In late February, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan, decided to open an investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Russians and Belarusians in Ukraine. An eventual trial at the ICC in The Hague would be a complicated affair, possibly lasting several years.

This article was originally published in Czech on investigace.cz

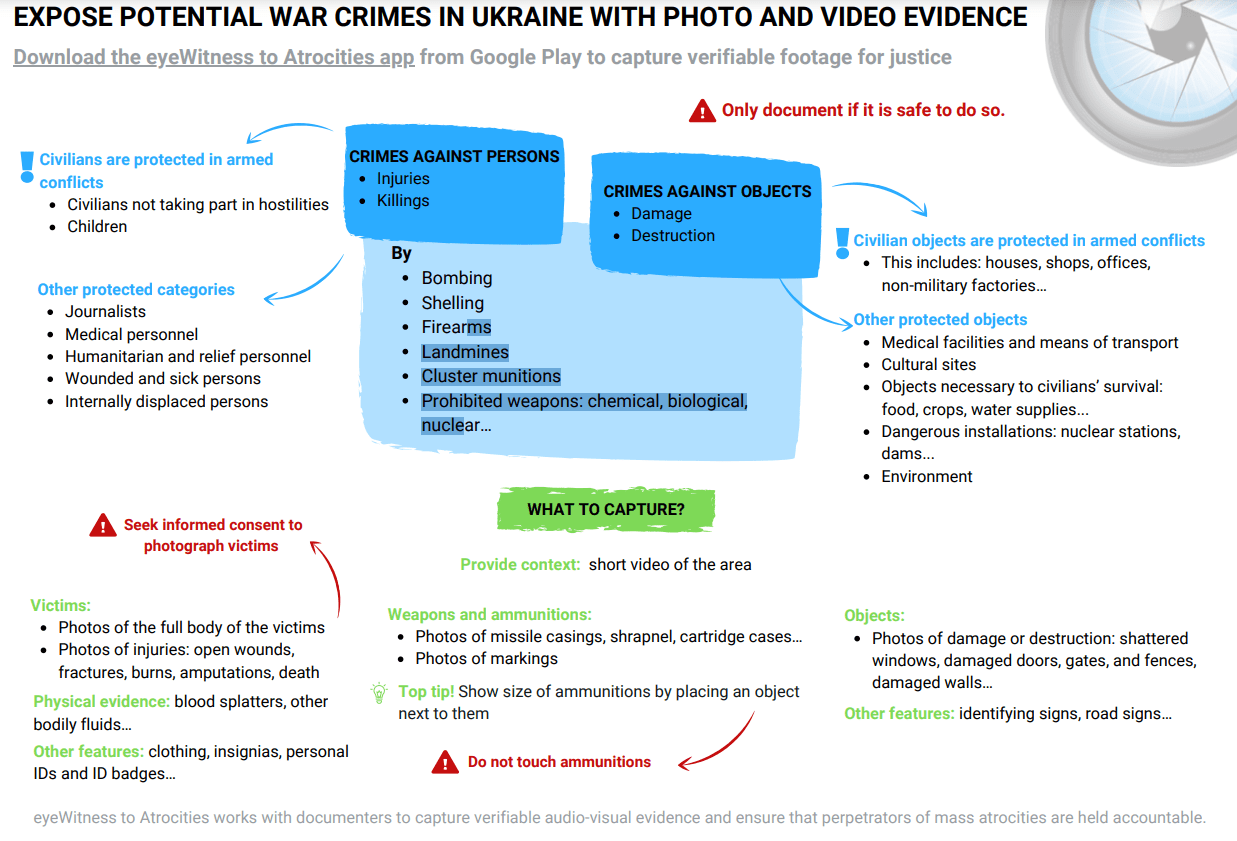

Civilians can get involved in the initial phase of evidence gathering. In this regard, the non-profit charity EyeWitness launched a Ukrainian version of a special app for collecting evidence of alleged Russian and Belarusian war crimes at the beginning of March. Videos and photographs taken through the app could become relevant pieces of evidence in The Hague.

What does an ICC trial look like?

Proceedings before the ICC are usually long and divided into several phases. The first step includes a preliminary examination. The request to open investigations must then be granted by the Pre-trial Chamber. Subsequently, the prosecutor writes an indictment, and only then does the main trial begin.

In some instances, for a case to go before the ICC at all, the Prosecutor must first open a so-called preliminary examination. The goal is to determine whether the evidence that may be presented to the court in the future meets the admissibility requirements. The Prosecutor for exampleassesses whether the information obtained suggests that the alleged crimes fall within the jurisdiction of the ICC, namely, whether crimes genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, or crimes of aggression have been committed.

If the prosecutor assesses during the preliminary examination that there is reasonable basis to launch an investigation, he must usually first ask for approval from the Pre-trial Chamber. If the Pre-trial Chamber grants the request, the prosecutor will open the investigation and later bring charges against individuals, such as the main commanders of the Russian armed forces.

A request for an ICC investigation was already submitted by Ukraine on 25 April 2014, citing the crimes committed during the Maidan demonstrations in Kiev at the time. It later made a similar declaration regarding the annexation of Crimea. This preliminary examination lasted for six years, ending in December 2020, when the prosecutor concluded that the crimes committed were admissible and fell under the jurisdiction of the ICC.

In addition to the Prosecutor’s current request, 39 other states have joined in asking the ICC to look into the current military conflict. Lithuania was the first country to ask the Court to investigate not only Putin’s inner circle, but also that of Lukashenko.

In late February 2022, Prosecutor Karim Khan decided to open an investigation into the overall situation in Ukraine. The court is thus expected to focus not only on the crimes committed during the Maidan demonstrations, but also on the current situation in Ukraine.

The ICC, however, will not investigate Russia for crimes of aggression. As Zuzana Drexlerová, an international criminal law analyst at The Hague, explaines, “In order for the court to deal with the crime of aggression, both parties to the dispute must be members of the Rome Statute and would have to sign the Kampala Amendments on the crime of aggression. Neither Russia nor Ukraine meet either of these conditions, so the ICC cannot deal with aggression. Alternatively, the UN Security Council could make a referral, which in practice will not happen, because Russia has veto power in the Security Council.”

The ICC will thus deal with crimes against humanity and war crimes, which can only be committed by individuals.

“For now, there is no indication that the Russian side committed the crime of genocide. It is difficult to say what direction the conflict will take. We are only at the beginning. However, Putin mentioned in his speech that the Ukrainian people do not exist,” Drexlerová clarifies.

There are no time limits on how long the different stages of the trial should last. The length of trial depends on the circumstances, complexity and seriousness of the alleged crimes before the court, and length of the investigations. However, the time should be reasonable and the accused should have the right for a fair trial without undue delay.

“The situation in Ukraine is unique because the investigations before the International Criminal Court are underway during the conflict, right from the beginning of the war. Therefore, I estimate that the main investigation will take a shorter period of time than usual, but we are still talking about years,” says Drexler.

Who’s collecting evidence?

During the preliminary examination, which can last years, only the prosecutor collects evidence. Although, in addition to the Prosecutor, gathering evidence may also be initiated by individual groups, NGOs, or countries that accept the jurisdiction of the ICC. Once an indictment is issued, the defense, which also has its own investigators, starts collecting evidence as well.

Who defends the accused?

The lead counsel has a team of lawyers experienced in defending cases. The court has its own list of defense lawyers from which the lead counsel is either chosen by the defendant or assigned by the court. The defense lawyers do not have to be nationals of a state party to the Rome Statutes of the ICC. For example, many of them are from the United States. The lead counsel formsa team, which usually includes two co-counsels, one or more investigators (usually from the defendant’s country of origin), legal officers and their assistants, a case manager, analysts, and translators. The number of team members depends on the budget, but is usually around ten.

The work of the prosecution and defense is paid for by contributions from member states and voluntary contributions. The prosecution team averages around twenty people, the defense team, around ten.

The ICC does not set any precedents, and there is no uniform scale of possible punishments. There is only an upper limit to prison sentences.

“The maximum possible sentence is a life imprisonment even though in practice it is rarely above 30 years imprisonment, and that is in the case of the most serious crimes. That could be what Putin or Lukashenko could face. It all depends on the gravity of crimes committed and aggravating factors,” says Drexlerová.

Examples of such crimes include placing landmines; restricting access to water and electricity; attacking a nuclear power plant; deliberately killing civilians; forcibly transferring populations; torturing people; attacking civilians, schools, hospitals, or maternity hospitals; and killing prisoners.

The prison-sentence length depends on the gravity of each crime. The court takes into account factors such as whether a single building was bombed or an order was given to bomb an entire city, how many civilians died, whether the defendants acted under duress, or whether there were mitigating circumstances. For example, an indicted general may argue before the court that he was unaware of why he was going to Ukraine. Attacks on maternity wards or hospitals, however, are serious enough that those on trial will ultimately be handed higher sentences.

“Defense counsel may decline to represent Russians. Personally, I wouldn’t sign up in cases where war crimes are obvious. But I stand for the right of every defendant to have a fair trial and effective defense, even if I cannot imagine myself ethically defending one of the top generals of the Russian armed forces. In such cases, the defense is mainly based on procedural law and is limited to whether the evidence was obtained legally,” says Drexlerová.

Civilians can collect evidence of war crimes

Non-profits, individuals, or countries may also be involved in collecting and presenting evidence. Right now, the Ukrainian case is at the stage of investigations and the information collected will serve as supporting material for the prosecutor.

One non-profit charity that is helping gather evidence is eyeWitness, which has developed a special application for collecting audiovisual material that should be sued in court as evidence. Witnesses to alleged war crimes can record photos or videos of them using this specially secured app.

“The app is designed to be very simple to use. Our website provides step-by-step instructions – how to download the app, take a photo or video, and then upload it. The app doesn’t do anything else. The users can add notes if they want, and that information is very helpful, but it’s not necessary,” says Wendy Betts, director of eyeWitness.

How the app works

The app is based on three pillars: it collects data about the time and place where the footage was taken, then encrypts the footage so that no one can tamper with the data, and assigns a special alphanumeric code to the footage. If someone were to try altering photos or videos captured with the app, the unique code would change.

Determining the time and place evidence is collected

The app creates a record of precise geographical coordinates using GPS and satellite data. Therefore, for eyeWitness to work properly, the user’s mobile phone does not need to be connected to the internet. In addition, when a photo is taken, the app records all nearby Wi-Fi networks. Likewise, it also collects data about the cell towers that are responsible for transmitting and receiving radio signals from the mobile phone. In this way, exactly where evidence is collected can be determined from three different sources independent of each other, none of which rely on the mobile user.

Integrity of the footage

After the app user takes a photo or video, the footage is stored in an encrypted format inside the app’s gallery. Because the footage is encrypted, it cannot be edited by the user. The gallery itself also has no photo editing features. Photos and videos taken with the app are not stored in the phone’s standard gallery and therefore are not kept anywhere outside the app’s secure system.

A unique alphanumeric code

At the moment a photo is taken, the application uses an algorithm to calculate a so-called hash value, a digital fingerprint. The image is then assigned a unique alphanumeric code based on the pixel value. Any modifications to photos or videos taken would change the hash value.

Images and video cannot be taken with a conventional camera and then uploaded to the app; only a mobile phone with the eyeWitness app installed can be used. The app sends the encrypted image or video to eyeWitness servers, which verify that the uploaded data was captured using the app.

The images and videos are stored on a non-public server that acts as an evidence repository. To catalogue these audiovisual materials, eyeWitness employees attach labels to the uploaded photos and videos. They can also describe what these materials depict to simplify future searches.

To ensure that an app user recording war crimes does not draw unwarranted attention, the app settings can be changed so that the interface is reminiscent of a regular phone camera. Thus, no one else will know that the eyeWitness app is being used. The app also features an emergency button; if a user is worried their phone might be confiscated, they can press this button to delete the entire app immediately.

Evidence in court

For these recordings to be used as evidence in a criminal trial, they must meet two requirements: they have to be relevant and credible. The app ensures that images and footage are credible, but it is up to users to determine if they are relevant. For example, when an evidence collector wants to record that a house was bombed – human dwellings are protected by international law – one video alone is not enough to convince a court that a war crime has been committed. The relevance of the evidence is assessedin the context of other evidence. Therefore, eyeWitness has produced a guide for how to best capture images of potential war crimes to increase the likelihood of such evidence being relevant to criminal cases.

EyeWitness manual

The app has been running since 2015, and currently there are more than 15,000 images and videos from all over the world in the eyeWitness database. On Tuesday, 8 March 2022, the non-profit eyeWitness also introduced a Ukrainian version, as interest in the app has increased in recent weeks in war-torn Ukraine.

If the user does not wish for their identity to be revealed, the app can collect data anonymously. Some people, however, create a nickname, while others use their own name.

“The idea behind the app was to collect information that could be authenticated up to court standards. We designed the app in consultation with legal professionals and created a way to easily verify the footage. In addition, we significantly enhanced the security features of not only the app itself, but also its user. The images are hidden so they will not appear in the standard gallery of the user’s phone. Moreover, the user can choose a secret password to access the app’s gallery. The password-protected gallery also has a [special] feature; if the user [enters] a wrong password, the standard phone gallery will open. So it doesn’t give an “incorrect password” message. It looks like it’s correct. It just takes the user back to the standard gallery, where the sensitive photos are not stored. It does elevate the level of the security, when users, for example, cross checkpoints. That’s our added value,” explains eyeWitness director Wendy Betts.

Eva is a journalist working for investigace.cz based in Prague. Investigace.cz is NGO covering organized crime topics and the only Czech partner of OCCRP. She works on projects connected to Slovakia.