Julia Dauksza, Konrad Szczygieł (Fundacja Reporterów)

Daniel Antoni (ICJK)

Hana Čápová, Eva Kubániová (investigace.cz)

Illustration: Lenka Matoušková

Infographics: Attila Bátorfy 2020-03-29

Julia Dauksza, Konrad Szczygieł (Fundacja Reporterów)

Daniel Antoni (ICJK)

Hana Čápová, Eva Kubániová (investigace.cz)

Illustration: Lenka Matoušková

Infographics: Attila Bátorfy 2020-03-29

A surgical mask with two thin elastic straps will likely become a symbol of the current crisis, the extent of which has caught many governments by surprise. Shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic, millions of masks were exported from Poland and Slovakia. Medical personnel in Hungary, Slovakia and Poland are struggling with shortages of protective equipment. There is no basic information on protective clothing or the number of doctors. So far, the spread of the epidemic has been slowed down by self-isolation and a nationwide lockdowns, but it is clear that the coronavirus has exposed the weakness of the healthcare and crisis management systems.

Slovakia seems to have had the largest share of bad luck. When coronavirus was at the country’s gates, a government reshuffle was underway. Initially, public events were banned as early as March 10 but the ban was soon expanded to include public gatherings; shops, schools and universities were closed and a state of emergency declared in public healthcare facilities. Still, there was no one to make other strategic decisions. When neighbouring countries introduced emergency plans for the economy and placed bids in tenders for protective face masks, Slovakia was waiting for a new prime minister.

The first time the new Slovak government met was on March 23, and although the authorities in Bratislava are now taking decisive actions, there was a visible break in the continuity of the administration; and some information about the pandemic is still kept under wraps.

It took five days to release even basic information about number of patients hospitalised with suspected infection. But how many are outside medical facilities? How many are in self-quarantine? Is there a sufficient number of face masks to allow emergency services to continue their duties to ensure that the citizens are safe? That is something no one knows.

Lack of knowledge, fear and uncertainty is something all Visegrad Group countries share.

A new Slovak government, credit: Veronika Remišová instragram

The face mask as a state secret

In early March, the coronavirus outbreak forced the governments of Hungary, Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic to introduce a state of [epidemic] emergency. They take similar actions with only minor differences – within days they close their borders to foreigners. Only their citizens or permanent residents are allowed to enter. All airports that handle international flights are also closed.

At first glance, the administration works fine – it adopts regulations and restrictions and issues bans. The police have powers to check on people who should remain in self-isolation at home. Everyone must remember the need for social distancing. Residents comply with government requirements – the number of instances when people break self-isolation rules are rare.

Despite this, the number of those infected is increasing. As we approach the peak of the epidemic, more people have to be treated at infectious diseases wards, and the question “Are there enough masks?” reverberates more often in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia.

Slovak hospitals are not ready for the crisis. National stocks of ventilators and face masks are only symbolic. Medical staff quickly turn to social networking sites to post the following message: “we need more face masks.”

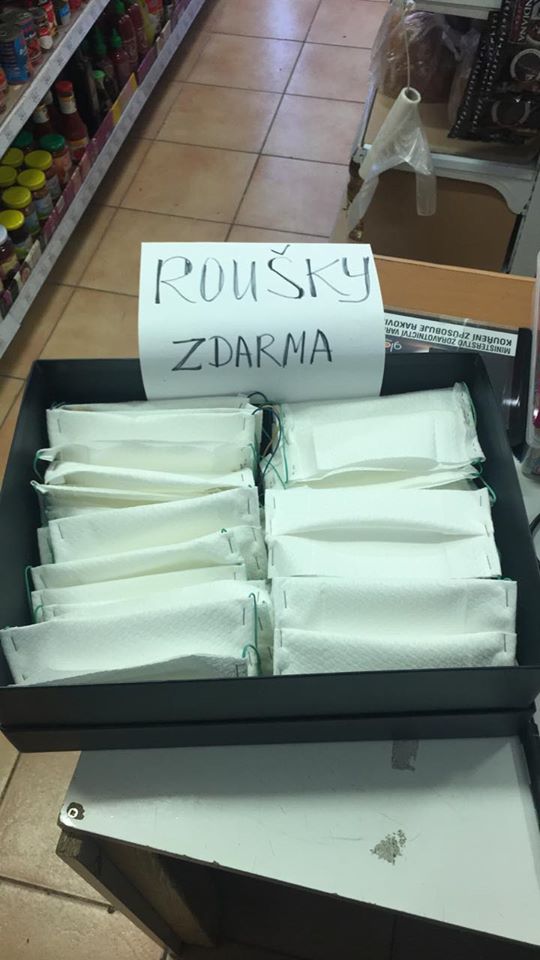

“Free masks” offered in a Czech shop, credit: Facebook fanpage Prague 7

Poland also suffered from a shortage of masks. It is clear already on the first day of the epidemic. As first patients appear, even the hospitals that declared to be ready for COVID-19 begin to call for additional masks, goggles and gloves. Now they estimate the use of personal protection equipment at over 100.000 kits per month – for every hundred of infected patients.

In Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia people organise themselves online and begin sewing masks to help shield doctors and patients. They use whatever they can lay their hands on at home.

We are unable to discover what the shortages are in the four countries. The exact numbers are not available to the public. Why? Because such information is a state secret. In Poland, reserve stocks of equipment such as face masks are overseen by the Material Reserves Agency (which manages strategic reserves). The Ministry of Health informed us that it had delivered 260,000 HEPA masks and 770,000 surgical masks from reserve stocks to hospitals and ambulance teams. It did not answer the question how these amounts relate to the actual demand reported by hospitals. “Millions” of masks and “hundreds of thousands” of protective overalls are said to be contracted and on the way to Poland.

The government knows but don’t be too inquisitive

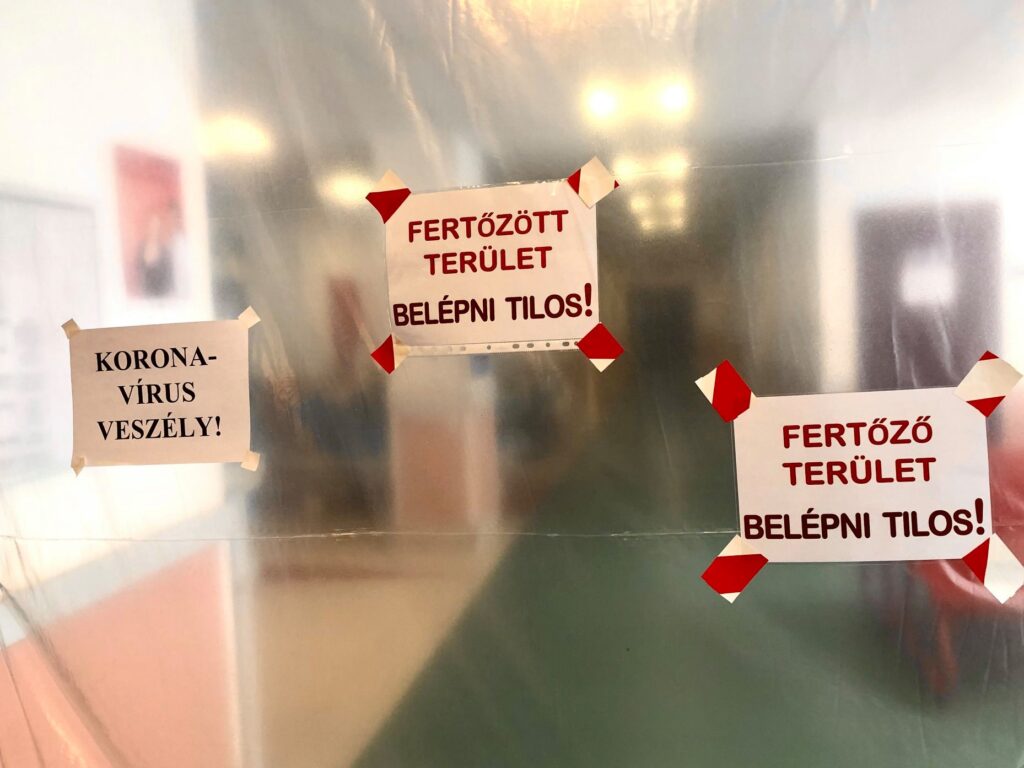

On March 19, journalists from Atlatszo.hu interviewed a doctor who works in downtown Budapest. Although by then the country had already declared a state of epidemic emergency, the doctor was confused. He has no idea where he will be able to get hand disinfectant products or face masks. The government fails to provide hard data and often resorts to keeping information from the public. General practitioners did not get anywhere near enough suitable masks, there is a shortage of gloves and disinfectants. HEPA masks? All doctors from Budapest and the Pest county at that point had to travel to a main warehouse to pick up the protective equipment themselves. They can get up to three masks per surgery.

The main problem in Hungary is the lack of reliable information on the epidemic. The propaganda machine controlled by the government only supports the official government line. Daily press conferences dedicated to the crisis provide answers only to a carefully selected set of questions, with any uncomfortable ones removed from the pool.

Is there a shortage of face masks in Hungary? In official statements, Prime Minister Viktor Orban assures that is not the case and pledges that Hungary would soon be churning out 80,000 masks per day. At the same time, the Hungarian Association of Ambulance Workers is collecting masks and funds on Facebook – the latter will be used to help distribute protective equipment around the country. A few days prior, Hungary’s Medical Chamber put up an anonymous online questionnaire for doctors in an attempt to assess current deficiencies.

However, the government focuses on other issues. After it introduces the state of epidemic emergency, the authorities and media favoured by the country’s government draw attention to several Iranian students. That group – they allege – is where the country’s patient zero originated. All of this is intended to show the coronavirus epidemic has been caused by a migration problem.

“Danger of coronavirus! Infected area! No entry!” the titles in one of Budapest hospitals, credit: SZent Imre Hospital facebook page

Prague reacts quickly

The Czech Republic is fast and very efficient in dealing with the epidemic. On February 22, Italy announces the first death caused by the new disease. Just two days later, Czech Minister of Health Adam Vojtěch announces the country would set up the Central Epidemiological Commission for Coronavirus. The Czech Republic is not planning to introduce any restrictions yet but is monitoring the situation in Italy, where new patients die and the number of infections is growing exponentially.

On February 25, PM Andrej Babis encourages people not to travel to Italy. At the end of February, the first tests for the presence of coronavirus are carried out, almost 100 people are tested.

On March 1, three people are found to be infected with the virus. Three weeks later, the first coronavirus victim in the Czech Republic dies.

Prague is among the few capitals that quickly adopt tightened measures. Less than a week after the first cases are confirmed, Prime Minister Babiš decided that everyone returning from Italy will have to go into self-isolation for two weeks – a total of 16,500 people, according to official estimates. If you fail to comply with the self-isolation rules, you may face the maximum penalty of a mind-boggling CZK 3 million (approx. EUR 110,000).

The government requires citizens to wear masks in public – but you just can’t purchase them. However, you do not have to wait long for the problem to be solved: “Czechs sew face masks” is one of several dozen groups on Facebook, which form spontaneously at the request of healthcare professionals. Everyone joins in the effort – people who have a sewing machine at home and professional tailors. Several clothing factories are now stitching together face masks for the country’s hospitals.

“Those are our last disposable face masks. Please help!” health workers in Prague wrote on Facebook. The next day people sent them home-made face masks. Credit: Facebook fan-page Prague 7

You can even make a fashion statement. Some members of the government appear at press conferences in colourful, hand-made masks.

In practice, that very method worked in the fight against the coronavirus in Taiwan: “My mask protects you, and your mask protects me.” The head of the country’s Central Crisis Staff Roman Prymula believes that the government will recommend wearing masks until the number of cases goes down. But isn’t it a problem that those are DIY masks? Well, if people were to use disposable face masks, the Czech Republic would need 300 million masks a month.

Mask prices go up

Today, the so-called HEPA masks are a critical commodity almost everywhere. In the event of direct or prolonged contact with an infected person, the medical crew should use type FFP2 / FFP3 (these symbols indicate levels of protection), which are closely fitted as well as hazmat or waterproof suits, disposable gloves, goggles and, if available, a face shield. Face masks typically need to be replaced after four hours.

But HEPA masks are very expensive today – and they are simply not available in any of the four countries. After the outbreak, as the sales of face masks on the Polish auction website Allegro soared, the government stepped in and banned the sale of masks. Many distributors and wholesalers say that the next delivery will reach Central Europe in April. The price of face masks has increased several times since January.

China: you may take your masks

Procurement proceedings are the easiest method of buying masks. The so-called Joint Procurement Mechanism (JPM) has been in place in the European Union since 2014. The EU procurement scheme allows up to 28 countries to take part in large, simplified and quick tenders for, among other things, medical equipment.

We learned that even though all countries of the Visegrad Group joined the JPM, none took part in two European tenders organised in March (among others for protective equipment in the fight against the coronavirus, including masks). Each of the countries has opened its own tenders instead.

In most cases, masks are supplied by companies with links to China – because this country is the world’s largest producer of face masks. But it turns out that Beijing also purchased masks overseas.

Chinese respirator FFP2 delivered to the Czech Republic. Credit: Twitter Jan Hamáček (Minister of the Interior)

Just before the coronavirus outbreak in Europe, the Polish company LPP, a giant on the clothing market, bought 500,000 face masks that were available on the market and sent them to China. Officially – as humanitarian aid for the regions that were fighting the virus. The company failed to disclose that most of the masks were shipped to China to back up the sewing factories.

Slovakia also exported masks and other protective equipment amounting to EUR 3 million to China labelling it as humanitarian aid. One of the business owners later admitted that the gesture that removed protective equipment from the Slovak market aimed at maintaining good relations with Chinese business partners and wasn’t a heartfelt decision.

There are also bigger scandals associated with the procurement schemes for face masks. In March, when the Slovak government opened quick tenders for masks, protective clothing and tests, it spent EUR 44 million for that purpose. Among the winning bids, journalists find two companies (A-testing and LACORP), which have won contracts for several dozen million euros. But they are resellers, they will buy the equipment abroad. Both companies did not even exist before the outbreak.

It soon turns out that one of the winning bids exceeded the market price by EUR 13 million. As a result, the government sacked the head of the Material Reserve Agency Kajetán Kičura. Journalists discovered that his 20-year-old son now owns two apartments in downtown Bratislava and bought them at the same time the tender was carried out, without even taking out a loan. The police are investigating the matter.

The coronavirus pandemic in Central Europe became – as ambiguous as it is – China’s triumphant return, as the country has gradually been withdrawing from the region for several years. On March 23, a shipment of 30,050 hazmat suits and 82,000 medical masks arrived in Hungary. A few days ago, China promised to send 20,000 HEPA masks to Poland, which would be enough for only several days. In the meantime, the Chinese also delivered masks to the Czech Republic, but from the moment the shipment arrived, their quality was criticised on social networking sites – the fabric was thinner than indicated in the tender specification. For now, the Czech Minister of Health is still wearing a homemade mask. He officially denies that there is a shortage of disposable masks in the country.

After several difficult weeks of the pandemic, when chaos and disinformation reigned, the Visegrad Group countries seem to have regained control. At least, this is what they officially claim. Hungary has 22 million pairs of gloves and 1.2 million surgical masks while another 1 million surgical masks will soon arrive in the country. In Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic government officials are talking about millions of pieces of protective equipment that has already arrived there. And people are still staying at home and making face masks for local hospitals.

Preventive equipment, which is crucial for saving lives and controlling the spread of the epidemic, is slowly becoming a secondary topic. Today, the public is focusing on charts and numbers: how many people are infected every day? How many have already died?

At a time when numbers are the most important and when people die as a result of the epidemic, no one pays attention to the fact that the new laws and regulations that have been put in place strengthen the hand of those in power. Who at the time of the worldwide epidemic worries about the fact that an app distributed by the Polish government labelled “Home Quarantine” collects sensitive data about users, passing it on to the police and a small company nobody has heard of?

Who is concerned with the fact that Hungary is seeking to detain journalists for spreading “false” information about COVID-19? And when Tamás Deutsch, head of the Hungarian National Delegation to the European Parliament, was asked about it, he responded to the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe: “Mind your own business!”.

Today the numbers are what counts.

This text was financially supported by GACC (The Global Anti-Corruption Consortium) aimed at the Visegrad countries. Member centers Átlátszo and Direkt36 from Hungary, Fundacja Reporterów from Poland, Ján Kuciak Investigative Center from Slovakia and investigace.cz from the Czech Republic are working on the project.