by Karin Kőváry Sólymos, ICJK

Now, more than a month into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the barrage of disinformation about the conflict is intensifying. Pretexts for the war and pro-Kremlin narratives, however, are not being spread by only well-known faces and websites from the Slovak disinformation scene. Among Moscow’s defenders we find QAnon, the conspiracy theory–turned–movement, which until not long ago took little interest in the situation in Ukraine. In collaboration with Infosecurity, an initiative dedicated to fighting disinformation, we examined the pro-Russian narratives that QAnon has been disseminating through different channels, including Telegram, and how it has managed to incorporate the war in Ukraine into its conspiratorial worldview.

The Slovak version of this article was originally published on icjk.sk

A half-naked man, heavily tattooed and wearing a fur hat with horns, holding an American flag, runs through the halls of the US Capitol. It is 6 January 2021. The US Congress has convened to confirm Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election. But angry Donald Trump supporters storm the building in an attempt to disrupt the proceedings.

Jake Angeli, better known as the QAnon shaman, sticks out among the rioters. Cameras even caught him sitting behind the desk of Vice President Mike Pence, who, moments earlier, had been presiding over the joint session of Congress. Agneli left Pence a message on the desk: “It’s only a matter of time. Justice is coming.”

The QAnon shaman became a symbol of the violent protests without most people knowing just what a tangled web of conspiracies QAnon followers believe. Angeli would later regret his actions in court; he is now serving more than three years behind bars. According to Politico, it seems like ex-president Donald Trump might be in trouble as well. A federal judge has ruled that Trump likely committed obstruction of Congress on 6 January 2021.

Since the storming of the Capitol, QAnon has been cropping up everywhere, it seems. The movement all began with a post made to the internet forum 4chan by a mysterious user known as “Q,” who wrote about how the world was ruled by the so-called deep state, a global cabal of satanic elites, paedophiles, and secret services.

But QAnon is not a one-person show. It is a broad international community of supporters who believe in various conspiracy theories. It has followers in Slovakia and Czechia, who have lately become interested in the war in Ukraine. As Bellingcat notes, QAnon is not a “static conspiracy theory” but is constantly evolving and always picking up new elements. Thus, in the past few years the pandemic has found its way into its conspiracy theories, as has the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the past several weeks. Followers have connected the war with older conspiracies.

QAnon in Czechia and Slovakia

QAnon is active in Slovakia, at the very least online. For several years, the movement’s official website was qanon.sk, which was created in September 2017. The Slovak initiative konšpirátori.sk, which monitors disinformation and maintains a database of dubious websites, rated the qanon.sk as highly problematic.

According to the initiative’s assessment of qanon.sk, “the name of the website, as well as the main image on the page, featuring the slogan “WWG1WGA” [“Where we go one, we go all”, the QAnon movement’s popular slogan], is a clear reference to the QAnon conspiracy.” The logo also suggests that the website is aimed at readers in both Slovakia and Czechia.

The landing page of qanon.sk. Source: Wayback Machine

According to data published by SimilarWeb, in February 2022 the page had nearly 53,000 unique visitors. More than half were from Czechia, and another 40 percent from Slovakia. Although the page is still active, it states that “from 13 March 2022 the website qanon.sk is operating under a new domain, vitazstvosvetla.org.” The site has also been renamed “The Victory of Light” (Víťazstvo svetla). This change was made in response to an alleged attack on the movement’s previous website.

The site also claims that the new name “better captures [its] meaning and focus.” But the contents have not changed. The site’s authors, whose identity is unknown, have taken many conspiracy theories and claims directly from the American branch of QAnon: they write about Trump, about child abuse committed by the elites and satanists, about a cabal, about dark forces, and even about extraterrestrial factors in the “illuminati control of the Earth.” In the past, they have published anti-vaccine content on their webpage and social media accounts.

Another major player on the Slovak QAnon scene is the Tadesco website. Like qanon.sk, it also uses the Q logo and the WWG1WGA slogan. This site, however, receives much more traffic. According to data from SimilarWeb, in February 2022 alone the site had more than 720,000 unique visitors. One-third were from Slovakia. In Czechia, the site ranks among the 50 most popular sites in the category of News and Media.

It has special sections dedicated to articles about Russian president Vladimir Putin and Russian “analyst” Valery Pyakin. Based on the contents, it seems this website was pro-Russian long before the war in Ukraine broke out. It refers to the Russian president as “Master Putin,” who will expose the crimes of the illuminati, provide critical information about migration and the coronavirus, and fight side by side with Donald Trump against “the New World Order.”

The momentarily inaccessible website The Rabbit Hole (Králičia nora) also subscribes to the QAnon movement. The Telegram channel associated with this site is also no longer available. It was followed by several thousand users. According to the Wayback Machine, however, shortly before it went offline, this website produced content about Ukraine – it spread an older hoax claiming that Ukraine does not exist.

According to an analysis conducted by Infosecurity.sk, the Slovak branch of QAnon was also active on Facebook, “where it focused not on one specific area but on an entire range of polarizing topics,” including anti-government, anti-masker, anti-lockdown, and anti-vaccination themes. The Facebook pages in question were “QAnon – PREBUDENÉ SLOVENSKO” (QAnon – Awakened Slovakia) and “QAnon – Sk, Cz.” They were later blocked for violating the platform’s community standards – by sharing inappropriate content and spreading disinformation.

There are also Czech and Slovak accounts spreading QAnon conspiracy theories on the VKontakte (VK) social network, which is often called the Russian version of the American Facebook. In contrast to platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, which have developed strategies to stop the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories, VK does not feature such robust moderation. In the past, it did not delete content associated with Nazi symbols or radical far-right ideas. We find several VK accounts subscribing to QAnon with names such as “QANON CZ/SK,” “Great Awakening,” “Donald Trump a vítězství světla” (Donald Trump and the Victory of Light), and “KOB – Koncepce Občanské Bezpečnosti” (Concept of Civil Security). They regularly share articles from well-known disinformation sites and pro-Kremlin channels. Every day, they produce and reshare several dozen posts. Even though VK is not very popular in Slovakia or Czechia, several thousand users in these countries follow the accounts.

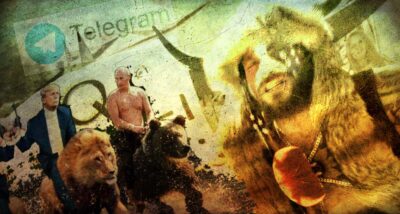

The false information, spread by Moscow, that the maternity and children’s hospital bombed in Mariupol served as a base for the Azov Battalion appeared on the QAnon CZ/SK profile on VKontakte. Source: VKontakte

A change of focus

Unsurprisingly, over the past few years, the Slovak disinformation ecosystem was focused mainly on the COVID-19 pandemic. Frequent topics included various conspiracy theories about the origins of the novel coronavirus and the negative effects of vaccination, as well as the various measures implemented to fight the pandemic. In early 2022, particularly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, these pages shifted their focus to the military conflict raging in Slovakia’s eastern neighbour. Some anti-vaccination channels also changed course. The war in Ukraine has also appeared in groups with some links to the QAnon theory. The tie that binds them all together is that they promote and support an exclusively Russian perspective on the aggression in Ukraine. The disinformation monitoring service Czech Elves (Čestí elfové) has also noted support for Russia across all disinformation channels.

A few days after the beginning of the Russian invasion the qanon.sk website wrote that “two versions of news exist: There is an insider version for the awakened and for those in the Q movement, and there is unbelievably sensational, fear-mongering news from the lame stream because the cabal want to start World War III.”

These sources were already spreading conspiracy theories about “alleged” laboratories in Ukraine run by the United States. They also mentioned the production of “biological weapons” near the Russian border. They describe Ukraine as “the first of many bastions of the New World Order, which must be purged.”

Even though Ukraine became the centre of attention after 24 February (before that most content was about the pandemic and “health”), Slovak websites subscribing to the QAnon theory were already spreading disinformation before the conflict erupted. They connected Russian attempts at “liberating Europe” with conspiracy theories about powerful banking families, such as the Rothschilds and the Rockefellers. They also published texts that accused the USA and NATO of provoking war and spread the Kremlin’s false narrative that Ukraine was created thanks to Russia and the Soviet Union.

Qanon.sk even revealed Russia’s great plan “to return Ukraine to Russia, to restore the Soviet Union, to restore Yugoslavia and to nationalize Russia’s central bank.” Although even before the conflict this site was writing about a “fight,” the day before the invasion’s launch, it claimed, referencing the words of the Russian ambassador to the United States, that Russia would not invade Ukraine.

Even after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, these websites did not stray from the pro-Kremlin line. They claim that it is not a war or an invasion, but a “rescue operation.” We also find vocabulary taken directly from Moscow’s playbook: “Nazis,” “de-Nazification,” and “genocide.” A large number of articles come directly from Russian sources, such as News Front, a Crimea-based media outlet that allegedly collaborates with the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), and anti-speigel.ru.

Telegram, a popular refuge

In October 2020, Facebook announced that it was banning all groups and pages that “represent” QAnon. It was the social media giant’s second attempt at stopping the spread of a movement that the FBI has called a potential domestic terrorism risk. At the same time, though, Facebook’s algorithms played a major role in spreading QAnon content. After the ban went into effect, many people spreading QAnon-related ideas migrated to Telegram, where QAnon-related public channels and group chats have several thousands of subscribers and members.

The false information, spread by Moscow, that the maternity and children’s hospital bombed in Mariupol served as a base for the Azov Battalion appeared on the QAnon CZ/SK profile on VKontakte. Source: VKontakte

Like the main websites spreading QAnon news, these related Telegram channels quickly shifted their focus. They either share pro-Kremlin and pro-Russian narratives about the reasons for and “necessity” of the war or try to connect the current situation with older conspiracy theories. Looking for information about the real impacts of the invasion and Russian aggression would be a futile effort.

In our examination of QAnon channels we found a peculiar line of disinformation pointing to a specific link between Ukraine and “deep state” representatives. The “deep state” is a concept central to the QAnon conspiracy theory. QAnon followers use the term deep state to refer to what they believe to be a “shadow government” ruled by politicians and influential businesspeople. They see it as a conspiracy of a global satanist elite, of paedophiles who operate a global network aimed at forcing children to have sex. According to the movement’s mythology, in 2016 humanity was sent a saviour in the form of US president Donald Trump. Trump currently appears in QAnon’s messaging as a comrade-in-arms with Vladimir Putin in the fight against the elite.

A photomontage shared on a QAnon-related channel in Slovakia. Source: Telegram/Víťazstvo svetla

As Denník N reports, a popular rhetorical device used in the disinformation ecosystem and by Kremlin supporters is “whataboutism.” In this case, it involves turning the tables on people who criticize Russia’s actions by asking about past US military operations or the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in the late 1990s. Telegram channels and public chats are filled with such arguments.

QAnon followers have even found a “connection” between the “provoked” war in Ukraine and vaccinations, which according to authors writing for Víťazstvo svetla is the reason for “the profound difference in perceiving what is happening and what is being presented.” This claim reached 7,000 Telegram users.

QAnon-related Telegram accounts also take texts and unfounded, false claims from anonymous Facebook profiles. QAnon supporters consider the “debunked” news and photographs presented by the mainstream media as “the lies on which the American deep state stands.”

One of the most widespread hoaxes on Telegram was about alleged US-funded biolabs in Ukraine. Even though this piece of disinformation only began to spread rapidly a few days after the Russian invasion, a map depicting the location of these alleged labs was published on the Red Pill (Červená pilulka) channel in late January.

Kremlin propaganda about Ukraine often borrows World War II–era terminology: things in Ukraine are often described as being “fascist,” “Nazi,” or “neo-Nazi.” Back in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, pro-Kremlin media accused the new Ukrainian government of being “ruled by neo-Nazis.” Such vocabulary can be found not only on the above-mentioned websites but also on disinformation-spreading Telegram channels, including those associated with QAnon.

We can also identify QAnon narratives in content shared on other channels, such as S4-illuminati or Absurdni svet (Absurd World). The number of subscribers to the latter have doubled since the war started. But we have not seen this trend everywhere.

Source: Telemetr.io

Slovak conspiracy theorists and extremists on Telegram

In recent years, Telegram has become a hotbed of extremist and conspiracy groups, including ones from Slovakia. There is no precise data about how many Slovaks and Czechs use this messaging service. The Reuters Institute estimates that approximately 3 percent of the European internet population uses it, but it is growing rapidly. The number of Czech and Slovak public channels and chats is indeed slowly increasing. As we have reported earlier, some even have tens of thousands followers.

The chief editor of Infosecurity.sk, Matej Spišák, says that problematic profiles have migrated to Telegram due to that messaging service’s weak to non-existent content moderation, which means that unlike on classic social networking sites, the “survival” of these channels and groups is not at risk. “Classic social networks like Facebook and Instagram have in the past taken action against them by deleting posts or blocking profiles,” adds Spišák.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that disinformation websites, which had problems with Facebook in the past, use Telegram to spread their content. The most famous Slovak disinformation websites have Telegram accounts, including Slobodný vysielač [Free Radio] and four sites recently shut down by the Slovak Security Authority, Hlavné správy (Headline News), Armádny magazín (Army Magazine) Hlavný denník (Main Journal), and InfoVojna (InfoWar).

According to IT specialist and ethical hacker Pavol Lupták, it is technically possible to moderate content on Telegram. Most of the regular messages sent via this app are not end-to-end encrypted. “In practice, this means that much of the communication sent via this app can be seen by the service providers,” says Lupták. Compared to other platforms, however, moderation is extremely lax.

Cover illustration: ORF, Telegram/Víťazstvo svetla, ICJK

Support independent investigative journalism in Slovakia,

Support independent investigative journalism in Slovakia,

you can donate here.