Although the Chinese offer for Central and Eastern Europe remains mainly at the declaratory stage, the situation of Chinese investments has changed radically in recent years. Until now, the main instrument of Beijing’s “divide and rule” policy in the EU have been bilateral relations with the three regional powers (Germany, France and the United Kingdom). But a regional 16+1 format, which brings together China and sixteen Central and Eastern European countries, became a new tool for exerting influence on the continent’s economy.

The 16+1 format is supposed to convince smaller countries to cooperate with China. It is also very controversial in Western European countries – considered to be a side door by which China tries to get into Europe and implement an investment financing offer – one that doesn’t follow EU regulations on tenders and state aid. The fact that Central and Eastern Europe is a genuine gateway to Europe via road and rail routes from Asia to the continent is visible and significant in this strategy.

Beijing’s policy in a nutshell: China wants open markets but closes its own market to external investors. The pattern is simple: create a company with us, transfer your technology and we will provide unlimited funding for the project. The European Union is currently treated primarily as a market and a source of advanced technologies. Beijing’s policy focuses on maintaining the status quo: asymmetric opening to Chinese exports and China’s takeover of European companies.

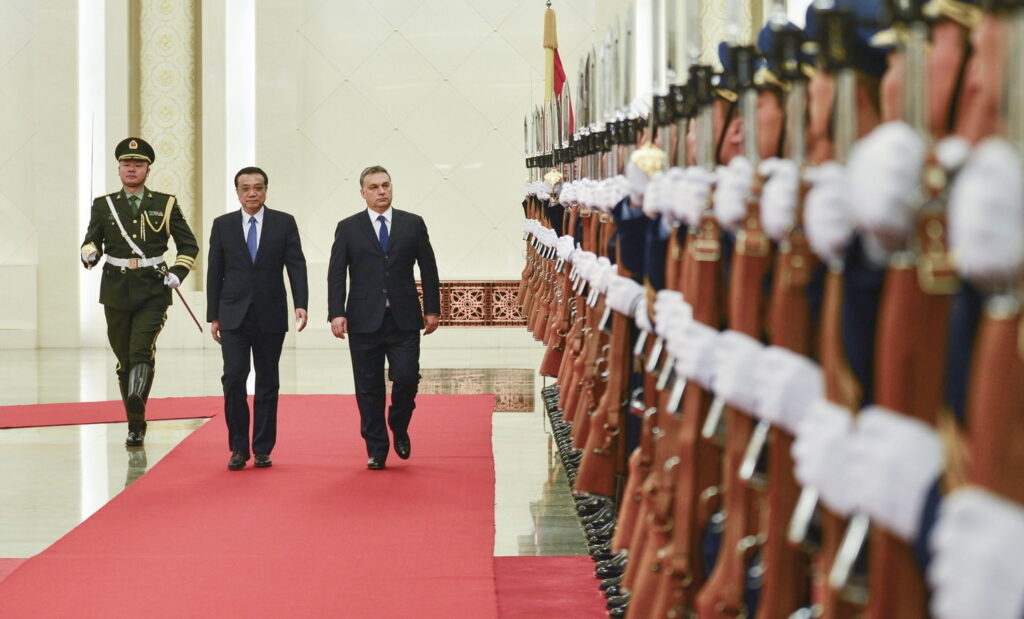

How do Visegrad countries react? Hungary has adopted a strategy to promote Chinese interests in anticipation of bilateral economic benefits. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban boasts good relations with China and the success of his Eastern opening policy. He often responds to criticism from Brussels, mentioning his new rich and non-liberal friends who want to help him out in domestic economy. However, China may not be willing to help, as shown by planned infrastructure projects and promised loans that have never materialized. The reason? Beijing and Budapest have completely different expectations. Hungary does not have the industry that China needs and the Hungarian market is too small for Chinese investors. Chinese businessmen often complain about the “expectations” of Hungarian politicians for bribes.

Despite all this, Orban probably overestimates the importance of China’s role in the Hungarian economy. Government statements give the impression that Beijing will be the saviour of the Hungarian economy, thus creating unjustified expectations. But at least one huge Chinese project could finally materialize in Hungary and could be pushed through simply to provoke Brussels: the redevelopment of the Hungarian section of the Budapest-Belgrade railway worth 2.47 billion euros. This investment would be the first Chinese infrastructure project on such a scale in the European Union. Beijing has already bought the port of Piraeus in Greece and needs a railway line to transport goods to the heart of Europe. There is one but significant problem: the investment would pay back for itself in… 2400 years’ time.

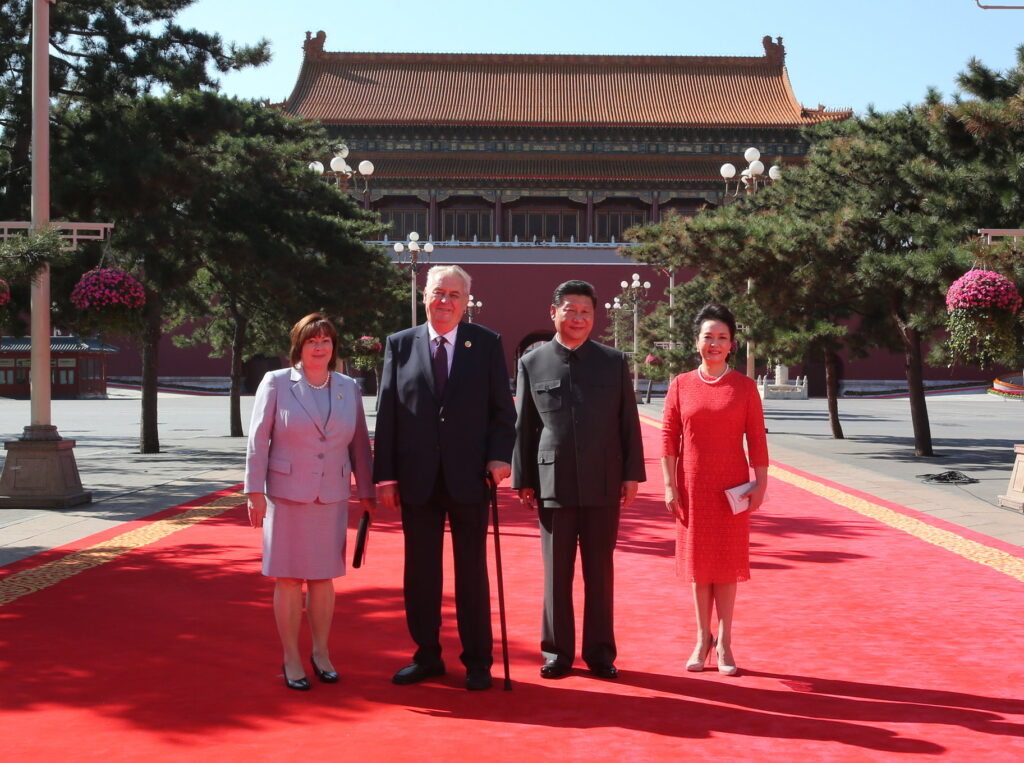

In recent years, China’s state-owned banks Bank of China (BoC) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) have entered the Czech market. A private Chinese company, CEFC, acquired shares in Czech state-owned airlines, majority stakes in the Pivovary Lobkowicz brewery and the football club Slavia Praga. Former Czech President Vaclav Havel, who died in 2011, supported Chinese dissidents and the self-determination of Tibet and hosted the Dalai Lama many times in Prague, but such gestures are now unthinkable. The current Czech President Miloš Zeman appointed CEFC President Ye Jianmingh as his economic advisor. During China President Xi Jing’s visit to Prague the Czech police cleaned up the meeting area of pro-Tibetan demonstrations. Zeman is also the only EU leader who appeared at the great military parade in Beijing on the anniversary of the end of the Second World War two years ago.

The world-famous CEFC (China Energy Company Limited) has become a major Chinese player in Czech investments. CEFC CEO Ye Jianming was appointed as a Special Adviser on Economic, Diplomatic and Investment Affairs of China by the Czech President in April 2015 and became the first Chinese presidential advisor to a European country. After Ye Jianming was appointed advisor to Miloš Zeman, CEFC announced that its European headquarters would be located in Prague. Ye Jianming is an interesting figure: he has bought a 15% stake in Rosneft, the state-owned Russian oil giant for $9 billion.

In Chinese investments in the Czech Republic an active role is played by Jaroslav Tvrdík, former Minister of Defence (2001-2003) and former President of Czech Airlines (2004). In 2016, under his guidance, CEFC bought shares in Travel Service company (50%) and two hotels: Le Palais Art Hotel Prague and Mandarin Oriental Prague. Other investments include the luxurious Prague complex Florentinum, which previously belonged to Penta Investments Limited.

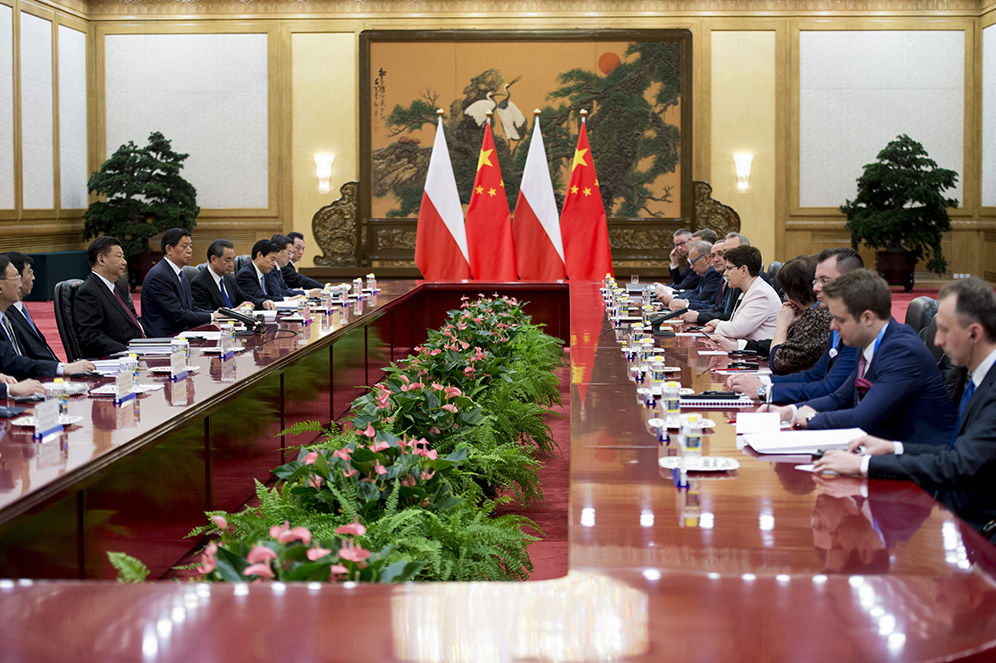

Poland sends to China goods worth almost two billion euros – only 1 percent of all Polish exports. In turn, the Chinese flood the European country with goods worth twelve times more (China is the second largest supplier of goods to Poland, after Germany). From an economic point of view, China is a threat.

The ruling Law and Justice party has been counting on partnership with China since the beginning of its parliamentary term. Why? According to politicians close to the Polish government with whom we spoke, counting on the Chinese is a kind of tradition, a Polish specialty. A few years ago, work on the Polish motorway was undertaken by a Chinese company Covec, which left the construction site in a mess and escaped from Poland. It was only after a few years that an agreement between Covec and the Polish government was reached, without publicity.

An important politician of the ruling party says: “We were supposed to get a great and cheap highway, and it ended in shame. The road to Warsaw has been completed by another company and the deadlines have been extended. This project left a nasty aftertaste. Faith in the Chinese continues. New projects are still being born, in which the Chinese would play a significant role. These are concepts such as: ‘Let’s allow Chinese airlines to take over LOT Polish Airlines and conquer the world together’, ‘let’s let the Chinese build super-fast railways’ or ‘let the Chinese build a car factory”.

One of the Polish experts on China says: “I was recently amused by an article entitled ‘The Chinese are building an electric car factory near Zgorzelec’. The article states that a factory can actually be built, but near Görlitz, on the German side of the border. Maybe the inhabitants of Zgorzelec will find a job there, but the factory will be German, because the electric car market is in Germany and not in Poland”.

According to experts, Chinese expectations towards Budapest and Warsaw are like a pendulum. First, they wanted Budapest to become a Chinese hub for Europe, and then Poland. It is characteristic that China expected that Poland would change its public procurement law for their investments. But there are EU rules that cannot be changed, so the talks are at a standstill.

Experts claim that Poland is too small a country, too small a player and too small a market for China to establish special economic relations with and make Poland a “gateway to Europe”. In addition, newcomers from Asia are aware of the political context: the EU does not like China’s monopolistic tricks and dumping practices (eg. in the steel industry). It is therefore important that China maintains good relations with the EU’s most important players. In this game, Poland is doomed to stay on the periphery for the time being.

From our sources close to the government, it appears that there is one figure in the circles of the Polish Prime Minister, who is extremely active in Chinese affairs. He is Marek Suski, an outstanding representative of Law and Justice, one of the most important people in the government over the past several months – he is the head of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki’s political cabinet. He is an amateur painter, make-up artist and wig-maker by education. He supports Chinese investments unofficially, but there is one problem: Suski is a politician, he has no idea about China or business.

An expert who knows Polish-Chinese relations says: “Suski is the key person in Prime Minister’s circles responsible for Chinese affairs. He is an amateur. He has been fascinated by China for several years, attending meetings, conferences, and even has contacts in the Chinese Communist Party. He has brought Chinese businessmen here, recently he brought a team that wants to build an amusement park. A year earlier, I had seen Suski on a plane to Budapest going for a 16+1 meeting with several businessmen. He is a member of the parliamentary group on Polish-Chinese cooperation”.

In 2017 Suski, accompanied by Chinese people, came to Radom, a degraded city located 100 km from Warsaw. He appeared at the side of CEO of Beida Jade Bird company. He presented the company as a potential investor. In which industry? Nobody knows. “They represent a multinational capital group with multi-billion annual revenues”, Suski assured. By a coincidence, Beida Jade Bird World had organized a festival in China, where Suski was a special guest. Not much is known about the company in Poland, apart from the fact that its name appeared in the documents of the Panama Papers scandal.

All members of the Visegrad Group try to build a good climate for cooperation with China in many ways, seeing it as a new “promised land” for the expansion of their companies and an unlimited source of foreign investment. Polish and Czech companies are trying to gain access to the Chinese market, but for the time being imports are much higher than exports (in the case of Poland – as many as ten times). There is also a political problem: the Chinese authorities are openly opposed to constitutional democracy, which the recently appointed new head of the central propaganda department, Huang Kunming, described as one of the ‘wrong theories’ of the West.

In Slovakia, Chinese companies invest in warehouse space. In September 2017 the Dutch logistics giant Prologis announced the sale of its largest assets in Slovakia to a Chinese company. The purchase price was not announced and there were no reasons why Prologis decided to sell it. The warehouses near Galanta in Slovakia cover an area of 240,000 square metres – today they are owned by four Slovak companies which belong to the Chinese state-owned enterprise CNIC Corp. According to their accounting records, their total assets are worth a total of 94 million euro. Strikingly, none of the companies with multi-million assets has any legal representatives in Slovakia. In October 2017, managers from all four companies resigned and the positions have been empty since then.

From the point of view of the Visegrad Group countries, the character of Chinese investments in the region focuses mainly on the acquisition of existing entities. This raises additional concerns about the drainage of new technologies. Construction of production plants from scratch and creating new jobs are rare. Despite objections, the Visegrad Group countries are stubbornly betting on China – and vice versa.

China’s direct investment in Central Europe is still small compared to, for example, Japanese or Korean direct investment, but it is visible and appears to be modelled in a strategic, political way. Vsquare has examined how it looks in the Visegrad region. Are there areas where Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia could join forces in relations with Beijing? Who derives the most economic and political benefits from the presence of the Chinese today? How can one manage the autocratic nature of the Chinese Government, the scontrol of authorities over the banking sector and the ‘crony capitalism’? Is Chinese foreign investment something more than just a purely economic matter of neutral value?

This is the first of series of articles about Chinese investment in Central Europe written by Vsquare journalists