Shortly before the early parliamentary elections last September, Slovakia expelled another Russian diplomat. This was the thirty-ninth Russian diplomat expelled from Slovakia since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As the election campaign was in full swing, the news did not garner much of a reaction. The Foreign Ministry issued a press release, and Moscow reacted immediately.

But according to our findings, it was an inconspicuous employee of the Russian embassy’s trade mission in Bratislava who became the persona non grata. The thirty-something year old man was involved in influence operations and wanted specifically to try to impact the elections through his network of contacts. The findings of the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK) suggest that he may have been a member of the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service.

Slovakia has expelled almost 50 Russian spies in the last twenty years. Most of them were kicked out after 2020. Between 2004 and 2018, for example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not expel a single Russian agent, despite the fact that the Slovak government had information about their activities. Russian intelligence activities intensified in Slovakia after the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Slovakia did not even expel any diplomats after the poisoning of former Russian agent Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom in the spring of 2018. While other NATO allies expelled several suspected intelligence officers, such efforts in Slovakia were reportedly blocked by Andrej Danko, then chairman of the pro-Russian, nationalist SNS party, which was part of the coalition at the time. It was only in November 2018 that a diplomat was finally sent back to Russia for espionage. The big waves of expulsions for breaches of the convention on diplomatic relations, i.e. de facto for espionage, did not come until 2020, and were mainly a result of the Vrbětice case. Further exclusions came after, and were the result of, the start of Russia’s all-out war in Ukraine.

The expulsion of the Russian diplomat before the elections in September 2023 did not attract as much attention as those after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In fact, it was only a month later that Foreign Minister Miroslav Wlachovský told Denník N that the expelled diplomat was a Russian spy with diplomatic cover who had been trying to influence the Slovak elections. “This diplomat, or person with diplomatic cover, had a well-developed network of collaborators here and tried to influence public opinion and the situation before the elections,” the minister said in an interview.

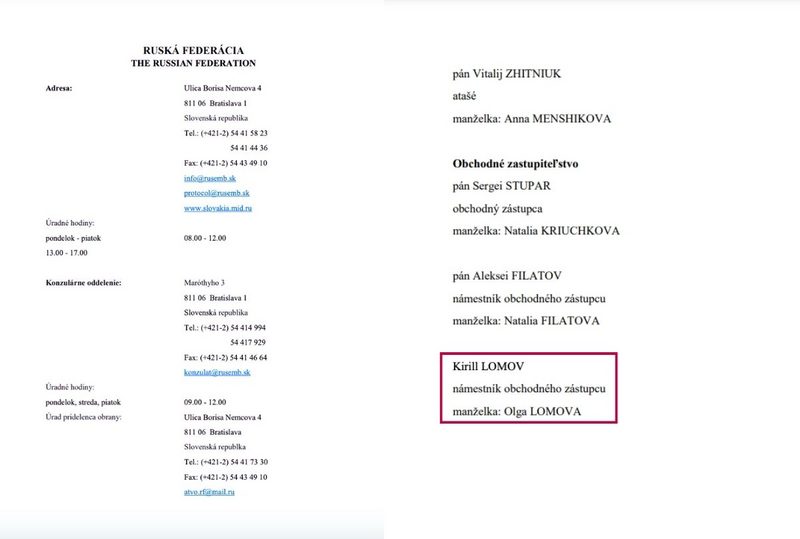

The ICJK has now managed to identify the expelled diplomat. He was an economic diplomat by the name of Kirill Lomov, an employee of the Russian Embassy’s Trade Mission in Bratislava. He had to leave Slovakia within 48 hours. According to ICJK sources, this is an extremely short time, and that he was only given two days is related to the seriousness of his activities, which were in violation of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

According to a source with close knowledge of Slovak diplomacy, Lomov was probably an associate of the Russian SVR external intelligence service. His proximity to the SVR is also suggested by findings from the London-based Dossier Center, which cooperated with ICJK on this investigation. In fact, the list of Lomov’s residential addresses includes the address of an SVR housing facility in Moscow. It was the SVR chief Sergei Naryshkin who spoke about the manipulation of the elections in Slovakia at the very time when, literally hours before the polls opened, a deep fake footage of an alleged conversation between journalist Monika Tódová and the liberal Progressive Slovakia party’s leader, Michal Šimečka, began to circulate on social networks. The head of the Russian intelligence service accused the United States of interference in Slovakia’s election.

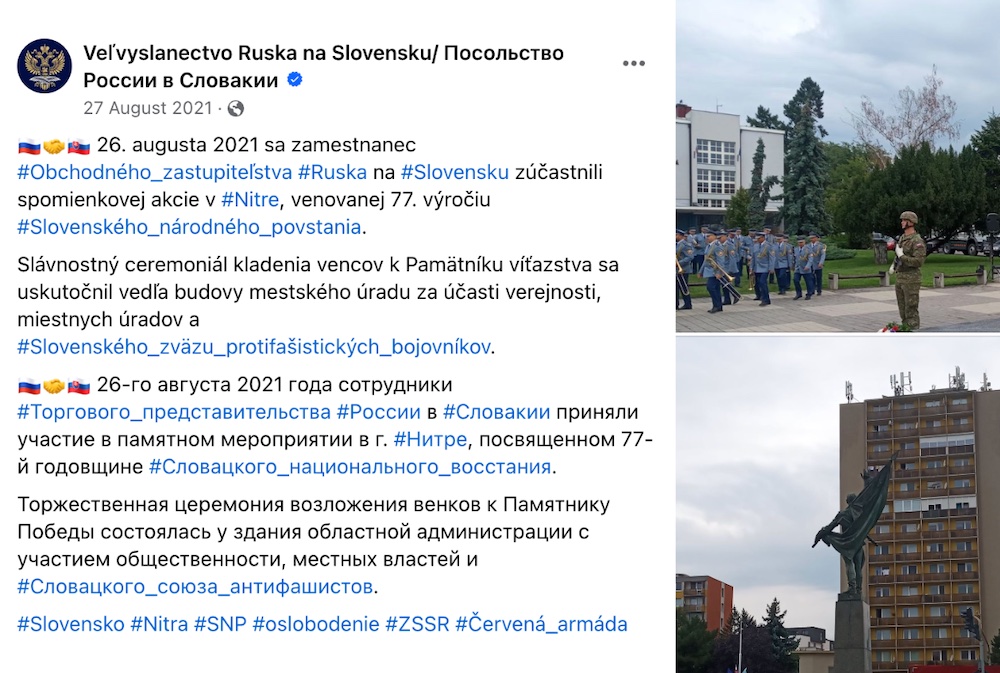

The inconspicuous Lomov at the commemoration of the 77th anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising in Nitra. Source: Facebook

To influence and polarize

The expelled economic diplomat, Kirill Lomov, was involved in media and influence operations in Slovakia, where he had a large network of associates, according to ICJK sources. The country’s civilian national security agency, the Slovak Information Service (SIS) has repeatedly warned in annual reports that Russian intelligence services are active in Slovakia for a range of reasons, including “to influence public opinion in favor of the Russian Federation.”

According to the Military Intelligence Service, which recently uncovered a Russian espionage network, Russia’s aim is to undermine trust in the state and state institutions, and to do so by using, and worsening, society’s polarization.

For decades, such operations fell under the domain of Soviet, and later Russian, intelligence services. Libor Kutěj, former deputy director of the Czech Military Intelligence and director of the Institute of Intelligence Studies at the Brno University of Defence, thinks that behind these activities is “an effort to change the social mood of the public in the target countries, to induce distrust in their constitutional institutions … to relativize the values of society, to reduce the credit of the institutions of the democratic state, and thus to declassify the principles of democratic society as a whole.”

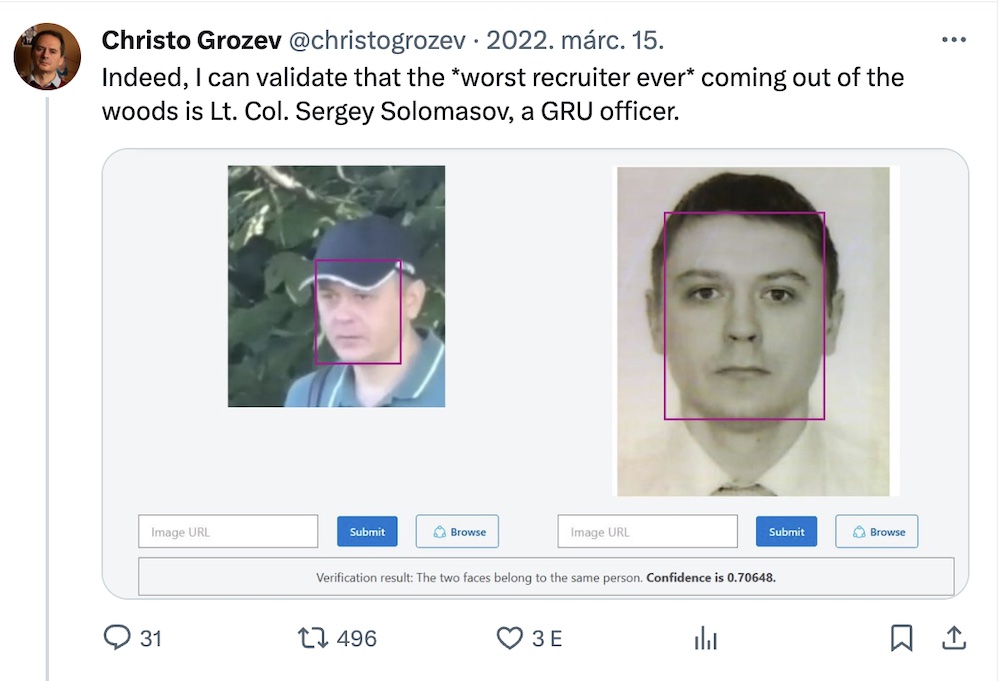

According to the Slovak intelligence services, members of two Russian services—the External Intelligence Service (SVR) and the military Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU)—are operating on Slovak territory. However, according to Kutej, it is difficult to say which of them carries out the greater number of operations, or to specify the nature or aim of the operations. “Given the current security reality in Eastern Europe, the GRU military intelligence service is very active,” Kutěj says.

“The GRU has a high professional credit, although some of the excesses revealed suggest that quantity often outweighs quality,” the former intelligence officer recalls. It is, however, a service that is known for its harsh methods. “In Slovakia, one can expect a similar course of activities as in the Czech Republic,” the expert warns.

Sergei Solomasov, a former military attaché at the Russian embassy in Bratislava, was also a member of the GRU. Under diplomatic cover, he had also recruited Bohuš Garbár, a contributor to Hlavné správy, a disinformation portal (in 2022, a video of the money handover involved in his recruitment was published and went viral). For this, Garbár has already received a three-year suspended sentence for the crimes of accepting bribes, and espionage.

Zdroj: Twitter

The expelled Kirill Lomov appeared on Slovakia’s list of foreign diplomats in May 2022. However, the results of a facial recognition search indicate that he has been in Slovakia since at least August 2021.

We have contacted both the Slovak intelligence services and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which decides on the expulsion of diplomats, with questions about his activities.

The Slovak Information Service (SIS) said that information about specific cases is legally protected classified information and therefore cannot be published or made available. Both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Defence (under which Military Intelligence falls) responded similarly.

In comparison to Slovakia, in the Czech Republic, the intelligence services reveal more to the public. They give more details in their annual reports, and the head of Czech counter-intelligence has spoken publicly about Russian influence practices. In fact, the Czech Security and Information Service (BIS) publicly exposed a Russian agent who, for a bribe of several thousand euros, arranged for the dissemination of Russian propaganda about the war in Ukraine.

We also asked the Russian Embassy in Bratislava for a statement, but its representatives did not respond to our questions.

Close to the Russian secret services

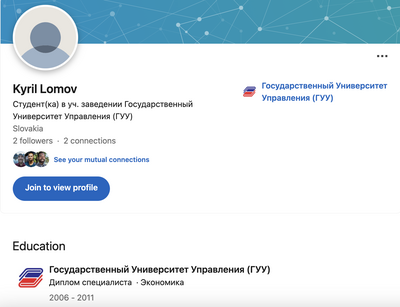

According to the Dossier Center’s findings, the expelled spy, Kirill Vladimirovich Lomov, was born in 1990 in the city of Astrakhan in southern Russia, in the delta of the Volga River. His date of birth is the same as that of his brother, Maxim. Their career paths were also similar: both worked in Russian Rosinter chain restaurants. Maksim eventually joined the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while Kirill worked in the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

According to a brief professional biography on LinkedIn, Kirill studied economics at the State University of Management in Moscow. His education probably fated him to become an economic diplomat, and he did: around 2022, he became Deputy Commercial Counsellor at the Russian Embassy in Bratislava.

Source: LinkedIn

Kirill Lomov appears to be close to other Russian intelligence services as well. Among his previous addresses was Moscow’s Bolshaya Lubyanka 1, which is known as the accommodation facility of the FSB, the Federal Security Service. However, the address is most likely his father’s, not his—according to one of the documents Dossier uncovered, Lomov’s father either worked or works for the FSB.

Lomov seems to have guarded his privacy well. Only one diplomatic document and the public results from a series of Bratislava-based competitive running events , shed light on his presence in Slovakia. Kirill Lomov’s name did not appear on the social networks of the Russian Embassy in Bratislava either, even though the accounts are extremely active. But using his photo, we managed to place him at the Nitra commemoration event on the 77th anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising. The Russian embassy’s website also shared information on the participation of “an employee of the Russian Trade Mission in Slovakia.”

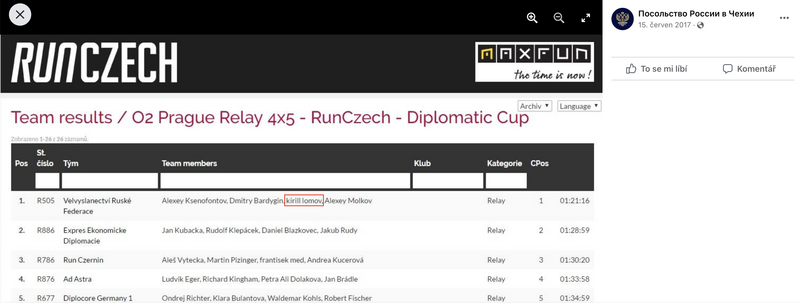

Lomov pursued his hobby, running, in Slovakia, and his name also appeared in registers of running races in the Czech Republic in 2016 and 2017.

In April 2016, he competed in the Diplomatic Cup for the Russian Embassy in Prague. The Russian four-man relay team eventually won the competition. They also beat the team from the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the U.S. Embassy. A year later, Lomov was once again a member of the diplomatic running team. Lomov also appears in photos from the International Student Ball in Prague during that period.

Source: Facebook/Посольство России в Чехии

Although Lomov officially represented the Russian Embassy, his name is missing from Czech diplomatic documents from those years. According to Czech journalist Ondrej Kundra, who has long covered the topic of Russian intelligence activities in the Czech Republic, there are several explanations for this. For example, there may have been an administrative mess behind this discrepancy— Lomov simply may not have reported to the ministry. However, it is also possible that he was not included in the diplomatic list on purpose. According to Kundra, the Russian embassy may not have been interested in putting him on the list. “I don’t think the Foreign Ministry does a lot of checking and verifying that everyone is reported on the list,” he added.

Moreover, those who are not full-fledged diplomatic but so-called technical and administrative staff are simply not included on the public list.

Slovakia and the Czech Republic are special for Russians

Both Slovak and Czech secret services often mention the activities of intelligence officers from two countries—China and Russia—on their territory. The Czech BIS has described them as a threat. Ondřej Kundra thinks that the region has more of a special resonance for the Russians. “They have historically ingrained long-term roots. Because of the long tradition of Soviet or Russian espionage, they feel they know the lay of the land.”

Libor Kutěj, the former deputy director of Czech Military Intelligence, says that the Soviets had built up very good positions in Czechoslovak society and had deep human ties with representatives of the security forces of the former Czechoslovakia. After November 1989, the Russian intelligence services took advantage of this. “Our reaction was delayed, and state authorities and institutions were until recently (specifically until the so-called Vrbětice affair) afraid to touch these privileges—namely, the number of diplomatic staff at the Russian Embassy in Prague, as well as the property of the Russian embassy and, above all, the incredible disproportion of accredited Russian diplomats in our country and Czech diplomats in Moscow,” offered the former intelligence officer.

Although the Czech Republic, and Prague in particular, is described as a favorite place for Russian agents, Ondřej Kundra adds that Slovakia may also have become more important for Russia after the September parliamentary elections. “By having a pro-Russian, anti-European government in Slovakia—an authoritarian government, a government that undermines the rule of law—the Russians may strengthen their influence on its politicians and try to make Slovakia another Trojan horse within the European Union, as they have already done with Hungary,” he warned. However, former intelligence officer Kutěj pointed out that the Russians are active in Slovakia mainly because of its membership in NATO and the EU.

ICJK sources close to Slovak diplomatic and security circles have confirmed that Russian intelligence services are very active in Slovakia. Their presence in Central Europe increased dramatically after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Russian agents seek contacts and connections not among disinformation actors, but also in the mainstream media; in academia; in the non-governmental sector; and, last but certainly not least, from the intelligence or security services of the state or from the ranks of their former members. And if someone solicits money, cash financial flows are hard to trace, security sources say.

The Russian Embassy’s Facebook page shared Lomov’s presence at the Slovak National Uprising celebration without mentioning his name. Source: Facebook

An ICJK source close to the Slovak secret services says that they have a good map of which Slovak representatives from which organizations “go on trips to Russia for quasi-conferences in Moscow or St Petersburg even during the war and have their travel paid for.” They travel there via the Kremlin’s close ally, Belarus. “They have visas arranged, everything is actually under the curatorship of the Russian embassy.” These are representatives of civic associations, alternative media sites, as well as towns and villages. “It’s all happening quietly, of course,” the source added.

The expulsion is a purely political decision

Although our sources confirmed that Slovak intelligence services are actively investigating Russian intelligence activities, their findings do not always lead to the expulsion of spies. “That intelligence does exist,” says a source close to the intelligence services. However, the next steps are decided at the political level.

An expulsion may also be blocked by a coalition partner, as Peter Kmec of Hlas explained to Denník N in 2021. In the interview, he said that the expulsion of Russian diplomats after the poisoning of former Russian agent Skripal was stopped in the spring of 2018 by SNS chairman Andrej Danko. According to our source, Danko had even threatened to leave the coalition, which would have meant the fall of the government.

A source close to the defense ministry told us that the former defense minister for the Slovak National Party, Peter Gajdos, had also received specific information about specific Russian intelligence officers with diplomatic cover who were carrying out illegal activities. “For political reasons, no action was taken against them,” the source added.

Although the defense ministry no longer belongs to the SNS, the latter is once again part of the new governing coalition, having joined Robert Fico’s fourth government, which was formed after the September elections. Both Smer and the prime minister’s rhetoric are now in line with that of Slovakia’s traditionally pro-Russian parties, and the country’s official communication is also beginning to change. Several experts interviewed by ICJK wondered what impact the pro-Russian orientation might have on Slovakia’s resilience against the influence operations and intelligence activities of other states.

The Dossier Investigative Center contributed to the research for this text.

The original Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

Lukáš Diko is the editor-in-chief at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK). An experienced journalist and media leader, he was previously director of news and journalism at RTVS and editor-in-chief of news at Markíza television.

Karin Kőváry Sólymos is a Slovak journalist at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak. Previously, she was an editor and presenter at the Hungarian channel of the Slovak public service media. During her university years, she was an analyst for the only fact-checking portal in Slovakia. She was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.