Cover photo: ICJK 2024-06-12

Cover photo: ICJK 2024-06-12

Without knowing it, we fill up our tanks with biofuels every day. Biofuels have become an important part of transport thanks to European Union directives, according to which it is compulsory to add them to both diesel and petrol. And it is a billion-euro business. The big businessmen — the so-called biofuel barons — in Slovakia, Ján Sabol, and in the Czech Republic, ex-Prime Minister Andrej Babiš and many others, are making money from it. The chain of production (and money making) starts in agriculture, in the yellow fields where rapeseed is grown, and continues on through rapeseed processing into oils. Production ends in refineries, where biodiesel is added to fuel. Millions of euros also flow in from European Union subsidies.

Last year, according to our calculations, more than 12 million euros were made via direct payments to farmers alone. So-called bio-based ingredients have long been considered one of the solutions to reducing the impact of the climate crisis. We have taken a detailed look at the data on bio-components in Slovakia, the cultivation of oilseed rape and maize, as well as the share of so-called first-generation bio-components in fuel, from which the European Union is already withdrawing.

The road to the Sokolce agricultural farm in southern Slovakia is surrounded by a yellow sea. It is still only April, but the rapeseed is flowering earlier this year. In recent years, we have become used to this sight in many parts of the Slovak countryside, especially in the south, where most rapeseed is grown. These same rapeseed fields are the beginning of a billion-dollar chain of biofuels. The yellow flowers will be burned in internal combustion engines to combat the climate crisis.

In the agricultural cooperative of Sokolce near the town of Veľký Meder, we can see how this crop, often referred to as the yellow evil, is perceived by those who come into contact with it every day. Peter Lelkes, the head of the cooperative, and chief agronomist Mikulas Balogh have decades of experience.

“We started with around 100 to 150 hectares and now we are growing oilseed rape on over 600 to 700 hectares,” said Lelkes. It wasn’t always like this. “We came to cultivating rapeseed on Rye Island out of a certain necessity, which was triggered by a change in the production structure on individual farms and entities,” the cooperative’s chairman added.

The pivot to rapeseed came around the turn of the millennium, when rapeseed began to come to the fore also as a possible solution to the climate crisis. Although experts consider rapeseed to be a problematic crop, according to farmers in southern Slovakia, “in terms of maintaining soil fertility and as a pre-crop, rapeseed is one of the best crops.”

Michal Roháč runs a small farm and is dedicated to regenerative agriculture. He doesn’t plough, doesn’t fertilize, tries to minimize soil disturbance and takes a critical view of growing rapeseed. In his view, the agricultural subsidy scheme also plays an important role in the “rapeseed formula”: “We are talking about large farmers who farm hundreds to thousands of hectares, who receive a subsidy depending on the area they farm,” he explained. Using data from the Agricultural Payments Agency, we calculated that direct payments for rapeseed cultivation in 2023 amounted to more than 12 million euros.

The business of bio-components has been growing for years. Biofuels have been touted as one of the keys to mitigating the impact of the climate crisis. This is also the basis for the biofuel empire of Envien, owned by the Slovak businessman Ján Sabol. Envien is one of the largest biofuel producers in Europe and, together with its partners, covers the entire chain from cultivation to production. Envien’s long-standing partnership with Hungarian refining giant MOL, owner of Slovak oil refining company Slovnaft, also works to its advantage. Both refining companies blend Envien’s biofuels into their fuels. Some time ago, ICJK also analyzed Envien’s shareholding structure, which includes undisclosed Hungarian shareholders.

Ján Sabol’s group of companies is also involved in a joint business, Exata, which owns several agricultural cooperatives involved in, among other things, rapeseed cultivation. Exata has links to Slovnaft boss Oszkár Világi. The companies belonging to the agricultural brand Exata, according to data from the Agricultural Payment Agency (PPA), grew rapeseed on 1,500 hectares and received subsidies of approximately 160 thousand euros through direct payments for the year 2023. The PPA has also supported the company Poľnoservis from the Envien group in the past. In 2009 and 2010, it received more than 4.7 million euros from the state for the construction of a rapeseed processing and rapeseed oil production plant in Leopoldov.

Former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš is also an important player in the European biofuels business thanks to his company Agrofert. Babiš is known in the Czech Republic as the yellow baron. Rapeseed cultivation has an important place in his portfolio and Agrofert has become the most significant player in the Czech biofuel business.

Slovakia has committed to increasing the share of biocomponents in fuels from 8.2 to more than 11 percent by 2030. The European Union has several funds and financial instruments to support biofuels. Some Member States favor them through subsidies or tax breaks.

Between 2014 and 2020, the EU spent around 370 million euros on biofuels-related research. However, according to a report published last year by the European Court of Auditors, despite this support, biofuels policy is inconsistent and unclear — a reality that may also jeopardize the objective of reducing transport emissions.

Why has rapeseed taken hold of the fields?

What we put in our cars directly affects Slovak agriculture. Yellow oilseed rape fields provoke passionate reactions every year and not without reason: They have displaced more traditional crops and food production. In the fields, they have expanded thanks to the addition of biofuels to petrol and diesel. Rapeseed is also grown by the biofuel producers themselves, who thus control the whole chain of production.

However, bio-components, for years regarded as a solution to the climate crisis, are also increasingly the subject of criticism — particularly the first generation of biofuels, produced from agricultural crops, which is dominant in Slovakia and accounted for 100 per cent of all biofuels until 2021, despite the EU’s limiting measures and recommendations.

The EU has already adopted measures limiting first-generation biofuels. Today, about 95 percent of biofuels in Slovakia come from agricultural crops. Advanced biofuels from used oil and similar products, which should be the solution to the situation, have so far made only minimal inroads in Slovakia.

In the case of Ján Sabol’s ENVIEN group and its biofuel business, the main raw materials are rapeseed and corn, which is why their main product is first-generation biofuels.

The business starts with the farmers and ends at the gas stations. This trend is also supported by large farms that benefit from subsidies. Michal Wiezik, MEP and ecologist, argues that biofuel policy no longer contributes to climate protection: “It fundamentally damages the environment, it distorts the market and it is basically one big greenwashing.” Dusan Drabik, an expert on agricultural economics, adds that “biofuels have contributed to the rise in food prices,” but acknowledges that the EU does not have many alternatives.

Rapeseed is profitable for farmers, but it is also often environmentally problematic due to the use of chemical products, according to experts. Growers do not see a problem. The Chamber of Agriculture says rapeseed has an irreplaceable place in Slovak soil: “It has a significant anti-erosion effect, it stays in the field for 10 to 11 months, it has a rich root system, it is a source of organic mass for the soil.”

The Sea of Rapeseed. Source: ICJK

Opinions also differ between ministries. While the Ministry of Agriculture claims that rapeseed has positive effects on the soil, the Ministry of the Environment warns of the ecological problems associated with big monoculture, which is problematic for the Slovak land’s biodiversity, and the chemical treatment of rapeseed.

Why biofuels?

Biofuels have become a key part of the European Union’s energy policy and are considered an important tool for meeting climate targets. They were intended to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transport. Biofuels are blended into both petrol and diesel. Ethanol is used as an additive for petrol engines and biodiesel for diesel engines. According to the Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute (SHMU) data from 2022, “more than 220 million liters of biofuel were introduced to the Slovak market, of which more than 71 million were bioethanol in petrol and more than 167 million were biodiesel in diesel.” The largest sources of biofuels were rapeseed and corn.

More than half of the country’s biodiesel is made from rapeseed. And most of the rapeseed grown in Slovakia goes to biofuel production. In 2021, 94.3 percent of rapeseed grown in Slovakia went to biofuels; a year later, the number dropped slightly, but was still at over 80 percent.

That is why rapeseed is also dominant among oilseeds in Slovakia. The Ministry of Agriculture explained that it is a popular commodity due to high market demand and favorable prices. According to experts, it is the Union’s biofuel policy that has contributed to rapeseed cultivation being considered economically viable.

Michal Wiezik thinks that the EU’s biofuel policy initially seemed like a good idea but ended up as a serious problem. Agricultural economics expert Dusan Drabik also sees biofuels as being responsible for the rise in food prices. Nevertheless, he warns that the EU must do something. “I don’t know if we have other alternatives yet. We also have to realize that it is nice to have renewable electricity, but if we don’t have cars that can use it, it is hard to reduce emissions.”

For EU targets, we are relying on biofuels — but the wrong kind

Bio-based components have been added to fuels in Slovakia for almost 20 years. In 2006, the national mandate was such that they made up 2 percent of fuel.

In 2022, that percentage was increased to 8.6 percent. The plan for a gradual increase to 11.4 percent by 2030 was part of an amendment to the Renewable Energy Sources Promotion Act prepared by former Slovak Prime Minister Eduard Heger’s government. The amendment was also one of the milestones of the Recovery Plan for the third payment of €815 million.

The Ministry of Economy argued that the increase in the mandatory share of the biocomponent is necessary to fulfill the objective of using renewable energy sources for transport. The ministry admitted that the state is relying on older methods, especially the blending of biofuels into motor fuels, which is expected to reach the set target in 2030. Moreover, in 2020, biofuels accounted for more than 90 percent of all renewable energy in transport in the country and, according to the ministry, “are today irreplaceable by other technologies.”

However, the type of biofuel used is also important. According to Eurostat data, biofuels together account for more than 89 percent of renewable energy sources in transport in the EU. Of these, a significant portion is first-generation, i.e. produced from crop sources.

Their effectiveness and especially their sustainability, though, have been debated for several years. The European Commission, for example, recognizes the role of biofuels produced from crops, but is pushing for legislation to gradually restrict their use. Proponents of this change say they are concerned about the impact on the environment and food security. This is because first-generation biofuels also compete with the food processing of agricultural crops. Their use is also associated with a high risk of so-called indirect land-use change, according to the advocates of the restriction. According to the German Ministry for the Environment, their benefits are overestimated. The Swedish government sees it similarly.

But Slovakia is not following this trend or making this change. According to the Ministry of Economy, up until 2021, all blended biocomponents in Slovakia were first-generation. The situation has not changed significantly in the following years either. Last year, first-generation biofuels still accounted for 93.9 percent of all biofuels placed on the Slovak market.

The share of first-generation biofuels should not exceed 6 percent of the total volume of fuels used in transport. A Slovak law from 2023 also says that biofuels produced from food and feed crops are to be counted only “up to 6 percent of the total energy content of diesel and petrol placed on the market.”

The remainder would be made up by so-called advanced biofuels and biofuels made from used cooking oil (up to a maximum of 1.76 percent). How will the state support the development of the use of second-generation biofuels in Slovakia? By setting compulsory, gradually increasing minimum blending ratios, says the answer of the Ministry of Economy.

Another important issue is the impact of agricultural crop use on biodiversity, water resources, water quality and soil quality. We have sought further information on the impact in these areas from the Ministry of the Environment but were told that “they do not have relevant data on negative impacts.”

Rapeseed and biofuels

Rapeseed is an important raw material for the production of biodiesel. According to Dusan Drabik, an expert in agricultural economics and rural policy at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, there is a link between the state’s policy on biofuels and what is grown in Slovakia. In 2007, a government document stated that 100 thousand hectares of arable land had to be allocated to growing rapeseed for the production of biofuels.

In 2020, Dušan Drábik and his colleague Ján Pokrivčák pointed out that “mandatory quotas for the share of biofuels have triggered the emergence of a biofuel vertical in Slovakia, but also in Hungary or the Czech Republic, from rapeseed and maize growers to processors, refineries and petrol stations.”

Demand has created favorable economic conditions for the cultivation of these crops. “In a market environment (in the case of no regulation), the market decides what is grown and how much is grown through price,” explains Drabik. However, he adds that Slovakia is a small country economically, and so does not influence the price of rapeseed on world markets.

Viera Petlušová, an expert on ecological soil conditions from the University of Constantine the Philosopher in Nitra, also points to the economic dimension of this issue. “Rapeseed has a wide economic significance, as it is an essential part of crop rotation and an important source of economic income for farmers.” However, she says, the intensity of its cultivation can have a negative impact on the soil and other environmental components.

The Ministry of Agriculture is positive about rapeseed cultivation. According to them, it has a positive effect on the soil structure, its water and air regime and the increase in organic matter content. They also say that it increases soil fertility. The Ministry of the Environment, on the other hand, talks about the negatives. They say the huge swathes of rapeseed monocultures are extremely problematic in terms of their impact on the state of nature and the landscape, as these crops are regularly sprayed and fertilized on a massive scale with a range of approved chemical products, leading to the elimination of other species in the treated area. “The result is large ecologically unstable areas of such crops,” adds the department.

How much rapeseed is too much?

According to statistics, rapeseed has gradually become one of the dominant crops in Slovak fields. At the moment, its cultivation area has stabilized at around 145 thousand hectares. The significant increase in the area under cultivation began at the turn of the millennium. According to data from the Agricultural Payments Agency and our own calculations, over EUR 12 million in direct payments were paid out for rapeseed cultivation last year.

One of the defenders of rapeseed in our country is the Slovak Chamber of Agriculture and Food. According to them, Slovakia shouldn’t be thought of as one of the countries that grows a lot of rapeseed, despite the fact that Slovakia lies in the so-called rapeseed area.

But they are referring to absolute acreage. And if we look at the proportion of rapeseed in Slovak fields, it ranks in the top five in the European Union. The neighboring Czech Republic is in first place. In some years, Slovakia has even been in second place behind its western neighbor.

According to agricultural economics expert Drabik, it is meaningless to compare absolute acreages. It is more important to compare the proportional representation of rapeseed. In this respect, Slovakia ranks at the top of the EU. However, it must not be forgotten that the differences also depend on the suitable agro-climatic conditions for growing rapeseed.

Rapeseed is mainly found in the south

Slovak soil is ideal for growing rapeseed. Most rapeseed can be found in the south of the country, and particularly in the Nitra region.

On Rye Island sits the Sokolce Agricultural Cooperative, which, in 2022, grew the plant in an area of more than 500 hectares. “We came to growing rape on the Rye Island out of a certain necessity, which was triggered by a change in the structure of production on those individual farms and entities,” cooperative’s chairman, Peter Lelkes, explains to us.

According to Lelkes, rapeseed had no place in the region in the previous millennium, and cultivation only started around 2000. “We started with around 100 to 150 hectares and now we are growing oilseed rape on over 600 to 700 hectares.” He sees no disadvantages to the crop. “In terms of how to maintain soil fertility and as a pre-crop, oilseed rape is one of the best crops. It works that root system through the soil in such a natural way that even a plough or some other tool can’t do it any better.” He also doesn’t think it should be considered a monoculture “in that production structure it looks as if it was just somehow designed to be a monoculture, but it never was, because you can’t grow rapeseed in a row,” explains the farmer.

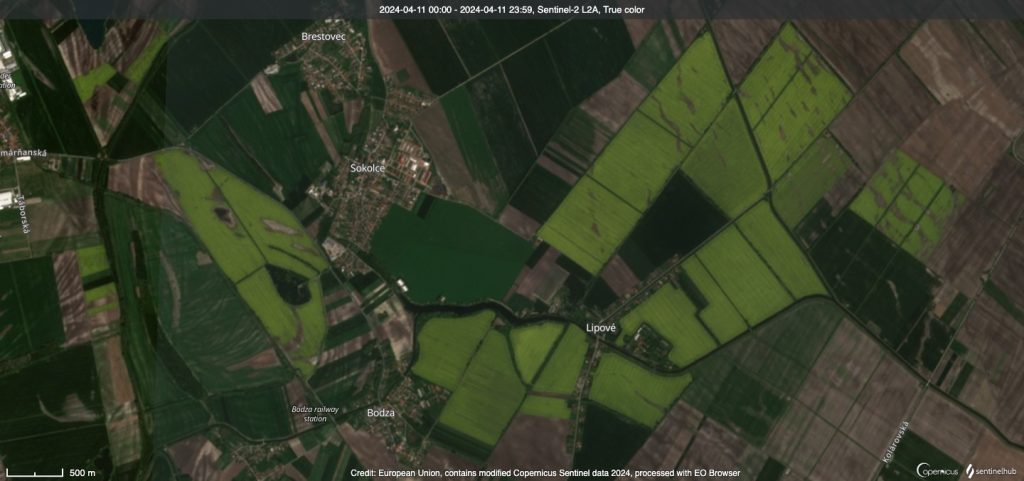

Rapeseed around the village of Sokolce in satellite images. Source: Sentinel

A common argument often raised in relation to rapeseed cultivation is that there are no quotas and farmers are in no way limited in what they grow on their land. According to southern Slovak farmer Michal Roháč, a regenerative farmer, the “rapeseed” formula is much more complex. “Nobody is forcing them, that’s true,” he concedes. But, he says, they are effectively forced by the agricultural subsidy scheme for commodity cultivation. “We are talking about large farmers who farm hundreds to 1,000 hectares, who receive a subsidy depending on the area they farm,” he explains. The result, according to Roháč, is a monoculture. “Whether it’s maize or rape, and I think that’s the worst thing that can exist,” he adds.

Experts pointed out years ago that direct payments combined with large acreage creates a very good business model for large agribusiness players, which also provides them with a solid return on capital. Drabik and Pokrivčák also add that “large farms benefit from economies of scale, which are best applied to cereals and oilseeds, less so to fruit and vegetable production or cattle farming,” which also gets to the point that it is not the plant itself that is the problem, but rather the amount of land sown for and dedicated to it.

Who makes money from biofuels?

Biofuels also bring profits to the Envien group of Slovak businessman Ján Sabol and his partners. He is one of the strongest biofuel producers in Europe — so much so that he is nicknamed the king of biofuels. Envien’s success is due to a long-standing partnership with Hungarian refining giant MOL and its Slovak refinery, Slovnaft. Sabol’s long-time business partner, a close friend of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, is Oszkár Világi, who is also the CEO of Slovnaft. Világi has worked at MOL for many years.

The ever-growing biofuel business has enabled the Sabols to build Envien, their Central European biofuel empire. The core of the group consisted of Slovak companies linked to the group around Sabol: bioethanol producer Enviral, biodiesel producer Meroco and commodity trader Enagro. The biofuel production center was built near Leopoldov in close proximity to the Slovak distilleries which also belong to the Sabols.

Its construction was also paid for by subsidies from the Agricultural Payments Agency. The group gradually expanded to other countries: First to Hungary, and later to the Czech Republic, Croatia, Poland and Switzerland. At the same time, it acquired influential business partners: the Hungarian oil and gas giant MOL, the Bratislava-based Slovnaft refinery and Agrofert, owned by former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, nicknamed the “Yellow Baron.”

However, it is not only the biofuels business that links the aforementioned Sabol group and the head of Slovnaft, Világi. Their names are also linked to Exata Group: Based on findings from the register of public sector partners, the Exata Group has a stake in 15 agricultural cooperatives, companies or firms in Slovakia, and on their website they write that they currently associate 27 farms across Slovakia. Companies belonging to the Exata Group are also involved in rapeseed growing.

The article was written as part of the Bertha Challenge 2024 project dedicated to tackling environmental disinformation. The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

The article was written as part of the Bertha Challenge 2024 project dedicated to tackling environmental disinformation. The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

Karin Kőváry Sólymos is a Slovak journalist at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak. Previously, she was an editor and presenter at the Hungarian channel of the Slovak public service media. During her university years, she was an analyst for the only fact-checking portal in Slovakia. She was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.