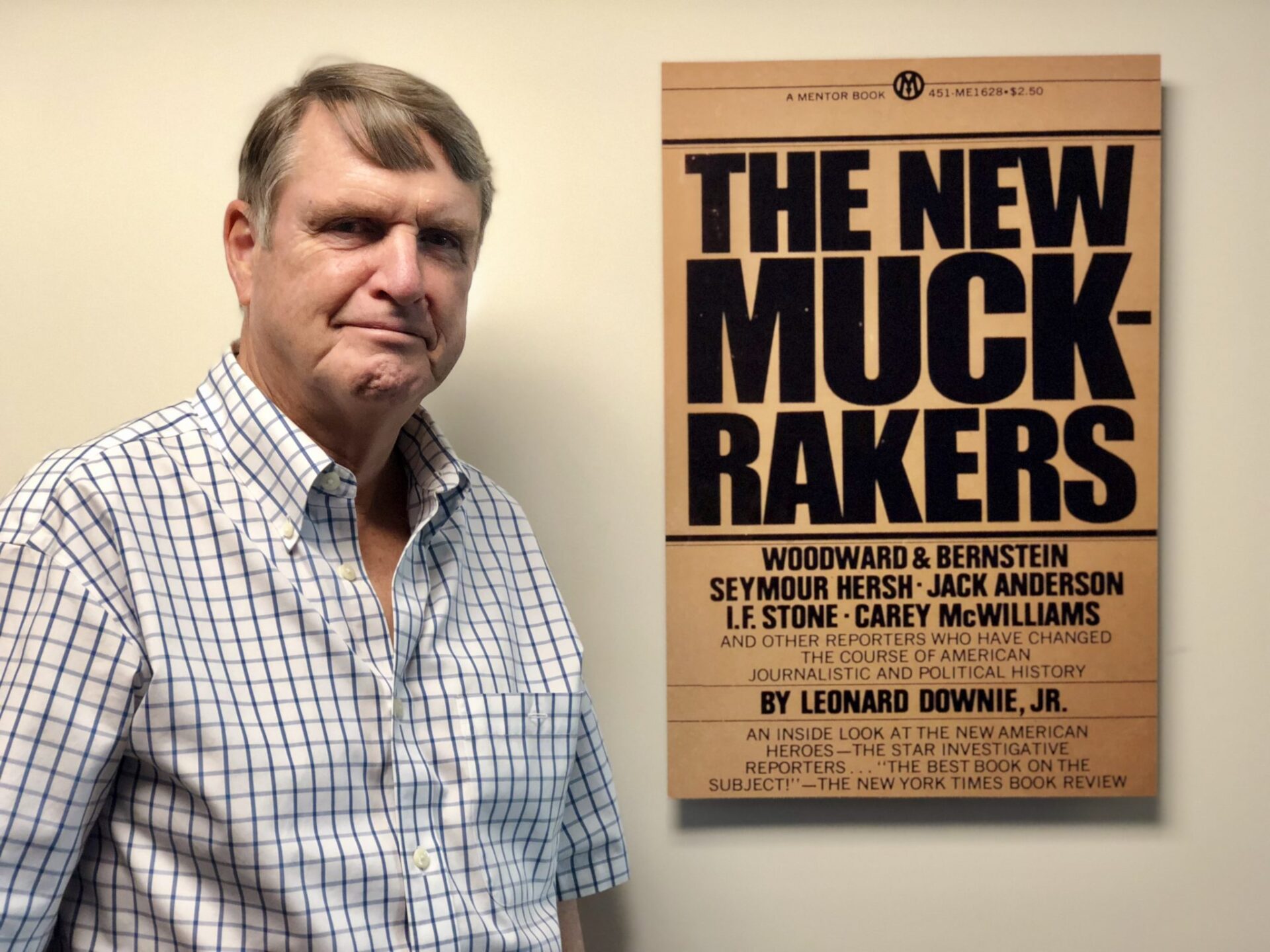

It turns out that the Trump and Nixon White House are not that much different. Neither is their hatred towards journalists, says Len Downie Jr., former executive editor of The Washington Post. We sat down with him to talk about the evolution of investigative journalism.

Leonard “Len” Downie Jr. joined The Washington Post in 1964. As an editor of the Metropolitan staff, he supervised the Post’s Watergate coverage in the ‘70s, worked as a London correspondent in the early ’80s before becoming the Post’s managing editor (1984-1991) and executive editor (1991-2008). He is the Weil Family Professor of Journalism at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, teaching accountability journalism. Downie has authored several books, currently he’s working on his memoir.

Was investigative journalism really invented in the United States?

There was a period at the beginning of the 20th century, the so-called Muckrakers period, when particular groups of journalists essentially began investigative reporting in the United States. Few of them were writing for newspapers, more for magazines like one named McClure, or they were publishing books. Back then, all newspaper circulation was local. Magazines were newly popular because printing operations were national, and of course books were circulated nationally too.

These journalists investigated the big monopolies, the meatpacking industry, corruption in government, both local and national, and so on. President Theodore Roosevelt took notice of them and actually was able to use the furor created by some of their writings to push through laws like the Antitrust Act or the law that created the Food and Drug Administration. At some point, when these journalists started investigating politicians too close to Roosevelt, the president made a famous speech in which he praised and criticized them at the same time. The president compared them to the man with the muckrake, and they happily called themselves the ‘Muckrakers’ as a result.

Then Muckraking journalism sort of died down during the two World Wars, the Great Depression and the McCarthy-era. Magazines disappeared, the newspapers turned into depression. There was little investigative reporting in this period, virtually none about national subjects and the national government. There were exceptions like Life Magazine, a nationally syndicated columnist named Drew Pearson, or Edward R. Murrow in radio and television. So it was beginning to crop up here and there again, locally too.

The government was also encouraging journalists investigating the mafia, so investigations of organized crime began in various cities, including where I was growing up in Cleveland. I saw these articles in the local paper, so this must be the late fifties. But that was about it. Those of use who were later doing investigative reporting locally in the sixties were covering local subjects like the courts, local corruption and that sort of thing. It wasn’t really until the Pentagon Papers decision and then Watergate that the idea that the national government should be held accountable by journalists was brought in. In the early months of Watergate, the Post was alone on the story because there was no interest in it. Not only not in the country, but not in the news media.

It wasn’t normal to think that the president and the people around him should be investigated. This wasn’t something that journalist did back then.

So it was like in the movie All The President’s Men, meaning that you came to understand step by step how severe the issue was?

Yes, it was day by day. As soon as the White House connection was established and as we gradually found out about the other things that were going on, it became clear this was really important. Whether it reached the level of the president of the United States or not, we didn’t know for a long time.

Was there really a fight – like portrayed in the movie – to keep the story within the metro desk and not let the national desk getting their hands on it?

Yes, more than once! Watergate was a local story because it started as a local break-in in Washington DC. Back then I was the deputy metro editor, the number two editor on the metro staff. At first, the national staff’s people didn’t believe in the story. They in fact told executive editor Ben Bradlee to stop it. It was outside of their idea of politics and government, they couldn’t fathom that. Then once they got that something is going on, they wanted to get on it.

By the end, of course, it became properly a national story when the president was about to resign. But that was no longer the investigative part of Watergate.

Did you also have to defend Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein from the national team?

Harry Rosenfeld, my boss, was pretty good at it, but yes, I also had conversations.

Watergate was the biggest story investigative reporting has ever produced. I guess it could never happen again since the whole media environment is totally different.

Yes, it’s so much different. Woodward and Bernstein were the first real journalists that a movie was made about. All other previous movies about journalism were fiction. Now you see the investigations going on about Trump where every newspaper is involved.

How different is the Trump White House from Nixon’s?

It’s interesting because it turns out that, in whole, it’s not that much different. The things Trump tweets, Nixon also said inside the Oval Office.

We just didn’t know it back then until we heard them on the Nixon White House tapes. Their attitudes are the same, saying exactly the same kinds of things. We eventually found out that Nixon was wiretapping phones, so he was even more aggressive in harassing the press. But Trump is more aggressive verbally.

Do you think that Trump’s attacks on the media really incite hatred towards journalists?

Journalists have never been popular. I assume that’s also the case in Hungary, not just the United States – because we hold up a mirror to people and they don’t always like what they see.

I never thought journalists need to be popular. But there is a more virulent hatred against the press going on right now by people who are supporters of Trump, and that does worry me some. They wrongly blame the press for exposing what they should instead be concerned about.

Was it similar during Watergate? Did Nixon’s supporters have the same feeling towards the press?

Nixon had a list of his enemies, and he thought the press is also an enemy. I’m sure there were a lot of people supportive of that sentiment since Nixon was a popular president, he was re-elected by a huge margin. I think even at the time when he resigned, probably half of the country still supported him. What’s different now is that the digital media magnifies everything, including criticism of media and hatred of media.

Was the Nixon White House as leaky as Trump’s?

No, I have never seen a White House leaking as much as this. The Clinton administration was a little like the Trump White House, somewhat chaotic, with a lot of arguing going on. There was a tendency to find out more about things than during other White Houses, but still the Clinton White House was nothing like this. This is bizarre.

Sourcing was a very important part of the Watergate investigation. Does anonymous sourcing – as we currently know it – date back to that era?

I like to call them confidential sources, not anonymous, because they are real people, and you know them, and the editors also know who they are. Confidential sources certainly date back to Watergate. And Watergate was almost entirely reported with confidential sources, because sources were all inside the government and could lose their jobs.

So before Watergate, it wasn’t really a practice to quote information from people without naming them?

In terms of investigative reporting, I’m not remembering that very much at the time. I did a series of articles about the local court system in Washington DC in the mid-sixties and I may have had some confidential sources for that, unnamed sources. But I’m not sure if I quoted confidential sources as opposed to just using information from people that I was able to corroborate otherwise. But Watergate was certainly the big move forward on that.

Do you feel that in recent years, the rules of sourcing and attribution in journalism have become much looser?

There is just so many different media. I know what the rules are that we followed at the Post and I think everybody should follow, but that doesn’t mean that everybody else is going to do that. American media, in my opinion, needs to become more transparent about what they are doing and where the information comes from. When you are using confidential sources, say why you are using them, how many youare using, and what their bona fides are.

I remember a story Carol Leonnig worked on with others at the Post, which said right away that the article is based on twelve interviews with twelve confidential sources in the White House, people that talk to people in the White House, and people on the Hill. So at least there you got an idea that these are real people, and that they know what they are talking about, even though they can’t be named.

After your years as the editor at the Post’s metro desk, you became the newspaper’s London correspondent in 1979. How different was investigative reporting in the UK back then?

That is the other thing I was going to say. Because outside of investigative reporting, confidential sourcing was typical in lots of reporting, especially about the government, where government officials never wanted to be named. Like, for example, in Britain the case was that they had a so-called lobby system, where each government agency and the prime minister’s office had its own lobby, meaning background briefings for journalists all the time. And stories based on those talked about “is learned that”, “is known that”, “is believed that”. It wasn’t the American convention of saying “three confidential sources told this yesterday”. But I think that’s very typical, or had been in journalism elsewhere in the past.

The Sunday Times was one of the leaders of investigative reporting under Harry Evans. They were doing investigations, but not so much of the government. And in fact, Harry told me personally when I was in London that they never could have done Watergate. Because there is the denoted system, where if the government wants to stop you from doing something, it claims it’s potentially harmful to national security, and they simply issue a secret notice to you, saying “stop”. And you have to stop.

How did the rules and skills of investigative reporting evolve throughout this period of time?

I wasn’t a leader, but I was one of the half dozen people who started the Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) group after Watergate in 1975 for exactly that reason (the evolution of investigative journalism – VSquare).

Because otherwise investigative journalism was simply self-taught, or somebody else in the newsroom showed how to do it. I was self-taught for instance, nobody showed me what to do.

IRE was started because we decided we need training, we need to share techniques, we need rewarding people for good work, and so on. Once IRE was growing and investigative reporting was all over the place in the United States, we began to see it happening in other countries in the world.

Later even international cooperation dispatched, in part at the time after 9/11, when it became obvious that investigations are necessary on some of the anti-terrorism measures carried out by the CIA. The CIA was snatching people up and flying around the world, putting them in secret prisons. Journalists in other parts of the world were following these planes by the tail marks, and started cooperating with American journalists. That is the first international cooperation among journalists on a higher scale I’m aware of.

Going back to the Pentagon Papers: you were a consultant for Steven Spielberg’s recent movie, The Post. How did you like the way it portrayed the people you knew in person- Meryl Streep as publisher Kay Graham, Tom Hanks as executive editor Ben Bradlee and so on?

I think it was brilliantly done, not only by the director but also the actors. All of them have studied their people really well and asked me good questions about them. Also, the movie portrayed journalism really well too. There were a few cinematic things that I wouldn’t done if I was making a movie – but that’s why I’m not Steven Spielberg. Like having Ben send someone off to the New York Times to spy on them. That didn’t happen. But apart from that, it was very accurate.

To make the movie more authentic, you dissuaded the producers from decorating the Washington Post newsroom with certain cartoons. Why did this matter?

Herblock (Herbert Block) was a very famous American editorial cartoonist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes and worked for the Post for decades. Herblock was very closely identified with the newspaper. So I guess that’s why the the producers had the idea of putting up his cartoons in the newsroom to show: this is the Washington Post. But when Ben Bradlee came along as the new executive editor, he created a very strict separation between news gathering and the editorial page. Ben reported separately to the publisher from the editor of the editorial page.

Because of this separation – it is like the separation of church and state, they are the church, we are the state – we never would have had Herblock cartoons hanging up in the newsroom.

It was very important to Ben that the paper not be opinionated, not be ideological in its news coverage. That’s for the editorial page to deal with. So for example long after the Washington Post war correspondents were writing stories which raised real questions about the war in Vietnam, the editorial page was strongly supporting the war still.

Did this lead to debates?

No, because the editorial page was none of our business, and our coverage was none of their business. We were doing investigative stories about Marion Barry, the mayor of DC, while the newspaper’s editorial page was endorsing him. That was the only time when the editorial page editor did come out and say: “Look, we’re endorsing this guy, why are you doing this?”. I told him: “Go back to your office, leave me alone!”.

What do you think about today’s journalism, where mixing news pieces with opinion and analysis is on the rise, and sometimes there is no separation at all?

I kind of got used to the fact that there is this thing called ‘voice’ in news gathering as opposed to editorial writing, in some of the blogs, the newsletters, and even in some of the stories, in the news sections of websites and newspapers. There is more voice in it than before, more analysis. Now some of that is good, when we are talking about expert reporters, experts of the topic that they are covering. I benefit from their expertise as a reader.

But what I don’t want to do is to cross into personal opinion, and to be pro-Trump or anti-Trump in news stories or news presentations for example. And on websites I respect there is a separation of the opinion and the news still. But then there’s a lots of other media like Fox News on the conservative side and MSNBC on the liberal side, where it’s stunning to see that they are supposed to be news programs but they are completely opinionated.

But there is also a role for the more edgier sites. There is a website that has won the Pulitzer Prize for environmental reporting that is strongly pro-environmental protection. Not a point of view we would take as editors at the Post, but nevertheless they do good journalism in pursuit of that. It’s a different time now. It took me a while to get used to some of these things, because it’s not the way we grew up in journalism.

I don’t think that the separation of church and state is outdated, but some news organizations still adhere to it and others don’t.

In the US, you rarely see senior editors appearing on TV to comment on daily politics. The separation exists there too. Why is it important to refrain from publicly expressing your political opinion as an editor?

Because as final gatekeepers for what is in our publication we should keep a completely open mind. I was famous for not voting during my twenty-five years as managing editor and executive editor at the Post, whereas my counterpart at the Financial Times, whom I really respect, is on television expressing views all the time – but that’s a British tradition.

When I was over there in Britain and wanted to figure out what’s going on through the British press, I had to read six or seven newspapers every day, because each one would had a different slice from a different point of view. And you had to put them all together to know what the hell is going on. But that’s a different tradition. And there was a time when the press was partisan in the US, too. It continued from the founding of the country all the way through the Civil War, well into the late nineteenth century. It was only at the beginning of the twentieth century that this separation between opinion and news began to grow up.

Do you think that in other parts of the world, where free press is a more recent development, like in the former Eastern Bloc countries, it just takes time to create similarly strong institutions of journalism, strict policies and practices in editing and investigating?

Yes. On one hand, it does takes time. On the other hand, it’s more difficult in the digital age where everything is going on at once.

You are a big advocate for non-profit journalism. Do you think it can really help the public by covering all those areas – from local journalism to investigative journalism – that are sometimes left uncovered by profit driven mainstream outlets?

Definitely, they are a big help. Whether they are the solution or not, we just don’t know yet. But I think they will stay around too. Not all will, because most of them are financially frail. Some are going to cease, but new ones will be started. It is an essential part of the American media ecosystem to have these non-profits. Some of them are doing local coverage, some of them are doing investigative reporting, often collaborating with the commercial media.

Is this also a very recent development?

Yes, it started in the last ten years. When I was the editor of the Post we didn’t collaborate with non-profits, mostly because they have not existed. Now they exists, and now big papers collaborate with them. For instance, I’m the chair of the advisory committee of the Kaiser Health News, and there would be much less health coverage in this country if it weren’t for Kaiser.

What do you tell to your students who are looking for a career in today’s journalism?

I don’t worry if newspapers are going to last forever or not because there are substitutes to that. What I tell to the students is that you do have to be good to get a job.

It’s not easy, it’s long hours and antisocial, and you have to decide to dedicate your life to that.

But if you do, and if you become multimedia skilled, there are plenty of jobs for you. Because even if the total number of employment in journalism has decreased, the number of jobs that require multimedia and digital approaches are growing.

This is a wild guess, but less than half the people I hired at the Post or were hired during my years went to journalism school. I think journalism school has become more important now because of the digital age, all the skills you have to have now. And you’re not going to pick them up as quickly as you can in a journalism school.

A lot of the Post’s Pulitzer Prize winning investigations were carried out by female journalists, whom you hired. Was there a conscious attempt to have more female investigative journalists at the Post?

When I was a young investigative reporter, I don’t think I knew any, or maybe one or two female investigative journalists. Obviously as more women got into journalism, it changed. Two things were going on at once. I think we were just hiring more women who turned out to be good investigative journalists, and we made sure they got their opportunities. But also at the same time the paper had a policy to try to increase its gender diversity steadily through the years, which we succeeded doing.

We wanted talented people regardless of gender and color, because if you’re not paying attention to talents who are not white male, your staff won’t be as strong as it would be otherwise.

How do you consume your news?

I read everything. I read on my computer, on my phone, and I still read printed newspapers, the Times and the Post principally.

Which are your favorite political dramas and shows on Netflix and elsewhere?

House of Cards was one of my favorites for a while but then I thought it ran too long, even before the actor got into his personal trouble. Homeland – although I think it has been a little of a stretch for them too lately. And I love The Americans, and I think they are ending it in the right time. But if there is another season I don’t think I could stand it anymore.

When the last season of House of Cards came out, a lot of people said that real life politics has become more absurd than fiction, making the series less interesting.

Absolutely. We just watched Homeland and although they are doing their absolute best, they are having a hard time having to try out really weird plots now. They have got the same things going on in the series as in real life, but they have to kill more people and so on. They just had a raid in Moscow, and that sort of thing.

Which was actually shot in Budapest.

I was wondering where it was, thank you for telling me! Because it had a lot of street scenes and I was wondering where it was. Good to know!

Photos: Szabolcs Panyi