OSINT research: Alicja Pawłowska,

Visualisation: Anastasiia Morozova 2025-01-17

OSINT research: Alicja Pawłowska,

Visualisation: Anastasiia Morozova 2025-01-17

Stanislaw Szypowski, convicted for spying for Russia’s military intelligence (GRU), stole a classified report on an LNG terminal, helped select informants for recruitment, and promoted pro-Russian narratives in Polish media. After seven years in prison, he re-emerged as a businessman attending numerous events, including embassy gatherings and conferences on Ukraine and FinTech, meeting regularly with state officials, without intelligence services raising alarms. His current activities resemble his pre-arrest GRU operations.

From the windows of the Rotunda PKO BP, a circular office building in central Warsaw, one can see the Palace of Culture and the city skyline. Afternoon conferences for the elite of the business community are often held here.

In early December, leaders of the FinTech industry—companies focused on innovative financial technologies—gathered at the Rotunda. Among them was Stanislaw Szypowski, a lawyer with a history of espionage, who lingered in the background of the conference.

The event began with expert panels, while dozens of attendees listened in anticipation of the evening cocktail. Szypowski, after taking a few photos, retreated to the back of the room, where he engaged in animated conversations. He spent four hours backstage, speaking primarily in Russian—a language he grew up with, having spent the first five years of his life in Russia before moving to Poland with his family.

Russia has played a significant role in Szypowski’s life: he spied for the Russian Federation for nearly three years until October 2014, when Poland’s Internal Security Agency (ABW) arrested him.

After serving seven years in prison, Szypowski did not move to Russia or change his profession. Instead, he established a company offering legal advice.

We have found that he frequently attends events with politicians, diplomats, and businessmen, including those from beyond Poland’s eastern border. He moves freely in and out of embassies, ministries, and government offices and has even begun organizing his own events.

His earlier focus was on energy. Now, it’s logistics, state tenders, and the reconstruction of Ukraine.

Figures like Szypowski pose a challenge for intelligence services and the state: How should the activities of a former spy in the public sphere be addressed? This is especially pressing today, as Russia’s actions in Poland are no longer limited to floods of trolls on the social media platform X but include provocations, sabotage, and physical attacks on factories.

Stanisław Szypowski establishes contacts at a recent conference in Rotunda, photo by FRONTSTORY.PL

“Exceptional intensity of ill-will”

In mid-October 2014, masked ABW officers arrested Szypowski, who was then working as a lawyer for a Warsaw law firm. At the prosecutor’s office, he was charged with espionage for Russian military intelligence (GRU).

In photos from the courtyard of the Warsaw District Court, it’s hard to recognize the man who would reappear a decade later at the Rotunda. In 2014, he was stocky; today, he is slim, balding, has changed his glasses, and proudly promotes his healthy lifestyle. Remarkably, he looks younger now than he did ten years ago.

Stanisław Szypowski during his arrest in 2014, photo by Agencja Reporter.

When Szypowski was detained, security officers seized a notebook and memory cards from his apartment, uncovering material he had collected for the Russians. Among the data were profiles of journalists, PR specialists, and experts, all selected by Szypowski for potential recruitment by the GRU.

In 2017, a court sentenced him to four years in prison for collaborating with Russian intelligence. On appeal, the sentence was increased to seven years, with the court citing Szypowski’s “exceptional intensity of ill-will, premeditation, and disregard for legal and ethical norms.”

During the hearings, it was revealed that Szypowski, acting on GRU instructions, gained access to a classified Supreme Audit Office (NIK) report on the Świnoujście gas terminal, including unofficial information about the construction’s completion date. He collaborated with politicians, experts, and journalists in the energy sector, identifying those potentially vulnerable to Russian influence. He also facilitated the publication of articles promoting Russia’s perspective on energy issues.

Both courts unequivocally concluded that Szypowski had knowingly collaborated with Russian intelligence and deliberately acted to the detriment of Poland.

Stanisław Szypowski during his arrest in 2014, photo by Reporter Agency.

Although the ABW gathered evidence of Szypowski’s contacts with GRU officers and reports he had written for them, he denied his guilt. He argued there was no proof that the Russian diplomats he met were GRU agents and claimed his interactions with them were purely social (a claim the appellate court dismissed as naïve).

According to the ABW, when one of Szypowski’s GRU handlers left Poland, he was subsequently taken over by another officer.

After his release from prison in 2021, his father, Sergei—former goalkeeper of Pogoń Szczecin and a well-known soccer coach—spoke about his son in an interview with Przegląd Sportowy: “They didn’t prove anything against him, but they locked him up. I am proud of him because he has character and didn’t let them break him.”

“I was managed by a Russian spy!”

Shortly after his release from prison, Szypowski applied to UnityHub Lawyers, a law firm serving business clients from Ukraine and former Eastern Bloc countries. He was initially rejected but reapplied six months later and was successful. In May 2022, he became an account manager, acting as a liaison between the legal team and clients. How did he explain his seven-year employment gap to his new employer?

“He had a talent for networking and a natural ease in conversation. That’s what convinced me. He didn’t mention the seven-year break,” says Wiktoria Kosmyna, CEO of UnityHub Lawyers. “He proposed a B2B contract as a form of collaboration. When hiring full-time employees, I usually request a certificate of no criminal record. It didn’t occur to me that this was the reason behind it, not the lower social tax contributions. After this experience, we revised our recruitment procedures to prevent such situations.”

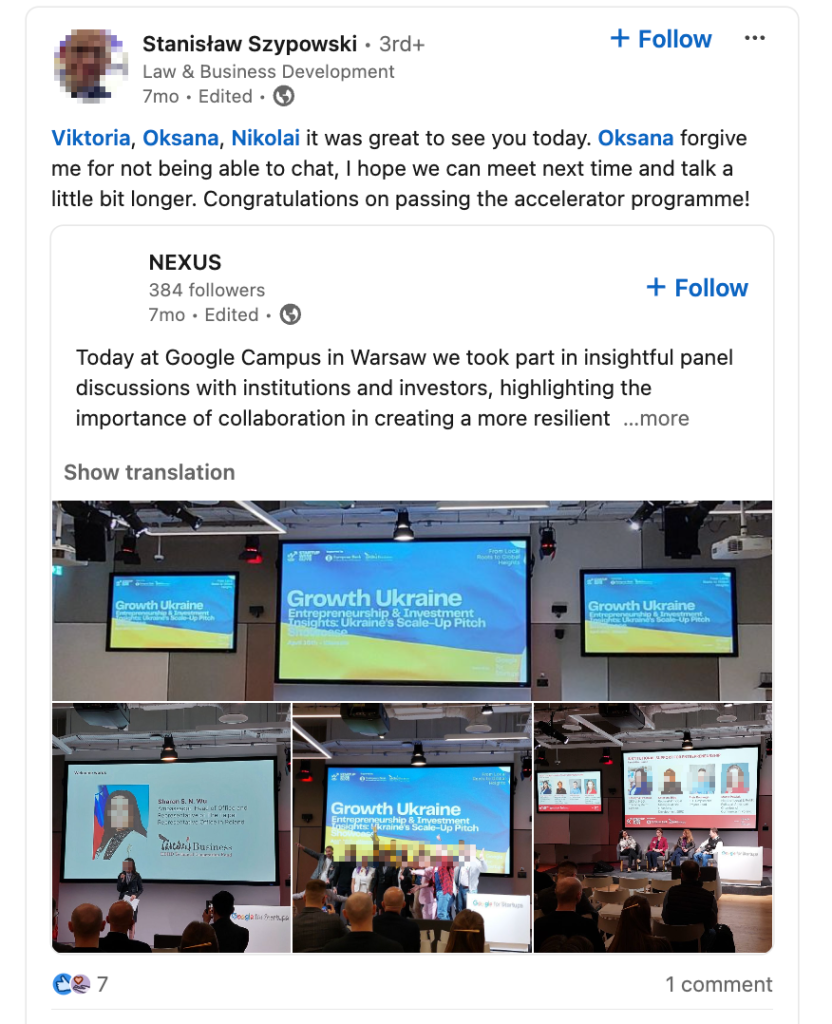

Szypowski’s role involved client acquisition, which in practice meant attending conferences, training sessions, and networking events. He appears in photos from meetings with the Ukrainian Business Women Club and a construction industry forum focused on Ukraine’s reconstruction. According to Kosmyna: “He is a master networker and an excellent event organizer. He could attend events seven days a week and come back with a stack of business cards from just one day of socializing.”

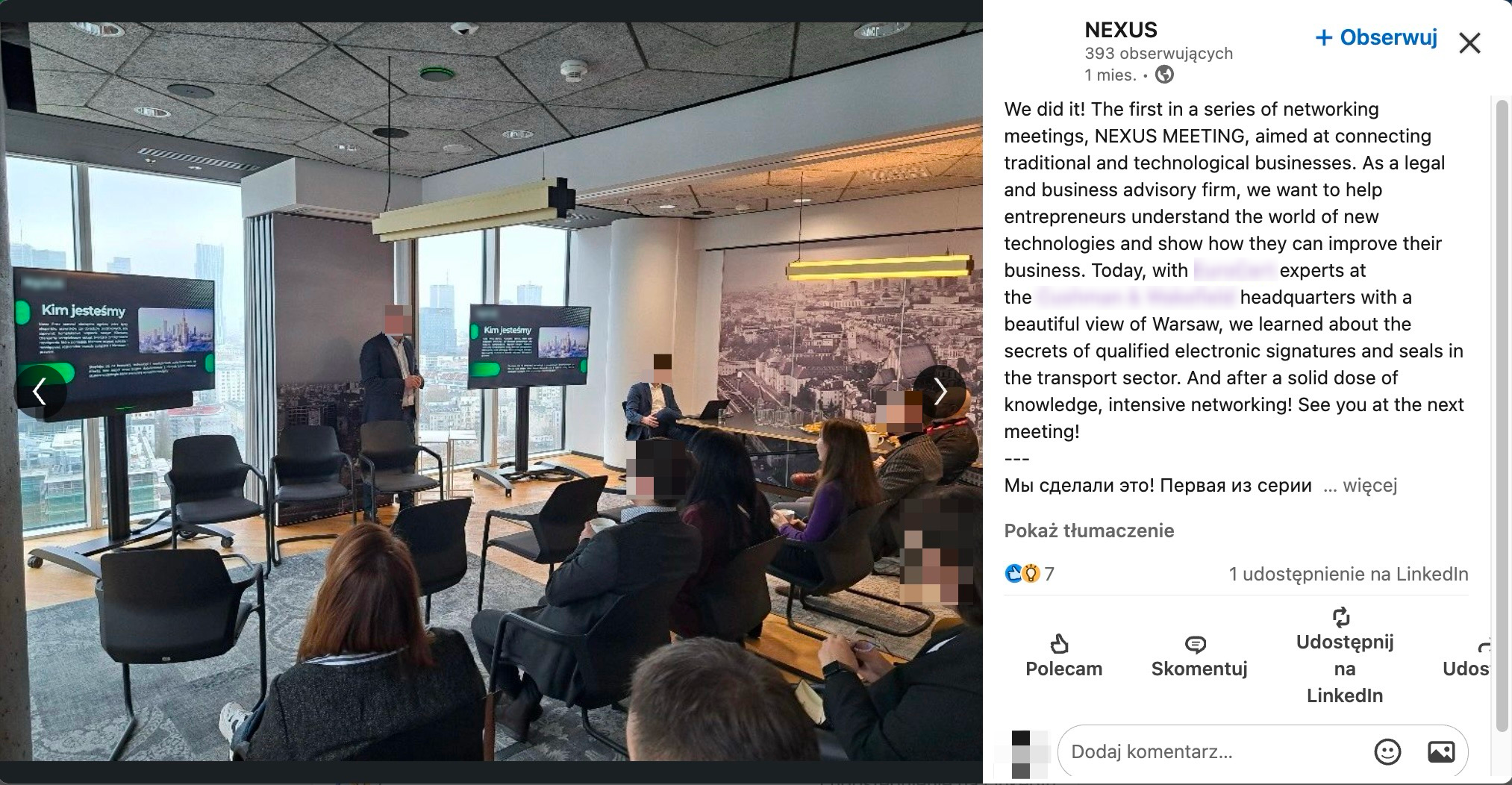

Nexus and Stanisław Szypowski’s social media post from a recent conference

In September 2023, after several months of collaboration, Kosmyna fired Szypowski for inefficiency, as he failed to convert contacts into signed contracts. Kosmyna says she only discovered his past as a spy later. By chance, an employee encountered an old acquaintance of Szypowski’s, who revealed the espionage case. “She was shaken—she realized she was being managed by a Russian spy! And this in our company, which had cut ties with Russian firms immediately after the invasion,” says Kosmyna.

“Conferences are a goldmine for acquiring information”

In October 2022, Szypowski registered his own consulting company, Nexus, where his father is also a partner. (The company reported minimal revenue and profit in 2023.) He remains very active on LinkedIn.

We analyzed Szypowski’s posts, comments, and reactions on his personal and company accounts. His activity is remarkable. Between May 2023 and December 2024, he attended 98 events, including conferences, panel discussions, and business meetings, mostly in Warsaw.

The events primarily focused on Ukraine’s reconstruction, business in Central Asia, and new technologies in finance and logistics. They were organized by groups such as the Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, the Polish-Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce, the Belarus Business Center, the Polish Investment and Trade Agency, the Ministry of Development and Technology, and the Patent Office. Szypowski also visited embassies of countries including Uzbekistan, Lithuania, Estonia, France, Belgium, and the UK.

We contacted over 30 event organizers to ask whether Szypowski had been invited and whether guest identities were verified. Responses revealed that he mainly attends free, open-admission events. Few institutions noticed him, with the exception of the Polish Investment and Trade Agency, which claims to have identified him in January 2023. “Information on this matter was immediately forwarded to the relevant services,” the agency stated.

We spoke with six individuals who had met Szypowski at events. None knew they were interacting with a former GRU spy. “I had no idea,” wrote one lawyer who met him at a Polish-Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce event. He described Szypowski as friendly and approachable—the type of person you’d go out for a beer with.

Attorney Robert Nogacki, founder and partner of Skarbiec Law Firm and co-author of Security of a Modern Company, explained the intelligence value of such events: “Conferences are a goldmine for acquiring information. Logistics and certified signatures in logistics are key for bypassing sanctions. FinTech involves cryptocurrencies, which are also used to circumvent sanctions. And start-ups and new technologies attract the most influential minds in the country. From Russia’s perspective, access to these individuals is invaluable.”

Coffee and cake with the minister?

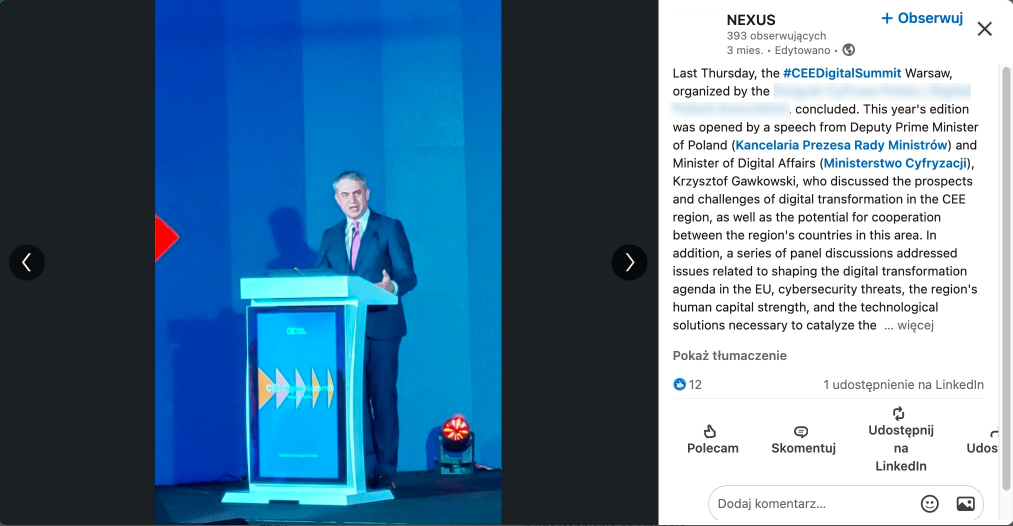

Among the speakers at conferences that Szypowski posted about on LinkedIn were Deputy Prime Ministers Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz and Krzysztof Gawkowski, Development Minister Krzysztof Paszyk, the president of the Warsaw Stock Exchange, the president of the Polish-Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce, and representatives from the Heritage Foundation, a think tank known for its support of Donald Trump.

High-ranking officials and leaders of state-owned companies—such as Deputy Foreign Ministers Marek Prawda and Andrzej Szejna, Deputy Infrastructure Minister Piotr Malepszak, the government plenipotentiary for the construction of CPK Maciej Lasek, and the head of PKP PLK—regularly attend events where Szypowski is present.

Polish intelligence services have not issued any warnings to officials or entrepreneurs about meeting with Szypowski.

Nexus and Stanisław Szypowski boast a photo on social media from a conference attended by Poland’s deputy prime minister

We asked Deputy Prime Minister Krzysztof Gawkowski how the events he attends are vetted. “Such events are usually related to the ministry’s areas of work. The subject matter and the organizer are reviewed, but it’s impossible to check the hundreds or thousands of participants who register or attend, especially at open events,” he explained.

A similar response came from the Ministry of Defense. “We vet the event itself, including the organizer, and the services assess the level of physical security, such as pyrotechnic measures. However, we have no control over who might attend the Deputy Prime Minister’s speech,” said Janusz Sejmej, the ministry’s spokesman.

According to sources familiar with the protocols, ministers under Donald Tusk’s government received clear guidance early in their tenure: they were to appear only for keynote speeches and leave conferences promptly, avoiding behind-the-scenes mingling or banquets.

Recently, Szypowski even organized his own conference on qualified electronic signatures in the transport industry.

For Russia, “I would like to do something more”

Szypowski’s trial was held in secret, and journalists still have no access to his case file. So how do we know what Szypowski did for the GRU?

A detailed description of his activities is included in the publicly available justification of the Warsaw court’s verdict. Although the court denies access to the full documents, it published the public portion of the verdict online five years ago.

While the names were anonymized, we managed to identify some of them.

A reconstruction of the Szypowski case, based on the verdict, might look like this: In 2008, at 22 years old, he wrote an email to Putin’s United Russia party (of which he was a member). He boasted about promoting Russia’s perspective to his fellow students but expressed a desire to do more. “I would like to do something more,” he declared. He also unsuccessfully sought internships at Russian companies, including Lukoil, and the Russian mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva.

How he ultimately came into contact with the GRU remains unclear. According to the ABW, Szypowski began spying for the Russians by early 2012. He attended meetings with Russian intelligence officers, received training, and began his espionage activities.

At the time, he worked at a law firm in Szczecin, handling construction for the breakwater at the Świnoujście LNG terminal—a key investment for Poland’s energy security. The terminal receives liquefied gas, including from the US, enabling Poland to wean itself off Russian gas after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

Szypowski’s activity increased in 2014, a pivotal year when Russia annexed Crimea and started the war in eastern Ukraine. The ABW summarized Russian actions in 2014: “The activities of these services (…) were aligned with the Kremlin’s propaganda strategy. They aimed, among other things, at discrediting the positions of Poland and other NATO member states on the Ukrainian crisis and at emphasizing the complex Polish-Ukrainian historical experience to provoke antagonism (…).”

The ABW also noted an “intensified effort by various Russian institutions to consolidate and activate (…) pro-Russian circles.”

Russia’s focus on energy intersected with Szypowski’s espionage. He provided the GRU with a classified Supreme Audit Office (NIK) report on gas contracts and the Świnoujście terminal. He even gained access to the Sejm during a session of the extraordinary committee on energy and energy resources, where he recruited two individuals (their identities remain unknown). These recruits unknowingly worked for him, preparing reports on the meetings at a rate of PLN 5,000 (€1,200 at current rates) per report, unaware they were aiding a Russian spy.

The breakwater in Świnoujście, where Szypowski was involved in the construction. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

How could someone like Szypowski gain access to the Sejm? According to TVN24.pl, he was invited by the Palikot Movement club. We investigated: the only “Palikot” member of the committee at the time was Jacek Najder (who left the Sejm in 2015).

In an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL, Najder denies inviting Szypowski. However, he recalls that around that time, a lawyer offered to assist him in drafting energy legislation. Najder requested that the proposal be sent via email, and the contact ended there.

From “Biznesalert” to “Krytyka”

Szypowski was also quietly engaged in propaganda activities. An example? He facilitated the publication of an article aligned with the Kremlin’s narrative to undermine Poland’s energy policies. He contacted Konrad Rękas, deputy head of the pro-Russian Zmiana party (whose leader, Mateusz Piskorski, was later accused of spying for Russia and China and is still on trial). Szypowski proposed that Rękas write a quick piece on the energy policy consequences of the Ukrainian crisis. Rękas agreed, and his column, titled “Ukrainian Rhinitis – Polish Flu,” was published in June 2014 on biznesalert.pl. A reprint of the article remains available on conservatism.pl.

Judge Agnieszka Domańska, who sentenced Szypowski in the GRU espionage case, summarized Rękas’ piece: “It is a superficial and one-sided analysis of Poland’s energy policy, ultimately advocating that the best solution to Poland’s gas supply issues would involve the realization of the Yamal-II project [a second gas pipeline from Russia through Poland], joining the Nord Stream project [a gas pipeline connecting Russia and Germany under the Baltic Sea], abandoning the Common Energy Policy, and ceasing work on shale gas imports.”

Konrad Rękas told FRONTSTORY.PL that Szypowski had no involvement in the creation of the text, claiming its content remains valid. Rękas is now active in the All-Poland Trade Union Alliance of Farmers and Agricultural Organizations, which shares blog posts from him on its Facebook page warning of unfair competition from Ukraine.

Szypowski also published his own articles on Polish-Russian relations in prestigious media outlets such as Krytyka Polityczna, Tygodnik Powszechny, and Nowa Europa Wschodnia. These writings were not radical or propagandistic but aimed to establish Szypowski’s image as an expert.

“It’s mainly about training, trips to regions, personal contacts”

The court described how Szypowski “leveraged his employment at law firms, his doctoral research on energy law, his firm’s membership in the Gas Industry Chamber of Commerce, and his participation in conferences and industry training in the energy sector to carry out active intelligence activities, through which he obtained information and identified potential targets.”

Szypowski benefited from his position. At the law firm where he worked, he handled cases for ministries such as finance, regional development, sport, and tourism, as well as the state-owned PKP PLK SA. His role as a lawyer provided opportunities to network: he attended conferences, gathered insider information, observed attendees, and identified potential GRU collaborators.

In his CV, written after his release from prison, Szypowski notes that in 2013-2014 (during his time spying for the GRU), he worked with companies from Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. In a 2014 recording, he spoke about shifting entrepreneurs’ approaches to investing in Belarus, saying: “It’s mainly about training, trips to regions, personal contacts, discussions, and sharing experiences.”

In his reports for the GRU, Szypowski included profiles of journalists and energy industry experts, assessing their susceptibility to Russian influence and the potential to manipulate them through disinformation campaigns. Among others, he focused on journalists from the Polish Press Agency covering energy issues. He also hinted to his handlers that Grzegorz Hajdarowicz, owner of the company publishing dailies such as Rzeczpospolita and Parkiet and the weekly Uważam Rze, might be willing to sell his shares.

At the end of 2012, Szypowski registered with the West Pomeranian Association of Russians in Szczecin, where he still serves as chairman of the main board. The contact email for the organization remains Szypowski’s personal address.

While actively spying for the GRU, Szypowski applied for Polish citizenship, which he was granted in 2013. After his arrest, the President’s Office explained that both the Interior Ministry and the ABW had given favorable opinions of his application, leaving no grounds for denial.

However, statements by then-Minister of Internal Affairs Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz suggest that granting citizenship to an active spy may have been part of a broader operation by Polish intelligence services. We sought to ask Sienkiewicz about this, but he did not respond to our interview request.

Eye on the spy

How is it possible that a former Russian spy, after serving his prison sentence, could establish a company advising Ukrainian businessmen as if his arrest for espionage never happened?

The law allows it. The Commercial Companies Code prohibits individuals convicted of certain crimes from representing companies—but espionage is not among them. For example, someone convicted of forging signatures or disclosing confidential information cannot serve as a company’s president or a member of its supervisory board. Yet, despite Szypowski handing over a classified NIK report to the Russians, these restrictions do not apply to him.

Experts we spoke with argue that changing the law for cases like Szypowski’s is unnecessary. “Article 41 of the Criminal Code allows a court to impose a ban on conducting certain business activities or holding specific positions if the individual abused their role in committing the crime or poses a continued threat to legally protected interests,” attorney Nogacki explained in an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL.

We checked: the judge who sentenced Szypowski chose not to invoke this option. As a result, even though Szypowski’s espionage conviction will not be expunged until 2031, there are no legal restrictions on his business activities.

“There are no legal instruments to prevent someone from starting anew after serving their sentence,” said General Janusz Nosek, former head of the Military Counterintelligence Service and now an expert with the Parliamentary Commission for Special Services, in an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL. “However, this doesn’t mean the state should forget about him. Poland should ensure that such an individual remains under its watch.”

Szypowski posts from a conference on Ukraine’s development

According to Nogacki, it is the responsibility of the ABW to ensure that individuals posing a threat to state security are kept away from public institutions and key officials. Has the ABW fulfilled this duty in Szypowski’s case?

In response to our inquiries, the agency assured us that such threats are recognized and monitored. However, it declined to comment on specific cases.

In an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL, Szypowski claimed that no security services had shown any interest in him since his release from prison.

Double agent begins to fall apart

Szypowski’s detention in 2014 was part of a coordinated operation by military and civilian intelligence services. On the same day, Lieutenant Colonel Zbigniew Jedliński was also detained, with media attention primarily focused on him. The prosecutor general at the time, Andrzej Seremet, explained that while the cases of the military officer and the civilian were connected, the link was not through direct interaction.

So, what connects the stories of Lieutenant Colonel Jedliński and the civilian Szypowski? And how did the ABW come to target Szypowski? New details shed light on this decade-old case.

By 2014, military intelligence had been monitoring Zbigniew Jedliński, a lieutenant colonel from the Department of Defense Education and Promotion, for some time. They knew he was collaborating with the Russians in exchange for money, providing valuable information to the GRU, including data from the Ministry of Defense’s internal IT system (MILWAN) on over 100 officers, including chiefs of staff. As a result of these events, the MILWAN system was eventually shut down.

Before his detention, Jedliński agreed to cooperate with Polish counterintelligence. Under their control, he continued meeting with the Russians and even used a special cell phone provided by the GRU to contact officers and take photos. Through Jedliński’s cooperation, counterintelligence uncovered further leads, one of which pointed to Szypowski, a young lawyer working at a Warsaw law firm. Although Jedliński and Szypowski did not know each other, sources indicate they were connected through a GRU officer. This handler reportedly tried to secure a job at Szypowski’s law firm for a relative (military counterintelligence later handed Szypowski’s civilian case to the ABW).

We reached out to a former partner of Szypowski’s law firm. He referred us to another partner, who confirmed working with Szypowski but denied that the firm ever employed Jedliński or anyone recommended by Szypowski.

Zbigniew Jedliński, charged with collaborating with Russian intelligence and passing classified information, faced up to 15 years in prison but was sentenced to six years after voluntarily surrendering to authorities.

The Szypowski and Jedliński cases had a diplomatic fallout: in autumn 2014, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, now aware of the background of their GRU operations, expelled two Russian diplomats for espionage. While these diplomats moved on to new postings, their methods did not change.

Soon, their activities would draw headlines again—this time in southern Europe.

Shirokov, or Shishmakov

Among the GRU officers expelled from the Russian embassy in Warsaw was Edvard Shishmakov, the deputy military attaché. According to investigative journalists from Bellingcat, Lieutenant Colonel Jedliński provided Shishmakov with data on Polish servicemen, including details of their offenses, criminal cases, and disciplinary issues. Jedliński admitted earning €5,500 from this information for the GRU. Bellingcat also reported that Stanisław Szypowski operated as an agent under Shishmakov’s direction.

A few months after Jedliński’s sentencing, a secret meeting took place in Moscow. Aleksandar Sindjelić, leader of the Serbian Wolves—a radical paramilitary group and a veteran of the Donbas conflict on the separatist side—attended the meeting, having been invited by individuals identifying as “Russian nationalists.” These individuals, introducing themselves as Edvard Shirokov and Vladimir Popov, revealed their ties to Russian intelligence services. Shirokov facilitated Sindjelić’s travel to Moscow, even bypassing passport control.

During the meeting, the men proposed a plan to overthrow the Montenegrin government to prevent the country from joining NATO. They outlined the operation using blueprints of the Podgorica parliament building and handed Sindjelić €200,000 in cash. The failed coup attempt was detailed by Bellingcat and the independent Russian news site The Insider.

Edvard Shismakov in Poland, March 2014. Photo source: Bellingcat

How does this connect to the Szypowski and Jedliński cases? Edvard Shirokov, who orchestrated the coup attempt in Montenegro, was actually Edvard Shishmakov, the former deputy military attaché at the Russian embassy in Warsaw and one of the officers handling Polish spies.

Shishmakov graduated from the GRU academy for undercover intelligence officers. According to Bellingcat, his coursemates included Igor Kostyukov (first deputy head of the GRU) and Sergei Zapadayev (commander of the GRU unit pivotal in Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine).

In 2013, Shishmakov served as a naval military attaché at the Russian embassy in Warsaw. Notably, in January 2014, he participated in a meeting at the National Security Bureau (BBN)—a Polish-Russian expert roundtable on “transparency in military exercises.” His name is still listed in the Polish communiqué from the event, though the Russian report omits any mention of him.

After his expulsion from Warsaw, Shishmakov reappeared as Shirokov, with a new identity and passport, as uncovered by The Insider. He took charge of organizing the Montenegro coup. However, he continued to use the name Shishmakov when signing Western Union transfers for those involved in the operation.

Edvard Shismakov and Vladimir Popov, GRU agents involved in organizing the attempted coup in Montenegro. Photo source: The Insider

Former Polish ambassador to Podgorica, Irena Tatarzyńska, admitted in a 2017 interview with Balkan BIRN journalists: “For us [in Poland], it was a really unpleasant case. The deputy military attaché was declared persona non grata. But for the Polish state, this matter is now closed. (…) Now we’ve been informed that the same person was allegedly involved in the coup attempt.”

When asked whether it had tracked the fate of the diplomats expelled in 2014 or warned allies about their activities, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded before publication: the ministry has no information about the whereabouts of the expelled Russian diplomats after they left Poland. It also declined to disclose their names, citing customs under the Vienna Convention.

In 2019, Shishmakov was convicted in absentia by a court in Podgorica for creating a criminal organization, terrorism, and inciting actions against the constitution and security of Montenegro, including the attempted assassination of the prime minister.

In 2021, one of his former operatives, Stanisław Szypowski, was released from prison.

“Does the name Shishmakov say anything to you?” we asked Szypowski in November 2024 during small talk backstage at a FinTech industry conference in Warsaw’s Rotunda.

“It doesn’t tell me anything,” Szypowski replied, cutting us off and ending the conversation.

The initial version of the story contained information that Szypowski attended event in the Spanish embassy. The organizer of the event ambiguously described it, leaving space for this interpretation. This was corrected due to the information from the embassy itself.

The Polish version of this story was published on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Daniel Flis previously was on the investigative team of OKO.press and Gazeta Wyborcza. OCCRP Research Fellowship Program recipient. Participant in international investigative projects of the Reporters Foundation.

Anna Gielewska is co-founder and editor-in-chief of VSquare and co-founder of Polish investigative outlet FRONTSTORY.PL. She is also vice-chairwoman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). A journalist specializing in investigating organized disinformation and propaganda, Gielewska was the John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2019/20) and has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2015, 2021, 2022) and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Award (2021, 2023). She was the recipient of the Novinarska Cena in 2022.