Cover image: Aleksandra Ołdak

Visual storytelling: Anastasiia Morozova, Tadeusz Michrowski 2024-10-24

Cover image: Aleksandra Ołdak

Visual storytelling: Anastasiia Morozova, Tadeusz Michrowski 2024-10-24

The Polish fuel giant, Orlen, claims to be fighting for the environment and presents itself as being at the forefront of an “energy transformation.”’

In reality, the company is fighting to preserve profits, and is hoping to use Poland’s slow green transformation to hold onto the last oil refinery in Europe.

Over the years, Orlen has boosted its brand image with the presence on the controversial “World’s Most Ethical Companies” list.

But a number of Orlen’s green declarations are based on unproven technologies and trading partners whose supply chains the company pointedly doesn’t take into account. Some of those partners come from the U.S.

Orlen is a publicly traded company, owned mostly by the Polish state and large pension funds.

In September 2020, Orlen, Central Eastern Europe’s biggest energy company, issued an announcement: “PKN Orlen, as the first fuel company from Central Europe, has declared the goal of achieving carbon neutrality in 2050.” This lead sentence was republished by the various media outlets, which also reported on the temporary change in Orlen’s logo, an eagle, which was now green instead of red.

The message was simple: the largest oil company in this part of Europe is responding to the challenges of climate change. It is to become a “leader in energy transformation.” The company announced new investments, contracts and the development of green and low-carbon energies. For the next few years, stock market reports, industry articles, press releases, and local media outlets all dutifully reported the line.

The promise worked for investors as well. When Orlen issued “green bonds” for €500 million, investors were willing ready to invest six times as much.

But not everyone shared the enthusiasm.

In June 2023, Orlen shareholders assembled for their general meeting. The event attracted some unexpected guests. Environmental activists gathered in front of the wrought-iron fence of the Dom Technika, a civic center, in Plock. The banner they posed with read: “Enough of turning transformation into a circus.” Among the activists present was a person in a clown costume and a mask that resembled the face of the CEO of Orlen. He swayed to the rhythm of music played from a speaker.

“We called it the Orlen circus because we decided that if the people from Orlen don’t want to call a spade a spade, don’t want to say frankly that, all in all, we don’t care about you Poles, about your planet, then at least we will say how it is,” Dominika Lasota, a climate activist from Inicjatywa Wschód NGO, said at the time in an interview with TOK FM radio.

Stanislaw Baranski, director of the Office of Sustainable Development and Energy Transformation at Orlen responded to these accusations (as quoted by wysokienapiecie.pl) a few months later. “We are not afraid of accusations of greenwashing because we are aware of the risks and liabilities. The energy industry has to respond to very real expectations. Greenwashing is therefore not worth it.”

Greenwashing is the term used to describe marketing that misrepresents how environmentally friendly a company, product or service is. No one willingly admits to greenwashing, and companies deliberately blur the line between this practice and what they themselves call communications or PR. “We have not yet investigated the Orlen company in this respect,” admits Kamila Guzowska of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection, which deals with such matters.

VSquare has done just this investigation. We have compared Orlen’s communications and PR missives with the facts. For years, the company has consistently pursued policies with the priority of preserving profits. It intelligently works with regulations and dilutes responsibility with PR hype.

We have nice targets, wanna buy oil?

The key to understanding what Orlen’s greenwashing is and where it comes from are the targets the company has adopted: the declared ones and the actual ones.

The strategy announced in 2020, and supplemented thereafter, promised to reduce Orlen’s environmental impact primarily in terms of carbon dioxide emissions (the gas that contributes most to climate change).

The carbon emissions are measured in three ways, referred to by energy analysts as "scopes".

First, they measure emissions from fuels burned by the company itself, such as by its trucks or in power plants or during the production process.

The second scope is indirect emissions, i.e. those that arise elsewhere but result from the company's activities, such as the electricity it buys.

The third scope is basically all emissions that can be linked to the company's activities through all of its value chain— from the services and goods it buys to those produced by it.

The total emissions are the sum of all three scopes.

In the case of companies that produce raw materials and fuels, such as Orlen, the third measurement of emissions is often a multiple of the first.

This includes emissions from sold (and burnt) fuels.

According to reports on Orlen's website, in 2022, the group emitted the equivalent of 21 million tons of carbon dioxide in the first scope...

...and 107.5 million tons in the third.

Back then, Orlen's carbon dioxide emissions just under the first way of measuring accounted for one-fifth of the category's emissions for the entire Polish industry.

What exactly is Orlen promising?

Orlen is pledging that, by 2030, emissions from the refining, petrochemical and upstream segments will fall by 25 percent compared to 2019. So: collectively, these parts of Orlen will emit a quarter less.

By 2030, emissions as measured by the three methods combined will be reduced by 15 percent.

This means that, expressed in megajoules, the energy created by Orlen's operations and also from the products it sells (e.g. from the fuel it burns, which the company sells) will have, combined, a 15 percent lower carbon footprint.

Orlen says it will achieve a Net Zero target by 2050 for all three bands in which carbon emissions are measured.

Or, in simpler terms: in that year, all Orlen's emissions — those made in the production process, those resulting from the energy it consumes and produces, and even those related, for example, to the fuel it sells — will disappear or be neutralized by things like special programs meant to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Additionally, Orlen is saying it will lower its emissions intensity, which is how much carbon dioxide is produced per kilowatt. Orlen is pledging to reduce its activities’ so-called emission intensity by 40 percent in energy activities by 2030.

In other words, it’s saying that its power plants will produce 40 percent less carbon dioxide for each kilowatt-hour of energy used.

Orlen also says it will allocate 40 percent of its PLN 320 billion investment to specifically green investments.

If one added all three measurements together, Orlen’s 2022 emissions were equivalent to the carbon footprint of the entire transport sector in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Finland and the Baltics combined. And even so, these figures did not take into account the emissions of the PGNiG Group companies, which Orlen acquired in November 2022.

It was not until the second half of August 2024 that Orlen published revised group totals, which showed that, if PGNiG measurements were added in, emissions had actually fallen marginally from 2019 onwards, presumably as a result of the expansion of PGNiG’s gas-fired power plants. But according to this report, in order to reflect the scale of Orlen’s environmental impact, Austria, the Netherlands and Portugal would have to be added to the previously mentioned countries.

There is definitely ground for going green. But in reality, Orlen’s emissions are increasing, not decreasing.

Michal Hetmanski, co-founder of the Instrat Foundation, a think tank that deals with public policies, offers an explanation for this paradox. He and his colleagues are working on modeling what a green transformation of the economy should look like.

Hetmański explains that a significant advantage in the market allows Orlen to dictate terms, because big companies can do more. This is why the conglomerate has acquired other large companies in recent years: in 2022. Lotos, and in 2023. PGNiG. This has increased the group’s environmental footprint but raised its power in the industry. He also said that Orlen wants to run the last refinery in Europe.

What is the point of the “last refinery?”

“Decarbonization in Polish transport, the main fuel buyer, is slower than in other markets in Europe”, Hetmanski said.

In Poland, and the region in general, the green transformation is happening more slowly. For example, among newly registered cars in the EU, the percentage of electric cars is lowest in Central and Eastern Europe. That the transformation is happening more slowly means a a refinery can last longer in the region than elsewhere in Europe and even make it to a point when buyers of diesel or unleaded petrol are almost gone from practically all of Europe — but where there will still be a market for petrochemicals (e.g. for plastics) but no competition anymore. Without synergy between selling gasoline and petrochemicals, it is difficult to sustain a refinery.

What does this mean for Orlen’s environmental goals? They will not cut the branch they are sitting on, says Hetmanski. “It is in their interest to delay the transition, at least in the transport sector, and to promote so-called false alternatives,” meaning proposals that might look like they address climate change but in fact serve to steer away from solutions that would hinder business.

Full ahead on oil. Also: low emissions

One of Orlen’s promises is that the refinery, petrochemicals and mining will reduce their emissions by 25 percent by 2030 compared to 2019. On top of this, Orlen commits to reducing the emissions intensity (carbon dioxide produced per kilowatt) coming from its power plants. “According to our estimates, this will be around a 30 percent reduction in scope one and 12 percent in scope two,” comments Stanislaw Mroszczak, analyst at Instrat, referring to the first and second scopes. “This is not a very ambitious result in terms of the targets set by the European Union. However, a dynamic transformation is not easy to achieve in this type of company.”

And what about the impact of this promise on the third, largest scope, which takes into account all emissions linked to the company? Orlen’s pledge doesn’t acknowledge it.

Because of that, “This promise translates into an actual reduction of barely a few percent for the entire Orlen group,” said Diana Maciąga, a climate and fossil gas specialist at the Polish Green Network, one of the longest-established environmental organizations in Poland. “This is nothing more than a clever way of framing the issue to one’s advantage.

There is not much time left until 2030. And as the days, months and years tick by, according to the Instrat database, Orlen’s Plock refinery is the most emission-intensive plant in Poland. The promise of a 25 percent reduction is also undermined by the fact that — again according to Instrat data — Orlen’s Plock refinery has increased its emissions by more than 22 percent over 10 years.

And as for the promise to reduce emission intensity, “Reducing the emission intensity of energy production by 40 percent is not an ambitious target,” said Diana Maciąga. “Besides, it is a kind of creative accounting. No matter how many windmills and photovoltaics we put up, emissions do not fall by even a gram of carbon dioxide. They fall from stopping the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, not from increasing the amount of RES in the energy mix. How can this be explained most simply? Imagine putting a tablespoon of salt into a liter of water and then adding another liter of water. The amount of salt has not decreased, it is still a tablespoon of salt, although mathematically there is now only 0.5 tablespoons per liter of water.”

And even if Orlen were to reach its promised intensity reduction target by 2030, the company would still be producing energy with a greater CO2 impact than Spain, Portugal or Hungary today.

Gas is flowing, but also… leaking

When the world awoke to the roar of bombs falling on Ukraine on February 24 2022, Orlen faced a problem. It had to ensure a steady supply of gas without relying on Russia — which, up until then, had been Poland’s main supplier.

They made the change quickly. 2023 was the first year that Orlen did not import gas from Russia. The corporation trumpeted success. On BiznesAlert, Magdalena Kuffel, a specialist in gas contracts, predicted that Poland could become the largest importer of natural gas in the region.

The key to the change in the gas supply source was the Świnoujście gas port. It was there that, in 2023 alone, 62 tankers came to supply Orlen with 6.5 bcm (billion cubic meters) of gas, almost 46 percent of all gas imports. Two-thirds of these (41 vessels) came from the United States.

Today, few people are aware that the raw material Poland buys still has a dark side, even if Moscow does not make money from it.

Today, the United States is the largest exporter of gas in the world. The war, which is causing difficulties for European suppliers like Orlen, became a goldmine for the Americans. In 2023, more than half of their liquefied natural gas (LNG) was going to the Old Continent, and its sales to Europe were more than double what they were in 2021. Today, LNG brings in billions of dollars per month. Gas trade, which in 2015 did not even account for one per cent of US exports, accounted for nearly six percent in 2022.

Despite this, the United States temporarily halted the processing of new export decisions in January (the decision was quickly challenged by Republican states and suspended by a federal court in July). The reason? President Joe Biden’s administration explained that there were climate concerns. Regulations that were supposed to protect the environment and ordinary Americans were ineffective, and so the White House preferred to halt sales.

Six months earlier, a committee in the US House of Representatives published the results of a year-and-a-half-long investigation. It found that companies in the US were having a problem with large leaks from gas fields, meaning methane was escaping and becoming a significant part of the industry’s overall emissions. On top of this, companies do not use technology to reliably assess emissions, or, if they do, it is in a limited and inconsistent way. Internal industry documents show that actual emissions are much higher than those reported to the US regulator. Just one leak investigated accounted for 80 percent of the total emissions of the company reporting it.

Slate releases methane

The key to US gas power, and also to the sector’s problems, is shale. Over the past two decades, shale has gone from geological studies textbooks to the front pages of newspapers.

Shale gas is a gas like any other, but with a different extraction method. Traditionally, gas is extracted from sedimentary rocks. It accumulates in the form of “bubbles,” which, when drilled, begin to escape, making extraction easier.

Shale gas occurs in rocks with much lower permeability than sedimentary rocks. The bubbles it forms are tiny. To extract it effectively on a large scale, it needs to be flushed out with a mixture of water, sand and chemicals. This is known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. It’s a more expensive and complicated process than traditional methods. And it’s much more harmful to the environment

Poles had their own case of shale fever, one that broke out over the Vistula a dozen years ago. Emotions cooled just as quickly. It turned out that exploitation of Polish deposits would be much less profitable than American ones, to say nothing of the environmental costs.

It is precisely because of the geological and environmental risks that fracking has been banned in France, Denmark, Bulgaria, the Netherlands and Germany. In the USA and Canada, although it is still allowed, it causes controversy (in the USA, nearly 80 percent of gas comes from fracking).

Methane is responsible for a temperature rise of about 0.5 degrees since the start of the industrial era in the mid-nineteenth century (carbon dioxide caused a rise of 0.75 degrees over this same period of time). The reason why its impact on climate change is sometimes ignored may be due to its rapid decay time: it generally decays in the atmosphere over no more than 12 years. However, methane also retains much more heat than carbon dioxide — at least 100 times more at the time of emission and up to 80 times more over 20 years.

Hypothetically, it would be easy to slow down climate change by releasing as little methane as possible — but in reality, its concentration in the atmosphere is increasing. In 2019. The Guardian, citing researchers at Cornell University, indicated that a boom in shale exploitation could be responsible for accelerating climate change. The author of the study, Robert W. Howarth, suggested that the evidence could be the specific composition of methane in the atmosphere.

According to Zero Carbon Analytics, an international energy transition research group, the world’s largest companies have underestimated methane emissions by up to 94 percent.

Green eagle circling over the US

When asked about its US counterparts, Orlen Group claims it cannot share information because of trade secrets. This is strange as, for years, Orlen and other companies in the Orlen Group have been boasting about agreements with Americans, and information about foreign contracts has appeared publicly on Orlen’s and PGNiG’s websites and in the media

What do we know about Orlen’s activity in America? Since 2019, PGNiG, now part of the Orlen group, has been buying gas from Cheniere, the continent’s largest producer (their contract is valid through to the mid-40s).

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer of liquefied gas in the US, has been dogged by controversy. In 2022, a report came out that pointed out its greenwashing practices. Cheniere experts lied about the company’s methane emissions research methodology and cherry picked data to present Cheniere as less harmful to the planet. In the same year, Cheniere asked the US administration to exempt its ventures from regulations on carcinogen emission limits — the reason was said to be the threat of supply to Europe.

Orlen’s other major US partner is Venture Global, with which PGNiG signed an agreement in 2021. Together with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) we established that a total of 15 tankers from its subsidiary, Venture Global Calcasieu Pass, LLC, have arrived at the port of Swinoujscie since January 2022.

It, too, came under fire last year: according to a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, the construction of its Louisiana terminal took place at an accelerated rate at the expense of the environment. During construction, the company violated or circumvented (“deviated”) permits related to pollution and emissions more than 2,000 times. Fifteen shipments came to Poland from that Louisiana terminal.

Interestingly, Orlen sued Venture Global, but the reason was not environmental. The Americans simply reneged on their contracts. Instead of supplying Orlen with gas, they sold it to other companies, taking advantage of price increases. Orlen’s representatives claim that they did not receive any delivery in 2023, and it is possible that the situation was only changed when a tanker delivered gas from Louisiana to Swinoujscie in May this year.

Gas from another American contractor has yet to arrive in Poland. In January 2023, Orlen signed a supply contract with Sempra Infrastructure — part of the US company Sempra, which extracts gas by fracking. The contract is for 1.3 bcm of gas per year for twenty years. This is approximately 10 percent of Polish demand. The agreement to supply gas to Poland will allow the company to complete the construction of a transhipment port in Port Arthur, a city in Texas.

In a press release about the contract, Orlen characterized the American contractor as follows: “Sempra Infrastructure delivers energy to build a better world.” The information was reprinted in the same form by, among others, the Business and Climate section of the ‘Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, whose name translates to English as daily legal newspaper and whose advertising partners are Pepsico and Orlen.

Methane? We can’t say

What building a better world looks like is not a universal vision. Sempra‘s actions in the United States have led to the “Sempra is fracking our future” movement, led by the Californian organization San Diego 350.

“Around 80 percent of the methane produced by Sempra is fracked.Sempra has built a massive infrastructure to pipe gas from the Permian Basin (mostly fracking) to Texas and Baja,” Scott Kelley, professor of biology at San Diego University and a Sand Diego 350 volunteer, told us. “The impacts on human health and the environment around fracking are enormous. I was shocked at the levels of air pollution, water pollution and even radioactive waste it generates.”

““Fracking” is just one of a number of “unconventional” or more modern extraction methods for removing oil and gas from the ground that are toxic and destructive,” added Masada Disenhouse, director of San Diego 350.”That’s pretty much all that’s used today, given that all the more easily tapped deposits have already been emptied.”

The boom in US gas is not only the result of the war in Ukraine, but also of regulatory changes. Until 2016, gas exports from the US were banned.

The aforementioned Robert W. Howarth of Cornell University recently published a study in which he calculated the actual emissions of US gas along the supply chain. He estimated that if the carbon footprint of liquefying it into LNG, as well as transporting it (e.g. to Europe), is added to just burning the gas, the actual carbon footprint of US gas could be 28 percent to 46 percent higher than that of burning coal.

On top of that, there are leaks. According to scientists, methane leakage from the so-called Permian Basin alone — the region on the border between Texas and New Mexico from where gas will go to Sempra’s terminals — is the equivalent to the emissions that would come from burning coal that would fill 50 mile-long goods trains. Every day.

“If around 3 percent of methane escapes along the supply chain, the claim that replacing coal with gas is beneficial for climate protection is wrong,” said Diana Maciąga of the Polish Green Network.

Meanwhile, gas extraction in the region is set to increase further. By the end of the decade, it will rise by 50 percent compared to the amount extracted in 2021. The ongoing US presidential campaign is unlikely to help: some of the states where shale gas is being extracted are so-called “swing states,” where either a Republican or Democratic could win, meaning neither candidate or party wants to promise to cut down on something that helps the economy in those places.

In 2016, one of Sempra’s subsidiaries was responsible for one of the largest methane leaks in US history. Nearly 100,000 tons of the gas — which, again, has nearly 100 times the global warming impact of carbon dioxide — leaked into the Aliso Canyon.

None of this impacts Orlen’s operations. In 2022, it was one of the companies that declined to answer a question on methane emissions management in a survey conducted by the German organization Deutsche Umwelthilfe. The company’s press office claims that all long-term partners (Orlen also buys gas in so-called spot transactions, or, to simplify, on an ongoing basis, from the market) have environmental policies in place: “In the case of the US companies (in the context of shale gas), these are entities mainly involved in liquefying gas into LNG, they themselves in turn obtain gas on the US domestic market, which is a mix of production from different regions and carried out using different technologies that meet the environmental requirements there.”

And to translate: by spending billions, you can buy gas from that arm of Sempra or Chenin that “does the liquefaction” without going into the corporate intricacies.

“There is the UN’s Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 initiative, which introduces standards of good practice and emissivity of the highly damaging greenhouse gas methane throughout the value chain, for companies across the oil & gas sector. From extraction to transport, storage to use. Orlen is not a member, but Gaz-System, on the other hand, is. I believe that is intentional,” stressed Michal Hetmanski of the Instrat Foundation.’

Eagle lands beyond the Yukon

Orlen is not just buying shale gas. It is extracting it. It operates in the Canadian province of Alberta through its subsidiary, Orlen Upstream Canada. In 2015, it expanded its reserves there. In Alberta today, it covers about 1,400 sq km and has reserves allowing it to produce about 150 million barrels of oil and gas. This is several percent of Orlen’s total reserves and more than Poland’s annual consumption.

Nearly 95 percent of the daily oil and gas produced by Orlen Upstream Canada is the result of fracking. That’s the equivalent of 14,000 barrels a day, or, more than two million liters.

In 2023, Stanford University researchers discovered that it was fracking in Alberta that may have led to one of the strongest earthquakes in the Peace River region there (where two Orlen sites are located).

Fracking requires water. A lot of water. Alberta authorities estimate that between 0.12 and 0.45 barrels of water are needed to extract the equivalent of one barrel of oil or gas, depending on the length of time the field has been in production. Orlen in Canada uses hundreds of thousands of liters of it every day — in a region experiencing the worst drought in a quarter of a century.

“Alberta can be criticized as not being strict enough when it comes to gas and oil regulation,” said Martin Olszynski, a lecturer at the University of Calgary and environmental law specialist. “The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) doesn’t require companies to post security for future clean-up, and there is no fixed deadline after a well becomes inactive that it needs to be cleaned up. The result is almost 80,000 inactive O&G wells on the landscape, with total estimated liability ranging from $30-80 billion (CAN). ”

Orlen owns 60 such inactive wells (it receives subsidies from the Canadian government to clean them up). Another two will cease to be active at the end of this year. This is not much, and, certainly, Orlen is not among the worst polluters. The local environmental agency has not raised concerns with Orlen. The scale of the company’s operations is small in Canada.

However, there is something that makes Canadian Orlen’s “green energy” a dream: the emissions performance of gas production in Canada today is on average four times higher than that allowed by EU regulations.

Orlen defends itself by saying that it complies with Canadian regulations and is investing in a program to reuse water used for fracking.

Green… or at least low-carbon

Despite objections from European countries, including Spain and Denmark, natural gas has been considered a low-carbon fuel by the EU for several years. This is what allows Orlen to tout that “around 70 percent of its electricity production comes from zero and low carbon sources.”

We asked Chat-GPT 4 how much of Orlen’s energy is generated from renewable sources. The machine was fooled: it quoted a PR figure of 70 percent. When asked a more specific question (“non-gas generation”), after analyzing the company’s 200-page report for 2023, it gave a different figure: around 25-30 percent.

The program got it wrong. The information we wanted can be found in the same report with the help of a calculator. This is because Orlen gives the total energy capacity (5.5 GW) and thermal capacity (13.9 GW), and their what of it comes from green energy sources (0.9 GW energy capacity, 0.2 GW thermal capacity).

In this energy mix, the actual share of renewables is 16.5 percent and 1.5 per cent, respectively, well below the estimates of Chat GPT 4. These figures are only explicitly stated in the report for the first quarter of 2024.

In recent years, Orlen has been investing heavily in gas-fired power generation. Two more units are currently under construction — in Ostrołęka and Grudziądz. In its strategy, the company promises to more than double its current gas capacity, to 4 GW. The result? “Between 2022 and 2023, energy production from heat and gas in the Orlen group increased by 50%,” says Stanislaw Mroszczak, a specialist from Instrat. “But methane emissions were already three times higher than in 2022.”

Orlen asserts that the carbon footprint of natural gas is almost half that of hard coal, and its power plants are newer and more efficient.

“The question is who should decide to replace coal with gas?” asks Michał Hetmański, the CEO of Instrat. “Not Orlen, not other companies, but the ministry. For the last few years it did not decide, because the ministry’s management sat in the pockets of the CEOs of state-owned companies. Let’s hope this does not happen again.”

There is an ongoing debate in Europe as to whether allowing gas to be considered as a low-carbon fuel in sustainable energy mixes has been counterproductive. According to some experts, it has set back the development of renewable energy and enabled large-scale greenwashing. In May, legislation was introduced in the EU to track leakage and methane emissions — but it only applies to EU territory. Tools to regulate the carbon footprint of imports will be introduced after 2030, by which time Orlen will be “green” and low carbon, regardless of what its partners and the company do in America.

But perhaps better “dirty” gas than supporting Russia? “This is a political argument, not an environmental one,” noted Disenhouse. “Is it better to get the plague or the smallpox? The best way to move away from the need to import fossil fuels is to develop renewable energy sources.”

Poland currently consumes around 18.4 billion cubic meters of gas, but demand for gas in the electricity sector is only just beginning to rise. According to forecasts by Gaz-System, the Polish gas transmission system operator, it will rise to 27.5 bcm in 2032.

“When we reach this ceiling, another problem will arise,” explained Hetmanski. “It will no longer be profitable for Orlen to build green energy capacities, because this will mean that it will stop making money on gas. And therein lies the problem with the whole idea of a multi-energy concern — it wants to make money on what it has the biggest margin on.”

New technology, new problems

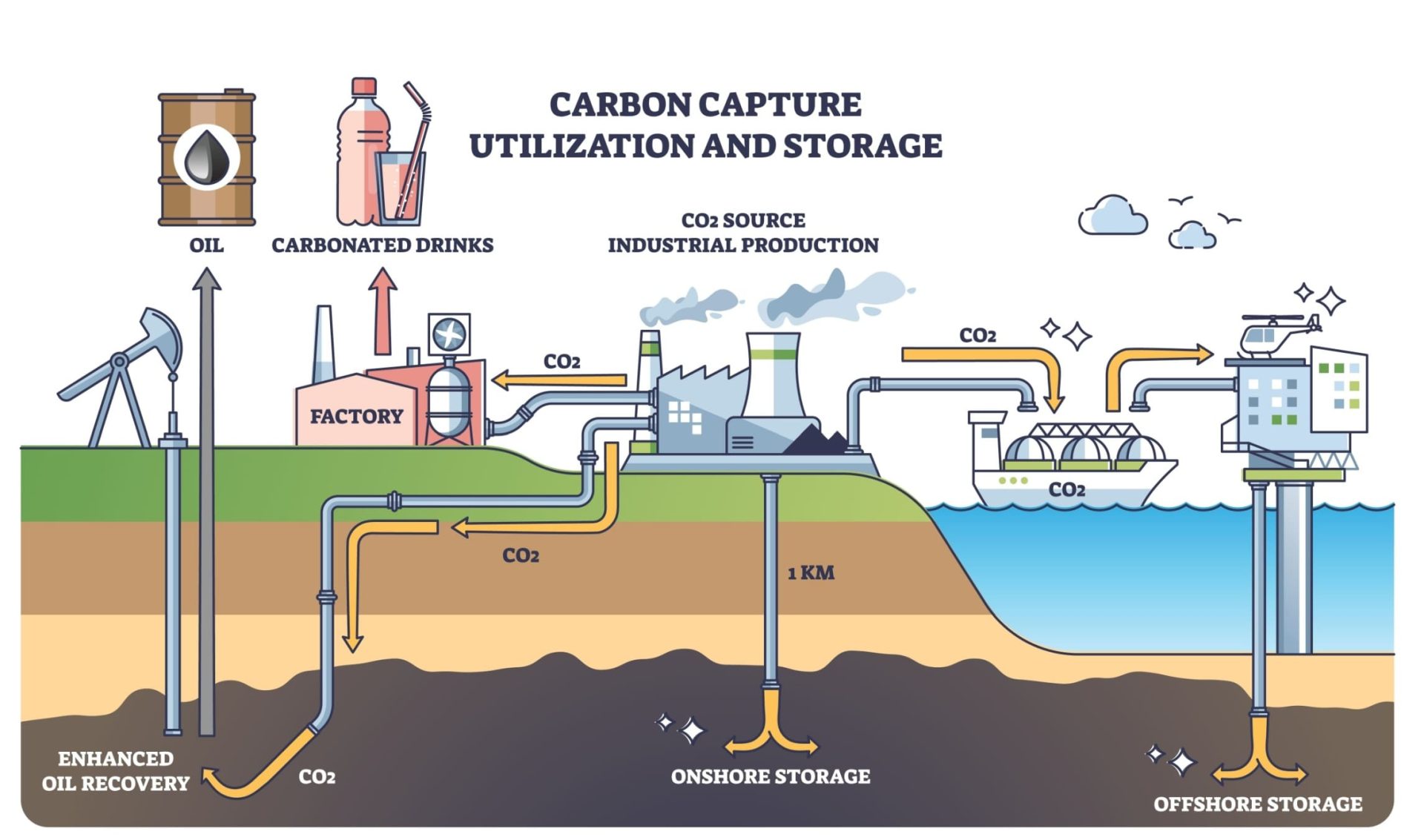

One of the Orlen Group’s big “green” projects is the mysterious-sounding CCS. It stands for Carbon Capture and Storage and is the idea of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. In CCS, carbon could be stored, for example, underground — in places where we have extracted gas.

PGNiG Upstream Norway is another of Orlen’s subsidiaries. At the end of last year, it acquired a half share in a Norwegian CCS project called “Polaris” in the Barents Sea. The purchase was expected to allow a total of 100 million tons of carbon dioxide to be pumped into the seabed north of the Norwegian coast. This is four times the group’s first scope emissions in 2022.

The project was due to start by the end of the decade and was supposed to enable the pumping of around 3 million tons of carbon dioxide per year. Its cost was estimated at around a billion dollars.

If the project had gotten off the ground, the group would indeed have had a chance at climate neutrality, at least on paper. With the Net Zero concept, climate neutrality does not mean that the company actually has to reduce the amount of dioxide it emits. All it has to do is invest in projects that offset the amount of carbon dioxide — such as CCS. So it can continue to produce oil, simply subtract the value of the reduced gas from the value of the emitted gas, and say it’s gone green.

It is CCS that was to be a major part of reaching the target to reduce the carbon footprint of refineries, petrochemicals and mining by 25 percent.

But as the result of an audit, Orlen withdrew from the Polaris project. According to the Polish edition of Business Insider, the return on investment was unsatisfactory and the storage capabilities were lower than initially anticipated. Orlen has not disclosed how much it has spent on the project, which turned out to be a failure. In response to our questions, they stated that “the amount was within the lower range of standard expenditures for such projects.”

According to findings by Business Insider journalists, Orlen does not intend to abandon CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) and still plans to achieve the capability of storing 3 million tons of carbon dioxide annually by the end of the decade. In a response to Frontstory.pl, Orlen’s press office claimed that the knowledge gained could be utilized in other CO2 storage projects on the Norwegian Continental Shelf.

Shut up and forget for thousands of years

The concept of CCS has been gaining momentum of late. Carbon dioxide is captured at the production stage, then liquefied, transported (e.g. by pipelines or tankers) and pumped underground, usually into so-called pockets that form at the bottom of the sea after gas or oil extraction. There, the carbon dioxide is supposed to be harmless.

The snag is that CCS requires liquefaction stations, transport ships, pipelines, pumping stations, i.e. investments that cause large emissions. “Keep in mind that carbon capture technology requires massive amounts of power in its own right just to operate, circa 20% to 33% of the power output of the station trying to be cleaned up,” noted Grant Hauber, an analyst at the US think-tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

That is, instead of reducing emissions, we will be increasing them — we’ll just be pushing these greater amounts underground.

“Further, net capture rates of such plants, based on empirical evidence, is not the over 90 percent theoretical rates claimed by proponents – it has run between 50% to 80%,” said Grant Hauber.

Research by Stanford University scientists a dozen years ago suggested that large-scale carbon storage is difficult and dangerous. Injections of the gas into rocks can lead to tectonic movements, which in turn can unseal pockets of the gas that will return to the atmosphere. While there are places where this risk is minimal, you would need to find several thousand of them to make a real impact on climate change. This is unlikely to happen.

Last year, Energy Economics and Financial Analysis published a report, showing that the two Norwegian projects that sparked the global CCS boom, Sleipner and Snøhvit, are at risk of leaks. Snøhvit is located in the Barents Sea, close to the Polaris project and – possibly – other projects Orlen now intends to look into.

Speaking to the Scottish investigative editorial The Ferret, Erik Dalhuijsen, an engineer with several years’ experience working on CCS, pointed out that carbon dioxide needs to be locked underground for 10,000 years or so before it hardens (that is, it stays in the rocks until it starts to react chemically with them) and stays there forever.

“Don’t look up” at the bottom of the sea

As Grant Hauber, co-author of the IEEFA report put it, “In the last year, proponents of CO2 storage projects have attempted to advance their development. Northern Lights in Norway is perhaps the most tangibly advanced of all of them. They are looking to start with small volumes of CO2, totalling about 1.8Mt/yr. However, at such rates, this effectively remains a demonstration project.”

Hauber is keeping a close eye on how technology providers are responding to the hassles and risks associated with CCS. “Uniformly, it has been a story of having to adapt or even create new technological solutions in order to address the harsh conditions CO2 imposes on equipment. CO2 is highly corrosive when exposed to even trace amounts of moisture, thus requiring special metallurgy. Well casings and heads require special designs to maintain seals under the conditions imposed by highly compressed CO2. All the valving and safety mechanisms that many thought could be “simply” transferred from oil and gas production operations are having to be redesigned and developed to meet wider ranges of temperature and pressure conditions specific to CO2 handling.”

This technology also has another dark side: as an odorless gas, carbon dioxide gives no signal of leaks.

According to Hauber, the CCS industry is in the research and development phase, although many are trying to sell it as a mature, developed sector. “Reality will take its revenge on those who promise 100 percent safe, reliable and leak-proof projects in the contracts they sign today. Their costs will rise, the risks will remain,” said Hauber.

A dozen years ago, a CCS project worth EUR 600 million was being prepared by the Polish PGE energy group in Bełchatów. It eventually withdrew from the plan.

Orlen’s press office responded to our request for comment by writing that carbon capture and utilization (CCU and CCS) are key decarbonization projects. It wants the carbon dioxide from the company’s production to be used, among other things, as a raw material for specialized petrochemical products, building materials, etc. It is conducting its own research on this.

In the film Don’t Look Up, a powerful businessman decides to risk humanity’s existence. Instead of destroying an asteroid hurtling towards Earth, he tries to capture it to make money from the minerals on it. According to science journalist Laura Hiscott, this is an obvious parallel to big business investing in CCS.

“It is worth not resigning from the technology in itself. In those sectors that find it difficult to move away from carbon emissions, it may be needed,” said Michal Hetmanski of Instraat. “For example, cement production.” But that’s a far cry from considering CCS the future of green energy. “Certainly in the electricity and heating sectors it doesn’t make sense.”

Doctor says turn off the tap

One of the leading programs that Orlen boasts about is Planet Energy. This has been an ongoing initiative in Poland since 2010 and is intended to help children “better understand the world of energy around us, the impact of our behavior on protecting the environment or promoting sustainable development.”

The latest, twelfth round of Planet Energy ended a few months ago. As part of the program, children are taken on a virtual scientific expedition by PhD Tomasz Rożek, a well-known science communicator and the founder of a foundation that popularizes science.

Planet Energy’s materials, which can be found online, mention fossil fuels and different ways of obtaining energy. They cover solar and renewable energy. But Planet Energy does not once mention climate change. The textbooks, lesson plans and interactive materials show that the disadvantages of fossil fuels are first and foremost that they can run out, on top of which they generate waste and pollution.

“It is difficult to say to what extent these omissions have been made on purpose,” said Dr. Zbigniew Bohdanowicz of the Foundation for Climate Education. “This campaign is part of activities that are good in themselves, but do not solve anything. Turning off the water, cleaning up the forest, feeding the birds? In the context of the existential threat that the climate crisis poses to us, treating such actions as the answer is absurd, it is trivializing the problem. I have a nine-year-old son, I think even he would understand that these are not actions adequate to what we are facing.”

The authors of Planet Energy, for example, do not see fit to inform children that the current concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is 50 percent higher than before the industrial revolution and that this rise was induced by humans. Even under a moderate warming scenario, tree species that currently make up 75 percent of the forest area will disappear from Poland within a few decades. Planet Energy does not even mention that the planet is warming.

“It makes it seem as if the intention is to channel people’s energy into side activities that will not disrupt the direction of the economy,” said Bohdanowicz. “It’s also a way of fighting activism: to give those involved a marginal occupation that won’t get in the way. Meanwhile, we need to focus on systemic solutions, on regulations, on how to collectively reduce the total pressure on the planet, not focus on individual actions, because that’s not how we’re going to fix climate and environmental problems.”

Too much for the children

On its website, Orlen reports: “With future generations in mind, Orlen is implementing a range of social activities.” Back in the 2022 report, the company wrote that Planet Energy is meeting UN Sustainable Development Goal 4: “Good quality education.”

The authors of Planet Energy suggest that, after undergoing the lesson “Where does electricity come from?,” ”the child knows what electricity is (gives, in their own words, a definition of electricity, e.g. Electricity is the orderly movement of electrons from one place to another).”

Why doesn’t Orlen make pupils aware that burning fossil fuels leads to a warming of the planet? “No one wants to leave their children depressed,” acknowledged Dr Bohdanowicz. “But we need to think seriously about what we are aiming for, how important our current actions are for the future. We live in a world that is changing and will continue to change, but how — depends on what we do.”

“The Planet Energy programme has been granted honorary patronage by the Minister of Climate and Environment in 2022 and 2023 and assessed as meeting the conditions described in the rules for granting honorary patronage at the time,” the Ministry of Climate and Environment said in a comment.

Asked about the absence of climate change issues in Planet Energy, the Orlen press office responded with a letter two pages long. It is simply a description of the program. One sentence directly addresses the question: “Global warming is also one of the potential topics of the next editions of Planet Energy.” Energa, which manages the programme, replied that it focuses “on smaller thematic units” and points out that climate change has been mentioned in Facebook posts.

The team of the Science Foundation. I Like It received our questions on 23 July. By the time of publication, despite assurances that they had been forwarded to Tomasz Rożek, we had not received a response.

The world’s most ethical company

Between 2014 and 2021, Orlen was listed among the world’s most ethical companies eight times by the US-based Etisphere Institute. The entity making the list is an ordinary, profit-driven company, the main activity of which is the publication of a quarterly magazine on ethical business, as well as the aforementioned list. As Orlen reported in 2021, it was the only one recognized in this way in the whole of Central and Eastern Europe.

Over the years, top Polish online outlets such as Bankier.pl, “Rzeczpospolita,” Forsal.pl and WNP.pl have all shared this information.The Ethisphere Institute’s list was attractive for image and communications purposes, all the more so because it included companies such as Volvo, Sony and IBM.

The potential conflict of interest surrounding the list was reported as early as 2014 by the Los Angeles Times, which shared that the ability to use the “World’s Most Ethical Company” logo cost $10,000 at the time. “There was no cost to Orlen to submit to the assessment,” the institute’s press office said. It continued, “If the awarded company wanted to use The World’s Most Ethical Company logo on its website (…), in the company footer, publications, etc., this involved the cost of purchasing a license to use the logo (dependent on the fields of use).”

Orlen did not answer whether it bought such a license or for how much.

A dozen years ago, the “World’s Most Ethical Company” included a company that had a short time before paid a fine for violating environmental regulations. Last year’s gala included a subsidiary of a supplier of drones and military equipment to the Israeli army, which touted its missiles as the answer to the challenges the country’s soldiers are facing after October 7, including in Gaza.

Retirement fund from a destroyed planet

Valued at around PLN 65 billion, Orlen is primarily accountable to its owners. Nearly half of it is owned by the Polish State Treasury. With such an advantage in shareholding, this means it is the state that can change the direction of the company, including in terms of environmental protection and the fight against climate change.

Just what happens when the state mixes in?

“So far, Polish regulations for the gas and oil sector, or those EU regulations actively co-created by the Polish government, have been de facto created by Orlen,” said Michał Hetmanski of Instrat. “We need to distinguish between a healthy dialogue between the ministry regulating the sector and specific companies and representing the interests of the largest player outright at the expense of the rest of the market, including consumers. For years there has been a large and growing gap between the competences of the two sides of this table. Regulated entities, including Orlen, have profited from low salaries in the administration and the loss of the civil service ethos by regularly acquiring employees leaving ministries.”

Moreover, Orlen is considered a political asset by whoever’s in power: whoever is in government has access to a company with potential for high salaries, unlimited ability to stuff relatives and friends into the company, nepotism. In practice, this means that the company has an easy explanation every time there is a change of government: we are not doing anything about the climate because of the mistakes of the previous administration.

However, the State Treasury is not the only shareholder in Orlen. The next seven largest shareholders are the Open Pension Funds (OFEs), which together hold shares worth several billion zlotys. For each of them, Orlen was the largest or second largest investment in Poland. This means that the financial future of millions of Poles is largely dependent on a company from the fuel sector that has a negative impact on the future of the planet.

UNIQA’s open pension fund serves more than one million people and holds Orlen shares worth nearly PLN 800 million. Maciej Krzysztofek, spokesman for UNIQA, does not want to talk about climate policy: “In implementing the intentions of the investment policy, UNIQA OFE strives to achieve the maximum degree of security and profitability of the investments made,” he wrote back to us in an email.

“When making investment decisions concerning PKO Otwarty Fundusz Emerytalny, we do not take into account risks for sustainable development, nor do we consider the negative impact of investment decisions on sustainable development factors” admitted Dorota Świtkowska from PKO BP. Orlen is the largest position, worth around PLN 600 million, in their open-ended pension fund, which secures the future of almost 850,000 clients.

“We do not comment on our investment activities” said Bohdan Białorucki of Allianz, which has over 3 million clients and Orlen shares worth PLN 3.3 billion. “We are fulfilling the goal set for all OFEs by the legislator. The overriding principle of OFE investments is to achieve the maximum return on investment while keeping the investment as safe as possible.”

Stanisław Mroszczak of Instrat deals, inter alia, with sustainable finance, i.e. how companies achieve environmental and social goals. He examines the reports of companies such as Orlen on a daily basis: “However, funds should also invest in ‘dirty companies’ so that they feel the growing need to decarbonize. Investing in already ‘green’ companies has less potential to have a positive impact on the overall decarbonization of the economy. However, a lot depends on regulation here — financial companies are reluctant to invest in transition investments of carbon-intensive entities because they know that their own value chains will also be negatively affected. This is where, firstly, the regulator should come into play, promoting this kind of solution, and secondly, entities that are not fully covered by market logic, such as open pension funds.”

From 2020, the year Orlen announced its landmark sustainable growth strategy, to 2023, the company has shown PLN 116 billion in EBITDA and paid out more than PLN 14 billion to shareholders.

Orlen has announced updates to its strategy for the next few years, reviewing projects and investments. These, however, will not change the fact that it will remain a multi-utility conglomerate. Green Eagle will have the largest profit margins on fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, Poland has until 2026 to introduce the legislation necessary to implement the EU directive on greenwashing, among other things. Perhaps by then Orlen will also have been investigated by the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Tadeusz Michrowski is an editor and fact-checker at VSquare and FRONTSTORY.PL. He is an award-winning journalist and writer.