In June 2021 in a Bratislava supermarket parking lot, a spy working for Russia’s military intelligence, the GRU, hit a Slovak woman with his car. The 51-year-old woman was taken to hospital with serious injuries. However, unlike some other incidents in previous years, this was far from an elaborate assassination attempt from the Russian spy agency, which is known for its deadly attacks on European soil.

But this undercover GRU agent, a round-faced, short-haired man in his late 30s posing as a diplomat at the Russian Embassy in Bratislava, was in fact simply driving drunk. The man was driving his Volkswagen uncontrollably in the parking lot and on the sidewalk, and he hit the woman in said parking lot while she was loading her groceries, according to Slovak media reports on the incident.

In the beginning, Slovak police did not reveal the man’s identity, only stating that they couldn’t prosecute him in accordance with the Vienna Convention. Later, however, media reports identified the diplomat as Anton Goriev, also revealing that he refused a breathalyzer test, left the scene, and apologized the next day to the family of the woman he hit.

Goriev got away with drunk driving—but not with espionage.

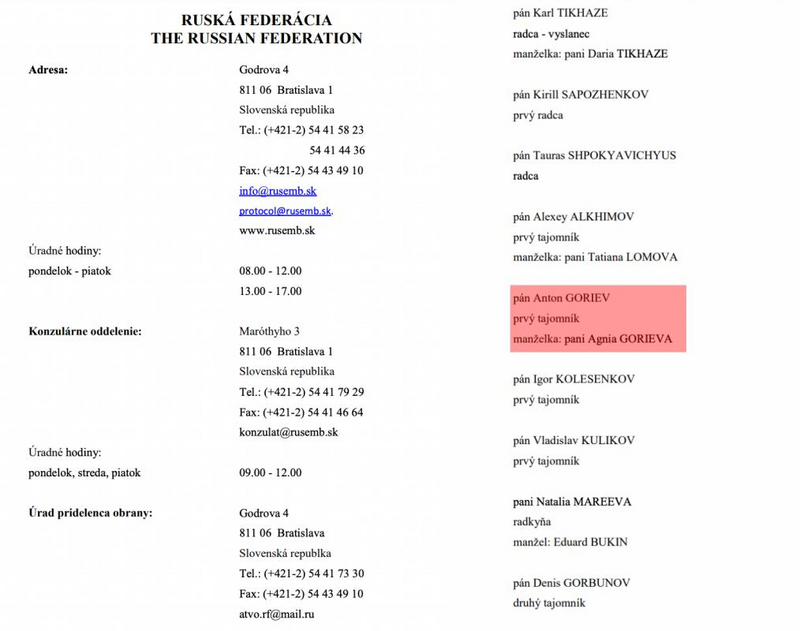

A few months later, in the spring of 2022, Anton Goriev was among the dozens of Russian diplomats officially expelled from Slovakia for espionage, VSquare and Slovak partner ICJK.sk have found based on our examination of Slovak foreign ministry documents.

Anton Goriev and his wife Agnia were on the list of diplomats accredited in the Slovak Republic from 2020 to 2022. Source: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Slovak Republic

In March 2022, Slovakia first expelled three diplomats and detained three people. It went on to curtail the overall number of the Russian Embassy in Bratislava and sent home 35 embassy staff. It was part of a joint Western effort to respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the course of a few weeks, hundreds of Russian spies working under diplomatic cover were booted out from EU and NATO countries.

VSquare, as part of the #ESPIOMATS project, a collaboration of international journalists working to identify the hundreds of Russian diplomats expelled in 2022, investigated the history of Anton Goriev’s activities. We found that Goriev first worked for a GRU military unit, then spent around eight years in Budapest, likely from 2012 until 2019. A former Hungarian counterintelligence officer claimed that Goriev was known to be an “identified intelligence officer” by Viktor Orbán’s government since the Russian spy’s arrival to Budapest in the early 2010s.

However, Hungarian security agencies still let Goriev network and mingle with both Hungary’s far-left and far-right radicals during his lengthy stay in Budapest. Ironically, the Russian spy, after establishing ties with a Hungarian far-right leader who harbored, among others, anti-Slovak sentiments, was then reassigned to work in Slovakia.

Slovakia’s Ministry of Defense refused to comment while the Hungarian Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office and the Russian Embassy in Bratislava did not react at all to our comment requests.

From the Far East to Central Eastern Europe

Born in 1983 in a small village in the Saratov region, a young Anton Gennadyevich Goriev joined the Russian army in the early 2000s. According to VSquare partner Dossier Center’s research, by 2007, at the age of 24, Goriev was already a commander of the division at Russian military unit 49555. This unit, the 2357th Separate Battalion of Radio Direction Finding, was one of the GRU’s many electronic warfare units (it seems that this particular unit has since been disbanded).

According to a senior diplomat of a European country with deep knowledge of Russia and the GRU, Goriev’s unit was part of the 51st Army of the Far Eastern Military District, and it was subordinated to the GRU through the district’s intelligence department. The source added that, within the GRU, it was very likely that its Sixth Department in charge of signals intelligence (SIGINT), electronic intelligence (ELINT) and space intelligence was overseeing Goriev’s unit. “Graduates of regular higher military educational institutes serve there. But before they get into the GRU system of SIGINT military units, the cadets undergo special background checks,” the source added, suggesting that these are all more loyal and reliable officers.

Goriev’s home address at the time was next to his electronic warfare unit stationed in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk on the Sakhalin island, Russia’s Far East. Dossier Center also managed to tie Goriev’s wife to the GRU, as Agnia Gorieva once had a Moscow home address registered at a GRU dormitory. (As Goriev’s spouse, Gorieva enjoyed certain diplomatic immunities too, and she was also forced to leave Slovakia last year.)

In August 2007, Goriev’s career took a sudden turn, at least according to publicly available information on his official employment. Dossier Center’s research has found that Goriev started working for the Institute for Macroeconomic Research and then went to work for the Ministry of Education and Science between 2009 and 2012. However, according to the senior European diplomat familiar with the GRU’s internal workings, Goriev must have been chosen to undergo the training necessary to serve abroad under diplomatic cover during these years.

”To become a GRU officer who performs tasks abroad (legally or illegally), officers graduate from the Military Diplomatic Academy in Moscow. This academy requires students who are sought after throughout the Russian Armed Forces,” the European country’s senior diplomat said. According to the source, GRU recruitment officers tasked with searching suitable candidates for diplomatic postings “can find the best and most vetted candidates” within military units subordinated to the GRU, such as SIGINT units or special forces units.

In May 2012, Goriev officially started working for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The first mention of Goriev holding a diplomatic role—as Russian consul to Hungary—is from January 2013. He is mentioned as one of the guests of a photo exhibition at the Hungarian Military Museum in Budapest.

A Google Earth picture of the rooftop of Russian embassy in Hungary. Source: Vsquare

Hungary’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade refused our freedom of information request on Russian diplomatic postings in Hungary over the past decade. Their argument for the refusal included the protection of Russian diplomats’ privacy and personal data. Although we do not have the exact time of the start of Goriev’s diplomatic accreditation in Budapest, previous versions of the Hungarian ministry’s database of diplomats suggest he very likely arrived after March 2012 and before January 2013.

A former Hungarian counterintelligence officer, speaking under the condition of anonymity, further confirmed Goriev’s GRU affiliation, and provided additional details. The source admitted that Goriev’s spying activity for the GRU was detected both by Hungary’s military and civilian counterintelligence. “Like many of his fellow GRU officers at the Budapest Embassy, Anton Goriev started out in minor operation support roles in the early 2010s. Instead of handling agents himself, he assisted more senior GRU agents’ work,” the former Hungarian counterintelligence officer said. One of his activities included the maintenance of Soviet military graves from World War II, which is a typical responsibility of the GRU.

“This activity involves a lot of traveling to the countryside, which gives GRU officers an excellent opportunity for operational support work. For example, to search the countryside, hike in the woods trying to find suitable hidden locations for so-called dead letter boxes, where GRU assets can drop or receive money, or information. Or to identify safe spots for meetings with those GRU-run agents,” the source added.

”This type of reconnaissance also helps the work of illegal [or deep cover] spies,” the source said, adding that, under the guise of war grave maintenance, Goriev visited many public cemeteries. During such visits, GRU officers not only lay wreaths but also look out for local graves which seem unattended and uncared for, the former counterintelligence officer explained. Graves that are not visited by anyone suggest that no relatives are alive, hence family names could more safely be used to forge false identities that can later be used in the operation of illegal spies.

From the Far-Left to the Far-Right

Visiting WWII memorials and cemeteries of Soviet soldiers also provided an opportunity for Goriev to meet and network with traditionally pro-Russian Hungarian organizations. In 1945, Nazis and the Nazi allies running Hungary were crushed by the Soviet Red Army, paving the way for the country’s 44-years long Soviet occupation. The events of 1945 are still hailed as Hungary’s “liberation” by both Russia and the Hungarian far-left, who regularly celebrate and lay wreaths together. According to a source with ties to the Hungarian far-left, Goriev befriended some among their ranks.

Soviet military cemetery, Székesfehérvár, Hungary, 2015 r. Source: Globetrotter19 / Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0

In January 2015, Hungarian pro-Kremlin far-left organizations joined forces with far-right groups to host an anti-Ukraine gathering. These more than a dozen fringe organizations accepted a common statement requesting “peace” in Ukraine and proclaimed support for Viktor Orbán’s pro-Russian foreign policy. According to their statement, they “proposed that the Hungarian government’s ‘pivot to the East’ policy should be raised to a European level, that NATO and the EU’s hostility to the East should be reviewed and that a system of equal cooperation with Russia should be established.”

While the official statement on the gathering, titled “Civilians want peace in Europe mediated by Budapest—Consultation with Russian participation,” disclosed only that a consul from the Russian Embassy was present, another report identified him as Anton Goriev. Endre Simó, the event’s main organizer, told VSquare that they don’t keep records of the participants’ names and hence he could not confirm it was Goriev who attended. “As it was open to the public, anyone was welcome to attend. The Russian consul presumably attended because he was interested,” Simó added. He did not reply to our questions on whether they had more extensive cooperation with Goriev.

Simó’s organization, the Community for Peace of Hungary (Magyar Békekör), which hosted the conference, is a well-known pro-Russian far-left group founded in 2014 ”to voice the Hungarian people’s desire for peace in the midst of the Ukrainian crisis.” Besides bashing Ukraine, the group was also busy ”conducting civil diplomacy against the deployment of US heavy weapons and NATO forces in Hungary, lest they turn our country into a staging ground and engage our country in war against Russia.”

What made this 2015 conference more significant was the presence of far-right groups, such as the World Federation of Hungarians (Magyarok Világszövetsége), a revisionist group originally founded just before WWII. The Federation was the driving force behind a failed public referendum in 2004 to issue dual citizenship en masse to the Hungarian ethnic minority living in neighboring Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Serbia (dual citizenship for ethnic Hungarians has been introduced by Viktor Orbán’s government in 2010 eventually).

The anti-Ukrainian common statement from the Community for Peace of Hungary’s event portrayed the Ukrainian government as extremely hostile towards the local Hungarian minority. “The 16 organizations protested against Kiev’s plan to send 3,000 Transcarpathian Hungarians aged between 20 and 60 to the Eastern Front and use them as ‘cannon fodder’ against the Russian population. They rejected Kiev’s plan to deprive Hungarians in Transcarpathia of dual citizenship,” the official report on the conference summed up. A picture of the event shows World Federation of Hungarians vice-chairman Zoltán Bottyán holding a banner with the following text: “Do not take the young Hungarians of Transcarpathia as cannon fodder in the conflicts in Ukraine!” This fringe gathering even received mainstream media coverage. Rightwing news channel Hír TV focused on the fact that the organizers had actually ”published a statement supporting the foreign policy of the Orbán government.”

Goriev received a promotion during these months. While the report on the anti-Ukrainian gathering still mentions his position as consul, a few months later, in April, Goriev had a new title next to his name: second secretary and head of the Russian Embassy’s consular section. At that time, he was an invited speaker at an event on possibilities for Hungarian students to study abroad at Russian universities. In the mid-2010s, not only the foreign ministry but also the Russian Ministry of Education officially employed Goriev from time to time.

On April 30, 2015, when the infamous Russian “Night Wolves” biker gang visited Hungary, Goriev was busy again. “The Russian Embassy in Hungary helped us with everything concerning the organization of the rally in that country,” a Night Wolves gang member was quoted as saying. According to the report, the Russian Embassy’s staff not only helped organize but also participated—Goriev included—in the pro-Putin Night Wolves’ wreath laying ceremony at a Budapest cemetery. The local memorial to some five thousand Soviet soldiers had been opened by Vladimir Putin during his February 2015 visit to Budapest.

Anton Goriev in Ásotthalom, Southern Hungary, 2016. Source: YouTube screenshot

A year later, on April 12, 2016, Goriev had yet another public appearance alongside a well-known Hungarian extremist. He was invited to a small ceremony in the village of Ásotthalom in Southern Hungary, where an obelisk honoring Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin was unveiled amidst speeches praising Russia. The village was run at the time by mayor László Toroczkai, then vice-chairman of the far-right and pro-Russian Jobbik party, who is currently chairman of the even more radical Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) party.

An analysis by Hungarian experts Péter Krekó and Lóránt Győri for the Atlantic Council highlighted the Goriev-Toroczkai meeting as an example of how Russian diplomacy is building ties with the far-right in Central Eastern Europe. They highlighted that Toroczkai’s political movement, the revisionist Sixty-Four County Youth Movement (HVIM), ”has been engaged in extremist recruitment activity beyond the country’s borders; it also released statements claiming that “Transcarpathia is not part of Ukraine,” organized protests in support of the Donetsk People’s Republic, and called for the boycott of chocolates produced by Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko’s company Roshen.”

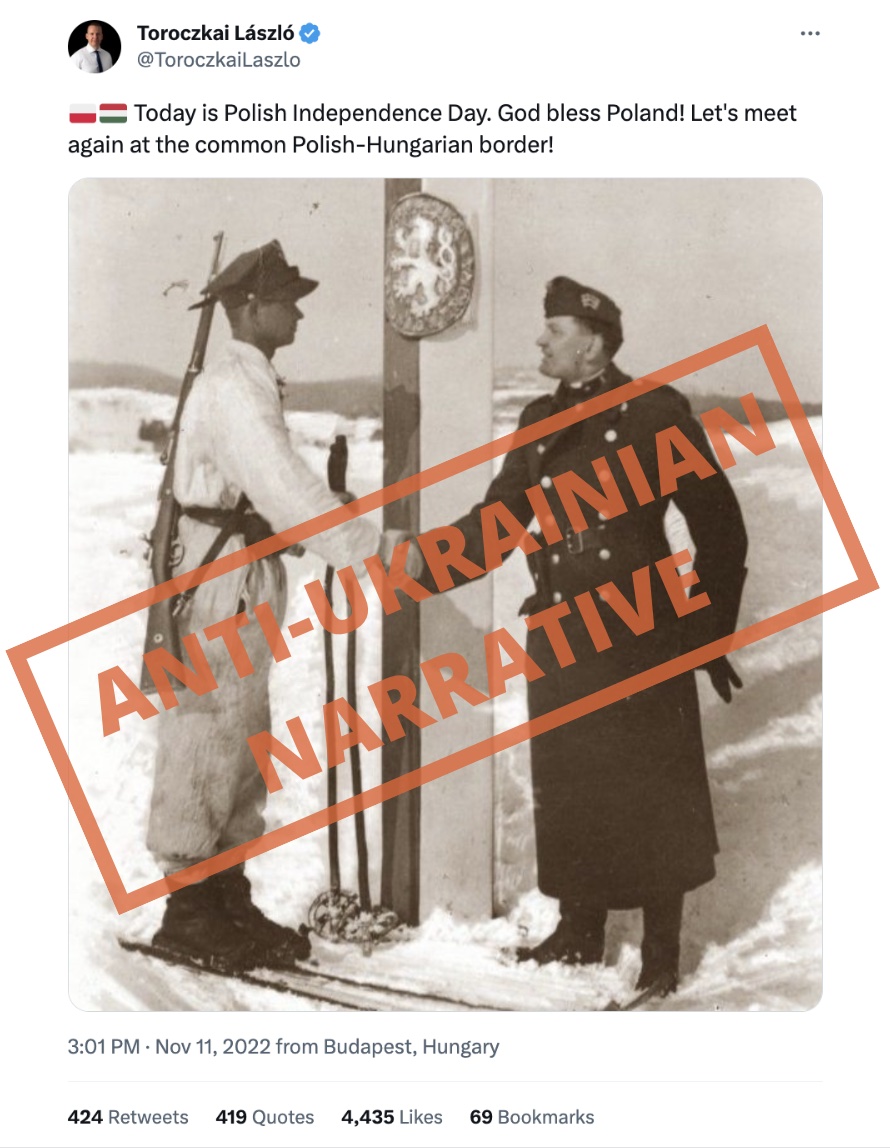

Toroczkai’s anti-Ukrainian views received more international coverage recently, when, on November 11, 2022, he posted a historic photo from 1939 of Hungarian and Polish soldiers shaking hands. “Today is Polish Independence Day. God bless Poland! Let’s meet again at the common Polish-Hungarian border,” Toroczkai wrote, allegging that Ukraine and Slovakia should be partitioned by the two countries. His tweet was quickly condemned by Ukrainian officials.

Screenshot of Twitter post

In a reply to VSquare, Toroczkai denied he knew Anton Goriev at all, or that the Russian diplomat had any role in organizing the Yuri Gagarin celebration years ago. Toroczkai wrote to VSquare that he only sent a general invitation to the Russian Embassy for the event, and it was them who sent Goriev. “I would have been most happy for the Russian ambassador [to participate], but unfortunately he didn’t come,” Toroczkai added.

From Budapest to Bratislava

There is no explanation why Goriev, who was officially consul and then head of the Russian Embassy’s consular section in Budapest, was sent to events seemingly unrelated to regular consular work. However, Goriev’s consular section itself was involved in some extraordinary cases.

In November 2016, Hungarian authorities raided a weapons warehouse just outside of Budapest and detained a pair of Russian arms dealers as part of an international investigation led by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The arms dealers, Vladimir Lyubishin Sr. and Jr., were stinged by undercover DEA agents who posed as Mexican drug cartel members. The Lyubishins agreed to sell old Soviet weapons discarded by the Hungarian Defence Forces to the cartel, in return for cocaine and millions of dollars (the story was uncovered by Direkt36).

After the Lyubishins’ 2016 arrest, however, the Goriev-led consular section of the Russian Embassy in Budapest instantly got involved in an attempt to evacuate them. Consular staff regularly visited the arms dealers in prison and sat in during all their court hearings, according to a source close to the Lyubishins. Eventually, Russia managed to save the arms dealers from U.S. extradition by staging a fake FSB investigation, based on which they submitted their own extradition claim to Hungary for the arms dealers.

Upsetting his U.S. allies, Orbán’s government favored this made-up Russian extradition request over that of the Americans. Soon after their extradition to Moscow in 2018, the Lyubishins were set free. The U.S. State Department denounced the events in a strongly worded statement, claiming that “this decision raises questions about Hungary’s commitment to law enforcement cooperation. This decision […] will make citizens in the United States, Hungary, and the world less safe.”

We could not find any publicly available reports on Goriev’s activities in Hungary from the following years. But we do know that Goriev appeared on the Slovak Foreign Ministry’s list of accredited diplomats in January 2020, according to a list we have in our possession. Strangely, however, Goriev’s name also remained in the Hungarian MFA’s database until as late as November 2022. Hungary’s MFA ignored our request for clarification. However, a senior diplomat of a NATO country suggested that the Hungarian database was outdated, and they simply forgot to delete Goriev’s name from the list. Because of that, we do not know when exactly he received his new diplomatic posting in Bratislava.

In August 2020, a Russian investigative journalist wrote in a VK post that Goriev was among the three Russian diplomats expelled from Bratislava in connection with the 2019 murder of a former Chechen rebel in Berlin. The VK post identified Goriev as a GRU colonel, and mentioned that he had “already spied in Hungary” before Slovakia. However, the main information relating to Goriev’s expulsion was not true, as was proven by both later Slovak foreign ministry diplomatic lists which still included Goriev’s name, as well as his 2021 drunk driving incident—Goriev’s only public mention in Slovak news.

Anton Goriev’s eventual expulsion happened after Russia’s attack on Ukraine in spring 2022, based on our research of the Slovak foreign ministry’s diplomatic lists. For example, his name was on lists from late 2021 but it went missing from a post-expulsion diplomatic list from May 2022.

Side entrance to the Russian Embassy in Bratislava. Source: VSquare

In fact, there were two rounds of expulsion of Russian diplomats in March 2022. In the first one in mid-March, Slovak authorities uncovered an alleged Russian spy ring run by staff of the Russian Embassy in Bratislava. Police have charged Pavel Bučka, a retired employee of the Ministry of Defense of the Slovak Republic and former vice chancellor of a military academy in Liptovský Mikuláš, among others. In his testimony before the judge, Bučka admitted that he had been providing sensitive information to Russian contacts since 2013, meeting his handlers in hidden locations and leaving SD memory cards in so-called dead letter boxes. His Russian contacts remained unnamed in the court documents.

The second round of expulsions came in late March, when Slovakia halved the number of Russian embassy staff and kicked out 35 diplomats. “In the case of Russian embassies, almost 100 percent, really, every single person who is in Slovakia is originally an intelligence operative who only has a diplomatic cover,” then-defense minister Jaroslav Naď told ICJK.sk for our previous #ESPIOMATS story.

The fact that Goriev had been reassigned from Hungary to neighboring Slovakia raises another suspicion: that he has long been involved in covert operations on both sides of the Slovak-Hungarian border. It is also remarkable that certain far-right radicals with whom Goriev was in contact with during his years in Hungary—like Toroczkai—were explicitly anti-Slovak. According to Ferenc Katrein, former director of operations at Hungary’s Constitution Protection Office (AH), such cross-border activities of Russian spies are common. “They may not even be used for operations in the country to which they are accredited [as diplomats]. Some of the best spies are used in a third country. That is why cooperation between counterintelligence services of allied countries is necessary,” the former counterintelligence officer told VSquare.

Katrein believes that Goriev’s activity must have been primarily hurting Slovakia’s national security interests. “I don’t think that Slovakia would be the first country to ban an identified intelligence officer who is accredited in their country, but actually works in Hungary. After all, Slovakia is taking on this conflict with Russia, and the so-called mirror reaction [Russia retaliating by banning the same number of diplomats] will be to the detriment of Slovak diplomats. It is in your own self-interest to send away the people who hurt you the most,” Katreid added.

Péter Krekó, the first to write about Goriev’s ties to far-right radicals, was not surprised at all to learn about his undercover work for the GRU. “Russia’s military intelligence service has in recent years usually played a prominent role in active measures aimed not only at espionage but also at spectacular destabilization of Western institutions,” he told VSquare. According to him, Goriev’s story is a good illustration of how Slovak security agencies are much more active in countering Russian influence than the Hungarian authorities. From Budapest, not a single Russian diplomat has been expelled in recent years, not even after Russia’s invasion. “However, it is not self-evident that Slovakia is so active, as Slovak public opinion is traditionally much more pro-Russian,” Krekó added.

Our online research on Goriev’s more recent activities since his expulsion from Slovakia last year did not provide any results, apart from Dossier Center’s finding that Goriev was still employed by the Russian foreign ministry in December 2022. We don’t know about his current whereabouts, and neither Anton Goriev nor his wife Agnia reacted to our emails sent to private addresses they allegedly used in the past.

Contributors: Anastasiia Morozova/FRONTSTORY.PL, Tomáš Madleňák, Lukáš Diko/ICJK, Dossier Center

#ESPIOMATS is a cross-border investigative project lead by VSquare

#ESPIOMATS is a cross-border investigative project lead by VSquare

in collaboration with journalists from Delfi, De Tijd, Dossier, Expressen,

Frontstory, ICJK, and LRT.

VSquare’s Budapest-based lead investigative editor in charge of Central European investigations, Szabolcs Panyi is also a Hungarian investigative journalist at Direkt36. He covers national security, foreign policy, and Russian and Chinese influence. He was a European Press Prize finalist in 2018 and 2021.