Cypriot shell company Saxian once owned a fifth of Slovak company giant Penta’s healthcare business. Years ago, it also put money into a company that Dutch authorities branded a fake bank before shutting it down and putting its boss in jail. It had promised its clients to circumvent international anti-money laundering rules. Oligarch Norbert Bödör made tens of millions from Saxian, and the Bödors are now suing the Netherlands for four million euros from the fake bank.

But in doing so, they confessed to involvement in both the Cypriot Saxian and the anonymous Liechtenstein-based Betlem Foundation. We have discovered that the transactions took place at the end of 2017 and beginning of 2018, just at the time of the sale of the daily newspaper Nový čas, over which Norbert Bödör claimed he had influence in an encrypted communication with business tycoon Marian Kočner.

The legal battle by the Bödör family against the Dutch state was successful. On December 12, the court ruled in favor of the Cypriot shell company Saxian. The Netherlands will have to give the money back to the Slovak oligarchs.

In this article you will read:

- What the fake bank Custos is and how Bödör’s money ended up in it.

- Why the Bödör family is suing the Netherlands for millions.

- Why the Bödörs wanted to collect millions in an Irish safe deposit box and why they used a dubious “bank” to do it.

- Whether it could all be linked to the effort to take control of Nový čas (New Time), a tabloid newspaper, which was finally bought by Penta earlier this year.

Custos Trust posed as a discreet bank from the United Arab Emirates. Its advertisements promised clients that the money they put in would remain invisible to authorities. And if banking supervisors, police, or other institutions came knocking on its door, it would refuse to cooperate with them.

Several clients have taken advantage of the offer. They have invested more than 4.2 million euros in the bank. Of this, the absolute majority—exactly 4 million—was sent by the Bödör family at the end of 2017. Their private security company, Bonul, was at its peak during the third government of Prime Minister Robert Fico. Bonul’s revenue, thanks to numerous state contracts, exceeded €50 million, and there was also talk of an amicable relationship between the oligarch Bödör and the chairman of the SMER party, Fico.

However, Custos Trust was not, in fact, some super-discreet Arab bank for the chosen few, but an ordinary Ltd. registered in the Czech Republic, without a banking license. It was founded by a Polish citizen, Przemysław Nieużyła, who was arrested in the Netherlands in 2018 for having a fake passport.

Nieużyła was brought to court. During the trial, the Netherlands also froze Bödör’s money. Denník N wrote about this in 2020.

The fake banker eventually got 30 months in prison and all the money was forfeited. The Cypriot company Saxian is now trying to collect it from the Netherlands. The litigation is not a civil case of Saxian vs. The Netherlands, but rather a part of the previous criminal process in which the money was forfeited. In Dutch criminal law (Wetboek van Strafvordering article 552a), agents can file a complaint with the court to ask forfeited or seized items or money back.

The Cypriot shell company has been linked to the Bödörs in the past, but they have not officially admitted to the connection.

Dutch newspaper Het Financieele Dagblad quotes Saxian’s lawyer Thom Dieben, who told a court in The Hague that the Cypriot firm is linked to the Liechtenstein-based Betlem Foundation, which of which Slovak businessman Miroslav Bödör and his family were the beneficiaries.

However, the four million euros in the fake bank account did not come from Saxian’s account, but from the account of the Prague investment company AVANT. Norbert Bödör has been a beneficiary of the private equity fund (called “AVANT Private Equity” until January 1, 2021), which AVANT manages, since at least 2018.

Saxian’s lawyer also said that, with respect to the financial transfers, the only link between the Bödörs, Saxian, and the Irish firm Detchant is Peter Šveda. Šveda, who is a high-ranking manager at the companies of financier Anton Siekel, strongly denies involvement in the case. He claims that the people behind Detchant only approached him to say they wanted to buy land in Asia from Siekel.

Until October 2023, Šveda also managed Siekel’s company, through which he owned Nový čas. After that date, he sold it to the Penta group. Siekel acquired Slovakia’s largest tabloid newspaper in 2018. The dates of the acquisition suspiciously coincide with the dates of the financial transactions between Bödör’s Saxian and Ireland’s Detchant. It was also around this time that Kočner and Bödör wrote in Threema, an encrypted communications app, that the oligarch would take control of Nový čas.

Siekel’s manager, Šveda, denies that Norbert Bödör had influence over Nový čas or that he had knowledge that Bödör was trying to gain such influence through millions invested in a fake bank.

Bills of exchange, investments and shares of the Penta clinics

The court is due to decide on 12 December whether Bödör’s four million will be returned by the Netherlands. The Cypriot company Saxian claims it was defrauded by the fake bank. However, the local prosecutor’s office is opposed to the return of the money and says the origin of the money is suspicious. According to the prosecution, the company would otherwise have entrusted it to a regular bank, not one that promises to circumvent the law.

“In the Custos case, [Pole Nieużyła] targeted very specific customers: those who apparently could not or did not want to go to regular banks with their money,” the prosecutor argued in 2020.

Bödör, who is close to the SMER-SD party, is also on trial for accepting bribes in the Dobytkár (Cattle breeder) case. So, too, is he separately accused of setting up and orchestrating a criminal group in the Očistec (Purgatory) case and charged with bribery in three more corruption cases. In addition, he extracted millions of euros from a mysterious shell company and further appreciated them.

What is important for Slovakia is that, during the trial, it was confirmed that it is the Bödör family that is really behind the Cypriot shell company Saxian.

For years, no one wanted to admit to it, even though, back in 2020, it was linked to Bödör by an extensive investigation by the ICJK and other journalists associated with the Kočner Library project, for which we were awarded Open Society Fund Prague’s journalism award.

Saxian lent money to buy a hotel popular with SMER politicians, the Zlatý kľúčik (Golden Key). It was the murdered investigative journalist Ján Kuciak who first proved that Norbert Bödör was its real owner.

Since 2014, Saxian has also owned a fifth of the shares of Penta polyclinics. Back then, it was part of the company group Pro Care. Two years later, when he sold these shares to the Czech fund AVANT Private Equity (now just Private Equity) for EUR 4.8 million, Saxian paid the same amount to unknown people as dividends. The fund subsequently issued two promissory notes to Norbert Bödör for an identical amount. Later, Bödör received another promissory note from Saxian for EUR 3 million.

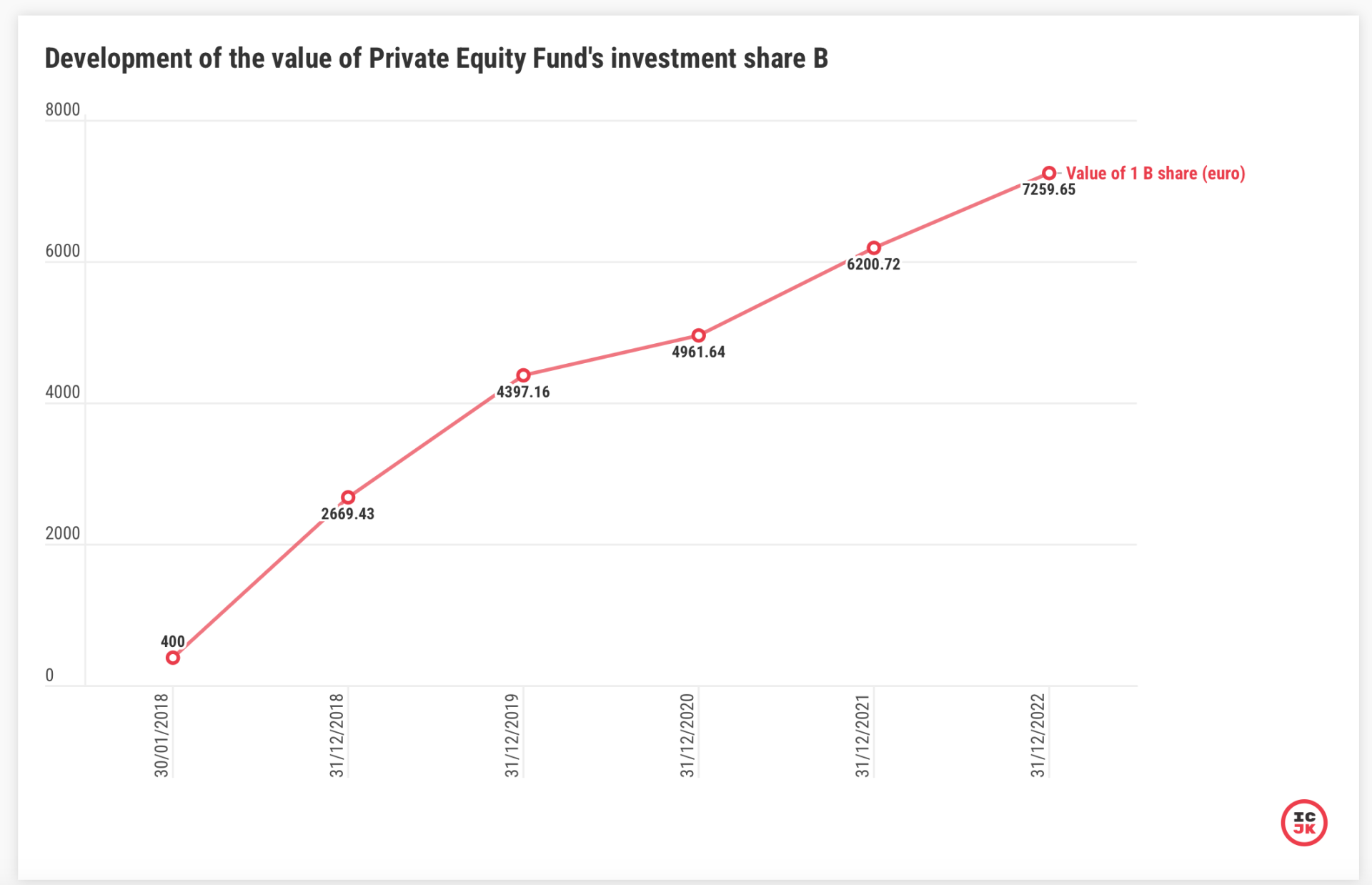

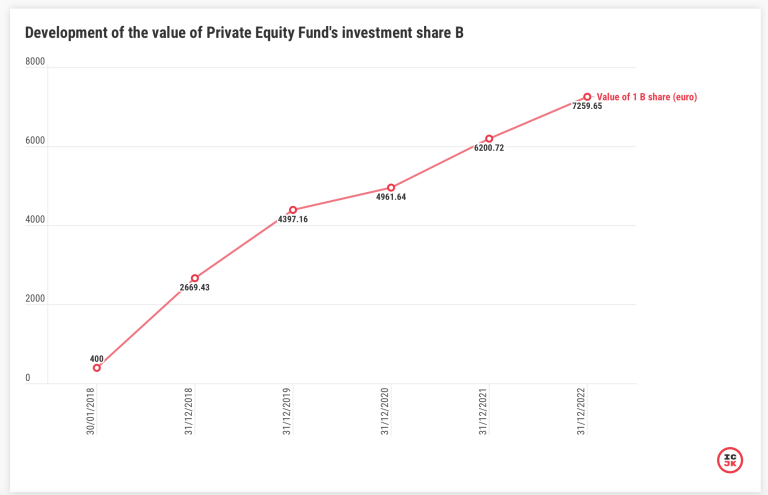

In all likelihood, Norbert Bödör used the proceeds to finance his purchases of investment shares in AVANT Private Equity. This was a very profitable purchase, because, by the end of 2019, some of these shares had appreciated more than ten-fold in value, meaning Bödör could have earned as much as EUR 30 million. From 2019 to 2022, the value of these shares has again increased by a further almost 21.5 million euros.

Foreign shells

In 2018, Bödör received another promissory note for €11.06 million from the Czech fund AVANT Private Equity. At the same time, according to Saxian’s accounts, this Cypriot shell reduced its debt to the mysterious Liechtenstein-based Betlem Foundation by the same amount.

Betlem is the parent company of Saxian and its owners could not be traced from open sources. However, in 2020, Dutch prosecutors proved that Miroslav Bödör, the recently deceased father of Norbert Bödör, was the real owner of Betlem. Today, Saxian also admits ownership.

We have repeatedly sent questions to Norbert Bödör via his lawyer Marek Para. He had not responded by the deadline.

The fake bank, which in reality was the Czech Ltd. Custos Trust, was set up by Polish citizen Przemysław Nieużyła in September 2016. In 2017, €4 million from the Bödör family flowed into it. It is that €4 million that is now claimed by Saxian.

The money did not come from Cyprus. Saxian entered into a loan agreement with Detchant Limited, an Irish company. Fake bank Custos therefore had a legal relationship not with Saxian but with Detchant.

However, the money was sent by the Czech investment firm AVANT directly to Custos. Saxian’s lawyers are arguing to the Dutch courts that this was a form of repayment of a loan between Saxian and AVANT. That is, AVANT owed Saxian something and repaid it by sending the money to Custos.

Infographic: the alleged purpose of the accumulation of funds in Detchant was to invest in land owned by Anton Siekel. However, the dates also coincide with another of Siekel’s investments: the purchase of Nova čas.

According to Dutch newspaper Het Financieele Dagblad, a lawyer told the court that Saxian did not act in bad faith when it transferred millions to Detchant. “Will the state take the money without Saxian being convicted or investigated?” the lawyer asked the justices. “This is the world turned upside down. Saxian has never been suspected, prosecuted or convicted.”

Prosecutor Nora Achahbar, on the other hand, says it is “undetermined” whether Saxian is the victim in this case. European money laundering rules, she says, require Saxian to prove that the money came from a legitimate source.

The Czech investment company AVANT did not respond to ICJK’s questions due to confidentiality obligations.

In its statement, AVANT claims that “Private Equity Investment Fund with Variable Share Capital, currently has no legal relationship with Saxian and, according to the records of the fund administrator, has never accepted or provided any payment to a person with the name Bödör.”

However, this does not contradict our previous findings that the AVANT Private Equity Fund issued at least one promissory note for €3 million and one promissory note for over €11 million to Norbert Bödör through an intermediary. It is also not inconsistent with the findings of the Dutch law enforcement authorities or even with the claims of Saxian’s lawyer, as the Cypriot shell insists that the €4 million that came into the fake bank from AVANT belongs to it.

Slovak advisers

According to the Dutch prosecutor, the money could be recovered by the Irish Detchant, as it was Detchant who was directly defrauded by Custos. Officially, Saxian only lent the Irish company the money.

However, this is impossible. Custos is in liquidation. Nobody even knows where Przemysław Nieużyła, a Pole, is today. He served two-thirds of his 30-month sentence while in detention and went free.

Saxian could still recover his money from the Irish company Detchant, but according to Saxian’s lawyer, the company “has no money.” According to the Dutch daily Het Financieele Dagblad, Detchant was set up specifically for investments in Asia and is otherwise inactive.

In a previous criminal case, the Dutch authorities also questioned the owner of the Slovak consulting and auditing group VGD, Marian Škorník. He was allegedly an advisor to the late Miroslav Bödör and it was he who allegedly organized the transfer of funds around the fake bank, Custos Trust. Škorník claimed to Dutch investigators that Miroslav Bödör arranged the whole transaction.

“It is difficult to imagine that Bödör, who, according to Škorník, coordinated the entire complex transaction, was not aware that anti-money laundering rules were being circumvented and that contracts were being forged,” the prosecutor wrote in the original indictment against Nieużył, according to Denník N.

Neither Marian Škorník nor the other VGD official mentioned in the Dutch indictment, Erik Marek, answered questions from the ICJK about whether they could confirm that the Bödörs knew to what company they were sending their millions, or about who at the time controlled and was the real owner of the Irish company Detchant, through which the money flowed to the fake bank.

“As auditors and tax advisers, we are bound by confidentiality, which not only by law but also by the nature of the case prevents us from commenting on matters relating to our former or current clients to the extent that we ourselves would consider necessary to answer journalists’ questions fairly,” Marian Škorník wrote back. “At the same time, it has been our long-standing practice not to make statements to the media. We will remain consistent in this respect also with your journalistic questions, on which we will not comment in light of the above.”

Škorník, Marek, and their company, VGD, are close to the Bödör family. For example, they were the ones who registered Bonul, a Bödör family firm, which they sold in 2023, into the Slovak Register of public sector partners.

Did they want to acquire Nový čas?

The Bödörs’ dealings with the fake bank took place at the same time as the sale of daily newspaper Nový čas. The financial transactions are linked by coinciding dates.

The information that the tabloid was being bought from German media giant Ringier by the financier Anton Siekel was first publicly communicated on November 6, 2017. On the same day, the Czech AVANT sent €4 million to a fake bank on behalf of the Bödörs.

It is known from Kočner’s Threema that Norbert Bödör was interested in the tabloid. Threema is an encrypted communications app that Marian Kočner used to write messages to most of his contacts. It was decrypted from his phone after it was seized as a part of the Ján Kuciak murder investigation. Kočner is still under trial for allegedly ordering the murder.

Four months after the announcement that Nový čas was being bought by Siekel, Marian Kočner asked Bödör whether he owned the daily.

“Have you got the Čas yet?” Kočner asked on February 20, 2018. Bödör replied that he hasn’t yet, because the Ringier split is underway. Kočner then continued in a way that implies that both parties in the communication think that Norbert Bödör will become the new owner of the tabloid.

“Listen, and are you going to get Silvia Kucherenko to join the TIME??? She has one moronic show on the internet at Novy Čas,” Kočner continued a few messages later in the thread, referring to a Slovak model.

“Then it’s in the price :P,” Norbert Bödör wrote back.

Kočner returned to the topic on 6 March 2018, when the news was published that the Antimonopoly Office had approved the sale of Nova Čas to Anton Siekel.

“When are you going to get that ČAS under control,” Kočner wrote the very next morning.

“In my opinion about 5 to 6 weeks,” Bödör replied.

The rumor that Nový čas was in fact to be brought under Bödör’s control also reached Monika Jankovska, then state secretary at the Ministry of Justice, now a defendant in several cases related to judiciary corruption.

“[is it true] That Čas is Padre’s?” Jankovska wrote via Threema to Kočner on March 29, 2018. “Padre” was the nickname of the Nitra oligarch Norbert Bödör.

“Not yet,” Kočner replied, then quickly clarifying, “in 3 weeks.”

The sale of Nov čas was finalized on July 31, 2018. However, there was no political pressure or external influence on its editorial staff when it was owned by Anton Siekel. During this period, selected reporters of Novy čas were even part of the Kočner’s Library project.

Dutch investigators also mentioned Peter Šveda in the transactions around the fake Custos bank.

Šveda is a high-ranking manager of several of Anton Siekel’s companies. Among other things, he was, until October 16, 2023, chairman of the board of FPD Media—the company that owns Nova čas, which Siekel sold to Penta earlier this year.

Šveda himself denies that he had anything to do with Detchant or the complex financial operations surrounding it and the fake bank Custos. “I have no relationship with Detchant,” he said.

“I was not involved in the transaction,” Šveda continues. “I have been approached by potential investors of Detchant who have declared an interest in buying some of the properties that belong to our portfolio in Asia. We have had preliminary discussions about the possibility of a sale, but the transaction has not been completed.”

He explicitly rules out any knowledge that Norbert’s or Miroslav Bödör’s money was to be involved, or that these transactions were related to the purchase of Nový čas.

“I absolutely rule that out,” he also replied to our question whether the Bödörs had any influence in Nový čas during the period when it was owned by the company he managed.

The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.