Josef Šlerka (investigace.cz)

Anastasiia Morozova, Maciej Możański (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: ICJK 2025-10-08

Josef Šlerka (investigace.cz)

Anastasiia Morozova, Maciej Możański (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: ICJK 2025-10-08

Across the Visegrád countries, politicians have increasingly used paid social media ads to attack journalists, human rights activists, and civil society organizations. From Hungary to Slovakia, these campaigns spread disinformation, demonize independent media, and label critics as “foreign agents” or members of the “Soros network.” Sponsored content reached tens of thousands of users, often using subtle but persistent narratives that paint whole populations as enemies while evading platform moderation. Even as Meta and Google prepare to end political advertising in the EU, experts warn that algorithms favoring polarizing content leave the door open for continued manipulation and harassment online.

“They spread disinformation and hoaxes about the 1000-day war (…) they deserve the Singapore approach (a hard, blunt, long wooden object on the head, that’s how it works in Singapore, in case you didn’t know).” This is what an attack on journalists on social media, complete with a call for violence against them, can look like. This one comes from former nationalist Slovak politician, Ján Slota’s son, Pavol Slota, chairman of the extra-parliamentary party DOMOV. He has also long been spreading Russian propaganda too. Slota has spent over €26,000 on his social media profile.

However, this is more than a simple post on social media: at the same time, it is also a political ad running on Meta’s platforms. Thanks to this sponsorship, the content reached nearly 3000 users on Facebook. This is just one of many problematic paid advertisements attacking journalists and the non-governmental sector over the past year in the Visegrád countries.

As part of the Sponsored Hate project, we analyzed thousands of paid political ads in the Visegrád Four countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia). This investigation was conducted under the coordination of the Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak (ICJK), in collaboration with VSquare, FRONTSTORY.PL and Investigace.cz.

We examined paid political content over a one-year period from July 2024 to June 2025. In total, we identified 773 hateful political ads on Meta platforms that used offensive or derogatory language. According to data from Meta’s ad archive, the company could have earned up to tens of thousands of euros for similar attacks in Central Europe.

On social media, paid political ads have become an effective tool for attacking the media, journalists, and civil society. Slovakia was the biggest source of this kind of hateful content within the Visegrád Four. Politicians spent tens of thousands of euros on paid political ads to systematically undermine public trust in critical voices.

According to Csaba Molnár, head of research at the Budapest-based Political Capital think tank, political ads are characterized by the use of so-called “enemy narratives,” which aim to mislead, cause confusion, and deliberately distort reality. Since these are not explicit expressions of hatred, “content of this nature is not detected by platform systems,” explains Molnár. Paid political ads mostly attacked through so-called enemy narratives—accusing journalists and NGOs of treason, spreading lies, or defending foreign interests, all without violating the social media platforms’ terms.

We also shared our findings from the four countries with Meta and Google. According to a brief statement by Alžbeta Houzarová, Google’s communications manager for the Czech Republic and Slovakia, “we have strict rules regarding the type of ads that are allowed on our platforms. These rules are publicly available, and we enforce them consistently and impartially. If we find ads that violate these rules, we remove them promptly.” Meta did not respond to our questions by the deadline, nor did its Oversight Board, which reviews the most complex content decisions.

In the coming weeks, the situation on these social networks will change significantly, as political advertising in the EU will end due to new transparency rules. However, experts warn that this may not mean the end of risks. The algorithms these platforms use naturally favor negative and polarizing content, which opens the door to inauthentic interventions—from bots to networks of fake accounts—that can circumvent official rules and continue to shape public debate.

According to Daniel Hegedüs, regional director of the German Marshall Fund, authoritarian and radical political forces with narratives directed against elites “relatively easily stigmatize their political opponents as a corrupt elite that needs to be dealt with.” However, he believes that journalists and activists cannot be so easily smeared because they still have a major influence on how voters perceive political events and how they view certain issues. “On the one hand, they are very convenient opponents because they have no other sources of power than their moral capital and publicity,” explains the political scientist, but on the other hand, he adds that the issues they frequently address (minority rights, human rights, etc.) also “make them a very easy punching bag.”

The Situation is Worst in Slovakia Thanks to the Governing Smer Party

Although we examined all four Visegrád countries, Slovakia stood out. Almost 70 percent of all identified hateful advertisements came from Slovak political actors – mainly from the governing coalition. Government representatives often sponsored their posts, which included attacks on journalists and the media. They spent thousands of euros toward this end. Our in-depth analysis showed that, in the 12 months examined, up to 450 identified attacks (out of 524) came from a government politician or political party, which represents up to 85 percent.

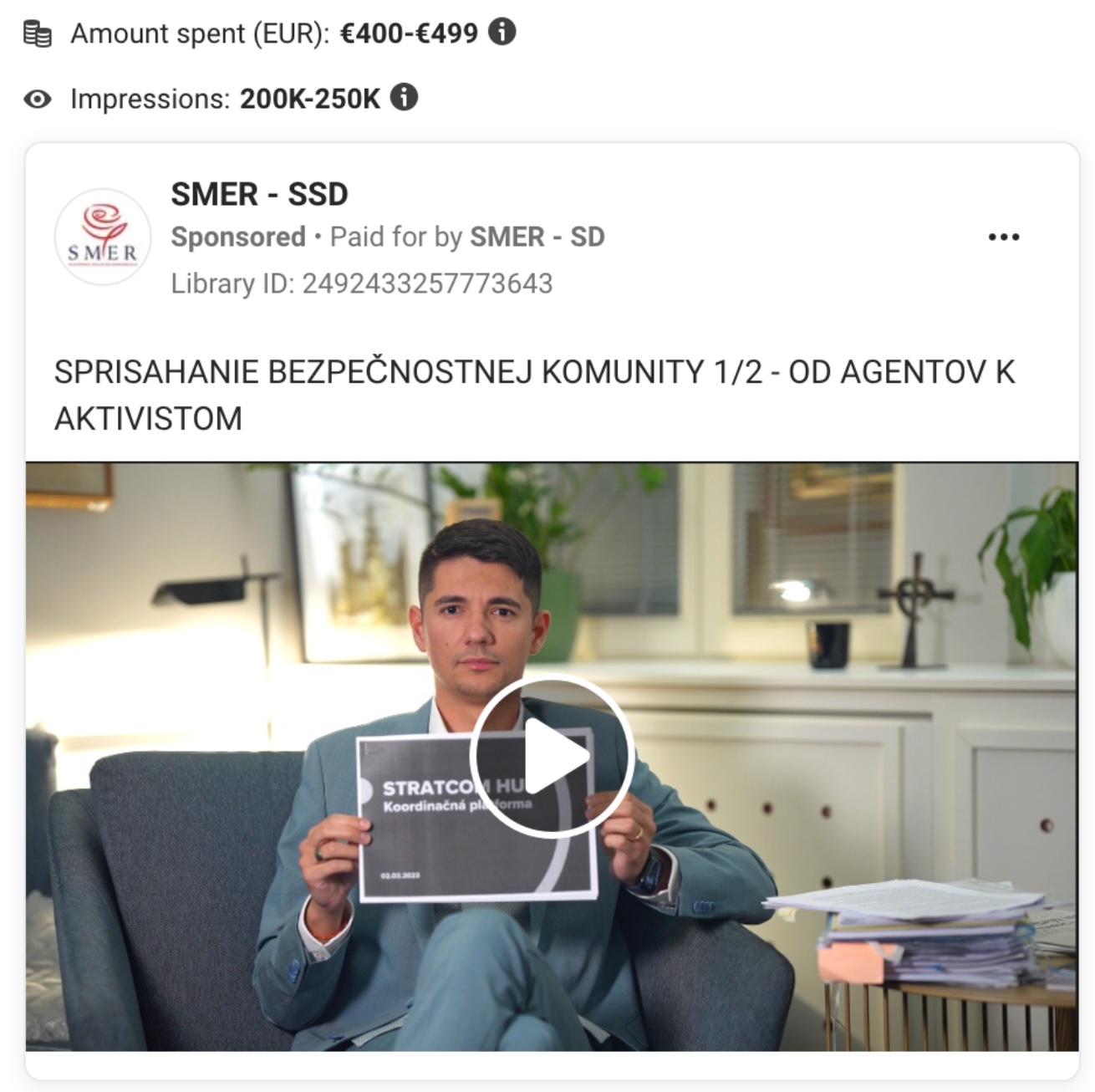

In April of this year, Erik Kaliňák, chief advisor to Prime Minister Robert Fico, recorded a video in which he attacked the non-governmental sector, spoke of a “conspiracy by the security community,” and claimed that organizations supported by USAID, among others, were defending foreign interests. The dissemination of the post, published on the central profile of the SMER party, was also supported by paid political advertising. According to Meta’s ad library, the ruling party spent between €400 and €499 on this, the most among the ads examined. Meta’s ad library estimates the reach of this post at nearly 90,000.

Erik Kaliňák’s ad. Source: Meta ad library

However, this is not the only such attack by Smer. More than one-fifth (117 cases) of the identified attacks from Slovakia came from Robert Fico’s party. More importantly, however, the vast majority of attacking and defamatory paid posts were also sponsored by Smer (up to 65 percent of the Slovak cases). In practice, this means that even if a post appeared on the profile of, for example, a government MP, the advertisement for it was paid for by the party. (Since 2019, Smer has spent almost €200,000 on the Meta platform.)

Matúš Šutaj Eštok, a former member of Smer and now chairman of the coalition party Hlas-SD, came second in terms of the number of offensive ads. According to the Meta system, he paid for the ads himself. Over €166,000 was spent on sponsoring posts on his profile. In the past, the Smer party also paid for his ads.

Attacks directly targeting specific journalists and editorial offices have become part of Slovak public discourse both online and offline. In our analysis, we identified 88 unique targets of sponsored attacks, whether specific individuals or organizations. In the case of the media, these included 22 editorial offices and 37 named journalists. The most frequent Slovak targets were three editorial offices: Denník N, SME, and Aktuality. The first was mentioned a total of 79 times in offensive sponsored posts; SME 45 times; and Aktuality 30 times.

In Hungary, Attacks Are Carried Out Directly with Public Funds

In Hungary, 193 paid political advertisements were spread on Meta platforms, attacking journalists, civil society organizations, and human rights activists. The campaigns often used the narrative of the “Soros network” or “foreign agents” with the aim of delegitimizing independent media and civil society. Many of the ads were linked to pro-government institutions, such as the Sovereignty Protection Office (SPO), which used public funds to finance the defamatory content.

The most frequent attacks came from the profile of the parliamentary faction of the ruling Fidesz party and its chairman, Máté Kocsis. Viktor Orbán’s government attacks journalists and the non-governmental sector not only verbally, but also through various laws against NGOs and, most recently, through the SPO, which, according to Political Capital, serves to suppress independent media and civil society in Hungary. Smear campaigns launched under this pretext were financed by millions of forints from public funds via both Meta and Google platforms. These posts often portrayed specific journalists and civil society organizations as “foreign agents” or “members of the Soros network.”

“Átlátszó systematically abuses data of public interest, and its intelligence and disinformation activities seriously violate Hungary’s sovereignty.” This specific example comes from the Facebook page of the Office for the Protection of Sovereignty, which was even promoted in the form of a political advertisement to reach a wider audience. At a cost of at least €320 (125,000 forints) of public money, this enabled them to reach 90,000 users.

The party also paid for the dissemination of Orbán’s speech on March 15 this year, in which he called his opponents stink bugs that need to be cleaned out. “We will dismantle the financial mechanism that bought politicians, judges, journalists, pseudo-civil organizations, and political activists with corrupt dollars. We will dismantle the entire shadow army. (…) Their fate is shame and contempt. If justice exists, and it does, a special place awaits them in hell.” The party sponsored these words four times.

In the Czech Republic, Public Media Were the Most Frequent Target

In the Czech Republic, paid political advertisements, especially those associated with the far-right SPD and far-left STAČILO! parties were used to directly attack the media and specific journalists. The most frequent target was public service media, especially Czech Television. In the advertisements, it is portrayed as corrupt, manipulative, pro-government, biased, wasteful, and law-breaking. Extremely offensive terms such as “protection money for cronies,” “tool of Brussels propaganda,” and even “Goebbels-style propaganda” were used to discredit it. Private media outlets such as Seznam Zprávy, Novinky.cz, and Forum 24 have also been targeted, being labeled as “trash” and “corrupt media,” while their employees were dubbed “hyenas.” However, the number of attacks lags far behind Slovakia and Hungary. In the 12 months examined, we identified only 47 Czech attacks on Meta’s platforms.

The attacks are often personalized, which increases their effectiveness and aims to discredit specific figures associated with investigative and political journalism. Václav Moravec and his program Otázky Václava Moravce (Václav Moravec’s Questions) have become a repeated target, as have Nora Fridrichová and the editorial staff of the program Reportéři ČT (ČT Reporters). The attacks also targeted other journalists, including Karolina Brodníčková (Novinky.cz), Martina Machová (Novinky.cz), Jan Moláček (ČT), and Pavel Šafr (Forum 24). All are accused of writing false and manipulative articles.

In addition to discrediting institutions and individuals, these paid advertisements contribute to a dangerous social phenomenon: the normalization and escalation of hatred towards journalists as a professional group. The language used in these advertisements is often dehumanizing. Labeling journalists as “hyenas and idiots,” their work as “rubbish,” or comparing them to Nazi propagandists pushes the boundaries of public debate and creates an atmosphere in which aggression towards journalists is perceived as acceptable. A concrete example of this strategy is the tactic used by far-right SPD leader Tomio Okamura, who physically confronts and films journalists, thereby normalizing their harassment and intimidation.

In Poland, Such Attacks Are Not in Style

Poland differs from other countries in the region. The strategy of targeting journalists with sponsored hate through paid campaigns is thriving in Slovakia and Hungary. In Poland, such campaigns are much more often directed at other groups, like refugees, for example. The National Computer Security Incident Response Team, which operates within the Research and Academic Computer Network – State Research Institute (NASK), when asked whether it had observed any cases of paid advertisements attacking journalists and the media on the platforms monitored by NASK over the past year, replied only that it was aware of cases of fraud using journalists’ images and that it was “closely monitoring the matter”. During the period under review, we found only 10 attacks on Meta platforms.

As dr. Konrad Maj, head of the Centre for Social and Technological Innovation at SWPS University and assistant professor at the Department of Social Psychology at the University of Warsaw, explained, “We have a specific political situation in Poland, namely a duopoly. From a rational point of view, attacking journalists is not the best solution. In Poland, there is a certain resistance to open attacks on journalists. Without stable, strong political backing, it is simply not profitable in the long run. Doing this in the media space from a business or political perspective is like playing on someone else’s turf. That is why politicians try to be polite and engage in small talk. Caution prevails – they try to manipulate the media rather than deal with them in a very dirty, harsh way”.

In April this year, Law and Justice (PiS) MP Kacper Płażyński accused journalists and activists in paid advertisements of allowing “foreign powers to control Poland”. According to Płażyński, grants and subsidies from foreign NGOs were used to “support those who actively fought against the conservative Law and Justice government.”

Krzysztof Muława, an MP from the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party, acts in a similar manner. Over a year ago, in August, he discredited journalists as government propagandists in paid advertisements on Facebook and Instagram. He claimed that the public television station TVP was persuading citizens to migrate illegally.

The End of Political Advertising?

This fall marked a turning point: Meta and Google announced that they would stop displaying political ads in the European Union. The decision to completely withdraw paid political advertising in the EU was due to the introduction of regulations on the transparency and targeting of political advertising (TTPA), which, according to the company, introduce significant operational challenges and legal uncertainty.

Google turned off political advertising in the second half of September. It also deleted information in its Transparency Center regarding sponsored content in the EU. As a result, it is no longer possible to trace who paid for what political content or how much was spent on their platforms.

According to Csaba Molnár, analyst at Political Capital, after the shutdown of political advertising on the platforms of these two tech giants, “organic reach will be key.” However, the analyst predicts that politically charged ads will slip through the platforms’ filters: “[G]iven the relatively high attention they will receive, they will not have a long-term effect.” Molnár adds that there is also another possibility of inauthentic interventions, “Which will try to increase the visibility of certain content and narratives by circumventing the platforms’ algorithms.”

However, Dániel Hegedüs of the German Marshall Fund also points out another aspect. Paid advertising can be stopped, but if the social networks’ algorithm itself favors polarizing and hateful narratives and there are no protective mechanisms in place, the system will remain just as manipulable. “If someone has enough money, resources, and knowledge, they can still create a network of thousands of bots or fake profiles and still be able to use algorithms to spread their own destructive, anti-democratic messages,” he warns.

This investigation was conducted under the coordination of Investigative Centre of Jan Kuciak (Slovakia), in collaboration with Frontstory.pl (Poland), Investigace.cz (Czech Republic) and VSquare.org (Central and Eastern Europe).

The production of this investigation was supported by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund.

Karin Kőváry Sólymos is a Slovak journalist at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak. Previously, she was an editor and presenter at the Hungarian channel of the Slovak public service media. During her university years, she was an analyst for the only fact-checking portal in Slovakia. She was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.