Illustration: Mart Nigola (Delfi Estonia) 2024-06-04

Illustration: Mart Nigola (Delfi Estonia) 2024-06-04

Less than a month before Russia’s “presidential elections,” the Kremlin commissioned a secret sociological survey – the results of which VSquare has in its possession. The survey reveals how voters actually felt about the presidential “candidates,” and where the country’s center of actual opposition lies.

If the presidential elections were held this Sunday, which candidate would you most likely vote for? How credible do you think the results of the upcoming presidential elections are? Do you support or oppose the decision to launch a special Russian military operation in Ukraine? Do you think the military operation is proceeding successfully? How proud are you of the current situation in your country?

These are just a few of the questions from a major poll of more than 44,000 respondents conducted between the 19th and 26th of February of this year by ANO Dialog Regions, a nonprofit that is autonomous in name but Kremlin-funded and controlled in reality. The results were presented to the Putin administration’s domestic policy bloc, headed by Putin’s close comrade-in-arms, Sergei Kiriyenko.

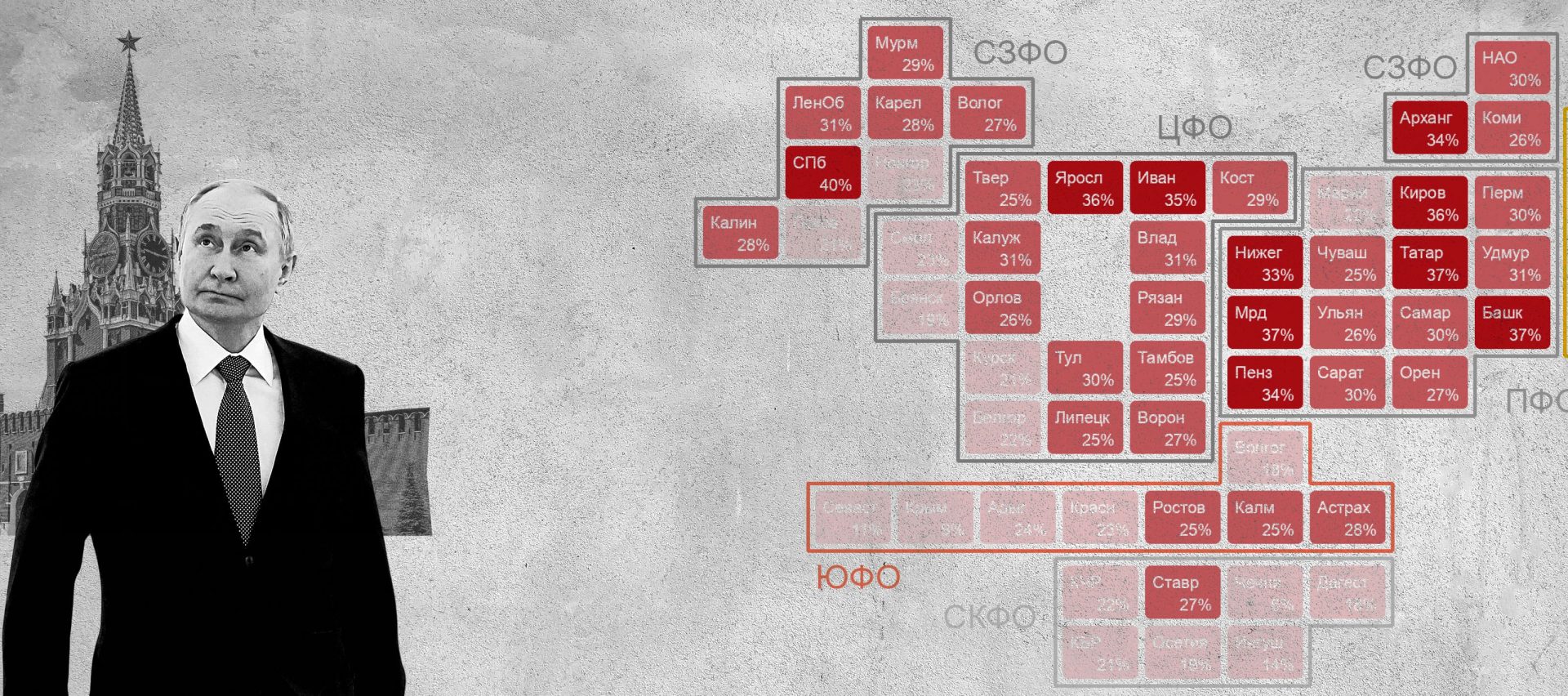

Do you approve or disapprove of the Russian President’s performance overall? The percentage of “approve” answers by region.

The 116-slide presentation of this poll, as well as other Dialog Regions documents, are now in the possession of VSquare and our research partners. This is the next chapter in our Kremlin Leaks series—a chapter that reveals in detail the real attitude of Russian society toward the country’s leadership and the war against Ukraine, and shows how the Kremlin, sometimes in absurd fashion, orchestrated Putin’s personal election campaign.

Do you approve or disapprove of the Russian President’s performance overall? The percentage of “disapprove” answers by region.

The results of the survey clearly show opposition in Putin’s home city of St. Petersburg. The survey also reveals that the delay in the US aid package to Ukraine contributed to the Russian belief that the “special operation” will be a success, and why Putin fears the next wave of public mobilization.

Kremlin Leaks is a series of articles based on leaked documents from the Russian presidential administration. In previous articles in the series, we revealed how the Kremlin is waging an information war against its own society and poured hundreds of millions of euros into Putin’s reelection. We also revealed that the Kremlin made the Russian Red Cross part of its war and propaganda network. As a result, the International Red Cross launched a separate investigation.

Our partners in this series of articles are the newspaper Expressen from Sweden, the Russian independent publication Meduza, the Central European and Polish investigative publications Vsquare.org and Frontstory.pl, Lithuanian Public Broadcaster LRT and German investigative journalism outlet Paper Trail Media.

Two days before the start of the polling period, Ukraine withdrew its troops from the town of Avdiivka in the Donetsk region. The capture of Avdiivka was Russia’s biggest military success since Bahmut. The day before, opposition leader Alexei Navalny died in a Siberian prison camp. Opposition politician Boris Nadezhdin, who proved unexpectedly popular, was barred by the Russian electoral commission from running for president on February 8. Less than three weeks remained until the “elections.”

It was in this context that Dialog Regions carried out a nationwide poll with 44,100 respondents. Respondents were found via what is known as river sampling: people were invited to participate in the poll while on Russian social media channels VKontakte and Odnoklassniki, and the sample was matched with actual socio-demographic data from the country.

However, according to some of the experts we consulted, it is also risky to rely on any opinion poll because in recent years, it has been difficult to carry out sociological surveys in Russia that reflect reality – how can people reply to polls honestly when they know that any kind of dissent against the Putin’s regime will be punished. We were not able to analyze the underlying data of the poll to verify its accuracy.

Dr Nerijus Maliukevičius, a propaganda expert at Vilnius University’s Institute of International Relations and Political Science, said that the main indicator of the credibility of surveys is the transparency of the methods and in this case it is not possible to say if or how much the results were fabricated. “But the way this was presented to the employer seems serious enough,” he said.

The only region not shown in the survey results is Moscow. Presumably, this was because Dialog does not have permission from the Kremlin to monitor Moscow. According to experts consulted by VSquare and partners, Moscow’s results could have been comparable to those gathered in St. Petersburg or even more critical of Russian leadership.

We presented the results of the study to Tarmo Jüristo, the head of Estonian pollster SALK, Rainer Saks, a security expert and former director general of the Foreign Intelligence Agency, and Igor Gretski, a research fellow at the think-tank International Centre for Defence and Security (ICDS).

According to Saks, the survey was professionally put together. At the Kremlin’s behest, Saks said, it would have been used to find out what the Russian people were thinking about what was going on in the country at that particular moment. Our documents also show that a similar poll is conducted every month.

According to Saks, the Kremlin conducts such secret surveys purely for the president, not for the country. “These results are presented to the president and, if necessary, specific guidelines are passed on to the government: shto dyelat,” Saks said. What is to be done.

According to Jüristo, the river sampling method is technically not a random sample. However, if the platforms from which respondents are sought are chosen successfully, a balanced set of respondents can be obtained.

“The downside is that respondents are less focused and the drop-out rate is likely to be higher. On the plus side, however, they are less ‘odd’ compared to the societal baseline. This could result in a more representative sample than in a custom online panel,” explained Jüristo.

Three weeks before the election, 59% of respondents said they would vote for Putin. Vladislav Davankov, who was the closest resemblance of an opposition candidate after Boris Nadezhdin was knocked off the track, had a 6% rating. Although the official result on election day showed Putin with a record 88% of votes, it is not worth getting too excited about such a big difference, as respondents also had the option of saying they would spoil the ballot, not go to the polls or refuse to state a preference. A number of other polls conducted before the election, the results of which were made public, showed similar levels of support for Putin.

If those respondents who did not declare a preference, pledged to tamper the ballot or not vote were removed from the 100%, Jüristo calculates that Putin would have won by 79.7% — a sure win, but still not 88%.

Secondly, Jüristo pointed out that according to the poll, 77% of the population planned to participate in the elections, a level that was identical to the officially declared turnout. “This is very doubtful, because in polls people always overestimate their intention to vote,” he explained. This, he said, confirms that the election result was heavily manipulated, but with relatively little impact on the outcome.

“Even if nearly half of Putin’s votes were added to the boxes or the ballot papers, this would raise his final result by a total of 8-9 percentage points. In other words, Putin would have won by a huge margin even if the votes had been counted fairly,” he said.

More significantly, however, 23 % of respondents, or virtually one in four people, said they would not vote for Putin under any circumstances. From the Kremlin’s point of view, the situation in St. Petersburg was the most critical. This is Putin’s birthplace and the place where his political career took off in the 1990s — and is developing into a site of anti-Putin discontent.

There, 47% of respondents, which is to say less than half of those eligible to vote, said they would vote for Putin. However, 38% said they refused to vote for him. Fifteen percent of respondents promised to go to the polls, but only to tamper the ballot paper. This figure was also overwhelmingly higher in St. Petersburg and the surrounding Leningrad Oblast than in the rest of the country. (Going to the polls to spoil the ballot was one of the appeals of Russia’s fragmented opposition to voters.)

Which brings us back to St. Petersburg. While the national average approval of Putin’s actions is 64% and disapproval is 20% (the remaining 16% refused to answer), in St. Petersburg, the figures are 54% and 37%, respectively.

Igor Gretsky, a researcher at the ICDS, called St. Petersburg, which has a population of more than five million, the protest capital of Russia. Its size means it could become a significant problem for the Kremlin.

“The Kremlin is very likely to tackle this problem in the next few years [of Putin’s term]. They are trying to dilute the opposition there by bringing in people from the so-called new territories (the occupied territories of Ukraine ) and the North Caucasus. They are probably trying to deal more with the local issues and problems on the ground,” Gretsky said.

At the same time, he said, those who do not support the war in Ukraine are gradually being ejected even from opposition circles. “I am sure that by the time of the next presidential elections, the numbers in St. Petersburg will be very different, because a new generation will come to the polls, coming from an already ideologised education system.”

A separate block of questions concerned how legitimate the Russian people consider the presidential elections and their results to be. According to the results, only two out of every five people believed that the official results were “in line with the actual vote.” One in five thought that there was some fraud but that this did not affect the overall vote, and 28% said the results were not in line with reality.

Do you think the election results will be credible or not? Answers: credible.

When asked to name up to three reasons why they thought the elections were unfair, people cited the mass stuffing of ballot boxes with pre-printed ballot papers and the pressuring of government officials, law enforcement and other agency staff to vote as the main reasons.

“The low credibility of elections could be a problem for a democratic society, but in the Russian mind it is not,” said Gretsky, who added that Russian society operates in a much more cynical way. People are interested in a decent life, a stable income. Everything else is secondary.

Do you think the election results will be credible or not? Answers: not credible.

“The opposition, seeing these results, may want to spread the message that Putin’s rule is not legitimate, that the election results are rigged and want to consolidate people around this issue. But this will not happen because this issue is simply not important for a very large majority in society,” Gretski said.

At the same time, it appears that the problem of low legitimacy was something the Kremlin saw it had to address. Thus, mass campaigns were organized before the elections to raise people’s confidence in election integrity.

If the question of “Putin’s election” was never whether he would be elected or whether the election would be rigged, but how much popular support for Putin the Kremlin would formally claim Putin received and how the election would be rigged, then answers to questions about support for the so-called special military operation perhaps carry longer-term weight.

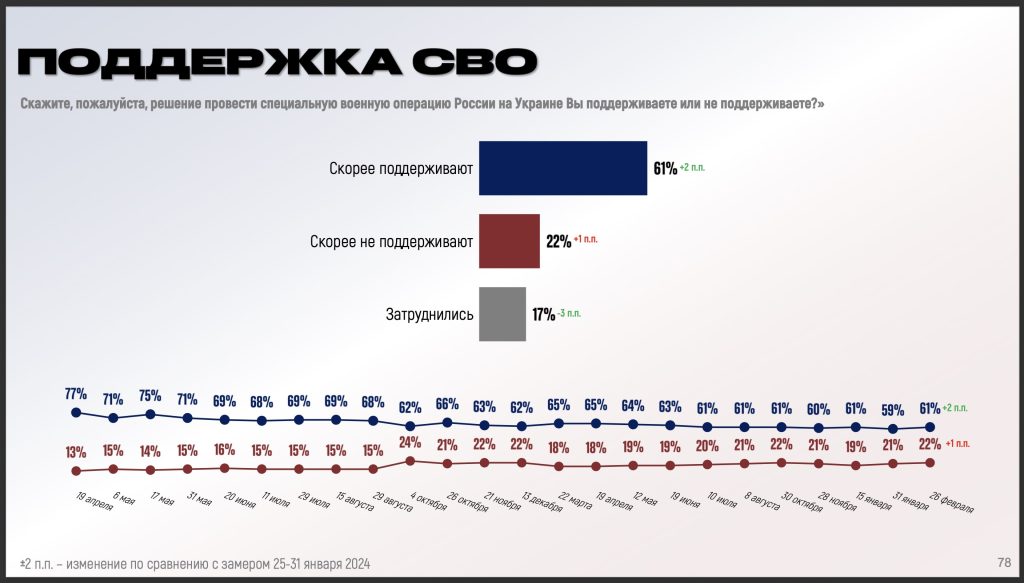

Firstly, people were asked whether or not they support ”the decision to carry out a Russian special military operation in Ukraine.” Over the past six months, these numbers have remained essentially static: 61% of respondents supported a bloody war against Ukraine in the last poll, while 22% opposed. The remaining 17% did not want to answer.

Dialog Regions, however, has been “polling” on the same question essentially since the first days of the invasion of Ukraine. A long line of data shows that in April 2022, support for the war in Russian society stood at 77%, with only 13% against. A significant change, however, took place in September 2022, which was precisely when the recently ousted Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu publicly declared mobilization and the Russian front in Kharkiv collapsed. As a result, support for the ‘special operation’ plummeted by six percentage points in one month, down to 62 percent; the number of those opposed jumped from 15 to 24%.

“This shows that the price of the second mobilization wave is exceptionally high [for the Kremlin]. They will do everything they can to avoid it,” Gretsky said. If the next mobilization wave were to bring a reaction of the same magnitude, the levels of support and opposition would be uncomfortably close for the Kremlin.

“It is for this reason that it is crucial that the West continues to support the Ukrainian armed forces, so that by the beginning of next year, Ukraine will have achieved tactical success. People will only be prepared to support a “special military operation” as long as politics knocks on their door,” he added.

Secondly, people were asked whether they think the “special military operation” is proceeding successfully or unsuccessfully. Compared to a month earlier, in January, the number of people who thought the war would be a success rose by seven percentage points to 53%. (One in five people thought the special operation would not be a success, and a further 27% did not want to answer.)

VSquare consulted a number of experts and war analysts who pointed to two factors as the reasons for this increase. Firstly, Russia captured the town of Avdiivka in Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast in February. This was the Russians’ most notable achievement since the capture of Bakhmut in May 2023. Secondly, and unambiguously linked to the reason that the Ukrainians retreated from Avdiivka, the Ukrainian army was plagued by a growing shortage of ammunition and weaponry. The US aid package was hopelessly bogged down in the House of Representatives, and Russian propaganda media were beating the drum on the issue.

According to Rainer Saks, the marked increase in support for the “special operation” shows the importance of the West’s continued aid to Ukraine, not least because of its direct impact on Russian society. On the other hand, if the number of coffins arriving on the doorstep does not fall, this will drag down support for the war. “It’s hard to measure, but nowhere near the border are the Russian people prepared to fight this war any longer. The Kremlin’s biggest fear is if their narrative of the war’s success collapses,” he said, but added that it is very difficult to convey such knowledge to the Western leaders.

Russians are also increasingly proud of their country. As recently as January, 42% of people said they were proud of Russia’s “current situation” compared to 36% who said they were not proud. A month later, however, the gap had widened, with 46% feeling proud and 34% not proud. However, in many regions, a majority of people are not proud of their country. In addition to St. Petersburg, this is also the case in the oblasts of Kirov, Yaroslavl, Ivanovsky, Tomsk and Mordovia.

Despite all this, Igor Gretsky said that the Kremlin would have been pleased with the results. After all, a large part of society continues to support and trust Putin and the war against Ukraine. This is particularly striking in the regions of the North Caucasus. The Kremlin also sees the situation as being fully under control in the militarily important Pskov Oblast and in all oblasts bordering Ukraine, despite Ukrainian efforts to show that the war is reaching and impacting Russia’s own backyard, and even Russia itself.

Putin is buying society’s loyalty with money, a development Gretsky described as a kind of new — and cynical — social contract. “The allowances for soldiers’ families are working, and this is also why we don’t see the kind of movements of soldiers’ committees we saw in the 1990s. They asked the key question: what did our children die for? Putin is now giving a clear answer to that question. The government is paying for [society’s] total loyalty,” says Gretsky.

And the Kremlin is confident. As long as the money keeps flowing, they will control the situation in the country. There will be plenty of out-of-state buyers for Russia’s natural resources. “For the foreseeable future, Russia will have enough money to keep the country under control, to maintain a decent standard of living for the people, to meet the demands of the siloviki and to pay for the needs of the defense ministry,” Gretski said.

Head of the investigative desk at Delfi Estonia, Holger Roonemaa has extensively investigated topics related to national security, including Russia’s espionage, interference, and influence operations in Estonia and the wider region. He is a member of the International Consortium on Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Estonia’s national media association named him the journalist of the year in 2020 and 2021.