Illustration: ICJK 2025-02-21

Illustration: ICJK 2025-02-21

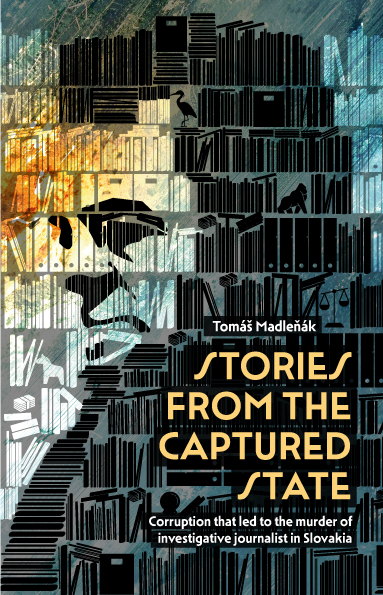

On Friday, February 21, 2025, we mark seven years since the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Even after all this time, the court case against those accused of ordering the killing remains unresolved. To honor Ján and Martina’s legacy, the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK), in partnership with Aktuality.sk, has published Stories from the Captured State (original Slovak title: Secrets of Kočner’s Library) — a book exploring the scandals uncovered through the murder investigation. Here, we share an excerpt from the book by ICJK reporter Tomáš Madleňák.

On Monday, February 26, 2018, I woke up in my parents’ house in Orava. Eyes half-open, I walked downstairs, brewed a cup of coffee, and sat down at the large dining room table. I opened my laptop. I had planned to work from home that day. At the time, I hadn’t even thought about journalism. I was working at the Slovak Foreign Policy Association. Since I’d gotten up late, it was time to at least open and check my email. Out of habit, however, I opened Facebook first. Immediately, my friends’ new profile pictures—black squares—started popping up on my timeline, and the name Ján Kuciak was mentioned, over and over again, in their statuses. I quickly clicked through several news websites. They all reported the same thing: A journalist had been murdered in Slovakia. As if in a haze, I walked from the kitchen to the living room, where my father was sipping coffee. When he saw me, he became alarmed.

“What happened?“

“They murdered a journalist.”

“Where?” He asked. Despite the fact that, unlike me, he lived through communism and was a fully conscious adult in the wild 90s, the period after the fall of communism marked by widespread crime and chaos, the threat of which I hadn’t perceived as a child, he wasn’t at all prepared that such a thing could happen anywhere nearby. As he told me later, he expected me to say Mexico or some African country.

“Here.”

“What do you mean here?“

“Well, here. In Slovakia.“

It had happened five days earlier, but it took four days before the family alarmed the police, concerned that the young couple did not return their calls. The police found the bodies on Sunday, and the public was informed on Monday. And it took even longer before we learned what exactly happened in Veľká Mača on February 21, 2018. At 16:40, former soldier Miroslav Marček met his cousin, ex-policeman Tomáš Szabó, and together they got into an old Citroën Berlingo. On the way, they switched off their mobile phones and turned on their work phones instead. They were simple Nokia and Alcatel push-button burner phones, meaning that the SIM cards were not linked to their names. Such phones are used just once, after which they have to be thrown away. You may have seen this in films, especially movies featuring criminals and crime stories, and they’re used the same way in reality. In really sensitive situations, we journalists also use them to protect the identity of our sources or to protect ourselves from eavesdropping and surveillance by the secret services. Especially in countries where there are no democratic governments and no rules, disposable phones have helped journalists in more than one situation. Marček and Szabó, however, had darker motives.

Please Be Available

Czech investigative journalist Pavla Holcová worked intensively with Ján Kuciak despite the fact that they were from different editorial offices and different countries. Ján worked at the online daily Aktuality.sk; Pavla is the founder of, and still runs, the Czech center for investigative journalism, Investigace.cz. Small non-profit centers, such as Investigace.cz and the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak, focusing on investigative journalism, are not uncommon. Compared to traditional newsrooms, they have advantages and disadvantages — the disadvantages being mainly a more limited reach and smaller readership. The advantage is that they do not compete with traditional media for revenue: advertisers aren’t interested, and, for many investigative outlets, putting content behind a paywall would be contrary to their mission. They mostly operate on small voluntary donations from readers and grants, like other NGOs. Therefore, traditional newsrooms don’t consider them competition and are often more willing to work with them. This culture of cooperation also extends internationally, and thus these centers are linked across borders. This was also the case for the Czech center, which is connected to several international organizations. Thanks to its membership in the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists ICIJ, in 2016, Pavla gained access to the momentous Panama Papers leak: a cache of documents from companies based in Panama that showed how these firms were being used to hide the assets of the rich and powerful[1] . Pavla brought in several journalists from both Czech Republic and Slovakia to work together to expose the scandals hidden in the documents. One of the journalists from Slovakia, Ján Kuciak, a young investigative reporter from Aktuality.

Pavla and Ján worked together for two years. Together they uncovered a mysterious shell company belonging to oligarch Miroslav Výboh. The company, hidden in the Seychelles, was also behind the ownership of part of the shares of the Bratislava DoubleTree by Hilton hotel[2] . Výboh is an oligarch and a friend of Robert Fico and was, at one point, considered a grey eminence behind Smer. In 2021 he was indicted for corruption[3] , but a change in the penal codein 2024 the statute of limitations of the case has expired. In the meantime, the oligarch settled in Dubai . [4]

Later, Pavla and Ján worked together on the topic of the Italian mafia in eastern Slovakia, uncovering a tragicomic love polygon that led all the way up to the prime minister Fico. However, this article was not published until after Ján’s death.

–

A year and a half after Ján and Martina were shot by a hired killer, Pavla was getting off a tram at the Charles Square stop in the center of Prague. A text message beeped on her cell phone: “Please be available.” Nothing more, just this one sentence from an unknown number — from Slovakia. She turned on the ringer so she wouldn’t miss the call, whatever it might be, and went to work. It was October 2019, and the trial of the people accused of Ján and Martina’s murders was due to start in a few weeks. After massive protests drove Robert Fico from the prime minister’s chair, Robert Kaliňák from the post of interior minister, and Tibor Gašpar from his position as police chief, investigators moved with shocking speed. Although the Italian lead was initially considered by many to be the most likely, the investigation led in a completely different direction.

Police and prosecutors identified Miroslav Marček, assisted by his cousin Tomáš Szabó, as the perpetrator of the murder. The order was believed to be received from their acquaintance, Zoltán Andruskó. He, in turn, was thought to have received instructions from Alena Zsuzsova, also from Komárno. These names were completely unknown to the public. On the face of it, there was nothing linking them to the murdered journalist and his fiancée. However, as the investigation showed, Alena Zsuzsová was a secret collaborator of one of the most controversial and influential men in the country: Marian Kočner. Ján Kuciak often wrote about him and his scams, and did it so well that it drove Kočner into a frenzy. So much so that Kočner called Ján on 5 September 2017 and started threatening him[5] :

Kočner: No, no, Mr. Kuciak. You are being very biased, you are one bad person who is being tasked by somebody, and believe me, I will find out who is tasking you.

Kuciak: You’re not right.

Kočner: I am, I am, I am. Just like you’re not right about anything, you know, I think I am. But you can be sure that I’m going to start paying special attention to you personally, Mr. Kuciak.

Kuciak: Is that a threat?

Kočner: Why? I’m telling you calmly. I’m going to start paying special attention to you and your person, your mother, your father and your siblings.

Kuciak: Do you know who involves the family in such disputes?

Kočner: Oh, go fuck yourself with your opinions, please! You’re dragging my family into this stuff too and you don’t even know it, and I’ll tell you one thing.

Kuciak: I’m not doing this on purpose.

Kočner: As soon as I find some dirt, some misdemeanours of yours, of your whole family, once again, some dirt, misdemeanours, crimes of yours and your family, everybody has something, rest assured that I will also publish it as you did, but also with evidence, not without evidence, just with evidence, so I will look for it, Mr Kuciak. You will be the first to be published on my website, I will dedicate a special place to you as the first journalist. If you are decent and honest, you will not be there, but I do not think so.

Kuciak: I hope I won’t be there.

Kočner: Goodbye. Believe that you will be.

As the investigation proved, Marian Kočner was indeed trying to find dirt on the young journalist. At least, that is how he explained why he sent a squad of spies to track him, led by Peter Tóth — a former journalist turned member of the Slovak secret service SIS who then becameKočner’s man for illegal surveillance. The explanation was essentially that this surveillance was already set up to document Kuciak’s movements, daily habits, routines and other details. What we now know for sure is that this later served the killers.

When Pavla Holcová arrived at work, she left her mobile phone with a ringer on, which is not typical for her. Otherwise, however, she did not think about the strange text message. For two hours she was not thinking about Kočner, his spies, hired killers, or about the Slovak politicians and businessmen ensnared in his networks. Then her phone rang and changed everything.

–

Drew Sullivan sat at his old-fashioned wooden desk in a large office in Sarajevo. Drew is a friendly and good-natured middle-aged man with graying hair and a goatee. His style and demeanor resemble a professor at an American university, but he leads a slightly more dangerous life: Drew is the co-founder and one of the leaders of an international organization that has put the fight against corruption and organized crime right in its name: the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project — OCCRP. It networks, unites and assists investigative journalists from all over the world. In 2019, he was doing just that from Sarajevo. The building that served as the headquarters of the international organization, which regularly raises politicians’ and mobsters’ blood pressure, previously belonged to a railway company. In the office where a Yugoslav comrade director once worked, the phone rang. Looking at the name on the phone’s display, Drew remembered the same person calling him a year and a half ago. The day the police found the bodies of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová, Pavla Holcová was the one who called to tell him. Unfortunately, this was not the first time he had received news that a journalist who had cooperated with the OCCRP had been murdered.

“Don’t worry, we’re going to report this. We’re going to get this. People don’t get away with killing a journalist!” he told her on the phone at the time. And though he believed it at the time, he had endured rather disappointing experiences over the following long months. He sent experts to Slovakia, experts who had previously managed to secure evidence in the murder of Ukrainian journalist Pavel Sheremet. Here, however, they were unsuccessful. The police, including high-ranking officials, first promised them access to some of the evidence. They considered the most important to be the video footage from security cameras in and around Veľká Mača from the day of the murder. Video footage had proven crucial in the investigation into Sheremet’s murder. But the Slovak police later backtracked. They indirectly suggested to the OCCRP people that they had been told off by someone “from above.“

“Listen, I got my hands on this great stuff!” Pavla Holcová said this time on the phone, obviously in a much better mood. She began to explain to Drew that he could get a complete copy of the investigation file into the murder of Ján and Martina, but that it was up to 70 terabytes of data. Seventy million megabytes of data, that is.

“But listen, they told me I had to somehow figure out how to get a copy from them myself. So I need you to free up the IT guys to help me with that, to work it out somehow,” Pavla finished.

“Okay, but listen, do you think there’s that video?” Drew asked, his mind still on the security cameras from the village, where Ján and Martina lived and died.

“Drew, you don’t understand. There’s everything.“

The original Slovak version was published on ICJK.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.