- We follow migrant paths documented with digital footprints and personal accounts

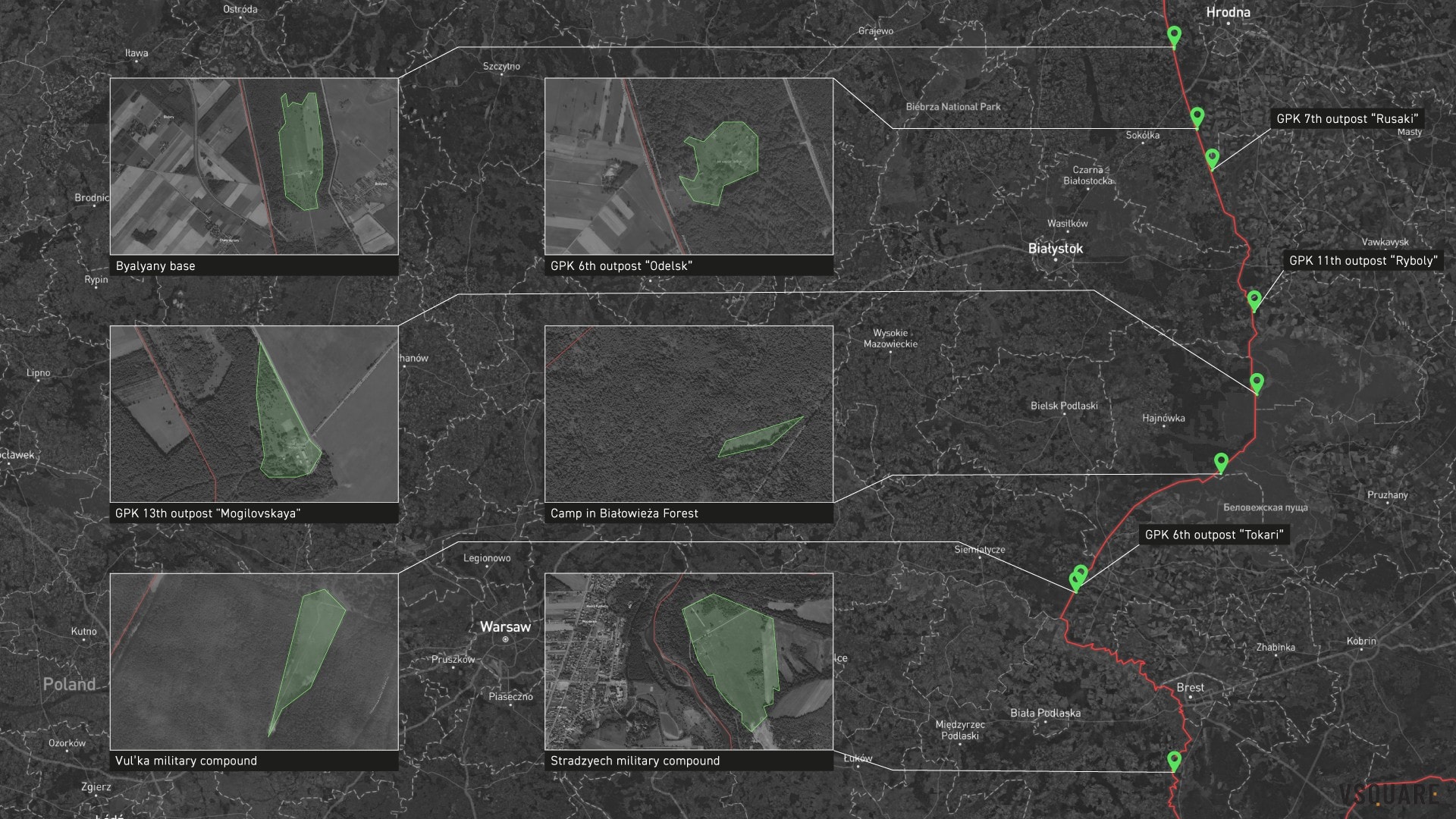

- Our investigation reveals locations of transit nodes used by Belarusians to smuggle migrants through the border and their connection to Belarusian military infrastructure

- Powered by the influx of people both coming from Minsk and these stranded at the border after expulsion from Poland, these assembly places turn into mass camps with dire conditions

- In a camp near Tokary, 500m from the Belarusian border post, deaths of migrants were documented.

Once it turned dark and temperatures dropped below zero, the journalist Rawand Qadir (name changed for protection reasons) began to tremble with fear. He was in the woods together with his wife and three children, while uniformed Belarusian guards herded them westwards towards the border. Only to have Polish officials turn them back eastwards: “If anything happens to my daughter I’ll die, I swear,” he wrote in a message.

For weeks, the situation on the Belarusian-Polish border had been tense and filled with human drama. Migrants and refugees are trying to enter Poland, to then move on West through Europe. Our research indicates that persons prepared to breach this border and then turned back by the Polish Border Guard are held in Belarusian military bases and training grounds. They are taken there by the Belarusian border guard – thanks to reports provided to us by Rawand Qadir and others in his predicament, we have been able to locate many such bases – one of these is in Tokari, close to the Polish county of Mielnik.

Once new arrivals are taken to these collection points, there is no turning back – they are forced to breach the Polish border, where Polish officials await to pack them into cars, ferry them back to the border and force them back across to Belarus. Where history goes on repeating itself: rounded up by Belarusian authorities, they are taken to military bases to rest a little and be marched off in the direction of Poland.

They will be forced to repeat this process even if their resolve fails them and they wish to return to their homelands. Anyone who resists is beaten and hounded with dogs.

Rawand Qadir’s family not only witnessed this brutality and ruthlessness but suffered it first hand.

According to Poland’s Border Guard service, since a state of emergency was declared in the region between 2 September and 30 October 2021, more than 27,000 attempts to breach the Polish border were “discovered”, with a mere 574 persons actually being detained. Border Guard officials claim all other attempts to cross the border were “thwarted”, even though almost 6,500 exiles and refugees officially reached Germany via the “Belarusian trail” in September and October of this year… Asked how the exact figures presenting these “thwarted attempts” should be understood – as persons or as attempts – the Polish Border Guard service refused to give a clear answer.

Photo: Karol Grygoruk / RATS Agency

The experience of Rawand Qadir and his family is one of thousands of such cases – his is simply better documented. Rawand is a Kurdish journalist – what happened to him along the way was recorded and shared with us live. In order to learn what was happening to refugees and migrants, we spent over a week on the Belarus-Poland border analysing information published online, as well as stories collected from humanitarian organisations and the migrants themselves in the region. We verified information published by the Border Guard Services, propagandist communiques issued by Belarus and content taken from migrants’ social media accounts. We identified the places they were being sent from, using satellite maps and telephone geolocation to link them to pleas for help sourced from the internet and humanitarian organizations.

The evidence we have been able to gather shows the tragic fates suffered by those attempting to cross the Belarusian-Polish borders.

Military Training Grounds

We talked with Rawand about his journey using a digital communicator service.

Have you been to a Belarusian camp?

It was more a military camp, a place for soldiers – Rawand answered.

We pore over maps and photographs in order to establish that during their ordeal upon the Polish border they had spent time on a military training ground in Stradzyech near Brest.

It is futile trying to find out anything about it online – maps show it to be a sports field-like area, relatively tiny compared to other Belarusian military facilities. Archival satellite images we discovered on Google Earth show, among other things, a large, unmarked landing strip, at times covered over with tarpaulin, and something resembling an armoured vehicle or tank.

On 4 October 2021, human rights defenders were told this is where some 100 persons were forced to camp and then be taken under Belarusian guard to the Polish border. The lucky ones are taken to a spot where the river Bug ends and a simple, grassy borderland begins – here, in Vuĺka, Brest, Belarus, they prepare to breach the border by climbing over barbed wire and begin their trek across the EU – unless they stumble upon Polish border guards who “thwart” their attempts and turn them back towards Belarus.

We find the camp in Vuĺka, Brest on Google Earth thanks to a film clip posted by one of the migrants. This is one of several unmarked military training grounds, which cuts into the borderland woods. One of the buildings upon it flies the Belarusian flag, border guards dressed in camouflage uniforms sitting beneath it. Groups of migrants rest on the grass under the military men’s watch, children playing on ladders. They have not yet experienced the hardships of tearing through Polish forests in worsening weather.

Then there are the unlucky ones forced to cross the river Bug. If they cannot afford to pay for help in crossing the waters, they have to swim for it. If they refuse – they are forced to do it anyway. On 20 October 2021, 50km from Stradzyech near Woroblin, the body of a Syrian teenager (19 years old) was fished out of the river Bug. The person who had accompanied the drowned man during the crossing testified that they had both been pushed into the river by Belarusian forces.

How did Rawand and his family first try to cross over into Poland? He used Google Translate to keep in touch with us via Facebook Messenger:

“On the night, a car took us – 4 people – to the Polish border. When I got down I was so scared for the first time. My kids and I didn’t see anyone in the dark for one meter. Both of my little kids were holding hands tight and they were so scared. My little baby was with her mother, we were 2 hours away from them. We arrived at the end of the Belarusian barbed wire – when someone tried to break the wire, the Belarusian police came within 5 minutes. – Poland or Belarus? We all said – Poland.”

“They took us to the road and stopped some other cars, we all were sent by car to the Polish border. On the Polish border, the police told everyone to turn off the mobile phones and the children’s voices. We marched 4 km away (into Poland) and we had a rest for a while, the person I was in contact with within Belarus (smuggler) gave us a place to come to the car (but it didn’t work out). I stayed in the forest that night, the next day another family and two young men went to another place to look for a car – in our place, there were police everywhere. We were tired, we just stayed, then we agreed to leave the place. We gave up one kilometer away to the Polish police, we rode a police car; they questioned us a lot and we asked them to help us. Our children were so thirsty that I hurried to them to get water, and the Polish police gave me water, and we were sent to the Belarusian border again.”

“Belarusian police came carrying three young Arabs who also rode a car with us to the Belarusian camp [army base – Stradzyech or Vu’lka]. There were many families in the Belarusian camp. They were from Iraq, Turkey, Yemen, Syria but most of them were Iraqis. They were waiting until midnight, Belarusian police said they were leaving at 2 o’clock at night. My family begged us to go back to Belarus. We all asked, we wanted to go back but they refused – we had to go to Poland, even a Turkish woman who had broken leg and had surgery again. We went to Poland at night, we tried three places at night, we didn’t go out, we went back to the Belarusian camp.”

Thank you for killing us with the governments

This is one of many such cases. Families with children are least likely to succeed in crossing the challenging terrain of the woodlands along the River Bug.

Since the start of October, numerous pleas for help have been submitted to various organisations from persons who were last identified as having been at the military ground close to Brest.

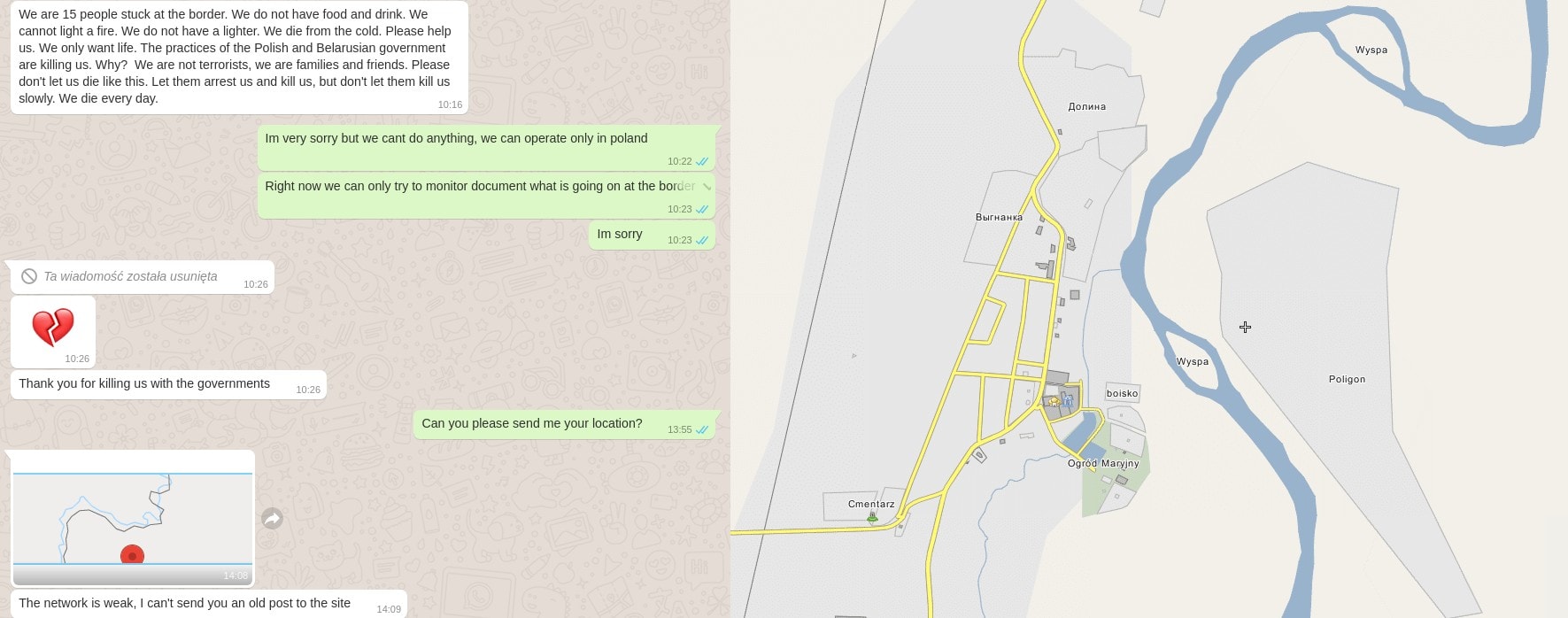

“We are 15 people stuck at the border. We do not have food or drink. We cannot light a fire. We do not have a lighter. We die from the cold. Please help us. We only want life. The practices of the Polish and Belarusian governments are killing us. Why? We are not terrorists, we are families and friends. Please don’t let us die like this. Let them arrest us and kill us, but don’t let them kill us slowly. We die every day” – this message was received from a Syrian telephone number (unavailable at present, the identity and current state of the author unknown).

A relative of another family wrote: “Please help, my family is stuck in a Belarusian forest, soldiers won’t let them retreat towards town and return to our homeland, they have no water, food, are freezing; accompanied by small children. Please take them back to town or provide them with food (…) Their money has run out, this is day 10 they have been sleeping there… They say they are being forced into the river [the river Bug flows close to Stradzyech – Ed.]”.

An Iraqi man wrote: “Sir, please help us, I am at the border with my family, I have two daughters of 2 and 3 years of age, we are in the hands of the Belarus police, they will send us to the border today – not letting us stay – please help, this is the fourth time, we will die there”.

Those on the receiving end of such desperate appeals for rescue are helpless – activists only help those who have been able to cross the Polish lands covered by the state of emergency – they are unable to get anywhere within three kilometres of the border, much less help save anyone from the violence being unleashed by Belarusian border guards. They patiently try to explain to those trapped on the border that they cannot do anything other than inform the Red Cross and the UNHCR – the UN’s Refugee Agency – and there is no way of telling how soon a response will come. Someone snaps back “Thank you for killing us with the governments” from one of the groups before contact with them is lost.

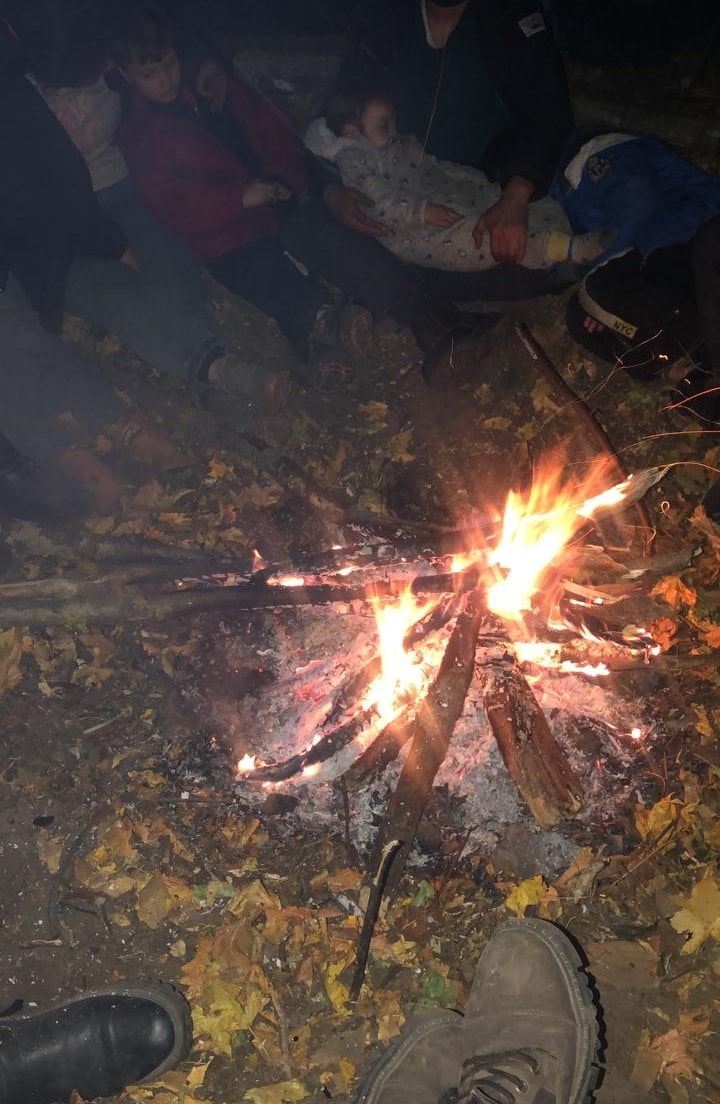

Two sisters from Yemen set off from the military training ground – one is 6 months pregnant, accompanied by a three-year-old child. An African organisation that rescues victims of human trafficking, informed about their plight by a third sister, share with us updated transmissions regarding their position. First, this is at the training ground in Stradzyech, then the woods in the Polish county of Tokary, 1.5km from the border. This is as far as a group of migrants, mostly made up of women and young persons, had managed to get – come the morning, temperatures drop to 1 degree Celsius, so the women light a campfire to warm the children. 20 minutes later, they drop another pin – having instantly been spotted, they are “turned back to the borderline” by Polish officials. “They got to Poland, but Polish border guards put them on a bus and left them on the border with Belarus”, according to their sister.

The sisters from Yemen, Rawand’s family and others whose attempts to get through the Polish perimeter have been “thwarted” once more meet in Tokary, having first met on the military training ground in Stradzyech.

Tokari

Rawand’s reports indicate that following failed attempts to cross the border into Poland at various points, his family ended up in another camp. We have been able to establish that this was in Tokari – a small Belarusian settlement right by the border. The largest object in the village is the 6th base belonging to the Tokari border guard division.

The camp in Tokari, unlike the training grounds hidden in the woods where migrants are taken under cover of night, is located right on the border. This is an image taken from Usnarz Górny, the first and best documented migrant camp that emerged already in August. Group of stranded people sitting on a road bordering Poland and Belarus, right by the razor wire fencing, an arm’s length from Polish soldiers. This is where groups of survivors end up, having been forced out of Poland several times by the Border Guards.

The nearest Polish village is a mere 500 metres away and this is where, for a fortnight, regular attempts to “violently force the borderline” are made by large groups of people camped out there.

A Belarusian border camp post is a mere 500 metres away on the other side of the border. They constantly keep watch on the migrant camp and monitor reactions from the Polish army.

Rawand Qadir and his family reach Tokari on the night between 8 and 9 October. They are frozen, exhausted and starving. Yet this is no reason for the Belarusian border guards to let them rest up. On the evening of 10 October, Rawand writes:

“Now Belarus says my friend must press the border with Poland. If didn’t I kill you. Now [they talk] with me. Now all families must go to the border with Poland and press. Police Belarus record. Soldiers Poland record all the time”. Belarusian soldiers are constantly watching from the woods, and the Polish military are within easy reach – only a wire fence topped with bales of barbed razor wire separates the two forces.

Rawand’s messages are one of the few direct reports from those forced to breach the border, unedited by propagandist media outlets. The official state-sanctioned media in both Belarus and Poland have a monopoly on reporting from the border about the fate of people “suspended” between the Polish region covered by the state of national emergency, which is closed to reporters, and the Belarusian “sistema”, a buffer strip of land guarded by the KGB.

Clashes between migrants and the Polish border guards are recorded by Belarusian officials, and then broadcast in pro-government media outlets. Belarus’ Sputnik reports that “Poles are using weapons to chase off the refugees”.

Polish officials are also recording and sharing the content with Poland’s mainstream media outlets. niezalezna.pl has published reports about “aggressive migrants storming the border” based on information from Tokari.

Rawand sends us more video clips – one shows a person awkwardly trying to knock down a bale of barbed wire using a long, metal pole. On the other side, numerous Polish uniformed officials can be seen watching. Another clip shows a wide gash upon a person’s hand produced by razor barbed wire – 150km of razor wire fencing was erected along the Polish- Belarusian border in August of 2021.

Pin

Towards the end of the first week in October, following a brief period of warmer weather, temperatures in the region dropped to below zero degrees Celsius at night.

We earlier reported how in preceding days Rawand Qadir and his family, along with 23 other persons, crossed the Polish border for the first time. They were assisted by Belarusians, and then had to manage on their own. Polish border guards caught them each time and then forced the whole group back into Belarus.

Up to this point, the story of his journey has been pieced together from later conversations with Rawand and his notes, along with reports provided to us from other members of this group.

On 8 October 2021, Rawand sent a message to his family and friends that his family was stuck. This was a pin dropped on a digital map which included his coordinates. This is the easier way of pinpointing the location of a cell phone signal and its owner.

The pin was dropped on a border road strip close to Tokari. On the Belarusian side of the border. Rawand dropped this pin and sent it mere moments after he was turned back across the border by Polish border officials.

Those close to Rawand began to make contact with humanitarian aid organisations. They gather such requests to help people lost and trapped in woodlands outside the emergency state zone. Once they are able to locate those in need of help, they can reach them with clothing, food and medicines, call ambulances and document requests for international protection. With the aid of emergency telephone lines the organisations establish, we have been able to contact Rawand via WhatsApp.

For the next few days, we were able to continue monitoring what his family were going through, in moments when Belarusians allowed him to charge up his phone battery using a power bank – to no more than 20% battery capacity.

Usnarz every 5 km

As we have previously mentioned, for almost a week Rawand Qadir and other persons in his group tried to secure help in getting out of a dead-end they had found themselves in.

A number of families are shoved back and forth across the border between Poland and Belarus by officials representing both governments.

Their experience is far from extraordinary. According to localization data extracted from humanitarian aid requests from the Polish perimeter, provided to us by Grupa Granica (Border Group / a coalition of NGOs providing humanitarian aid to refugees and migrants), large groups of refugees can be found camping every five to ten kilometres in the triangle between Belarus, Lithuania and north of Bialowieza Forest (but always strikingly close to military bases). Inhabitants of the border areas report about camps for over 200-300 people just at the outskirts of the Polish part of Białowieża Primeval Forest. The first reports of deaths in the camps are published when we close this publication.

They find themselves in a situation similar to Rawand and his group: Polish border guards won’t let them enter Polish territories; Belarusian authorities do not allow them to move in any other direction.

These are human beings no one is able to help; the Belarusian government only allows the Belarusian Red Cross to enter for propagandist purposes, such as deliveries of parcels for those camping in Belarus near Usnar Dolny. Polish authorities do not allow UNHCR officials to come near the border, even though Polish organisations, upon requests from refugees, keep these institutions informed about the experience of those trapped at the border.

Since mid-September, social media and the email accounts of Grupa Granica volunteers have been flooded with messages relating to persons missing or with requests for assistance from those lost on the borderlands and their relatives.

On Saturday 9 October, a recording is sent to us at dawn: a group of people are sitting round a Belarusian border post and lighting a campfire. Everything is covered in frost. Rawand’s group has no water or food. Activists inform him they have let UNHCR know about his predicament and that 13km north along the border line there is an open crossing he could reach and ask for asylum, by surrendering to the border guards.

Unfortunately, they have no means of moving along the borderline. “Belarus will not let me in,” Rawand writes, “Belarusian police only let us into Poland. Can’t move left or right. Only Poland, not back”. Belarusian authorities allow refugees to move to the right or left of the fence, but no further than 500 meters. Rawand and his family are stuck by border post no. 249.

In a photo taken on 9 October 2021, Rawand’s family are sitting by a dying campfire, tiny Noor asleep on her father’s knees. That same night, Rawand sends photos of a police van watching them from the Polish side. Belarusian guards watch from behind some trees. In just one day, their group has doubled in size – from 24 to 48 persons, which includes those newly “forced out” of Poland.

Collective pushback

Frosty weather begins to bite. By Sunday, the group numbers 75 persons. The camp runs out of drinking water. They receive some from Poles. Rawand sends us a recording of another man begging for more water for his child. He is out of luck – Polish soldiers, troubled by the requests, only grin sheepishly. The group buys food from the Belarusians with the last of their money.

The group includes numerous children – Rawand sends documents belonging to a five year old in the camp suffering from cerebral palsy.

On Monday 11 October, they run out of firewood. Belarusians refuse to sell them any more food. Rawand begs for contact with media outlets. The video recordings he sends show dejected refugees wandering along the borderline. Yet, they make another attempt to cross the border. This time, successfully. At 4.30pm, something happens – Rawand sends a short voice message: “We are in Poland! I beg you, come.”

Rawand reveals his location on the Polish side of the border and sends the films he shot during the crossing: members of their group use long steel poles to knock the razor wire fences to the ground. Migrants cross over to the other side and lie on the ground with their children. Border guards raise their firearms and order the group to sit by the fence. Everything happens almost peacefully. The line then goes silent for a while.

At 6.30pm, Rawand drops another pin from the route by the Polish town of Czeremcha.

“What is happening?” he asks. “Huge police cars. I am here with my family. All families, 12 or more. Do you know where they are taking us? Where? To Poland? To camps?”

His pin gets closer to the border checkpoint in Czeremcha. Activists inform us that it seems to be getting closer to the border guard checkpoint.

Rawand sends his last message at 6.20pm: “Should I turn my phone off? Please. I am scared.”

“We cannot help there, it is a state of emergency territory. We are sorry,” activists respond, though the message goes unread. Rawand’s phone falls silent.

Activists call round refugee centers and Border Guard offices, trying to ascertain where Rawand and his family are. No answer. For a week, there is no further news on his whereabouts.

The mystery of his disappearance is solved when Rawand contacts us a week later, on 18 October 2021. In spite of problems, he has reached Germany with his whole family and is staying with his sister in the western lands. He plans to move to a refugee center and apply for asylum. Before he is quarantined without access to a phone, he shares with us what has been happening all week.

On 11 October, police vans did not stop at the Border Guard checkpoint in Czeremcha. They drove along the River Bug and Tokari for two more hours – almost 130km – beyond Białystok as far as the border crossing in Bobrowniki, where a Border Guard office receives asylum claims from a chosen few.

Yet instead of going to the refugee center, the buses turned north down side roads and unloaded the foreigners – almost 40 persons – on the border of a Belarusian “sistema”, which in this part of Poland begins next to the village of Łapicze.

Rawand indicates on a map where following the trip from Tokari the Polish officials shoved them through a hole in a fence back into Belarus. “There were no Belarusians there,” Rawand says. “Uniformed officials walked with us across the border, leaving us there with the words: go back to Belarus.”

This practice of informally expelling foreigners (without proper procedures being followed) is known as “push back”. Yet, despite push-back, Rawand was able to get a ride to Germany soon after, from almost the same spot they were dropped off by Polish officials.

A few days later, most of the families from the group expelled from Tokari to Krynki arrived by car to Germany. Three families remain behind – those whose relatives back in Iraq have run out of money and cannot support them to pay smugglers.

When we talk in Germany, Rawand recognises the faces of the members of his group in recordings shot in Poland by the TVN channel on 14 October in Hajnowka, 70km from Krynki. A family with six children, despite pleas for protection in Poland, are once again loaded onto a truck and sent into the depths of the Białowieża Forest, a place covered by the national emergency restrictions. Their further whereabouts remain unknown.

People who remain uncounted

The dramas suffered by the Qadir family and thousands others like them take place in the region covered by the national emergency restrictions. Reporters, members of parliament and NGOs have no access to it. All we can learn about their fates comes from the “pins” they drop on internet maps, messages on Facebook groups and contact made with local people.

The authorities prefer to remain silent, ignoring or dismissing questions from human rights organisations. This can be seen in the example of Rawand and his group – activists tried to move heaven and earth to confirm the location and status of his family and all the others – this is how they learned that persons detained and “returned to the borderline” (if we are to believe Polish Border Guard reports, these number in the many thousands) are not recorded or listed by Polish authorities. No trace remains of their presence on Polish territories.

On Saturday 9 October 2021, the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights sent the RPO and UNHCR an intervention regarding the group located in Tokari based on documents gathered by activists.

“This matter relates to two foreign families, which on the night of 4 October 2021 were detained by Polish Border Guard officials close to Tokari, and then were forced to cross the border towards Belarus without any due legal process being followed, such as procedures binding them to return, or giving them access to international protection. These families were not given essential aid, even though the group included a heavily pregnant woman and four small children (1, 3, 6 and 8 years of age). […] Following the illegal push-back of both families out of Poland by Polish officials, and in relation to brutal actions by Belarusian border authorities, both families are now forced to camp close to the border on the Belarusian side. They receive no assistance, being left with no food, water or warm shelter even though the temperatures drop to below zero Celsius during the nights. Belarusian guards forbid the families from withdrawing into Belarus or moving along the borderline to the official border crossing 17 km north of their location. Polish uniformed officials (most likely Polish Armed Forces soldiers) forbid them from crossing into Poland in order to apply for international protection.”

No answer has been received by now. Some answer is sent to the political offices of Franciszek Sterczewski, which on Monday – the day Rawand was arrested with his family – intervened in the same matter, asking Border Guards about where the journalist was being held in Poland along with his family:

“Dear Member of Parliament, in answer to your request for information, I state that based on tele-informatic systems of the Border Guard we have tried to identify the person mentioned in the aforementioned document. As a result of our review, it was confirmed the Podlaskie Border Guard Department is not pursuing any action with regards to these foreigners. We have no further information about the legal situation these foreigners find themselves in.”

This answer is signed by the Commander of the Podlaskie Border Guard Service – colonel Andrzej Jakubaszek.

On the Belarusian-Polish border. Source: Karol Grygoruk / RATS Agency

On Tuesday, the Border Guard published a report covering the previous day: “On Monday 11.10 on the border, we recorded 605 attempts to breach the border illegally. 13 illegal immigrants were detained. The remaining [592 – ed.] attempts were thwarted.” The group which disappeared on 11 October 2021 by the border guard checkpoint in Czeremcha included at least 70 adults and 16 children.

We can only speculate that 7 of the 592 “thwarted” attempts that day include Rawand’s family. If they were turned back a total of four times – then this seven person family is responsible for 28 of all 27,000 “thwarted attempts”.

Four attempts in these statistics would have been made by the tiny, year-old Noor. Six children of the family which ran out of money for smugglers, and which was turned back in the Białowieska Forest for the fifth time, represent 30 “thwarted attempts”.

Refugee or migrant

A photograph taken before departure from Turkey shows a family dressed in European fashions smiling and posing in a park. Rawand and Leyla are a married couple with three small children. Their sons are six and eight years old, Noor – a smiling girl in a pink dress – is only a year old. Before their escape, they lived in Irbil, a relatively safe capital of the Kurdish autonomous region. They will take siblings along the route to Poland.

Why, like thousands of other Kurds, did they leave Iraq and head for Europe?

Iraq is the main origin of migrants passing through Belarus – according to data issued by Frontex, only in July and August of 2021 this was the path taken to Europe by 3244 Iraqi nationals. Though there is no armed conflict taking place there, as there is in Yemen or Syria, Iraq has 2 million internal refugees, and is more dangerous for some than it is for others.

“Iraq has been the site of ethnic and religious conflicts for decades, forcing people to flee,” according to Iwo Łoś from Grupa Granica. “For an example, in the woods recently we met a multi-generational Yazidi family from Iraqi Kurdistan [the slaughter of Yazidi nationals by the Islamic State in 2014 was recognised as a genocide by the UN – Ed.]. In addition, Iraq and Kurdistan are politically unstable and particularly unfriendly towards reporters and political activists from all sides.”

In 2019, UNHCR issued a memorandum which stated persons at risk included those who oppose the national government of Iraq, as well as the government of the Kurdish autonomous region – especially journalists and media employees as well as members of competing and opposition parties. This is the case with Rawand, who worked as a cameraman for an online portal connected with one of the largest Kurdish parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan.

“The new Regional Kurdistan Government has really restricted freedom of speech,” according to Ragaz Kamal, founder of the 17Shubat group for human rights (the name refers to protestors massacred during the Arab Spring). “Since last year, TV stations have been attacked, 100 activists and journalists have been arrested by Asayish [Kurdish security forces – Ed.], and a number of them sentenced for as much as six years in prisons.”

Rawand is a member of the Kurdish Journalist Syndicate which publishes annual reports covering repressions of journalists in Iraq: “42 arrests, 32 attacks, 8 beatings, 4 cases of threats, among others. Attacks upon the media affected 315 organisations and journalists in all of Iraqi Kurdistan,” according to their 2020 report.

In August 2020, Rawand’s colleague vanished from work while reporting from opposition demonstrations. Rawand states that he too was arrested twice and placed under police supervision. This bitter scenario is made worse by the coup and purges in the PUK party, whose leader becomes persona non grata, and his collaborators have to escape Kurdistan. As a politically engaged Kurd, Rawand is not safe in Turkey either.

With his whole family, they buy Belarusian visas in the belief they will allow him to ask for asylum in Europe and join their family in Germany. Iraqi nationals have one of the “weakest” passports in the world, able to enter five countries without visas, and with visas to enter 16, none of which are in Europe (Polish passports, for example, allow easy access to 130 countries). This is why the Belarusian visa, issued by “tourist offices” collaborating with the Lukashenko administration, are the only way for Iraqis to reach Europe. Such a journey costs 4000 euros per person, which includes flights, transport across the border and smuggling in cars from the Polish border onwards.

“I was arrested by Polish police two days ago,” Rawand writes the very first day. “I showed them my passport and my press ID. They said – go back to Belarus, no Poland for you. Polish and Belarusian police film us,” he adds: “In Iraq, I am a journalist. You know how it is for journalists in Iraq. I cannot go back.” Rawand also displays his IFJ – International Federation of Journalists – ID and that of the Kurdish Journalists Association, plus his family’s passports and contact details for his family. These documents allowed us to verify his version of events.

“As a journalist connected with a party which rivals the Kurdish government, Rawand would meet two criteria for international refugee protection programs. This is to me a very obvious case for an asylum application, especially considering the UNHCR memorandum,” according to Iwo Łoś. “All such cases should be reviewed individually by the Polish authorities, which have far greater means for verifying such stories than journalists and human rights defenders.”

And yet neither Rawand nor other Kurdish opposition activists get such opportunities. Much like Yazidi refugees escaping persecution in war torn Yemen, many of which also reach the Polish-Belarusian border. Polish officials “push back” everybody, returning them to the border line and handing them over to Belarusians, who then once again chase them Westwards.

Post scriptum

Friday 15 October – a week following the first message from Rawand, who by then is on the way to Germany – another message is received by the Granica Group.

“Help! We cannot go back and have to walk to Poland” according to some Yemeni nationals.

“How many of you are there?”

“Almost a hundred people,” they reply.

They add a pin from Tokari to their message.

That same day, a Kurdish man sends a film clip from the border post number 249. Behind the tree line, among some falling leaves, Belarusian border guards light a campfire. Friends are shielding the cameraman, so the Belarusians do not know he is filming. The same person will post a film where another group clamber over razor wire fences using long poles. On the longer video delivered to us, he managed to register the masked Belarusian soldiers lurking behind the group.

The next day, the following post appears on the Border Guard Twitter page: “70 foreign nationals yesterday – 15.10.2021 – tried to force the Belarusian-Polish border at a spot protected by the Border Guard Checkpoint in Mielnik. We defended the border along with soldiers #WojskoPolskie”.

In spite of the efforts made by the Border Guards and Polish soldiers (#WojskoPolskie), five days later the author of this film clip reached the German border and asked for asylum.

On 23 October 2021, president Andrzej Duda signed the so-called “removals statute”. This legislation makes it completely impossible for asylum applications to be made by persons who reached Poland by breaching the “green border” and not via official border crossings (access to which is blocked by Belarusian officials, moreover, refusing asylum applications on Eastern borders has been a constant practice ever since). Grupa Granica representatives warn this legislation is incompatible with the Geneva Convention.

On 29 October, 23-year-old Gaylan Dler, died reportedly from diabetes due to lack of drugs and malnutrition. A film posted on Facebook shows his dead body lying close to border barbed wire, Polish soldiers looking from another side. He died in front of post no. 247, 500 meters from the place Rawand’s family was held.

A new group of migrants has already reached Tokari.

Filip Wesołowski contributed to this article. He is a researcher and OSINT analyst, member of INTERPRT project dedicated to forensic analysis of international environmental destruction cases.

A senior OSINT researcher and data analyst at FRONTSTORY.PL, Julia Dauksza has participated in many cross-border investigations. Previously, she collaborated with NGOs in Poland. She has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2021, 2022). She was the recipient of the 2023 Bertha Challenge Fellow.