Cover photo: Shutterstock

Illustrations: Sanja Pantic/BIRN 2025-06-12

Cover photo: Shutterstock

Illustrations: Sanja Pantic/BIRN 2025-06-12

A Czech investigation found that a factory owned by the billionaire former prime minister, Andrej Babiš, should have been the prime suspect in an environmental disaster. But the prosecutors and courts looked elsewhere.

In a September afternoon five years ago, along a quiet stretch of the Becva river in the foothills of the Moravian mountains, the fish started acting strange. Stanislav Pernicky heard about it on the phone and hurried over to see for himself. The fish were everywhere, leaping from the river and thrashing about on the shore. “It was as if the water was boiling,” he said, when I tracked him down a couple of days later. “Hundreds of dead fish wherever you looked, others dying in our hands. It’s not a sight I’ll easily forget.”

Pernicky is in his seventies, an economist by background, and he has fished in the Becva for as long as he can remember. The river – its name is pronounced “baitch-va” – is a tributary of the Morava, which feeds the Danube. Pernicky is the chair of the local Fishermen’s Association, a stalwart of Czech country life that oversees all manner of fishing-related concerns, from issuing permits and organising competitions to lobbying officialdom and flagging up illegal spills and dumping. Most of the fishing here is for sport: the catch is returned, alive, to the water. This stretch of the Becva is a home for heavy industry, once powered by the nearby coalfields. Factories built under communism line the river’s banks and discharge their effluent into its waters. The anglers here have always assumed that the fish are unfit for the table.

Watching from the riverbank on September 20, 2020, Pernicky noted young fish among the dead and dying, as well as adults of reproductive age. He was surprised by the sheer diversity of species. “There were barbel, pike, chub, nase, rainbow and brown trout, perch, burbot. It was only then that we realised how rich the river was.” By evening, the scale of the die-off had become evident. All aquatic life had been wiped out along a 40-km stretch of the river. Photos from the day showed men in waders shovelling great heaps of dead fish onto trailers. Between 80-100,000 fish were estimated to have died. The total weight of the carcasses brought ashore was some 40 tonnes.

The disaster made national headlines and shone an uncomfortable spotlight on the prime minister at the time, the billionaire Andrej Babiš. The self-styled “Czech Donald Trump” was a year away from a general election, and his ratings had just nosedived because of his chaotic Covid policy. Now, social media was flooded with speculation that one of his factories had poisoned the river.

Babiš’ Agrofert conglomerate is the country’s biggest employer after Skoda Auto. Its vast holdings include the Deza chemical works, a sprawling site on the banks of Becva that handles coal-tar and petroleum by-products. The spot where the fish began dying off was less than a kilometre downstream from a drain that discharged Deza’s waste-water into the river. In the days after the disaster, the firm’s spokesman became a regular fixture on the TV news, reassuring the country that the factory had nothing to do with the dead fish.

The Czechs used to be lauded as the success story of post-communist Europe, the standard bearers for free markets and liberal democracy. The Becva river poisoning illustrates what went wrong. The disaster would be investigated by journalists and by the authorities. Their diverging conclusions highlight the power of investigative journalism – and its stark limitations – within a compromised system.

Some 40 tonnes of poisoned fish were brought ashore after the disaster. Photos: Stanislav Pernicky; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

I work at Deník Referendum, an online newspaper in Brno, the largest city in the eastern Czech region of Moravia. Our newsroom is less than two hours’ drive from the site of the poisoning. The editor-in-chief, Jakub Patočka, was my co-author for a book about Babiš, and we both have a background in the environmental movement. We began investigating the Becva poisoning, suspecting that there was more to it than met the eye. The breakthrough came with a tip-off from a whistleblower. Our investigation would establish that there had been an industrial accident at Deza, just hours before the fish began dying off. A toxic slew had leaked into the drains on site. We gathered whistleblower testimony and expert analysis to reveal the cause: a combination of human error and long-term neglect. Our revelations were picked up by the national press and broke the traffic records for our website.

Babiš responded by threatening legal action and calling our newsroom a “cesspit of liars”. When he went on to lose the 2021 election, he would blame it partly on the Becva investigation. He seemed to have taken issue with investigative journalists generally – the international consortium behind the Pandora Papers also featured on his list. On the eve of the elections, they had revealed how the prime minister had used offshore tax havens to buy luxury property in France.

While Babiš railed against the watchdog press, he had little to fear from the institutions that could really hurt him – the regulators, police and judiciary. The two-year investigation by the authorities steered clear of his factory. Our reporting had established that there had been an industrial accident at Deza which had led to a toxic leak – but we could not prove that the toxins had reached the river. A Deza spokesperson, responding to our story, insisted that the leak had been contained on site.

However, the institutions that could have established the truth never treated Deza as a suspect. Instead, the prosecution argued that the toxic slew had entered the river from a factory further away, via a drain some three kilometres upstream from the spot where the fish began dying off. Independent experts told us the prosecution’s theory violated the laws of physics. A parliamentary inquiry concluded that vital evidence – water samples from the river – had either been lost or were never collected on time. A video submitted as evidence by the prosecution ended up undermining its case. Its star witness was overheard on film contradicting his own testimony.

Nonetheless, the court eventually endorsed the prosecution’s version of events. The judge also blocked the possibility of appealing the verdict, by downgrading the case: it would no longer be a matter for the courts but for the environmental regulator. Babiš meanwhile is gearing up for another general election this year. With growing discontent over the current government, our homegrown Trump stands a good chance of imitating his hero’s comeback. As usual, he is projected to win big in “rust belt” areas, such as the northern part of Moravia.

The ecocide on the Becva triggered protests in the region. Photos: Zuzana Vlasata, Jakub Patocka; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

Until recently, the Czechs were believed to have held out against the illiberal, authoritarian politics that have taken root in Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. Granted, the country had problems with corruption but it was also prospering within the EU. Like their eastern neighbours, the Czechs have a new class of billionaires, typically the well-connected members of the old communist elite that had taken over the privatised assets of the ex-communist state. Many Czech billionaires have been welcomed westwards. The country’s top businessmen have acquired ammunition factories in the US, as well as a postal service and power plants in the UK. They generally enjoy a better reputation than their post-Soviet counterparts. In the Western financial press, they are likely to be described in familiar terms, as “tycoons” rather than the more exotic “oligarchs”.

The Czech billionaire class is “pretty much pluralistic” compared to its equivalent in countries like Hungary, said Jiri Pehe, a political scientist and former diplomat who now serves as director of New York University’s Prague campus. “Hungarian oligarchs are happy with one-party rule, which guarantees the benefits they enjoy. The Czech oligarchy, on the other hand, operates in a sort of competitive environment.”

In fledgling democracies, oligarchs can exert significant influence over the state – particularly its enforcement of laws and regulations. This helps to lock in their competitive advantage. In the phenomenon described as “state capture”, politics becomes a means to a commercial end, serving to help businesses cement their grip on the market. The result today is a deeply lopsided relationship between business and politics, corporation and state. “Privatisation was overseen by the weak political parties of the time,” Pehe said. “The new class of super-rich was born through this process. And this class consequently started privatising the parties to make them serve their business needs.”

State capture is increasingly a feature of capitalist systems worldwide. It creates a permissive environment for crimes such as ecocide, and it can obstruct the path to a more sustainable future. “The oligarchs and billionaires that control politics in general are operating in an environment that they themselves helped set up,” Pehe said. “Radical changes and regulations are against their interests. In an era of climate change, state capture acts as a brake on states being able to do any innovative policy.”

Following the Waste

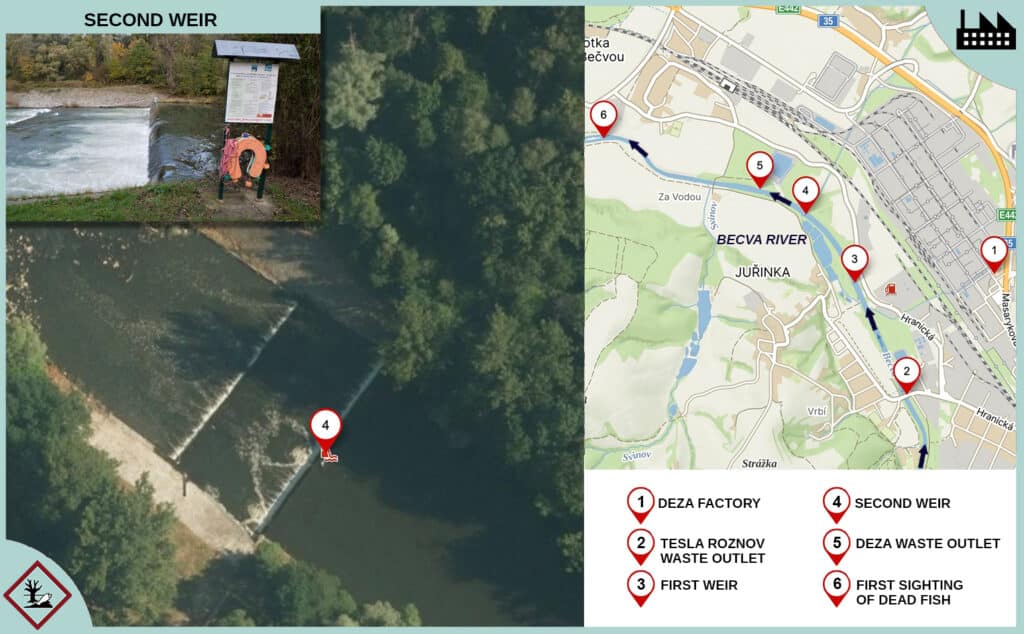

Two weeks after the disaster, I went for a walk along the Becva with Denik Referendum editor Jakub Patočka. We were accompanied by Lukáš Gerla, a local day labourer who knows this area like the back of his hand, having fished here since he was a boy. We began our walk at an unremarkable spot next to a quiet road, where a small bridge crossed the river. Nearby was the waste-water outlet from Tesla Roznov, an industrial site 13 km away that had been declared by the authorities to be the likely source of the toxic leak, shifting suspicion away from Deza.

Along a section of riverbank that had been reinforced with rocks contained behind a wire mesh, we found the outlet from the Tesla Roznov site, an opening no larger than a manhole. Gerla showed us text messages he had exchanged with fishermen who had been on this stretch of the river on the day of the disaster. They did not notice anything unusual. “It makes no sense that poison would have leaked from here without harming the fish,” he said.

Satellite image and roadmap: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

We walked along the river bank from the Tesla Roznov drain towards the zone of the poisoning. Along the way, we passed two weirs or dam-like barriers spanning the breadth of the Becva. More than three kilometres later, we reached the spot where the first dying fish were found. The environmental inspectors dispatched to the scene of the poisoning would have stood here, noting the dead fish everywhere, with the silhouette of the Deza factory visible on the horizon.

If the police were right, the toxic discharge had not come from Deza, less than a kilometre away, but had instead travelled more than three kilometres downstream from the Tesla Roznov outlet before it began killing off the fish. In order to do that, the discharge would have had to stay close to the bank at first, crossing the walls of the two weirs without pooling and dispersing sideways across the width of the river. According to Ivan Holoubek, a leading environmental chemist and former director of Recetox, a research centre affiliated to Brno’s Masaryk University that studies the impact of environmental toxins, the police theory implicating the Tesla Roznov site went “against the laws of physics”.

The police presented Jiri Klicpera, a freelance expert specialising in environmental impact assessments, as its star witness. Klicpera had conducted a series of experiments using a soluble green dye, fluorescein, to model the dispersal of the toxins in the river. Citing his experiments, he would testify that the toxic discharge could have clung to the bank of the Becva as it flowed downstream for more than three kilometres, leaving enough untainted water in the channel for the fish to avoid mass poisoning. It was only at a point three-and-a-half km away that the toxins had dispersed across the river, he argued, killing off large numbers of fish.

But there was a problem with Klicpera’s experiments – they did not support his argument. In footage filmed by the police and played in court, Klicpera poured the green dye into the water at the point where the Tesla Roznov outlet joins the river. The green dye can be seen spreading and mixing evenly between both banks at the point where the first weir spans the river, less than a kilometre from the drain. Klicpera and an accompanying police officer can even be heard offscreen, observing that the dye had fully mixed in the water. If the poison had indeed entered the river at the Tesla Roznov outlet, mimicking the green dye, the mass die-off should have started less than a kilometre away, instead of more than three kilometres downstream.

Satellite image and roadmap: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

Independent experts who conducted similar experiments at the site also said any toxins discharged from the outlet would have dispersed across the river where it encountered the first weir. “There is no longer any area below the weir where the stream is not significantly affected by pollutants,” said a report by Professor Pavel Danihelka, a professor at the University of Ostrava and an expert in environmental hazards.

I interviewed Klicpera over the phone in early 2021, soon after he had conducted the first of his experiments at the site. Photos from the experiment posted on his Facebook account showed the green dye spreading evenly across the river at the first weir, just as it would do in the subsequent experiment filmed by the police. But in the interview, Klicpera maintained that Tesla Roznov was the source of the spill. “Everyone thought the leak had come from Deza, but it wasn’t true,” he said. The fish, he insisted, had simply “got out of the way” of the poison for the first few kilometres downstream. When I pressed him further, he doubled down and suggested that I “did not understand hydraulics”. His other Facebook posts included criticisms of Covid mask mandates and a defence of a notoriously polluting coal-fired power plant.

Even as Klicpera insisted that Tesla Roznov was the culprit, he acknowledged that the evidence was “weak”. In fact, the investigation into the Becva river poisoning had missed the golden window for gathering evidence: the hours immediately after the disaster was reported. The Environmental Inspectorate, a regulatory agency overseen by the Ministry of Environment, was tasked with collecting water samples from the scene. Only two inspectors from the agency visited the site on the day. A third refused to travel because “it was too far away”, according to the parliamentary inquiry into the official response to the disaster. The two inspectors did not take any timely samples along the three-kilometre stretch of river between the Tesla Roznov outlet and the point where the first dead fish were spotted. Nor were any samples taken at the point where the Deza outlet meets the river. “The samples that were taken only prove that the river flows,” said Ivan Holoubek, the environmental chemist.

Nonetheless, the prosecution’s case would be built around a sample from the river. A reading taken from the Tesla Roznov outlet a day after the disaster, on September 21, 2020, would be presented as the proverbial smoking gun. The sample from the drain showed an elevated concentration of cyanide. Both Deza and the Tesla Roznov sites were known to handle cyanide, and were allowed to discharge it into the river at an appropriately diluted level. The legal limit for cyanide at the Tesla Roznov outlet was one milligram per litre; the sample collected at the drain suggested a concentration of nearly 1.70 milligrams per litre.

Satellite image and roadmap: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

However, independent experts questioned the quality of this evidence. The sample taken a day after the toxic leak “did not prove that there was a higher concentration of cyanide on the previous day,” Holoubek said. Moreover, he said, the sample had not been analysed at an accredited laboratory that followed standardised procedures, as preferred by the courts. A 20 percent margin of error should have been taken into account when considering the evidence, but this had not been done. And finally, Holoubek said, the concentration of cyanide shown in the reading was below the level “where it could be considered lethal”.

Holoubek was part of a panel of scientists that challenged the prosecutor’s account. His colleagues on the panel were also highly credentialed experts: Jakub Hruska and Blahoslav Marsalek, both environmental scientists specialising in hydro-chemistry and ecotoxicology respectively. Although the scientists were not admitted as witnesses by the judge, they managed to secure access to data and materials collected by the police. Based on these documents, they concluded that the Tesla Roznov site simply did not process enough cyanide to cause a disaster of the scale seen in the Becva. “We are looking for tens of kilograms of cyanide,” Holoubek said. “And these were just not there.”

During the Cold War, Tesla Roznov had been a hub for Czechoslovakia’s world-class electronics industry. Factories operated by the conglomerate of the same name produced sophisticated radio equipment for the military, as well as radio and TV sets for the consumer market. After the collapse of communism, the conglomerate was broken up and its parts were hived off. The disintegration of labour-intensive industries pushed the surrounding region into economic decline. Today, the site hosts a mix of older industries such as metal-galvanising plants, alongside hi-tech facilities that handle nanofibres and semiconductors.

The site was officially declared a likely source of the toxic spill within a fortnight of the accident. “The noose is tightening,” Environment Minister Richard Brabec said at a dramatic press conference, effectively quashing speculation that the Babiš-owned Deza factory would be considered a suspect. A local firm, Energoaqua, owns and manages the Tesla Roznov site and is responsible for making sure that any toxins are filtered out, or diluted to safe levels, before the waste water enters the river. The police investigation focused on the firm. Officers became regular visitors at Energoaqua’s headquarters, inspecting paperwork and facilities and interrogating the staff.

Satellite image and map: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

In December 2020, the 32-year-old head of the firm’s waste-water treatment facility, Pavel Janota, hanged himself in his apartment. In a public statement, Energoaqua CEO Oldrich Havelka described his employee’s death as a tragedy. “He was a very sensitive man, an introvert who carried everything inside him,” he said. “He probably couldn’t handle the pressure around him, but we don’t know the real reason.”

Energoaqua’s managers denied any link to the Becva river disaster. If found guilty, they could face six years in jail, and a fine of nearly a million euros.

Too Big to Confront

Ten years ago, I was researching what would eventually become a book about Babiš’ business interests, co-authored with the editor, Jakub Patočka. I was struck by the businessman’s reach. His holdings at the time included the country’s largest media company. He had acquired the outlets, he said, so that the press would finally start telling the truth about him. Media was just a small part of a corporate empire spanning multiple sectors. His companies had more than 30,000 people on their payroll; few felt they could openly criticise him. His competitors also watched their words in the presence of journalists, concerned that he may use his political clout to hit them with financial controls.

In a captured state, decision-making at regulatory agencies can be influenced through a handful of senior appointees. “You don’t need to control every single person in the system – just a few people in key positions,” said David Ondráčka, the former director of the Czech branch of Transparency International, the Berlin-based anti-corruption watchdog. Only senior officials at the agencies need be aware that their positions depended on the good graces of a political master. The rest of the people, he said, “are so focused on their immediate tasks, they do not consider the overarching purpose behind what they are doing.” The staff could be biased in their duties without necessarily thinking of themselves as compromised, he said. “They might do their jobs honourably enough, but they would also always respect the fact that some players were untouchable, too big to confront.”

Media outlets owned by Babiš backed the theory implicating Energoaqua. Their coverage drew heavily on a leaked report from the prosecution witness, Jiri Klicpera. Environment Minister Brabec seemed to take a personal interest in the case. At one point, he tweeted that he was rushing to inspect the site himself, following reports that foam had been spotted in the river near the drain. Deza’s representatives initially stuck to the official line, insisting that nothing untoward had happened at the plant. “We have not detected any leak of hazardous substances,” spokesman Karel Hanzelka said, when we contacted him for comment in November 2020.

The evidence would suggest otherwise. A few weeks after the disaster, I had begun communicating with a source who had contacted me via encrypted e-mail, claiming to be a worker at Deza. “I have information,” the messages said. “Do you want to meet?” The source made a sensational claim. An industrial accident had taken place at the factory early on the morning of 20 September 2020, just hours before the disaster, and it had been covered up.

Satellite image and map: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

The accident had occurred in a part of the factory that processed phenol, a byproduct of coal tar. Commonly known as carbolic acid, phenol has a wide range of industrial applications. It is used as a precursor for manufacturing plastics, explosives, nylon, detergent and pharmaceuticals. The processing of phenol at Deza involved another chemical commonly used as a precursor in manufacturing: sodium hydroxide. Also known as caustic soda or lye, sodium hydroxide is used to make soap, wood pulp, paper and textiles. Deza produced its own supply on site, in a vast reactor-like unit featuring an array of industrial vats.

Our reporting established that there had been a fateful combination of human error and technical failures on the overnight shift. A vat in the unit had overheated. This should have triggered an alarm, but the warning system had been disabled by the workers because it tended to activate randomly. Whistleblowers interviewed on condition of anonymity indicated that there had been a culture of cover-ups within the factory, with workers periodically drinking alcohol and falling asleep during shifts. On the night of the accident, the worker monitoring the unit had fallen asleep. Photos of the Deza site showed that the lid of the vat was also improperly sealed: it had been secured by a makeshift fastening, a plank of wood. In the early hours of September 20, some twelve cubic metres of toxic fluids would escape from the malfunctioning vat. Much of it passed down a storm drain, initially undetected.

We published our investigation on November 30, 2020, two months and ten days after the disaster. The traffic almost crashed our website. Babiš was heckled in parliament and went on to describe our newspaper as liars. We sued him over the claim; the case is still being heard. When Deza was confronted with our findings, a spokesperson confirmed that an accident had indeed taken place on the night, contradicting the firm’s narrative. However, the event was described blandly as an “operational incident” that had been followed up within the firm, according to protocol. Deza said an official had checked the waste-water quality after the leak, and recorded nothing noteworthy. “None of the ingredients were toxic and the bulk ended up in containment ponds,” spokesperson Karel Hanzelka said.

We managed to acquire a sample of the substance that had leaked during the accident, and submitted it for analysis. Tests confirmed a high concentration of phenol. Marek Petrivalsky, a biochemist at Palacky University in Olomouc, said the sample also probably contained other toxic substances that could not be automatically identified. Could the disaster have been caused by a toxic mix of phenol and other chemicals, rather than cyanide?

Satellite image and map: Mapy.com; Inset photo: Denik Referendum; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

The fish did not display the classic signs of cyanide poisoning. Witnesses said the animals appeared intensely agitated – very different to the stunned behaviour seen in fish poisoned with cyanide. Nor did the fish develop cherry-coloured gills, another telltale indication of cyanide poisoning. The state’s top veterinary body, a subsidiary of the agriculture ministry, analysed the dead fish but could not prove a conclusive link to any one poison. Moreover, the evidence that could definitively answer that question – timely samples of river water – were never collected from the appropriate locations.

The accident at Deza and the ecocide on the Becva seemed like a remarkable coincidence, but our investigation could not prove a causal link. There was no conclusive proof that the toxic discharge from the plant had entered the river and killed off the fish. But other institutions, with a broader remit, could have picked up where we left off. After publishing our investigation, we offered to co-operate with the police. They could have opened an investigation into Deza and compelled it to release internal memos from the night of the accident – but they did not do so.

In January 2021, several Deza workers were summoned to meetings with the police. The workers assumed they would be questioned about the accident we had reported. However, they said, the officers were more interested in tracing their dealings with the press. Jakub Matocha, a former Deza employee who left the firm in 2022, was alone in being willing to be identified by name. His account was echoed by others who spoke on condition of anonymity. Matocha told me the police had checked if my number had been saved among the contacts on his phone. “They asked me to unlock my phone, they wanted to know whether we had talked or exchanged messages,” he said. “They checked whether I had any photographs of the accident that you had ended up publishing.”

We asked the police to comment on workers’ allegations that they had been trying to track down the whistleblower from Deza instead of investigating the accident on the site. In a phone interview, police investigator Jiri Hovorka rejected the suggestion, emphasising that the interrogation of Deza workers had followed standard procedure. “I cannot tell you what we did, where we did it, or what the legal reason was,” he said.

Like the police, the Environmental Inspectorate did little to follow up on the possibility that Deza might be to blame. Instead, the regulator seemed to believe that no toxins had left the site on the basis of the firm’s claim that there had been no harm to aquatic life in the pool within the waste-water management system. “Deza informed us that fish were swimming in the lagoon,” said Radka Nastoupilova, a spokeswoman for the inspectorate.

The Deza factory, owned by Andrej Babiš’ Agrofert conglomerate, is sited along the banks of the Becva. Photos: Denik Referendum, Deza whistleblowers; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

As a result of decisions taken by the police and the regulator, Deza was never treated as a suspect. Our final hope rested with the court that would hear the case against Energoaqua. If the case failed, it could re-open the debate over the accident at Deza. Judge Ludmila Gerlova began her verdict promisingly enough, by acknowledging the gaps in the evidence brought by the prosecution. Five minutes in, though, she seemed to change course, by endorsing the prosecution’s version of events. Energoaqua CEO Oldrich Havelka was facing five years in jail and a million-euro fine if convicted on environmental damage charges. But in another surprising move, Judge Gerlova downgraded the Becva poisoning from a crime to a misdemeanour.

The re-classification meant Havelka would not have to go to jail and Energoaqua would not have to pay a fine. However, the firm would also lose the usual means to appeal the decision. Downgraded to a misdemeanour, the ecocide on the Becva was no longer a matter for the courts. Any further fallout from the disaster would now be handled by the local office of the Environmental Inspectorate – the very branch of the regulator, in fact, that had failed to collect timely evidence of the ecocide. The judge refused our requests to comment at the time of the trial, and did not respond to an e-mailed request to comment for this story.

Was it All an Accident?

In the opening remarks of her ruling, Judge Gerlova acknowledged that the prosecution had assumed Energoaqua’s guilt from the outset. The police’s expert witness, Jiří Klicpera, she said, had been instructed not with ascertaining whether the company was guilty but rather, with proving how exactly it was at fault. When I interviewed him before the trial, Klicpera said Energoaqua’s guilt could be established on the basis of circumstantial evidence. The disaster had happened, he argued, because of a combination of historical factors. “You have to look many years into the past. When you piece together all the details, you will establish not one possible cause, but many. Put them together and you get an accident.”

What might the same approach – looking into the past, piecing together the details – tell us about Deza? Its owner initially seemed content with his status as a billionaire industrialist. Like other Czech oligarchs, he exerted his political influence behind the scenes. Twenty years after the fall of communism however, the Czech political scene had begun to fragment. Corruption scandals had been exposing the oligarchic hold over government. Voters were abandoning the big parties, clearing the ground for upstarts with anti-establishment messaging. Babiš entered the fray in 2011, with the launch of ANO. The oligarch’s party vowed to fix a system corrupted by oligarchs. Early campaign ads cast ANO as the lean, businesslike antidote to the rotten political establishment. “Babiš concluded that he no longer needs to manipulate the parties to make them work for him,” said Jiri Pehe, the political scientist. “He decided he could ‘do’ politics himself.”

In government, Babiš would take control of the EU subsidies that helped keep Agrofert afloat, in what the EU would later determine was a conflict of interest. Babiš rejected the EU’s finding, stating that he does not control or manage Agrofert. Babiš also appointed Richard Brabec, the former CEO of another chemical factory in the Agrofert empire, as his minister of environment. Brabec boasts that his ANO membership number, 002, reflects his rank in the party. He would install Erik Geuss, a career bureaucrat, to lead the Environmental Inspectorate. Geuss had already gutted the National Ecological Office, a body that monitors industrial pollution. At the helm of the inspectorate, he fired half the regional directors, many of whom had a track record of tackling big polluters. I later found out the inspectorate had called off investigations into two Agrofert companies that were facing heavy penalties for air pollution.

Stanislav Pernicky has fished along the Becva all his life. Photos: Stanislav Pernicky; Illustration: Sanja Pantic/BIRN

The spokeswoman for the inspectorate at the time of the Becva disaster, Radka Nastoupilova, formerly served in the same role for the ANO party. When contacted for this story, she said in an e-mail that she had “always acted in accordance with professional standards and emphasised objectivity and impartiality… I therefore unequivocally reject the allegation of a conflict of interest in this context.” Meanwhile in Valasske Mezirici, the town where Deza is based, the mayor is a member of the ANO party. At the time of the disaster, a top Deza executive and member of its board of directors, Pavel Pustejovsky, was also a member of parliament for ANO. In an e-mailed response for this story, he said he was “not aware of any conflict of interest” and emphasised that Deza had never been charged over the case.

None of the people listed above are implicated in the ecocide on the Becva – and those questioned in the parliamentary inquiry repeatedly denied any wrongdoing. None, apart from Nastoupilova and Pustejovsky, responded to requests to comment for this story. But if the circumstantial evidence had been considered with regards to Deza as it had been for Energoaqua, their actions – and their relationships to each other – might have come under closer scrutiny. Why was this evidence never considered?

Babiš’ political opponents offered their explanations. “The institutional approach to the Becva case symbolised the extent to which the public sector had been permeated by the interests of Andrej Babiš and the ANO movement,” said Marketa Pekarova Adamova, the chairwoman of TOP09, a liberal centre-right party that is currently part of the governing coalition. Another member of the coalition, Interior Minister Vit Rakusan, said the Becva case illustrated the “Agrofertisation” of Czech society. Ivan Bartos, a former minister in the coalition government, said the Environmental Inspectorate had been weakened by the “growth of a corrupt tapeworm in the state”.

Geuss and fellow ANO loyalists eventually left the inspectorate, under pressure from the new government. Brabec remains in politics. He is now serving as a regional governor for ANO. Babiš is plotting a comeback in the elections scheduled for this autumn, buoyed by the second Trump presidency and the rightward turn among EU electorates. Deza trumpets its green credentials. Its website says environmental protection is “an integral part of our corporate culture”.

Lukas Gerla, the day labourer who has fished in the Becva since boyhood, said he was “fed up” with the official response to the disaster. “I lost all my trust in the state,” he said. “And I also lost the desire to fish. I haven’t touched my rod for two years.”

This story was originally published on Balkan Insight. Zuzana Vlasatá is an investigative reporter and deputy editor-in-chief of the independent Czech daily, Denik Referendum, where she focuses on environmental issues, corporate power and state capture. This story was produced as part of the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Editing by Neil Arun.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!