By Tomáš Madleňák and Lukáš Diko, ICJK

Slovak authorities underestimated the second wave of the pandemic and walked straight into it, unprepared. This resulted in the implementation of the PM’s megalomaniac ambition of testing the country’s entire population. More than 3.5 million people were tested in a programme developed in just two weeks. Hundreds of thousand people in more than 40 regions have been tested repeatedly over this weekend too. Experts argue that the government underestimated the threat and failed to use the time it had to prepare for the second wave.

September 16, 2020: “BRIDES, EVERYTHING’S GONNA BE ALL RIGHT,” wrote Slovakia’s PM Igor Matovic in a Facebook post, signalling he would overrule the decision of the state’s Pandemic Committee, which, due to a rising number of COVID-19 cases, decided to limit the number of wedding guests to a maximum of 30 people.

Source: www.facebook.com/igor.matovic.7

On October 17, 2020, PM Matovič announced an unprecedented plan to carry out mandatory mass antigen testing in an attempt to stop the second wave of Covid-19 and avoid countrywide lockdown. He later admitted that it was his idea to test the country’s entire population using antigene tests. On the day of the announcement, 1,968 people tested positive, or 16.5 per cent of those who turned up to take the swab.

“We have 2,000 new cases a day. That’s our average. During the first wave in the critical months of April and May, we had an average of 20 cases, or – to be precise – 19.8 cases a day. Twenty against two thousand. […] Of course, we have made mistakes, but who would have thought that the second wave would be ten times bigger than the first one. I thought it might be twice as big, and now it’s a hundred times bigger. Today, we do realise that eventually, it is going to be 200 to 250 times bigger than the first one and if we can consider ourselves lucky if we have 5,000 new cases. Let’s keep our fingers crossed,” said Matovič when asked about political responsibility.

On October 31, 2020, just two weeks after the plan to carry out a nationwide testing programme was conceived, millions of Slovaks showed up at local testing points. We decided to visit the testing point in Ruzinov, one of the largest suburbs in Bratislava. When we saw dozens of people queuing up to be registered, we initially wanted to go back home. There were exactly 89 people ahead of us. But those who have already been swabbed told us the waiting time was not that bad. We decided to stay as the temptation to see results after around 15 minutes was hard to resist.

“They have around five healthcare workers collecting the swabs. I spent four hours at a drive-through collection point but eventually gave up and came here, and waited only about an hour,” said an elderly gentleman who is happy that both he and his wife have been issued certificates proving they tested negative. Such certificates would allow them freedom of movement, as the country has the authorities have imposed partial lockdown.

The wait was not particularly bothersome, since everybody socially distanced themselves, [wore face coverings] and generally were in good spirits.

Not so long afterwards, a young couple walked by with their toddler in a pushchair. A policeman asked them whether they had already been tested and when they shook their heads, he lifted the tape and let them jump the queue to register for the swab. Nobody protested and the crowd praised the move.

On the other hand, the mood at the drive-through point, where people were largely irritated, was rather sour. Another policeman divulged that they had to wait for medical staff to arrive until 8 a.m. and then a technical glitch prevented them from going ahead with the swab until 9 a.m. Testing points were supposed to have opened at 7 a.m. Some of the people had to sit in their cars for more than five hours.

Having presented their IDs, those queuing up were issued a registration number and then a medical worker in a hazmat suit collected a sample. Afterwards, they proceeded to the waiting area. After 15 minutes or so another volunteer brought envelopes that contained results of the test.

Last weekend, over 3.6 million people were issued blue certificates, part of a nationwide test. Over 38,000 Slovaks tested positive and had to quarantine at home. Although children under 10 and people over 65 were not obliged to be tested (still, many chose to take the test anyway), it looked as if that the goal of testing the country’s entire population (or rather, a sizable part of it) has been achieved.

But this wouldn’t have happened had Slovak politicians used the summer to prepare for the second wave and listened to experts and not brides that lamented they would need to postpone their weddings.

Lazy summer recess

“This situation is a result of relaxed restrictions and high mobility in the summer. When the Pandemic Committee (PC) wanted to step in and adopt stricter measures concerning travel and holidays in August, the move was rejected,” explained the Minister of Health Marek Krajči on the day the government decided to go ahead with the nationwide testing programme and partial lockdown.

The PC continued to meet in the summer months too. In June 2020 it stepped up its activities and has since met eight times (during previous years, it usually held a maximum of two meetings a year).

Reacting to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the PC developed new statutes, which defined its role and powers during a crisis. The statues were then adopted by the government. In years before the pandemic, nobody cared to do so.

In the summer after the first wave, the PC prepared and adopted a new plan to fight COVID-19, which focused on five phases of the pandemic and roles of different government institutions and departments. It also introduced a centralised notification system for hospitals and state administration.

In line with these plans, in September, when it became clear that the second wave was gathering momentum, the PC imposed restrictions on mass gatherings, including weddings. The Minister of Health Marek Krajci announced the decision on September 11. The restrictions were scheduled to come into effect on October 1.

But the plan was soon abandoned because the epidemic situation in Slovakia did not seem quite as dramatic at that time (among 4,200 people tested, 186 or 4.4 per cent tested positive). This came to the attention of the country’s PM, who got involved after he learned that there was a petition against the new restrictions signed by over 24,000 people.

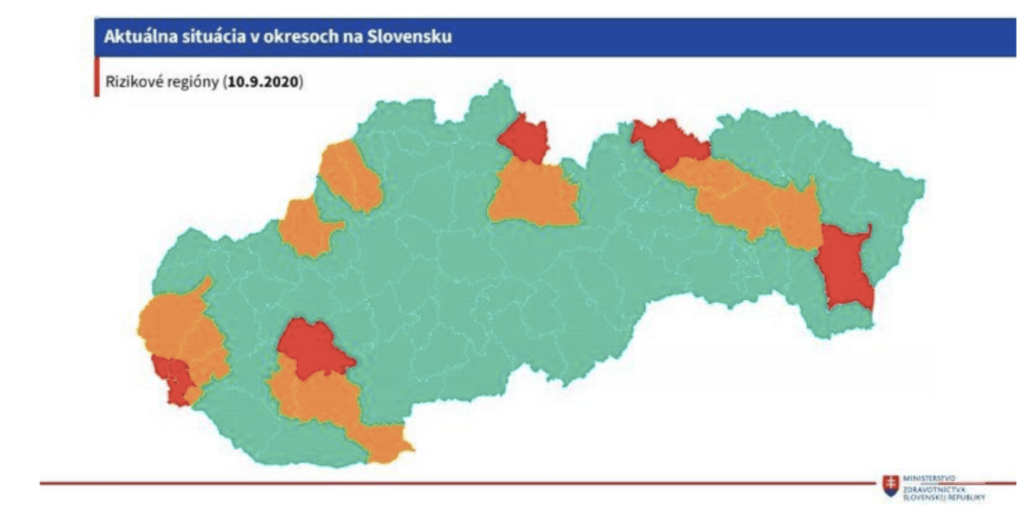

Source: https://www.health.gov.sk/

There is little doubt that wedding receptions became a sensitive topic for the country’s PM, as not long before that, he had attended a large wedding reception of a fellow MP. Photos show that neither he nor other politicians cared to wear face masks, which were mandatory at that time. Both experts and the opposition criticised the Prime Minister’s carelessness.

Slovakia’s PM Igor Matovič at a wedding reception of a fellow MP with no face covering. Source: Facebook/U HRICKA Restaurant

Hours after his “EVERYTHING’S GONNA BE ALL RIGHT” Facebook status, the government decided to allow wedding receptions to be organised for up to 100 people providing they wear face coverings. The government thus overruled the decision of the PC. The PM disregarded the advice of experts and chose to make a decision that would help increase his popularity.

It contrasted with decisions taken by the government during the first wave of the pandemic, which seemed to be largely based on expert advice.

By October 2, the number of “red zone” municipalities increased to 41. Seven days later, it reached 62, with the country’s northern region of Orava, which borders Poland, suffering the worst outbreak in Slovakia. Experts and the police blamed the alarming infection rate on public gatherings, including large-scale wedding receptions. Before the summer, the region had seen few cases of COVID-19.

In contrast to the PC, the Slovak authorities were not busy in the summer getting the country ready for the second wave.

The government went into a summer recess, meeting only five times in July (COVID-19 was discussed at only three of the meetings) and three times in August (the pandemic was discussed only once). During the first wave of the pandemic, the government would usually meet at least ten times a month.

No substantial orders related to the pandemic (personal protective equipment, ventilators) were placed in the summer. The last large procurement of ventilators was concluded in April when the Ministry of Health bought 300 units from Chirana Medical, a local company.

The ministry’s spokeswoman Zuzana Eliášová claimed that the government “reacted in advance and secured a sufficient number of [ventilators] for Slovakia”. Besides the 300 units acquired from Chirana, the ministry also bought 88 more from three other suppliers.

Chirana CFO Oskar Baranovič confirmed to ICJK that before the end of June, the company had delivered all 300 ventilators for the Ministry of Health. “Due to a rapid spread of COVID-19 cases in Slovakia during Q2, a number of devices from the last production batch were stored in a specialised warehouse maintained by the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic.” Baranovič also said that the ventilators were only transferred to hospitals in October.

The Ministry of Health is not the only entity that procures ventilators in Slovakia, they can also be acquired by hospitals. Chirana claims they have sold 80 additional units to Slovak hospitals. Some of the country’s hospitals have also acquired them from third producers.

According to the ministry’s spokeswoman Eliášová, there are currently about 900 ventilators that can be used to treat COVID-19 patients, double the number available in spring, but short of the “at least 1,000 ventilators” promised by the Minister of Health early this year.

As regards other pandemic-related purchases, by the end of October, the State Material Reserve Agency (MRA) has spent a total of over 72 million euros. They include, among others, personal protective equipment and tests. Over 52 million euros were spent recently just to buy the antigen testing kits needed for the blanket testing programme.

Most of the remaining 20 million euros were spent during the spring shopping spree when the prices for the personal protective equipment skyrocketed after the COVID-19 outbreak dramatically increased global demand. A public record of purchases available on the MRA website reveals that in July and August only one purchase was made with the pandemic in mind. The MRA bought cleaning and hygiene products for 383.16 euro.

In June, the administration of the MRA opened a public procurement procedure for personal protective equipment in a plan to buy over 30 million euros’ worth of personal protective equipment. The procedure has not yet been concluded.

During the summer, when the pace of the pandemic slowed down and prices were still relatively low, Slovakia failed to take advantage to stock up on the necessary equipment. We will soon learn the hard way whether that was an error of judgment and Slovakia, again, be forced to buy overpriced gloves and masks.

Other institutions also seemed to be relishing the summer mood instead of preparing for the likely second wave. Unfortunately, they included the PM’s main advisory body, which had regularly convened during the first wave.

Even though such specialists hold no formal powers, the government often presents their decisions as its own or hides its political decisions behind the authority of experts. Once again, it is unfortunate that during the pandemic expert advice was far from being in large demand.

The Ministry of Health claims the PM’s advisory body held meetings “in response to the current development of the pandemic”. During the summer, it held five meetings in July and August. After the second wave hit Slovakia, the experts began to meet more frequently, up to five times a month.

The Permanent Crisis Staff (PCS) is another entity that focuses on combating the coronavirus pandemic in Slovakia. Dr Peter Visolajsky, who is also the chair of Medical Trade Unions, attended all meetings during the first wave. Now, he remains critical of the government activities and particularly of the way it failed to prepare for the second wave of the pandemic.

He believes that the government failed in three areas: “Although in neighbouring countries the healthcare system is not in good shape either, their healthcare workers do feel that the country needs them and the government recognises that,” he told ICJK.

He referred to the fact that medical workers in those countries had already received a raise, while Slovakia failed to deliver and hadn’t even paid bonuses promised during the first wave. To make things worse, the Ministry of Health increased penalties for medical errors.

Visolajský argues that hospitals were unprepared by the state central authorities for the second wave because until recently, there had been no national contingency plan for transferring patients with Covid-19 in case hospitals become overwhelmed. Also, some hospitals that were supplied with ventilators have restricted access to oxygen.

The ultimate failure of the government includes regional offices of the Public Health Authority (PHA). People who work there are responsible for the diagnostics, contact tracing of the infected and their early isolation.

Tracing the collapse or the collapse of tracing

“When the representatives of regional PHA offices announced during the summer that they would be able to handle 50 cases daily, it was immediately clear that the system would break down if the number of cases doubled,” Visolajský explains.

He also pointed out that PHA’s ability to handle more cases has not increased. “It is unfortunate that there have been voices that the PHA budget will be discussed no sooner than the following year. If we are having a problem right now, increased funding scheduled for next year is not going to help us today. The fact that regional PHA offices cannot handle more cases is already negatively affecting us,” he argued.

The PHA disagrees, claiming that regional offices from the hardest-hit regions are now being supported by workers from the country’s regional offices. They also claim the Ministry of Health provided them with additional funding to contract temporary workers as contact tracers. Also, the number of soldiers who are helping in the effort increased. PHA spokeswoman Daša Račková has said that the extra sources increased the number of people working on tracing COVID-19 contacts from 314 in September (including 9 soldiers) to 955 on November 1 (including 144 soldiers). Not all of them are new employees, some had previously worked in other capacities at the PHA. The Agency, however, failed to provide a breakdown of those numbers.

Another possibility to increase the country’s contact tracing capacity includes amending the law on healthcare providers. As a result, the PHA turned to medical students to the work as contact tracers. However, based on the numbers that Račková provided, only 64 medical students are helping in the effort.

The PHA also provided us with data for the period between September 1 and November 1 (but not for the summer months). We do not know whether these decisions, including the decision to send 144 soldiers to work as contact tracers, were implemented in September, October or in recent days only. The context is important because when the second wave hit some Slovak regions in late September and early October, the country’s testing capacities seemed to have collapsed.

But it does not just boil down to funding and staffing shortages. During the first wave, the parliament passed a new law put forward by the government, which gave state agencies access to the localisation data of the citizens’ mobile phones.

These were used in an app called “E-quarantine”, an alternative to being placed in a state-run quarantine centre after arriving in Slovakia from abroad. The app tracks the location of the individual’s cell phone and checks if the owner stays at home for the duration of the mandatory quarantine. Data sent by mobile devices were meant to help trace contacts of people who tested positive to minimise the spread of the coronavirus.

Source: https://korona.gov.sk/

As this law raised personal privacy concerns, the government coalition had to reject the veto of the country’s President Zuzana Čaputová and an appeal lodged with the country’s Constitutional Court. The government and the coalition eventually succeeded in doing so.

Despite enormous effort placed into adopting this law, when the second wave of the pandemic hit in the autumn, Slovakia’s state agencies seem no longer interested in using localisation data.

That decision was confirmed by Richard Sulík, the Minister of Economy and chairman of the coalition party Freedom and Solidarity (SaS). In an interview for Radio Expres on October 13, he said that the authorities no longer use mobile data to track those quarantined at home or to trace people infected with COVID-19.

ICJK’s source who works at one of the regional PHA offices, which is responsible for contact tracing and calling people who have had contact with people who tested positive, confirmed that Slovak tracers never used localisation data and the only available method involves calling residents who tested positive and asking them if they remember their contacts.

Those painstakingly difficult and slow tasks soon overwhelmed PHA employees, despite the Agency’s spokeswoman confirming that new staff have been hired.

Our sources from Orava, a region that reported the country’s largest number of infections, claim this led to a partial collapse of tracing and testing. Under normal circumstances, every person confirmed to have come in contact with someone who tested positive is referred to take a PCR swab test even if they show no apparent symptoms.

This is no longer the case in some regions, as tracers are unable to call all possible contacts and even if they do, testing sites are quickly overwhelmed. The Námestovo County in the northern region of Orava has no testing site and its residents need to travel to neighbouring counties.

As regards smart pandemic solutions, Slovakia still has no mobile app that would check if a person has been near other users who have tested positive, similar an app developed in the neighbouring Czech Republic called “e-rouška”.

At the onset of the pandemic, a group of Slovak volunteers developed an app but the government ignored pledges to embrace it as official and claimed it was going to work on a better solution, one that would incorporate mobile data that the state has access to as a result of new legislation. That was the last time we heard about any contact tracing app.

Deus ex machina

“People longed for freedom, deluded themselves that the virus has disappeared for good. For three months, they had been attacked by conspiracy theories and nonsense that spread on social media. All of this has taken its toll. We enjoyed a brief moment of freedom, we enjoyed it for a while, and now, unfortunately, we have to face the consequences,” PM Igor Matovič said when he announced a nationwide testing programme on October 21.

The idea for a nationwide testing programme had come to the Prime Minister, as he later admitted, a few days earlier. He was trying to react to criticism that had befallen his government, accusing him that they wasted away summer months instead of focusing on trying to contain the spread of the virus. The idea for blanket testing came as he tried to avoid full lockdown that would wreck the economy.

The plan to test the whole population using less accurate rapid antigen tests instead of PCR tests, which are slower and more expensive, was coupled with partial lockdown, which would not apply to people who are travelling to take the test or those who have already tested negative.

But immediately after the plan was announced, the plan to mass test Slovakia’s entire population became a source of controversy, as the government failed to inform the country’s president, who learned about the plan from the government’s press conference. The Slovak president is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and it became clear that the army was to play a crucial role during the nationwide testing programme.

The government also failed to inform and consult local governments in the country’s regions and municipalities, which would need to take on a sizable burden of the planned operations.

The testing also required hiring tens of thousands of healthcare workers to work at the weekend. As a result, Slovakia’s Medical Chamber and the Association of Towns and Communities both considered the plan unrealistic.

Less than 24 hours before the nation-wide testing began, the president announced that as a result of a shortage of healthcare workers only about 60 percent of testing points were ready.

Still, on the morning of October 31, over 98 percent of testing points opened, as many healthcare workers decided to help at the last minute. Slovakia nationwide programme was also supported by army medics from Austria and Hungary, part of a humanitarian mission.

Wyświetl ten post na Instagramie.

After the weekend, the government declared “victory”, often drawing comparisons to D-Day in Normandy or the Slovak National Uprising against Nazis Germany and the puppet government of Jozef Tiso.

Was it worth it? Did the Government find the ultimate solution to COVID-19 even though it had failed to prepare the country to contain the second wave? Data from Orava region seems promising as after the first weekend of testing the number of new cases has decreased. We need to wait, however, until more comprehensive data are available. Countrywide, however, in the first few days after the massive effort, the infection rate does not seem to be slowing down – even PM Igor Matovič and Minister of Defence Jaroslav Naď had to quarantine themselves after they had a contact with people who tested positive.

As regards Orava, it remains questionable whether it was the massive testing that broke the curve – or whether it should rather be attributed to strict lockdown imposed before and after the testing, much stricter than the rest of the country experienced.

The antigen testing, while much faster and cheaper, is also much less accurate than the standard PCR test. And that means there are now probably tens of thousands of false-negative people who have been issued a “negative” certificate and are now taking advantage of the freedom of movement, possibly spreading the disease further.

While the government might just be buying some valuable time, it does not seem that it has learned its lesson. The country’s ability to trace contacts remains low as institutions are understaffed and efficient data processing needs to be addressed too.

Although the immense logistics stunt by the government was possible as a result of support from the army, healthcare workers, volunteers and municipalities, it failed to gather data about negative and positive tests in a meaningful way.

The second round of mass testing is only being carried out in municipalities where the infection rate during the first round exceeded 0.7 – that means 45 counties. The remaining tests will be used at the country’s borders.

Having investigated the actions undertaken by the country’s authorities, it becomes clear that many of the measures adopted after the mass testing programme had already been suggested by experts weeks before the government decided to test the whole population. After all, the PM’s decision to ignore expert advice and play into the hands of the public to allow large weddings largely backfired. This is particularly alarming as it is also becoming clear that the coronavirus in Slovakia can only be contained through rigorous anti-epidemic measures.

Cover photo: A healthcare worker collects a swab sample from a person at a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) testing site during a second round of mass nationwide testing, in Trencianske Stankovce, Slovakia November 7, 2020 Photo by RADOVAN STOKLASA / Reuters / Forum

Lukáš Diko is the editor-in-chief at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK). An experienced journalist and media leader, he was previously director of news and journalism at RTVS and editor-in-chief of news at Markíza television.