Illustration: Lenka Matoušková 2025-11-27

Illustration: Lenka Matoušková 2025-11-27

In the spring of 2019, a private jet landed at the airport near Basel. What looked like a routine flight turned into an international police operation: officers seized 600 kilograms of cocaine hidden in 21 suitcases. The trail of the smuggling network led to a Balkan drug cartel, Czech pilots, and a company in which the then-director of Motol University Hospital, Miloslav Ludvík, held shares.

It was 5:26 p.m on May 16, 2019. A private jet returning from Latin America, with a stopover in Nice where the passengers disembarked, landed on the runway of the Swiss-French EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg. On board were only a flight attendant, two pilots, and the luggage.

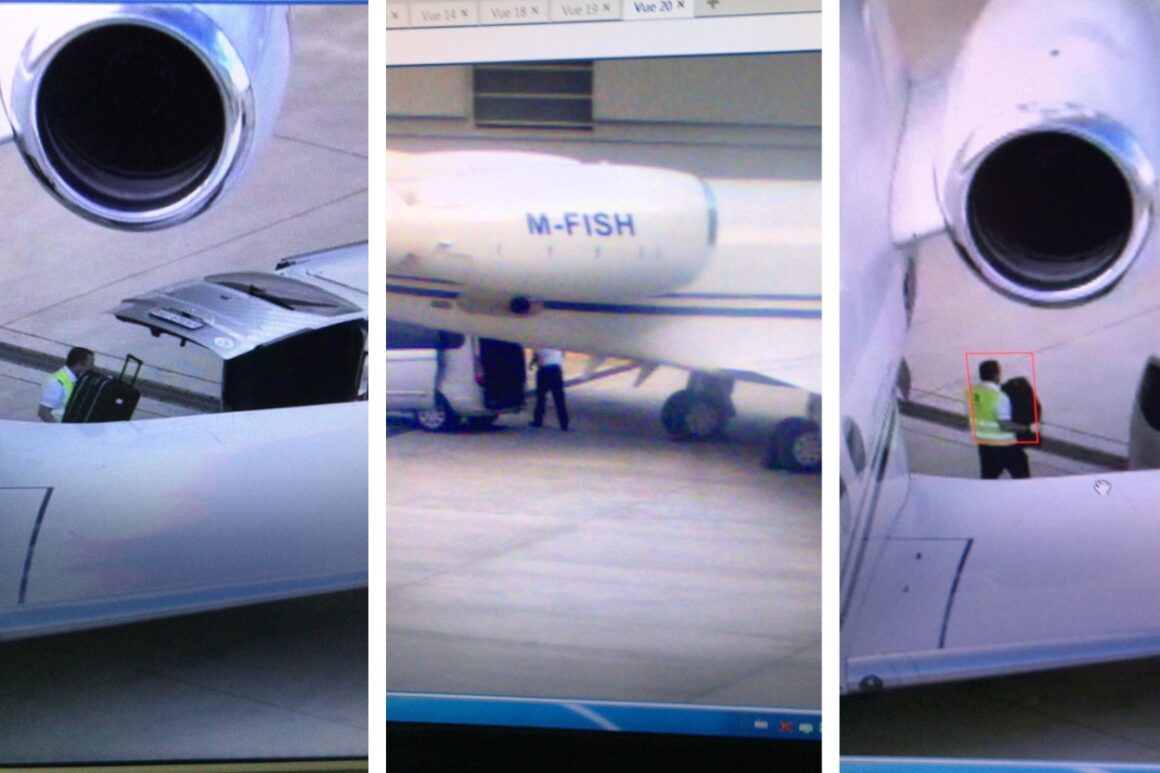

The crew stepped out onto the apron reserved for private planes. One of the pilots went to rent a car and picked up a van. The crew then began quickly loading the luggage from the plane into the van. None of the three knew that the entire operation was under police surveillance. In the 21 suitcases they were loading into the vehicle were 600 kilograms of cocaine worth at least €18 million.

But this shipment was just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath it was a large cocaine operation from Uruguay run by a Balkan cartel that used private jets to move its valuable cargo around the world.

At 5:42 p.m., the head of the Balkan cartel, Michael Dokovich, arrived at the Basel airport, according to a 2021 judgment of the Zagreb district court, which found him guilty and sentenced him to 11 years in prison. Dokovich met the pilot in a café, where he was to pay him in cash for the transport. He then got into the rented car while the pilot and the flight attendant set off to the Czech Republic in another rented vehicle. The second pilot drove away in the loaded van. The cars left the airport.

Police followed the convoy to a nearby underground car park at the Grand Casino in Basel. There they arrested one of the pilots, cartel boss Dokovich, and an associate. The flight attendant and the first pilot were arrested later in the Czech Republic.

Unloading suitcases containing cocaine at the airport. Photo: Police of the Czech Republic

Pilots Used as Police Bait?

The pilot arrested in Switzerland, Aleš Sokolík, was extradited in 2019 to Croatia, where his trial is currently under way. The second pilot, Pavel Pik, was prosecuted in the Czech Republic, but the proceedings were discontinued. The Ministry of Justice later apologized to Pik for unlawfully initiating criminal prosecution against him. The case against the flight attendant was also dropped.

The crew insist they had no idea they were transporting cocaine. Pilots of private jets do not check passengers’ luggage. According to pilot and Business Air owner Pavel Pik, they thought they were carrying gold. “Gold has historically been flown out of South America. We even declared gold in the papers – it said it was semi-processed gold destined for processing in Switzerland,” Pik said to Investigace.cz. Passengers were put on the flight because commercial cargo transport from South America requires complex paperwork. By having passengers, they could declare the flight as a tourist one. “If I deal with commercial cargo, it takes a month. With tourists, I fly in two days,” he explained.

The case against Pavel Pik in the Czech Republic was dropped. “In the court’s view, it was not possible, beyond reasonable doubt, to prove that the defendant was at least aware of the drug smuggling, let alone that he actively organized it,” acknowledged National Drug Headquarters spokesperson Lucie Šmoldasová.

According to Pik, both pilots served as bait in a police operation because officers were monitoring them. “The cops knew what they were loading into our plane in Uruguay. Europol had been chasing Dokovich for five years. And when he started booking flights through us, they did nothing. If I had found out in Uruguay what was in those bags, we’d all be dead,” he told to Investigace.cz.

The trial of the second pilot, Sokolík, began in Croatia only this August. The next hearing at the Zagreb court is scheduled for 26 November. “After that, the presentation of evidence will continue (listening to secretly recorded conversations, viewing video footage, and hearing witnesses),” the Zagreb court spokesperson told Investigace.cz via OCCRP.

Unlike the rest of the crew, the indictment claims that Sokolík met several times with cartel boss Michael Dokovich and with cocaine suppliers from South America. Investigace.cz tried to contact the pilot, but he did not respond.

“He met him because I sent him there,” Pik told Investigace.cz. According to him, they were dealing with matters concerning a plane Dokovich wanted to buy. “Sokolík was at a meeting where they spoke in Serbo-Croatian. They were talking about drugs. But Sokolík doesn’t speak Serbo-Croatian, so he just sat there and nodded,” Pik said.

Ludvík’s Shares

According to the plea agreement judgment, in 2018, Balkan cartel boss Michael Dokovich hired Czech pilots for commercial passenger flights. In reality, as the court found, he was planning cocaine transports.

The Croatian anti-corruption and organized crime unit USKOK stated that Dokovich paid around €900,000 euros for the first three flights. His next step was to acquire his own aircraft so he could organize cocaine shipments more efficiently. The Zagreb court judgment shows he had already paid a deposit of €1.1 million for the plane. In January 2019, Dokovich also founded the airline MD Global Jet in Zagreb.

According to the judgment obtained by Investigace.cz, Dokovich wanted to buy a Gulfstream G-V registered as M-FISH. That was the aircraft that landed with 600 kilograms of cocaine at the French-Swiss airport. Its operator was the private aviation company Business Air, a joint-stock company owned by one of the arrested pilots, Pavel Pik.

At the time of the police operation in which officers seized the aforementioned 600 kilograms of cocaine, the then-director of Motol University Hospital, Miloslav Ludvík, held ten shares in Business Air. Ludvík is now in custody over a corruption scandal. In 2019, Ekonomický Deník (Economic Daily) asked Ludvík about his assets, including the purchase of Business Air shares, under the Czech Freedom of Information Act. The former hospital director demanded 108,000 crowns for the release of the information.

According to the iRozhlas news site, Ludvík’s purchase of shares was recently examined by investigators. They believed he had bought Business Air shares in 2023 and failed to declare them in his asset disclosure. It later emerged that he had bought them much earlier; he documented the purchase already in 2017. He sold the shares in February last year.

According to Ludvík’s lawyer, Simona Kadlecová, her client went to the police to provide an explanation in this case. “Mr Ludvík is of the opinion that Business Air did not knowingly lend its planes to members of drug cartels,” she told Investigace.cz, adding that Ludvík met Pavel Pik while taking a course to obtain a pilot’s licence. “Their relationship was friendly, but they did not see each other often. They last met at the beginning of 2024, or possibly 2023. They may have bumped into each other at the airport after that, but only exchanged greetings,” Kadlecová said. According to her, they did not do business together.

Business Air, in which Ludvík held shares at the time of the Basel airport raid, did not own the aircraft but operated it and was responsible for it. This follows from leaked documents from several law firms obtained as part of the Pandora Papers investigation. The newsroom has a copy of the contract between Business Air and the aircraft’s owner, Osprey Wings s. r. o., which in 2015 authorized Pavel Pik and Business Air to act as operator and carry out various legal acts concerning the aircraft.

The aircraft’s owner, Osprey Wings s. r. o., had a murky ownership structure that led through the Marshall Islands and the Seychelles to a block of flats in Slovakia to a man who, according to publicly available information, could not realistically have earned enough to buy a Gulfstream. Between 2015 and 2016 he owned a now-indebted company and in 2019–2020 he ran his own small business.

The validity of the contract empowering Business Air’s owner is also supported by a publicly available reference letter from 2016 by Business Air’s majority shareholder, Pavel Pik. In it, he praises an insurance consultant and cites as evidence of his abilities the fact that he managed to insure such an “exclusive aircraft as the Gulfstream G-V”.

The company was still operating the aircraft in 2018 and 2019, when the cocaine smuggling took place. In the September 2018 brochure of a company that brokers aircraft sales, Business Air is listed as the operator. The Business Air website also advertised flights with the Gulfstream G-V, as shown by archived versions of the site from May 2019, when the police raids took place. Pik himself confirmed that Business Air operated the plane.

The company no longer operates the Gulfstream today. The aircraft has also changed ownership.

Did They Know?

According to court documents, Business Air owner and pilot Pavel Pik travelled to South America several times with the second pilot, Aleš Sokolík, at times when cocaine shipments were allegedly taking place. Pik said their first trip was because Dokovich wanted to try out the plane he planned to buy. “I don’t know if they brought any bags back – it’s not my job to check them,” Pik said.

As already mentioned, Pik — in whose fireplace police found banknotes, reportedly worth a million euros, in a box— was prosecuted in the Czech Republic, but his case was dropped. Pik said the amount was €497,000, not a million. “I withdrew it from the bank. When we fly, we carry dollars and euros, because if something happens, we have to pull out the cash and show it, and only then will they start fixing anything. Otherwise they won’t — because a bank transfer in China takes a week and a tyre costs $30,000. Something with the engine? A hundred thousand dollars,” he explained. He said he kept the money hidden in a nut box for security reasons. “I’m hardly going to carry it in a safe or in a box labelled ‘money’,” he said.

By his own account, he spent 320 days in pre-trial detention in Prague’s Pankrác prison. In the end, the Ministry of Justice apologized to him, as confirmed by a document obtained by Investigace.cz, for unlawfully initiating criminal proceedings. Pik is still suing the ministry for damages.

“The cops had a heap of coke, media glory, and tried to pin it on the pilots,” said one of the questioned participants, who did not want his name published for fear of his safety. “Do you know what someone has to go through to get into the cockpit of such a plane? These people are smart enough to know it’s a road to hell and not worth it.”

“In the pre-trial phase, the police gathered a whole range of evidence forming a logically connected chain from which it can be inferred that the accused acted at least with indirect intent; that is, they were aware that they were transporting narcotics, knew this could have criminal consequences, and were willing to accept them. Their prior, well-thought-out, targeted, cooperative, and systematic active behaviour is what demonstrates the offenders’ knowledge and intent,” National Drug Headquarters spokesperson Lucie Šmoldasová told Investigace.cz.

Investigace.cz has long reported on the activities of Balkan drug cartels in the Czech Republic. The so-called “Balkan drug route” runs through the country — one of the main routes by which drugs such as cocaine and heroin reach Europe. Balkan organized crime groups also have numerous shell companies, which they use to launder money, in the Czech Republic. “There is no criminal group from the Balkans without ties to the Czech Republic,” Serbian investigative journalist and expert on Balkan mafias Stevan Dojčinović told Investigace.cz.

The case of the Czech pilots shows how Balkan gangs also use Czechs for logistics. According to court documents, Czech pilots were supposed to transport cocaine from South America several times in 2018 and 2019.

The investigation culminated in an operation called FAMILIA, coordinated by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Europol. In 2019, police arrested 16 people and seized more than a ton of cocaine. “Law enforcement authorities from around the world joined forces against a Balkan organized crime network suspected of large-scale cocaine trafficking from South America to Europe using private jets,” the Czech police said in a press release.

There was also a question mark over why Michael Dokovich, the head of the Balkan cartel, came personally to oversee the cocaine unloading — something that is not usually done. According to National Drug Headquarters spokesperson Šmoldasová, groups involved in drug trafficking do not always have the classic hierarchical structure known from mafia films.

“A drug transport on the scale documented in operation FAMILIA is an extremely complex logistical and organizational task. It often cannot be carried out without the involvement of a higher-ranking member of the group or a broker,” Šmoldasová explained.

The Czech version of this article was published on Investigace cz.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Czech journalist, Pavla Holcová is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism. She is an editor at OCCRP and a member of ICIJ. She was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2023). Pavla is the winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award and, with her colleagues Arpád Soltész and Eva Kubániová, the World Justice Project’s Anthony Lewis Prize Award. She is based in Prague.