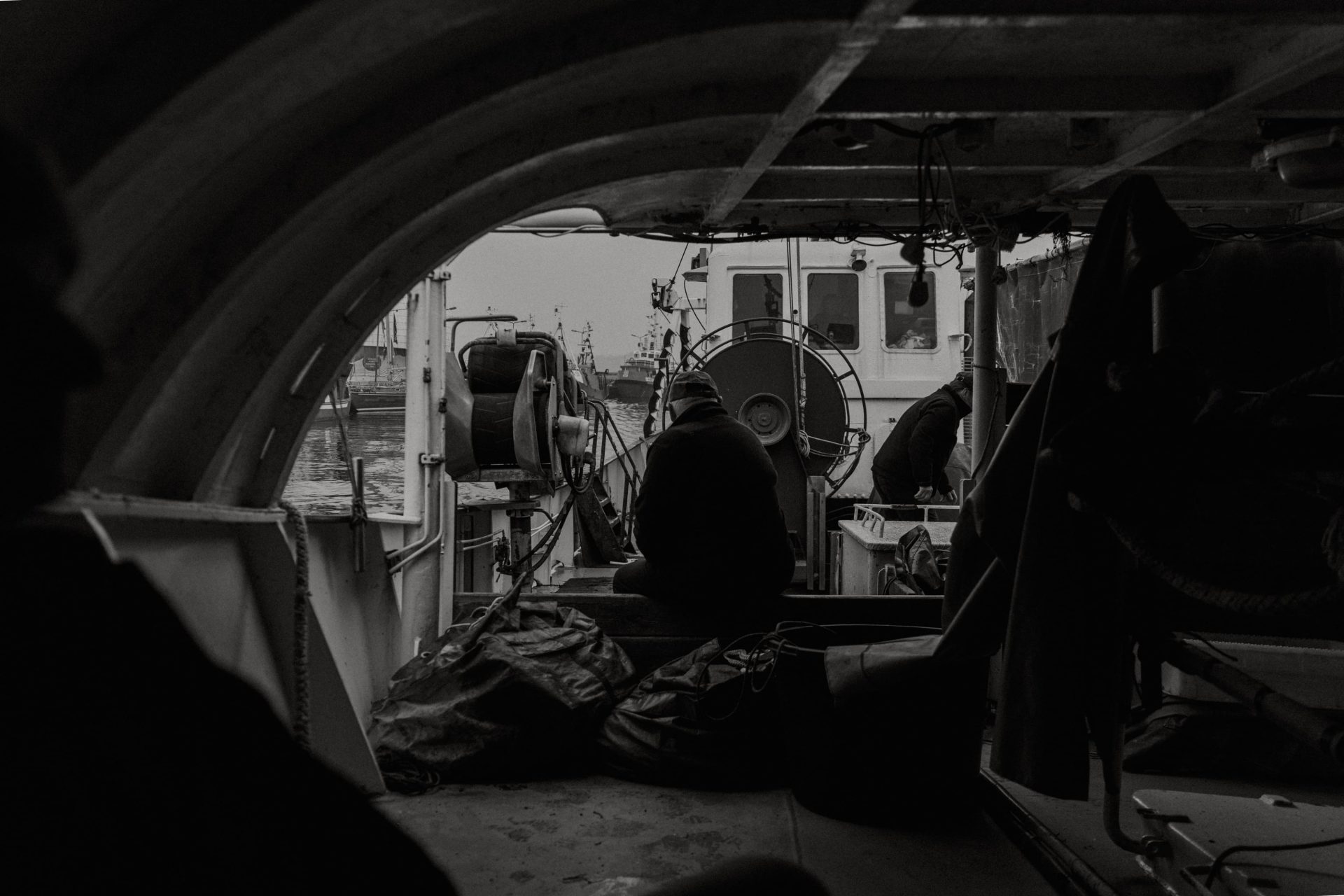

His boat is moored in the harbour in Kuznica, on Poland’s Baltic coast. Traditionally a fishing settlement, Kuznica is now better known as a tourist resort, its narrow, stone streets and quaint brick houses promoted as an attraction for the hundreds of thousands of Poles who holiday on the Hel peninsula every summer. On a foggy autumn morning, the tourists were long gone, the souvenir stands were folded away and the windows of the seafood restaurants were curtained. Struck boarded the swaying boat without breaking stride, as though the deck were an extension of the pier. The engine sputtered and the smell of diesel travelled over the water.

Struck steered the boat out to sea, one hand resting on the helm. The radio in the wheelhouse was tuned to a language that, to Polish ears, sounds a bit like Czech: the Kashubian dialect of this region, North Pomerania. A flat-screen monitor showed the vessel’s GPS co-ordinates, a rosary hung above the control panel, and postcards of the Holy Mary and Pope John Paul II adorned the window. According to the gospels, Christ’s earliest disciples were fishermen by trade. The fishermen of Struck’s generation, many of whom quit school for the sea, like to allude to their Biblical forebears when discussing their work.

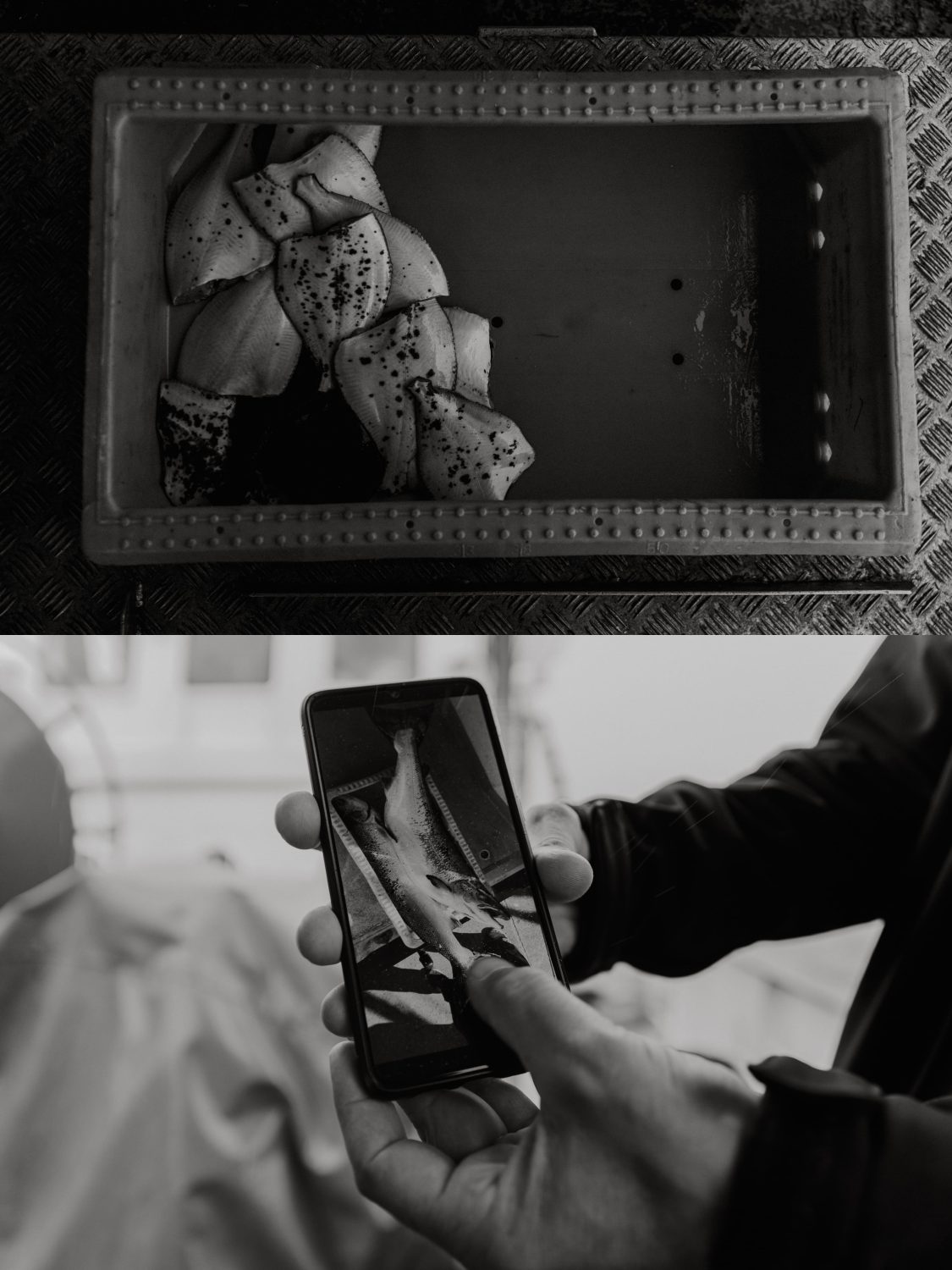

Beside the control panel sits an old knife, talisman from Struck’s first fishing expedition half a century ago, when he was 12 years old. Back then, the nets would come up heaving with fish, more than could fit onto the boat. In the wheelhouse today, the nets are pinpointed on a GPS monitor. Struck guides the boat towards them and draws up the ropes, working in controlled bursts. The nets are heavy with silt and largely devoid of fish. The day’s haul – two kilograms of flounder – will fit into a single carrier bag. “We’re going to be covered in fish today,” Struck mutters sarcastically. With flounder from industrial trawlers flooding the market, Struck’s catch will be worth less than a euro. Meanwhile, the diesel for this trip alone has cost Struck more than 100 euros.

A symbol of the early church, fish featured heavily in the miracles described in the gospels. In the best known of these, Christ used two fish to feed thousands of followers. Struck’s ambitions today are relatively modest. “All I want is to be able to support myself from my fishing, from my work, like in the old days.” His sons have no intention of following in his footsteps. One works as a trucker, the other found a job in Germany, and the third son has been flitting between casual gigs, looking for something stable. Lacking a miracle, Struck will be the last man in his family to work as a coastal fisherman, in a job that sustained both his father and grandfather.

For thousands of years, the Baltic has provided food and livelihoods for the people living on its shores. Now, the fish that support these communities are becoming scarce, and Poland’s coastal fishing fleet is shrinking. The small-scale owner-operators like Antoni Struck are being edged out, leaving the sea and its diminishing resources to bigger players. Within the coastal fleet, it is increasingly the large operators – the “businessmen” at the Association’s town hall meetings – that can afford to keep going to sea.

Far from the shoreline, on the high seas, the boats are even larger. The industrial-style trawlers operate in a different zone to the coastal fisheries, and they catch vastly more fish. The coastal fishermen accuse the large trawlers of stealing their livelihoods. “They come and fish everything, not caring whether it’s big or small,” Struck said. “They will destroy the sea and go elsewhere, and we will be left with desolation.”

The European Union is viewed as an accomplice to this crime because it has effectively banned the coastal vessels from catching some of the most valuable fish, cod and salmon. The bloc, citing scientific advisers, says stocks cannot recover without tough quotas. The coastal vessels have been squeezed hardest by the quotas because they relied overwhelmingly on the stocks that are most under pressure. The industrial trawlers have weathered the restrictions better because they do not depend on cod and salmon. Along with flounder, they also catch herring and sprat, relatively abundant species that typically end up as fishmeal, served to farmed animals.

The Baltic’s cod fisheries used to punch above their weight. In the mid 1980s, a time of plenty, roughly one in five cod catches were landed from this sea. Until recently, the fish caught by the Polish coastal fleet was reaching a Europe-wide market, distributed via brokers and wholesalers to England’s fish-and-chip shops and the dinner plates of French families.

Today, the coastal fisheries that depend on cod are limited to the same stock as the industrial trawlers. They can catch the flounder, herring and sprat if they want, but it is not economically viable. With the large trawlers serving the same market at scale, the coastal vessels simply cannot compete. The few fish they catch tend to get sold straight off the boat, to the locals and tourists visiting the harbour.

The coastal fishermen want tougher restrictions on industrial trawling, which they believe is depleting stocks in more ways than policymakers have grasped. “If the sea is to be saved, make everybody stop fishing, let’s say for two years,” Struck said, cleaning the silt from his nets. “Suspend both us and the big guys. Then we will see what happens.”

A moratorium on fishing might work if fishing were the only problem. However, over-exploitation does not adequately explain the dramatic changes – the scientific term is “regime shift” – underway in the Baltic eco-system. The collapse of the cod stock, for instance, is something of a mystery. Scientists discuss it in terms of hypotheses and coincidences rather than causal explanations. “In such a dynamic environment, there is no guarantee that conservation measures imposed today would not have unintended consequences,” said Dr Mariusz Zalewski of the National Marine Fisheries Research Institute of Poland, a state-funded think tank. “Even if we could somehow recreate the conditions from the past, that would not necessarily mean that cod, for example, becomes abundant again. Some other species could take this niché.” Zalewski said scientists cannot forecast what will happen in the Baltic as though it were a straightforward equation. “In such a situation, we cannot give a simple answer, we cannot say that two plus two is four. It can be four, it can be six.”

In recent decades, cod stocks around the world have collapsed, mostly as a result of overfishing.

In the Baltic however, it is hard to attribute the decline in the stock to any single cause. Periodic dips have, until recently, been corrected with temporary curbs on fishing. However, the Baltic cod population entered a seemingly irreversible decline over the past decade. The EU started reducing allowable catch limits in 2014 and has effectively prohibited targeted cod fishing since 2019 — it may now only be caught as “bycatch,” that is, caught inadvertently, in nets placed for other fish. However, the population shows no sign of recovery. The remaining fish also appear to be sick. They are smaller than they ought to be and reproduce at a much lower rate.

Overfishing has contributed to the decline, but scientists believe it is not the only cause. The cod’s access to food and its ability to reproduce are also thought to have been affected by a combination of warming seas, falling salinity levels and the process of eutrophication, whereby the nutrient-rich runoff from agricultural fertilizers collects in the sea, promoting algal blooms that reduce the supply of oxygen for other marine life. Similar factors have also been blamed for the decline of Baltic salmon, the other fish that was once a mainstay of the coastal fleet.

Who, then, is to blame for the decline of Poland’s coastal fisheries? The list of possible culprits includes Brussels, industrial trawlers and environmental degradation – those whom we might call the usual suspects. However, the line-up also includes some unusual suspects, including conservationists, the grey seal and a type of parasitic roundworm.

This is the tale of a scientific mystery, with as many shades of grey as the Baltic on a cloudy morning. At its heart are the coastal fishermen, trapped in a Catch-22 situation. A steady, decades-long decline in fish stocks is threatening their livelihoods, and the EU’s quotas are squeezing them further. The pain is meant to be offset by EU subsidies. To qualify for these subsidies however, the coastal fishermen must still be classed as “active”: they must fish for a minimum number of days every year. With no money to be made from selling fish, they end up fishing, in effect, for the subsidies.

“We fell out of the market,” said Henryk Indyk, a fisherman from the town of Hel. “Restaurants aren’t buying our fish, they only buy it from the west: cod and salmon from the Atlantic, flounder from the Netherlands.” Indyk said he was planning to “liquidate” his business. “For the last three years, we didn’t really fish anyway. We just went out to sea so that we could log enough ‘fishing days’.”

Antoni Struck helps cover the cost of his fishing expeditions under an EU environmental subsidy – he gets paid for logging sightings of sea-birds. Last year, he was contacted by the operator of a stall at a festival celebrating the region’s fishing heritage. He was asked if he could deliver 200 kg of flounder for the stall. Struck refused – there was no way he could procure that much fish locally. At the festival, visitors were served flounder from Portugal, sourced via the local supermarket.

“I don’t blame the coastal fishermen,” said Tadeusz Muza, a former councillor and current head of the Fisheries Museum in Hel, the biggest town on the peninsula in northern Poland that shares its name. “The truth is that a group of people owning industrial fishing vessels are making good money, and the rest are struggling to survive. So, they do what they have to do.”

Most of the fish eaten throughout human history has been caught near the shore. Coastal fleets to this day cater to the bulk of our fish consumption. They also provide most of the jobs in fisheries worldwide. In poorer parts of the world, coastal fishing is more than a source of food; it represents economic security for entire communities.

Industrial trawlers, on the other hand, employ a tiny workforce to deliver far greater volumes of fish. Compared to the small boat operated by Struck, the largest industrial trawlers on the Baltic can be floating factories. The biggest vessels in this category will be at least half the length of a football pitch, and capable of bringing in thousands of tonnes of fish on a single expedition. On board may be a crew of no more than a dozen, operating a highly mechanised production line that processes and packages the catch to varying degrees.

These two modes of fishing – the artisanal versus the industrial – are often in tension, according to Ray Hilborn, a professor at the School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences in the University of Washington and the author of several books on natural resource management and conservation. “Globally, most of the people who work in fisheries are working in small-scale fisheries,” he said. “But in an industrial capitalist world, all the incentives are to become more efficient.”

In theory, Hilborn said, both coastal fisheries and industrial trawlers could operate sustainably, and both could be implicated in over-fishing; neither mode was inherently better for the planet. “It all depends on how many fish they are catching,” he said. “There’s a common narrative that small-scale fisheries are benign for the environment and large-scale trawlers are destroying green eco-systems. There’s no evidence for that.”

Where sustainability was not a factor, the choice between coastal vessels and deep-sea trawlers boiled down to a question of function. “Is the purpose of fisheries to produce employment? Or is it to actually produce food efficiently?” asked Hilborn. “This is a big issue around the world.”

How much are we willing to pay for our fish, and for the survival of our coastal communities? The EU’s fisheries policy attempts to balance these questions. The bloc pays out subsidies to slow the decline of coastal fisheries, keeping unprofitable businesses alive in apparent recognition of their value to coastal communities. At the same time, Brussels rejects the coastal fisheries’ calls for tighter restrictions on the industrial trawlers – implicitly acknowledging that the larger vessels exploit the resource more effectively.

Fisheries provide a cheap and healthy source of protein for billions of people worldwide, and they have a lower carbon footprint than other forms of meat. Demand for fish is increasing as the global population grows, and so is alarm over the state of the marine environment. The Netflix film, Seaspiracy, was centred on a claim that fish populations worldwide were due to die out within 30 years because of over-exploitation and environmental degradation. In order to save the marine environment, some conservation activists have argued that humans should stop eating fish altogether.

Hilborn is among the scientists who have sought to debunk these claims. Over-fishing is a problem in some parts of the ocean but not in others. Data collected by Hilborn and his colleagues shows that the wealthier economies of Europe and North America have reversed some of the damage from over-fishing, and vital stocks are recovering. “Fisheries management is actually working in the places where it is practiced,” Hilborn said. He cautioned that data were lacking from poorer regions of the world such as Asia and Africa, and fish stocks there were believed to be under severe pressure.

Processed cod was once fuel for exploration and exploitation. Like slaves, sugar, cotton and tobacco, cod was an integral element in the nexus of trans-Atlantic trade linking the Americas, Africa and Europe. In its dried and salted form, the succulent, protein-rich fish could keep for long periods in warm climates. It was ideal rations for Basque and Viking seafarers and gradually became a commodity in its own right, something that could be traded with the inhabitants of newly discovered territories. Dried fish “gave shipping the range of the tropics,” writes Harold Innis, the Canadian theorist and mentor to the philosopher Marshall MacLuhan, in his 1940 classic, The Cod Fisheries: The History of an International Economy. Slavery further expanded the market. As Innis documented, vast quantities of cod from the rich waters off New England and Newfoundland were preserved and shipped south, as a cheap protein supplement for slaves producing tobacco and sugar.

The Baltic cod industry played a minor, though pivotal, role in this story. Back in the 15th century, the industry was monopolised by a sort of proto-European Union, the Hanseatic League. A medieval confederation of port cities serving German business interests, the League dominated maritime commerce in northern Europe and exerted huge influence over the region’s politics. In 1475, the League cut the English port of Bristol out of the trade in Icelandic cod. In a story told by Mark Kurlansky, the author of Cod: The Fish That Changed the World, Bristol merchants went in search of an alternative supply of cod and found it in North America, years before Christopher Columbus got there.

From salted and dried Portuguese bacalhau to the fish balls of Eastern Europe to Greek taramasalata using its roe, cod has become an intrinsic part of European fare. In Poland, locally sourced cod has served as a dietary staple, particularly for the poor. During the communist era, which was marked by routine shortages of food items, Poles used to remark, “Jedzcie dorsze, gówno gorsze” – “eat cod; it’s better than eating shit”.

Baltic fisheries policy today is steered by some of the richest economies in the EU — Denmark, Germany, Sweden and Finland — as well as poorer members such as Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The sea is also bordered by Russia, whose share of the catch is governed by a treaty with the EU. The decline of the sea’s fish stocks is all the more puzzling, given that key players are co-operating on regulatory matters.

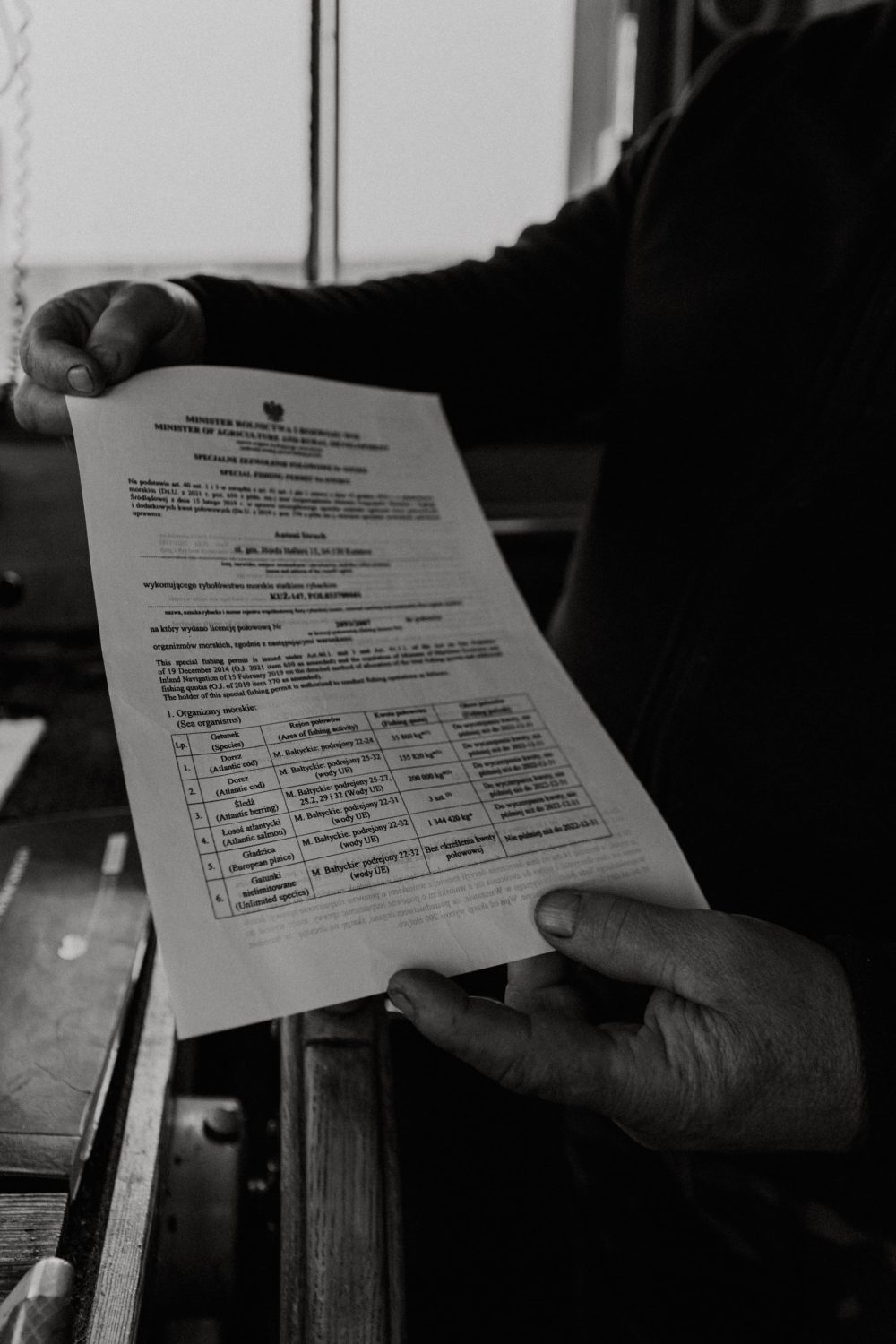

Under current Polish rules, Struck’s boat may operate in a zone that is sometimes as narrow as 3 miles — and never wider than 6 miles — from the coastline. The catch must moreover adhere to strict limits for the cod and salmon that were once so abundant. His current permit states he may catch no more than three salmon in a year. Moreover, the permit says, this salmon must be “bycatch” – just like the fisheries’ erstwhile staple, Baltic cod. “They are making us criminals in our sea,” Struck said.

“They”, in this case, is shorthand for the pen-pushers, blamed for managing the quotas for the coastal fisheries. These rules are, in fact, determined by the European Union’s Agriculture and Fisheries Council, or Agrifish, a body comprising the agriculture and fisheries ministers from the EU’s 27 member states. Every October, the members of Agrifish gather in a Luxembourg conference centre to agree the quotas for the coming year.

How much fish should each country catch? Agrifish decisions attempt to balance seemingly irreconcilable imperatives. A minister striding into the lobby of the conference centre carries the weight of expectations from the fishing sector back home – comprising the deep-sea trawlers, as well as vessels of various sizes that make up the coastal fleet. As these elements of the sector view each other as rivals, they make conflicting demands of their own governments.

Under the domed chamber that hosts the Agrifish plenary session, the minister will be confronted by yet more demands – from EU counterparts making representations on behalf of their respective fishing sectors. Complicating matters further will be the warnings from conservation bodies, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, and the guidance from scientists, who will advise on the maximum sustainable yield – the highest number of fish that may be caught without depleting stocks further.

Traditionally, the scientific advice at Agrifish has been outweighed by political considerations, according to a Polish marine expert at an international environmental organisation who did not wish to be quoted by name. Recently though, the expert said, the politicians have begun paying more attention to scientists whose dire warnings are being confirmed by events. The ministers at Agrifish will each seek to secure the highest possible quotas for the fishermen back home. If they leave with a bad deal, jobs and votes will be at stake. For the coastal fishermen however, there are few good deals left.

The interests of the EU and the Polish fishermen were not always opposed. Back when Poland was applying to join the bloc, the coastal fishing industry was cast as a sustainable alternative to the industrial trawlers that were being blamed for depleting fish stocks. Developing the coastal industry would, it was argued, satisfy EU accession criteria by protecting livelihoods and the marine environment.

In 2001, Poland’s National Marine Fisheries Research Institute presented the case in detail. Professor Zygmunt Polanski, an ichthyologist from the Institute, estimated that the coastal fishermen caught one-eighth of the fish brought in by the big trawlers and at half the cost, and with a value per kilogram that was two-and-a-half times higher than that caught by the trawlers. Polanski wrote that the coastal fisheries also helped the local economy, by attracting tourism and generating three to four times as many jobs as the big trawlers. The fishermen themselves had shown how they could serve as an early warning system for the marine environment, having reported a major sewage discharge into the Baltic.

Both the Polish authorities and the European Union say they have tried their best to preserve coastal fisheries. Indeed, in the 19 years since Poland became an EU member, the coastal fishermen have received a range of subsidies to help keep them afloat, including recent grants to offset the impact of the Covid pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Over the same period however, the EU has been tightening limits on the size of the catch. In an e-mailed comment for this story, the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, said its fisheries policy aimed for “environmental, social and economic sustainability”. Daniela Stoycheva, a press officer for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries at the Commission, said boats less than 12 metres long – of the type associated with coastal fisheries – made up more than two-thirds of the fishing vessels operating in the European Union. She said member states were allowed to grant “preferential access to coastal waters” and “preferential rates of support” to these vessels, in recognition of their “important socio-economic role in many coastal communities.”

However, the data from Poland tell a different story. In 2003, the coastal fishing fleet – boats 12m or less in length – was made up of 991 vessels. By 2022, that number was down to 697, according to the registry of fishing vessels maintained by Poland’s central statistical office. In other words, almost one in three coastal fishing vessels have quit the sea in the last 20 years without being replaced. These figures moreover mask the scale of the decline, as most of the remaining vessels are surviving on subsidies. The dwindling stocks, coupled with restrictive quotas, mean they simply cannot catch enough fish to remain viable. And so they become fishing boats in name only, going to sea so that they can claim their subsidies.

Coastal fishermen corroborated the prevalence of this practice. Few agreed to be quoted by name however, out of concern for their reputations. Typical expeditions, they said, would set off just before midnight, so that the boat’s paperwork could show that it had been at sea for two days. When asked about the practice, the European Commission said it was “not aware of the cited issues”. In an e-mailed response, a spokesperson asked for “concrete information and data” to support reports that fishermen were going to sea for subsidies alone.

A fisherman from a small town to the west of the Hel peninsula said that he had been going to sea purely so that his boat remained “active” and eligible for EU subsidies. “How am I protecting nature when I’m pointlessly burning hundreds of litres of diesel?” he said. The fisherman said he supplemented his income by selling cod to tourists at the local port. The cod was presented as “local catch” but had, in fact, been bought at a supermarket, which had imported it. The subterfuge prompted an awkward encounter with a controller, who was visiting the port to check if the local vessels were adhering to the catch limits. Spotting the cod for sale, the controller warned the fisherman that his catch was illegal. The fisherman had to placate the controller by revealing that his “local catch” had been sourced from the local supermarket.

Along with subsidies to keep the coastal fishermen afloat, the EU has been assisting those looking for a way out. Grants have been awarded to boat-owners who want to liquidate their fishing business and start afresh in sectors such as tourism. A boat-owner from a town near the Hel peninsula, speaking on condition of anonymity, said he had received a quarter of a million euros in EU funding to launch a “pesca-tourism” scheme – a model that aims to incorporate tourism into the coastal fisheries. The fisherman said he had been sent on a fact-finding trip to France’s Atlantic coast, where pesca-tourism entrepreneurs had been taking tourists for fishing expeditions. When the fisherman proposed a similar scheme back home in Poland, he was barred on the grounds that his type of boat could not legally accommodate casual visitors. “I’ve never had a single tourist on board,” he said. Dissuaded from his pesca-tourism proposal, he used the transitional funds to open a guesthouse on the coast.

Henry Indyk, the fisherman from the town of Hel, similarly branched into the hospitality business, using an EU grant to open a small guest-house. “Pretty much anyone who wanted could get some funds for transitioning, provided they also invested their own money,” he said. The guest-house has provided a lifeline as his boat racks up expenses, with room rents paying for much of the vessel’s upkeep. Indyk’s two brothers are his business partners, and his wife is the manager, keeping track of spending. “Last month, she was happy,” Indyk said. “Each of us brothers spent only 500 euros on maintaining the boat.”

The Indyk brothers operate one of the larger vessels in the coastal fleet. Officially, their 17-metre long boat is not classed as a coastal vessel; it is five metres too long. But the boat is typical of coastal fisheries in other respects. It is family-owned and operated, and looking for a new owner. Indyk’s only child, a daughter, left Hel for a job in Gdansk, Poland’s biggest port. His nephew migrated to France to work in a shipyard. Having fished since he was a boy, Indyk believes these are his last days at sea. “I’d rather leave all this to someone,” he said. “But it is what it is.”

Indyk lives in a traditional, gabled cottage in a central neighbourhood of Hel, a few streets away from the town’s top tourist attraction, a sanctuary for grey seals. For many years now, he has been an unofficial spokesperson for the coastal fisheries, and his home, brimming with files and legal documents, serves as an archive of the industry’s traditions and travails. He is also a custodian of its anecdotes. One dramatic tale among many: a fisherman being swept out to sea, his leg entangled in the line from the net, was saved when a quick-thinking colleague slashed the rope with an axe.

Indyk looks back upon his own experience in the industry with deep frustration. He invested in his business, hoping to keep up with the latest EU guidelines and incentives, but frequently found himself out of pocket because of unforeseen developments. In 2019, the Indyk brothers embarked on an expensive upgrade of their boat. At the time, the EU was offering to refund half the cost of such projects. The brothers ploughed their savings into the re-fit, equipping the 60-year-old vessel with the latest electronics. In the following year, the Covid pandemic brought the coastal fisheries to a standstill. This time, the EU offered a subsidy to offset the coastal fishermen’s loss of income. Indyk’s vessel however was deemed ineligible for support. Having spent the previous year undergoing refurbishment, it had not passed enough days at sea to meet the criteria for an active vessel. Indyk said he lost out on 60,000 euros. Others, he said, had failed to meet the threshold for the Covid grant by no more than a day or two.

A Polish government official defended the criteria for determining who was eligible for the Covid subsidy. “The aim is to limit payments to entities that don’t fish,” said Dariusz Maminski, a press officer from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, which oversees the coastal fisheries.

This was not the first time the Indyk brothers have ended up questioning whether it was worth upgrading their boat. Fifteen years ago, they spent 50,000 euros on a new set of nets, after the old nets were deemed a threat to the harbour porpoise, a type of small aquatic mammal. Having replaced the nets, they realised that the expense was not strictly necessary: the old nets could have been fitted with a “pinger”, an electronic device that emits an acoustic signal to repel porpoises.

Traditionally, the few thousand fishermen of the Hel peninsula formed a tight-knit community. Everyone knew everyone else, practically on first-name terms. These relationships have been tested by the loss of traditional livelihoods. The partial replacement for those livelihoods, a subsidy system, is seen as inadequate and unfair, seemingly rewarding those who bend the rules while punishing compliance. The implementation of the system has left the fishermen distrustful of Brussels, their own government, and each other.

Their grievances are filtered through a profusion of associations. Meetings are filled with gossip over who took more than their share of subsidies, and who is not even a true fisherman. Stories abound of subsidies fraud, involving small boats that have been registered as fishing vessels by outsiders, purely for the purpose of claiming EU funds. “Last time I checked, there were over 50 associations,” said Antoni Struck. “All of it just made people quarrel. I don’t feel as if my interests are represented at all.”

In the summer of 2022, the coastal fishermen trooped into the town hall in Jastarnia, a resort on the Hel peninsula, for a meeting with a regional representative of Law and Justice, the national-conservative party that led the government in Warsaw. The surrounding electoral districts tend to be tightly contested. In the parliamentary elections last October, the opposition scraped a narrow victory in the province. Middle-class voters and city-dwellers tend to back the liberal, centre-right opposition, while working class communities – such as the coastal fishermen – tend to be stalwarts for Law and Justice. “I’d rather lose something with Law and Justice than gain it with the opposition,” muttered one of the older boat-owners at the Jastarnia town hall. The party, however, had nothing to offer its supporters. Its representative, a low-ranking official, could only promise the fishermen that she would transmit their complaints up the party hierarchy. As the meeting descended into rancour, one of the attendees, a card-carrying party member, spoke from the floor: “I’m in Law and Justice, and Law and Justice is in government. So what am I fighting against?”

If anything unites Poland’s coastal fishermen, it is the belief that industrial trawling must be curtailed in order for stocks to recover. There is no doubt that the sheer volume of fish caught by the industrial vessels dwarfs the amount caught by the coastal vessels. Facing pressure from coastal fishermen, some governments have taken drastic measures against the industrial trawlers. Last year, Sweden banned the largest vessels from fishing in its territorial waters. The move was fuelled by alarm at data from 2020, which contained the eye-catching revelation that a single industrial trawler in the waters off Stockholm county had caught 175 times more herring than the combined mass of all the herring caught by other units registered in the county.

The Polish authorities are now being urged to follow the Swedish example and push the industrial trawlers out of the country’s territorial waters – banning them, in effect, from operating within 12 nautical miles of the shore. The size of the current exclusion zone for the super-trawlers varies along the Polish coast. In some places, they can fish as close as three nautical miles to the shore, while elsewhere they must be at least six nautical miles away.

The Polish government agency responsible for fisheries argues that the current measures are sufficient. In an e-mailed response, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development said the size of the exclusion zone was determined with a view to protecting marine life, and reflected variations in the depth of the sea.

In the political battles triggered by declining fish stocks, the coastal fishermen have lined up against the industrial trawlers. However, the science is not entirely behind them. “I have not encountered data that would indicate that industrial fishery harms the eco-system, if it follows the regulations,” said Professor Jan Horbowy, the head of the Department of Fishery Resources at Poland’s National Marine Fisheries Research Institute.

The head of an industry body, representing Danish deep-sea trawler companies, said his organisation was open to discussing extending the exclusion zones where it made sense “from a biological or ecological perspective”. Esben Sverdrup-Jensen, the CEO of the Danish Pelagic Producers Organisation, said however that there was no basis for a blanket ban on large vessels fishing within 12 nautical miles of the coast. “There is a general scientific consensus that the situation [in the Baltic Sea] is caused by changes in the eco-system, and that we do not yet fully understand what has happened, and why,” he said, in an e-mailed statement.

As restrictions on fisheries have failed to prompt a recovery in Baltic fish stocks, scientists have been considering alternative explanations for the decline. The Baltic sea owes its form to plate tectonics and millenia of climate change; to the retreat of the glaciers that once covered Europe and the rise of the landmass relieved of their weight. The sea is relatively shallow, on average around 50 metres deep. Scientists believe this has made it more susceptible to the impact of our current, accelerated form of climate change: it is warming faster than larger bodies of water. The Baltic is also partially enclosed, giving it some of the qualities of a big lake. Connected to the North Sea by a narrow sound, it is brackish rather than saline. The run-off from agricultural fertilisers has pooled in its waters, leading to eutrophication. Pollution from other industries, including shipping, has also been accumulating in the sea.

Moreover, the cod seems to have become the inadvertent victim of a conservation success story. By his desk at his house in Hel, a few streets away from sanctuary for grey seals, Henryk Indyk threw a treat to his dog, Bronek, and pulled a folder of historical maps off the shelf. “Now this really will make me look like a crazy person,” he said. He pointed at a map showing the prevalence of a parasite afflicting the cod population in the Baltic. The liver worm, contracaecum osculatum, is known to weaken the fish and hurt their ability to breed. Over the last decade, the parasite has colonised the cod stocks in the Baltic. More than 90 per cent of the cod in the sea are believed to be infected, up from 11% in 2011 and 2.6 per cent in the late 1980, according to figures from the National Marine Fisheries Institute.

The liver worm also affects cod in other parts of the world. However, populations have thrived despite the parasite. Among Baltic cod, the worm has spread at remarkable speed. The steep rise in infection rates has had “negative consequences” for the cod, said Professor Magdalena Podolska, a specialist in parasites at the Institute.

The rapid spread of the liver worm coincides with the comeback of the Baltic grey seal, a once-endangered species whose population has grown over the last decade, thanks to a conservation drive. Scientists believe there is a clear link between the decline in cod stocks and the rise in grey seal numbers. The mature worms reside in the guts of the grey seal. The eggs produced by these worms are expelled through the seal’s faeces, and end up being consumed by marine invertebrates. As these organisms become prey for fish, the parasite works its way back up the food chain, gradually reaching the cod. When the cod ends up in the guts of its natural predator, the grey seal, the worms find an environment where they can reproduce, and the life cycle starts anew.

“During the last 10 years, we have documented that almost all the cod are infected and sometimes they can carry several hundred worms,” said Professor Kurt Buchmann, an authority on fish immunology and pathology at the University of Copenhagen. “Our DNA studies have confirmed that the liver worms in the cod come from the seals.”

Grey seals have lived in the Baltic for millenia. Valued by humans for their meat and fur, they were also viewed as competitors for the same resource: fish. In the nineteenth century, they were hunted intensively. As late as the 1920s, the Polish government was giving out bounties to seal hunters – the animal was seen as a threat to fish. In the twentieth century, grey seal numbers went into steep decline, coinciding with higher pollution levels and the growth of shipping and fisheries. By the 1970s, the regional population had dropped to some 3,000 animals.

That downward trend has been reversed over the last few decades by an international conservation effort. Today, there are estimated to be between 50-60,000 grey seals in the Baltic, and they are once again competing with the fishermen, sometimes over the same catch. The coastal fishermen have countless stories of seals raiding their nets. They speak of it as a clever predator, an animal that has figured out it is easier to “steal” than to hunt.

There are no reliable estimates for how much Baltic cod the seals are eating today. “The seals love to eat cod, but if no cod are present, they will clearly take other fish species,” said Professor Buchmann. A worst-case scenario suggests that the seals could be going through as much as 80,000 tonnes of cod a year. Meanwhile, the entire fishing fleet in the Baltic, from the coastal vessels to the industrial super-trawlers, is estimated to net 700,000 tonnes of fish a year, according to the Helsinki Commission, or Helcom, an inter-governmental organisation set up to protect the marine environment in the Baltic. The latest figure represents a big drop from the days of plenty towards the end of the twentieth century, when the annual catch often surpassed a million tonnes.

Having initially supported the conservation drive, Poland’s coastal fishermen turned against it when they realised their livelihoods were at risk. As an unofficial spokesperson for the coastal fisheries, Henryk Indyk was among the first to warn that the surge in the grey seal population was bad news. In 2017, he told a Polish parliamentary commission that the seals were “destroying” the stock, posing an existential threat to his trade.

Conservationists, however, stand by the campaign to save the grey seal. In a comment for this story, the World Wide Fund for Nature stated its official position, that current grey seal numbers still fell short of the indicators for a healthy population. “We do not question the scientifically proven fact that the grey seal population in the Baltic Sea is growing,” the statement said. “However, we are of the opinion that this species still requires protection in the Baltic region.”

The growth in grey seal numbers has nonetheless done unforeseen damage to Baltic cod stocks, according to marine experts. “If, purely hypothetically, we imagine that the entire seal population suddenly disappears from the Baltic Sea, the parasite will remain… for many years and continue to infect fish,” said Professor Magdalena Podolska from the National Marine Fisheries Research Institute of Poland. “I’m not against seals, I’m for eco-system sustainability. Let’s ask ourselves, should we protect one species at the expense of losing another?”

Privately however, many scientists concede that the Baltic cod is probably already doomed. And even if the population eventually rebounds, it will be too late for Poland’s coastal fisheries. Along with the boats and the sea-going tradition, handed down from fathers to sons, the industry is losing its infrastructure – the on-shore facilities for processing the catch and servicing the boats.

“What’s next? I don’t know what’s next,” said Antoni Struck, over a recent phone call from his home in Kuznica. “All these boats and nets lying idle, all that EU money for modernisation – all for nothing.” He still attends association meetings, but the numbers are going down. “The fishermen used to gather to talk, and now they’ve lost hope, they don’t come to the meetings anymore… And to think how they used to come, with the whole family.”

Henryk Indyk, the fisherman from Hel, may have accurately foretold the danger from the grey seals, but this is little consolation to him today. He is considering giving up his advocacy for the coastal fishermen. “They just don’t want to fight anymore,” he said, “and I’m tired of going everywhere for them.”

Among the reams of papers in his house in Hel, he holds onto a sticker, a memento from a trip to Denmark. The drawing on the sticker depicts the stars of the EU flag, encircling a bunched fist with an extended middle-finger – the “fuck you” gesture. The caption is in English and slightly mis-spelt: “Fishermann’s grave”.

Indyk visited Denmark on a fact-finding trip 20 years ago, on the eve of Poland’s entry into the EU. Denmark had been a member of the bloc since 1973, and the sticker was handed to him by a group of Danish coastal fishermen. It was intended as a warning: “This is what will happen when you join the EU.” After Poland joined the bloc and industrial trawlers entered its territorial waters, its coastal fishermen realised what they were up against. “For the first time in our lives,” Indyk said, “we saw what a truly big ship is like.”

This story was produced as part of the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the Erste Foundation in co-operation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Editing by Neil Arun.

Tadeusz Michrowski is an editor and fact-checker at VSquare and FRONTSTORY.PL. He is an award-winning journalist and writer.