Magdalena Lemańska, Paulina Mazurek, Konrad Szczygieł (Fundacja Reporterów) 2019-12-18

Magdalena Lemańska, Paulina Mazurek, Konrad Szczygieł (Fundacja Reporterów) 2019-12-18

With almost five hundred media outlets owned by a single pro-government foundation and hundreds of millions of euros of state advertising transferred annually to fund it, Hungary’s right-wing government has built Europe’s largest propaganda machine since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Warsaw follows in Budapest’s footsteps with a growing stream of taxpayers’ money funnelled to media outlets that openly support the ruling party. Both governments are then repaid in kind with propaganda broadcasts created by journalists who never seem inclined to ask any hard questions.

On 7 April 2018, a day before Hungary’s general election, all nineteen regional newspapers ran the same front-page interview with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The headlines encouraged voters to cast ‘Both votes to Fidesz!’ Soon, it became clear that the right-wing conservative party, which now enjoys a two-thirds majority in the country’s parliament, secured its third consecutive election victory.

According to official records, all those regional newspapers were in private hands. Fourteen of them were owned by Lőrinc Mészáros, Orbán’s childhood friend and one of the country’s wealthiest businessmen. Three were controlled by Heinrich Pecina, a somewhat shady Austrian businessman who became notorious in 2016 for shutting down Népszabadság – a liberal leftist daily. The owner of two other newspapers was the late Andrew G. Vajna – a Hollywood producer who turned media mogul in Orbán’s Hungary and is known for his Rambo and Terminator franchises.

United they stand

In November 2018, a few months after the general election, Lőrinc Mészáros bought all regional newspapers owned by Pecina and Vajna. On the same day, he transferred all of those assets to the newly-founded Central European Press and Media Foundation (CEPMF), headed by a newspaper publisher known his loyal support of Viktor Orbán. The assets were a gift and were transferred for free. Owners of other media outlets that supported Fidesz followed suit. They included Mária Schmidt, chief historian of the Hungarian government, or Ádám Matolcsy, the son of Hungary’s central bank president, who also transferred their media outlets to the foundation.

As a result, CEPMF became Hungary’s most significant media owner. Its domain now spans 14 media groups and 476 media outlets that include cable news channels, news websites, tabloid and sports newspapers, all of the country’s regional newspapers, several radio stations and numerous magazines. According to the restrictions included in 2011 media law on ownership limitations, such conglomerate should have been banned by the Media Authority and the Competition Authority. Still, the government signed a decree which changed the status of the new legal entity, branding it of ‘national strategic importance,’ and thus releasing it from the supervisory process.

But even before the merger, it was clear that private pro-government media (officially labelled as independent) worked hand-in-hand with the government whenever there was an important message to push. The same pro-government propaganda was spread by every news website, newspaper, TV or radio channel – telltale signs of a highly centralised political messaging.

This heavy political machinery was used to slander opposition candidates before the 2018 general elections. The country’s media outlets deliberately created and published fake news, which allowed Fidesz to win the bid to remain in power. That, in turn, resulted in over a hundred lawsuits won later that year by those wrongly accused by government-aligned media.

The strategy seems to have paid off, literally. According to data collected by Átlátszó and the Mérték Média Monitor think tank, between 2010 and 2018 the Hungarian state (which includes state-run organisation, municipalities or state-controlled company) spent EUR 1.2 billion on advertising campaigns. Orbán’s second (2010-2014) and third (2014-2018) government spent EUR 235.3 million on propaganda, and the expenditure was labelled ‘governmental information campaigns.’ Most of that amount was transferred to loyal media outlets, fuelling the rise of the pro-Orbán media ecosystem.

State advertising is the primary source of income for the pro-government news media outlets, including a state-run public media broadcaster with an annual budget of EUR 260 million (2019), which amounts to 25 per cent of Hungary’s total news media market revenue. According to data obtained by a market research company Kantar, in 2018, pro-government private media received EUR 225 million in state advertising.

“If needed, we shoot immediately”

By funding such outlets, the government gets uncritical loyalty and the power of propaganda. The media outlets use a wide range of tools, including disinformation, smear campaigns, labelling, defamation, libel, fake news, conspiracy theories, trolling and online harassment – all of this aimed at rival politicians, civil organisations and journalists. Some of their campaigns gained international attention, including the anti-migrant campaign, the drive to discredit Soros or the pro-Russia stance of the Fidesz media.

Domestic opponents of the Hungarian government are pelted with heavy use of images that have been put out of context or manipulated, stories that have been fabricated, anonymous ‘sources’, unverifiable ‘victims’, fake ‘experts’ and a sea of disinformation. In recent years, Orbán’s government has led a coordinated homophobic campaign and accused opposition politicians of same-sex tendencies, propagating Islam, sexual misconduct, domestic violence, unethical business practices or outright corruption. There have been instances of character assassinations when independent or critical journalists and NGOs e labelled as Soros puppets, traitors, people who lack patriotism, news fakers. In an interview the editor-in-chief of the pro-government 888.hu news site Gábor G. Fodor openly divulged on his strategy, saying ‘We do politics. We are warriors, and we are not ashamed of it. […] If needed, we shoot immediately.’

Partisanship, bias, fabricated news, lies – all have a long history in the local media sector that predates Orbán’s rule. Media scholar Péter Bajomi-Lázár retrospectively described the privatisation of the Hungarian media outlets after the fall of socialism as ‘party-colonisation’. A majority of the country’s political parties had become surrounded by allied newspapers, TV and radio channels or enjoy the favour of at least some media mogul. In contrast, the state-controlled public media broadcaster was obliged by law to represent all political parties.

Historical roots of the media war in Hungary

In 2010, Fidesz’s victory in the general election secured the party a two-thirds majority in the Hungarian Parliament. As a result, Orbán’s government took over the public broadcaster and subsequently turned it into a propaganda machine. The country’s media sector saw an exodus of multinational capital while the number of government-allied private news outlets continued to grow. Many media outlets that used to be in private hands were taken over by government-aligned Hungarian entrepreneurs, who set up their own companies.

The idea that public money may (or should) be used as an effective means of balancing’ the alleged political inequalities of the media sector to favour pro-government outlets is nothing new. It is deeply ingrained in the ideology of renationalising the media, which was one of Viktor Orbán’s main goals after his rise to power for the second time in 2010.

For a few years after 2010, the Hungarian government and its supporters claimed that between 2002 and 2010 (when Orbán was in the opposition), the country’s socialist governments had no reservations about supporting leftist-liberal outlets by using them to advertise state-controlled companies. This claim that the state was corrupted and misused public funds went unchecked until some comparative studies were recently published, the first such studies since 2013. Mérték Media Monitor reported that although the socialist-liberal government spent more money on advertising in leftist-liberal media compared to right-wing ones, the real beneficiaries were multinational and independent outlets not affiliated with any political camp.

Recent studies also revealed that before Orbán’s win in 2010, state expenditure reflected the market share and audience measures of the beneficiaries, which means that state-controlled companies and institutions acted like commercial entities that pay for the size of the audience.

In the political newspapers sector, for instance, 65 per cent of readers supported leftist-liberal outlets and 35 per cent who favoured pro-Fidesz newspapers. It turned out that revenue from advertisements commissioned by the state reflected their market circulation. After 2010, the division of state expenditure changed radically. An average of 10 per cent of state funding was spent on leftist or liberal outlets, and 90 per cent went to support right-wing media. Similar changes affected weekly newspapers, television, radio, billboard and online advertising sectors. Also, there was a significant increase in the state advertising expenditure from EUR 58 million in 2010 to EUR 316 million in 2018.

Initially, the post-2010 move to redirect state advertising to Fidesz-aligned media looked like clear-cut fraud. The system masterminded by Orbán’s friend and former Fidesz party treasurer Lajos Simicska had a whiff of a classic corruption scheme. First, Simicska transferred his representatives to public administration and state-controlled companies. Then, those entities awarded contracts to media agencies linked to Simicska. Finally, those agencies spent most of their ever-increasing budgets on ads bought in pro-government media outlets owned by Orbán’s friend.

A CEO of a multinational media agency whom we spoke to said that the agency knew that several pro-government media companies simply failed to come up with any audience measurements that would justify the spending. The headquarters approved the expenditure anyway. ‘The client decides where to spend the money, so the client is held responsible if the public money is misused for corruption,’ this is what our source heard when he called the headquarters and asked whether it was a problem to have government contracts under the Orbán government. As a result, the advertising spending lacked any business sense and, quite unsurprisingly, was directed at pro-government outlets only.

Poland following Hungary’s footsteps

In an ideal world, the media should work on the following principle – an advertiser pays for an ad in, let’s say, a newspaper. The newspaper prints the ad, and uses the money to pay its staff (including journalists) and the printing house. The advertiser wields no influence over the content printed by the newspaper, an ideal fusion of the free-market economy and freedom of speech.

The problem is that Hungary and Poland seem to be far off from that idea. Back in the 1990s, the Polish media sector became gradually dependent on state-controlled companies. Those entities, controlled by the treasury, had huge promotion and advertising budgets, which often were not linked to the current market status. And they started using those budgets to fund the media. Today, many media outlets in Poland are overdependent on the system. Either you get state advertising, or you go down.

During the rule of the progressive Platforma Obywatelska (Civic Platform), state-controlled entities were more likely to advertise in liberal media, such as Gazeta Wyborcza, TVN, Polityka and Newsweek. In return, the party enjoyed the support of those outlets, but that support was anything but mindless pro-government propaganda. The liberal media continued to expose major scandals that involved those in power.

Everything changed when the right-wing Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice or PiS) came to power in 2015. It carried out a wide-sweeping reshuffle at state-controlled companies replacing their heads with people loyal to the party. Then, state advertising funding began flowing in the opposite direction. But the scale of the media support for the PiS government also turned out to be unprecedented, likely matching the increased monetary transfers. In current advertising campaigns, media outlets are no longer chosen because of their reach or efficiency, but solely on their readiness to support those in power.

The editors of such outlets often do not even try to pretend they are objective. Every single story seems to extol the virtue of PiS. The message is consistent – the more successful Jarosław Kaczyński’s party is, the more fiercely it is attacked by those who defend the old system. What’s characteristic and typical of populist propaganda, the enemy is portrayed as a united front of the opposition, judges, Germans, George Soros, former secret services, Timmermans, LGBT movement and environmental activists. All seem to be heads of the same hydra. The Polish and Hungarian narratives are nearly identical copies.

Philanthropism of patriotism

In February 2018, the right-wing Gazeta Polska organised the Man of the Year award gala at the National Philharmonic in Warsaw. The niche weekly sells about 20,000 copies a week in a country of 38 million and is unrepentantly pro-government.

Sitting in the front row were Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki and Jarosław Kaczyński (the party chair who runs Poland from the back seat). Next to them sat Tomasz Sakiewicz, the editor-in-chief of Gazeta Polska and the gala’s host. Onstage, Sakiewicz complimented the Prime Minister and called him a ‘philanthropist of patriotism’. He also said that Morawiecki had ‘taken up a fight against the worst dysfunction’. Morawiecki is going to receive the Man of the Year award.

The gala was formal and dignified. During the event, logos of the biggest state-controlled companies that sponsored the event were displayed on the screen and read out loud for the audience. Their CEOs, who were appointed by the Prime Minister and Jarosław Kaczyński, have all supported the event. Gazeta Polska is one of the biggest beneficiaries of their corporate advertising budgets.

Gazeta Polska aside, there are two other right-wing weeklies in Poland, Sieci and Do Rzeczy, Both can attract Poland’s most influential people in one place. Every year, they organise events in the country’s biggest auditoria to praise ruling party politicians and those who support the government. State-controlled companies bear a majority of the cost of those events.

All three newspapers are among a group of right-wing media outlets which are the go-to choice for state-controlled advertisers. ‘This scale of public funding for the media is unprecedented in the history of Poland after 1992,’ concludes Tadeusz Kowalski, a media expert and a professor at the University of Warsaw, who has penned a report on treasury companies’ spending on media advertising.

After 2015, the advertising budgets of treasury companies rapidly spiked from EUR 163 million (PLN 700 million) to almost EUR 232 million over the next three years. Last year, half of that money was transferred to pro-government media.

Kowalski’s analysis shows that a majority of the companies that support pro-government media represent the energy, fuel, finance and insurance sectors. They are, simply put, the richest ones.

The biggest advertiser is Totalizator Sportowy, which runs a nationwide lottery. Since 2015, it has spent an additional EUR 11.5 million more compared to a period before PiS took over and a total of EUR 4 million in pro-government media alone.

How much money flows from state-controlled entities to specific outlets? The pro-government Gazeta Polska has reported an enormous increase in advertising revenue from state-controlled companies – from EUR 49,000 in 2015 to EUR 1.8 million in 2018*. All this happened while the weekly’s circulation slumped from 31,000 copies in 2018 to 22,000 in the autumn of 2019.

The sales of other right-wing weeklies have been going down too. Sieci by nearly -40 per cent, and Do Rzeczy by more than -22 per cent. At the same time, advertising revenue from state-controlled entities skyrocketed, which would be hard to imagine in free-market conditions. In the case of Sieci from PLN 115,000 in 2015 to PLN 2.6 million in 2018, and Do Rzeczy from PLN 189,000 in 2015 to PLN 1.3 million in 2018.

Fighting a war of ideology

So why – despite their weakening market position – are the pro-government media in Hungary and Poland receiving so much money from state-controlled entities? The answer is simple. Because they know how to reciprocate. They no longer ask difficult questions. Those in power enjoy being interviewed in a relaxed and friendly atmosphere. Money from state advertising also helps politicians to appear in favourable media to present even the most painful decisions in a positive light. After 2015, state-controlled outlets have failed to expose any major scandal that involved the ruling camp and might have influenced the public debate.

On the other hand, pro-government media are always on the lookout to undermine the opposition. In Poland, they also publish articles that anticipate publications planned by the media that are critical of the government. In those articles, spokespeople of state agenda neutralise any problematic questions before journalists get a chance to ask any questions.

Today, right-wing media fight an ideological war against gender, LGBT and refugees. They strictly follow the narrative of the ruling parties. In the summer of 2019, during Poland’s general election campaign Jarosław Kaczyński announced that the LGBT movement and gender ideology are a threat to traditional values, the country’s culture and the Catholic church. Gazeta Polska reinforced the message when it included ‘LGBT-free zone’ stickers with its latest issue.

When the party engaged in strong anti-migrant rhetoric, the cover of the Do Rzeczy weekly read: ‘They are invaders, not refugees.’ Sieci’s front page depicted a white woman representing Europe grabbed and pulled in all directions by dark-skinned male hands. The title screamed ‘The Islamic rape of Europe.’

When trust is gone

Before 2014, Orbán’s friend Simicska was the owner or shareholder of several Hungarian media outlets, including the daily Magyar Nemzet, the weekly Heti Válasz, the Fox News-like Hír TV, the freemium daily Metropol, the nationwide commercial radio Class FM, the talk radio Lánchíd Rádió, and several billboard companies like Publimont, Mahir Cityposter, EuroAWK and Euro Publicity. But when Simicska and Orbán broke up after the 2014 general elections, the ruling Fidesz found the whole situation deeply uncomfortable.

It soon became clear that the government briefly lost its most influential media partners (except those not controlled by Simicska). His decision to break off ties with Hungary’s PM was openly denounced as treason, while journalists who were Simicska’s employees were typecast as traitors of the ‘common cause.’

After the scandal, state-controlled entities immediately ceased advertising in Simicska’s media empire, although many of his journalists still supported the government. In 2018, when his weekly was shut down, Gábor Borókai editor-in-chief of Heti Válasz admitted in his farewell piece that ‘most of the government’s directions are right.’ Simicska’s war against Orbán lasted three years until his financial resources dried up, forcing him to hand over the remaining assets to entrepreneurs who remained loyal to the prime minister.

By that time, new state funding helped create an entirely new, pro-Orbán network of news outlets, which revered Hungary’s leader. They were mainly owned by people loyal to Orbán, including Lőrinc Mészáros, a former gas-fitter, who became Hungary’s wealthiest businessman. Other figures, such as Mészáros, a childhood friend of Hungary’s PM and former mayor of Felcsút (Orbán’s home village) became aware of Simicska’s fate. They would never question Orbán’s authority over the assets they acquired.

During the effort to re-build Fidesz’s media empire, many companies previously owned by multinational media houses ended up in the hands of such businesspeople. They included a commercial TV channel called TV2, eighteen regional newspapers previously owned by the German WAZ-Funke Group, the Austrian Russmedia and Mediaworks and the American Lapcom as well as the largest internet news website, Origo, formerly owned by Magyar Telekom, the country’s subsidiary of Deutsche Telekom.

Fidesz loyalists also set up new outlets, including Modern Media Group owned by the party’s campaign guru, Árpád Habony, or the daily Magyar Idők founded by journalists who left Magyar Nemzet after the scandal. When these news outlets were launched, state funding started to pour in, although the advertisers failed to commission the latest readership data.

Money goes where the support is

The spending policy of state-controlled companies can be illustrated by Poland’s two best-selling newspapers, which sharply criticised the ruling party. One is the liberal tabloid Fakt, and the other is the opposition daily Gazeta Wyborcza. Data provided by Kantar Media, included in Tadeusz Kowalski’s report, shows that in 2018 they sold an average of 243,000 and 94,000 copies, respectively. Their share in advertising revenue is negligible – 1.3 per cent (Fakt) and 0.4 per cent (Gazeta). A significant departure compared to previous governments.

In 2018, Fakt cashed in EUR 443,000, merely 19 per cent of the 2015 revenue. Fakt is also Poland’s most popular tabloid, which exposed the government’s unreasonable spending, kept tabs on politicians’ lies and blunders and often had to deal with hostile attacks coming from PiS politicians. In reaction to an article published by Fakt, Krystyna Pawłowicz, a former MP and current judge of the Constitutional Tribunal called it ‘German reptile journalist’ (an offensive term given to Polish-language newspapers published by the German occupational authorities during WWII). PiS politicians often voice such allegations because the ruling party believes that Fakt, which is owned by a Swiss-German group Ringier Axel Springer, is acting in foreign interests. This has recently changed as journalists critical of the government recently left the newspaper, and Fakt has softened its rhetoric.

‘As far as private TV stations are concerned, there are also significant differences in where state companies spend their budgets,’ says Tadeusz Kowalski in his analysis. ‘This is clear from a comparison of [private TV stations] TVN and Polsat, which have similar viewership figures. The former, considered to favour the opposition, gets over 2.5 times less than the latter. Only three state-controlled companies purchased advertising time in TVN and spent, according to the latest data, over a million zlotys. In contrast, Polsat has been supported by twelve state-controlled entities.’

Kowalski suspects that the reason for such imbalance is Polsat’s turn towards PiS. According to the expert, this is how the media in Poland are rewarded for taking a favourable stance on the ruling party.

In 2018, Newsweek reported that Polsat had taken a turn to the right. Its owner Zygmunt Solorz, one of Poland’s wealthiest businessmen, was planning significant investments in the energy sector and needed to win the government’s favour. He also had some outstanding financial penalties, the enforcement of which depended on government decisions.

Polsat, therefore, hired a new head of the news team, and politicians representing the ruling party, including the PM and President, soon were more frequent guests on air. ‘The operation to use the network to win the government’s favour is being carried out very softly. It works like this: perhaps if Polsat turns towards PiS, fortune will smile on Zygmunt Solorz’s other investments?’ observed one of Polsat journalists.

The share of state-controlled companies in the TV advertising market is much smaller than in the press market, and it is negligible for most broadcasters. The public broadcaster TVP is an exception, as 7.4 per cent of its advertising revenue comes from such entities. Between 2015 and 2018, television networks attracted EUR 314,5 million in advertising purchased by state-controlled companies, 45 per cent of that amount supported TVP. Poland’s public broadcaster lives off the public licence fee, government grants and private advertising.

One gets what one pays for

In Poland, public television, led by a former PiS politician Jacek Kurski, is the champion of the government’s propaganda machine. After taking control of the public media, PiS fired or discontinued collaboration with about 200 journalists. TVP’s daily news programme Wiadomości tells a story of the government’s successes and the mistakes of PiS’s political competitors on a daily basis.

Almost every edition of TVP’s news programmes includes an extensive block of stories along the lines of: ‘We have asked Poles how their lives are going’. A procession of happy citizens comes and goes on the screen, telling stories of how well off they are after 2015. Their statements are certainly authentic, but they are also, of course, carefully selected. Street polls, combined with voiceover commentary, convey the image of a society that is deeply grateful to the government for the benefits it has received.

How does TVP propaganda work? When young doctors protest in Poland in 2017, TVP broadcasts a deceitful story about one of the leaders of the strike, Katarzyna Pikulska. Based on Facebook photos, the station points a finger at her for going on exotic trips, a fact supposed to prove her high income and contrast her statements on poor salaries of young doctors. In fact, Pikulska often went abroad as a member of charitable medical missions.

The patterns are similar to those one can observe in Hungary – intensive fake or misleading narratives, one-sided stories, targeted at the main fears of the society (often also created by the same media). When a referendum related to the European Union’s migrant relocation plans was held in Hungary in October 2016, the M1 public service broadcaster had a whole day of coverage on the migrants wanting to settle in Hungary in case of a failed referendum. An overwhelming majority of voters have rejected the EU’s migrant quotas but due to the low voter turnout, the referendum was considered invalid.

When a campaign before the European Parliament elections is underway in 2019, the Journalists’ Association and the Batory Foundation prepared a detailed report on stories broadcast on Polish Wiadomości news program in that period. Here is what the report says: “Qualitative and quantitative analysis of Wiadomości indicates that the programme ran content which favoured the ruling party and omitted, downplayed, ridiculed or vilified the opposition parties’ candidates and politicians by the use i.a. of fake news, picture and sound manipulations.” The politician most frequently on air at the time was the leader of PiS Jarosław Kaczyński.

In November 2019, Tomasz Grodzki, an opposition politician, was appointed the Marshal of the Senate. For the first time in four years, an opposition politician would be allowed to address the nation on the public TV in the evening time slot. About ten minutes before the address was aired, the evening news programme showed a story that focused on Grodzki’s wealth. It argued that Grodzki, a professor of medicine and a long-time director of a clinic, has accumulated significant savings and owns an expensive car. It also suggested, based on a single online entry, that he had accepted a bribe from one of his patients.

TVP’s close relationship with the ruling party is so apparent in Poland that TVP CEO Jacek Kurski did not feel uncomfortable meeting with Jarosław Kaczyński at the party’s headquarters during PiS election night in October 2019.

Photo posted by MEP Beata Mazurek on her Twitter account

Over the last four years, in addition to EUR 142 million revenue from state-controlled entities, Poland’s public broadcaster received state loans and grants amounting to EUR 793 million.

Statistics that leave no doubt

Apart from state-controlled entities, the media in Poland are also supported by state funding funnelled through various ministries, although not to the extent present in Hungary. We have sent public information disclosure requests to all Polish ministries, asking them to provide information about advertising expenditure between 2009 and 2019. We have only heard back from eleven out of eighteen ministries. The data provided is often inconsistent, selective or quite general.

For instance, the Ministry of Justice maintains that in 2016, it spent EUR 52,300 on sponsored articles published in one issue of a national journal and a nationwide biweekly, but failed to specify their names. The list of expenses also includes three promotional animations and online distribution services.

Where data seem complete, we see a similar trend as in the case of state-controlled companies.

Between 2009 and 2014, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education cooperated mainly with Gazeta Wyborcza. After 2015, when the publication became an opposition newspaper, it failed to receive even a single contract. That same year marked the end of long-lasting cooperation with the liberal broadcaster TVN, which had until then been used by the ministry quite frequently. Since 2017, the ministry has heavily invested in Super Express, the Roman-Catholic magazine Gość Niedzielny and Do Rzeczy. Since 2017, it has also bought commercial time in TVP for the amount that exceeded EUR 233,200, in Polsat – spending over EUR 70,000 and in the Roman-Catholic TV Trwam – EUR 27,500.

In Hungary, in the few cases when governing party officials responded to the questions from journalists, regarding the distribution of state funds, data has not been clear either. The officials e.g. made arbitrary calculations labelling all the media outlets outside the pro-government media conglomerate as oppositional-liberal.

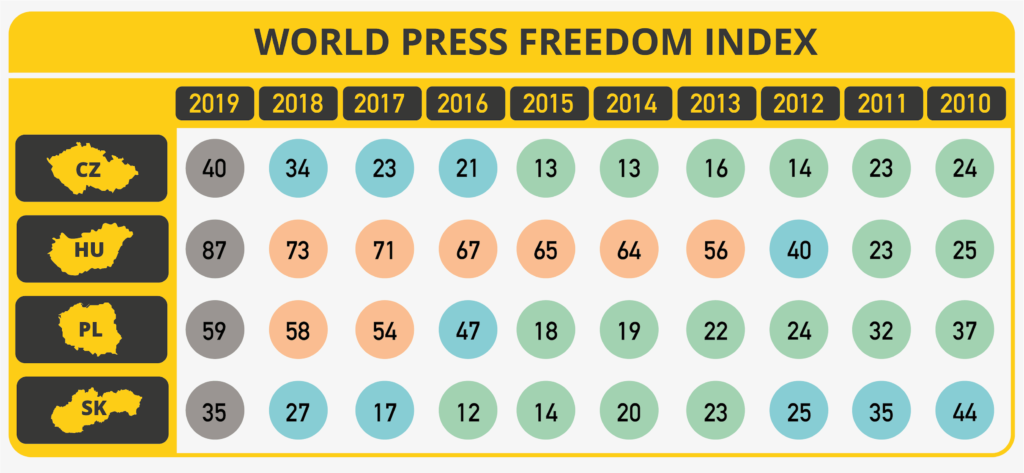

As far as data on the Polish and Hungarian media market is concerned, there is surely one statistic that leaves no doubt: since 2015, Poland has gone down by 41 positions, from 18 to 59 in 2019, in the Word Press Freedom Index prepared by Reporters Without Borders. In the same report, Hungary is located on the 87 position – compared to 65 in 2015 and 23 in 2010, when Orban came back to power.

Graphics by Lenka Matoušková; data: RSF

It is important to note that while the European Union seems to be vocal whenever press freedom is violated, Hungary’s large pro-government media conglomerate could not have been built without the silent approval of multiple European bodies. In fact, it was partly financed by EU funds since the National Development Bureau was one of the largest state advertisers. Its successor, the Government of Hungary, now handles the EU funding. Over the past eight years, the two entities have spent EUR 184 million in pro-government media. They advertised infrastructural and social programmes and bragged about the successes of the country’s authorities.

——-

* Tadeusz Kowalski’s report is based on data provided by Kantar Media that includes 123 companies controlled by the state treasury. The study focused on monitoring advertising spending in 34 newspapers, 34 magazines, 134 radio stations and 39 TV shows. The report does not include online expenditure nor cinema and outdoor advertising. The compilation prepared by the institute was based on net prices and did not include individual discounts. The data presented in the article come from Kowalski’s report, as well as Kantar’s analysis that compared media advertising spending of the 22 biggest state treasury companies in 2009-2018.

These included big state-controlled companies such as PKN Orlen, PGNiG, PZU, PGE, PLL LOT, and the PKO Group, but also private entities where the state has a majority share or which it partially controls. The latter group comprises Alior Bank (where PZU is the biggest shareholder) and Bank Pekao SA (its main shareholders are PZU and the Polish Development Fund, owned by the state treasury). Totalizator Sportowy is currently the leader among state advertisers. Over the past ten years, it has spent almost PLN 1.1 billion on media advertising, PLN 204 million of which was spent last year. In 2009, combined advertising expenditure of all of those companies totalled PLN 347 million, and in 2018, it amounted to PLN 458.5 million. The media were divided into two groups – those in favour of the current PiS government and the remaining ones. The former group includes Sieci Prawdy, Gazeta Polska and Gazeta Polska Codziennie, TVP, Polskie Radio, Nasz Dziennik, Wprost and Do Rzeczy, the latter Gazeta Wyborcza, Super Express, Fakt, Rzeczpospolita, Tygodnik Powszechny, Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, Polityka, Newsweek, TVN, Polsat, TV 4, TV Puls, Radio Złote Przeboje, RMF FM, Radio ZET, Eska, Vox Fm and TOK FM. Information on the penetration of the specific media is based on data obtained from Związek Kontroli Dystrybucji Prasy (the National Circulation Audit Office).

.

* source: Kantar Media

Attila Bátorfy is data journalist at Átlátszó, master teacher of journalism and media studies at the Media Department of Eötvös Loránd Science University, and research fellow at CEU CMDS.

Konrad Szczygieł is an investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL. Previously, he was a reporter at Superwizjer TVN and OKO.Press. Since 2016, he has worked with Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He was shortlisted for a Grand Press award (2016, 2021) and an Andrzej Woyciechowski award (2021). He is based in Warsaw.