Anna Gielewska (FRONTSTORY.pl)

Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY), Tamara Kaňuchová (VSquare),

Tomáš Madleňák, Karin Kőváry Sólymos (ICJK)

Illustration: Mariusz Kula 2025-07-09

Anna Gielewska (FRONTSTORY.pl)

Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY), Tamara Kaňuchová (VSquare),

Tomáš Madleňák, Karin Kőváry Sólymos (ICJK)

Illustration: Mariusz Kula 2025-07-09

- Russians are hunting for the private data of thousands of people they consider Putin’s enemies. They use the data for doxing – exposing them to online attacks.

- Deploying a method that had previously proven successful in Ukraine, they published a list of Poles—activists, politicians and journalists—who support Ukraine.

- The “doxing Wikipedia” includes names from many countries, including Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary.

- In Central Europe, no one is effectively countering doxing.

Kateryna’s husband, Oleksiy (names changed), volunteered for the Ukrainian army in the first days of the war. Kateryna still has the memory of him leaving home in a uniform he had never worn before, with a backpack borrowed from a friend.

They talk for the last time a few months later. Then contact breaks off. After some time, Kateryna gets official information: Oleksiy has disappeared at the front.

Kateryna does not publicize this. Quietly, together with other families, she tries to get more news about his unit: “In time, we already had the names of the entire brigade, we compared the places of disappearance, checked the coordinates,” she says.

The search ends in nothing.

But on Facebook, Kateryna comes across a photo of Oleksiy, uploaded by an unknown woman. The caption under the photo says in Russian that the man is wanted. Kateryna writes to the author: how does she know her husband? Why is she posting his photo online? What is he wanted for?

The stranger’s account immediately disappears.

A week later, threats arrive on Kateryna and Oleksiy’s 6-year-old son’s phone: “There is not much time left for you, Ukronazis,” “We will come for you soon, be careful.” All in Russian, each from an unknown number.

Today Kateryna is convinced that her husband has been in Russian prisons for three years. She has no contact with him. But why did someone threaten her and her child?

Kateryna doesn’t know the answer. But she knows she was not the only one to whom something like this happened. Hundreds of families of Ukrainian soldiers have experienced similar situations.

Kateryna and others are victims of doxing. It’s a stalking technique used by the Russians to obtain and make public private information online to intimidate or harass victims. The ammunition in these attacks can be a home address, phone number, workplace or other sensitive data.

Until recently, such activities accompanied fighting on the Ukrainian front. In our investigation, we look at how doxing has infiltrated the internet in Central Europe.

The investigation is a result of a joint research project, ANTI-DOX, by FRONTSTORY.PL, VSquare and the Hague-based think-tank International Center for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), supported by EMIF. As part of the investigation, we jointly analyzed Russians’ tools for collecting and publishing data online, as well as bots and channels on Telegram. Together we traced the activities of doxing groups, interviewed victims, and reconstructed the paths by which doxers obtained data on victims.

Fear for Them and for Themselves

New posts asking for help are appearing daily on social media in Ukraine. All appear similar:

“He has given no sign of life for five days.”

“He has gone missing without news.”

“Help find him.”

Relatives publish photos, names, surnames, dates of birth, unit numbers, places of last contact.

For families, such announcements are often a last resort. For the Russians, however, they are valuable information. They can serve as intelligence materials and help apply future psychological pressure.

According to Mykola Balaban, deputy head of the Center for Strategic Communications of Ukraine (Stratcom), doxing is one of the key tools of Russian information and psychological warfare. It is meant to create an atmosphere of fear, to weaken morale. To destabilize the opponent’s base.

This is confirmed by Maria Pavena, a specialist working for the Ukrainian government on the search for missing persons in the central and northern regions of Ukraine. On a daily basis, Pavena works with families who have lost contact with their loved ones, helping to get information and advising on how to respond in similar situations. She hears horror stories about victims of Russian doxing.

“Scammers found a contact for one woman on social media and demanded $15,000 from her,” she says. “They threatened that if she didn’t pay, her relative, who is in captivity, would spend the night naked outside. They sent a video as proof. After she told them that she had no such money, the contact stopped.”

What can be done in such a situation? “The only effective action is to immediately report the matter to the police,” says Maria Pavena.

Few victims go to the police with blackmail, however. “Victims know that it will not improve their situation. The only thing some of them hope for is that the perpetrators will suffer punishment later.”

Data Collected, But for Whom?

Valeria, another FRONTSTORY interviewee whose husband disappeared in the war in 2023, is looking for him in many ways. She publishes information on Facebook groups and leaves data on online sites that promise to contact her when information about the missing man comes in.

In May 2022, well-known presenter Kateryna Osadcha, together with 1+1 TV, launched a project in Ukraine called “Find Your Own” (“Знайти своїх”) — a promise to help find people with whom contact has been lost on the front lines. The initiative operates on the Internet and television: every day, viewers can see photos of those sought by their families. But the project focuses exclusively on civilians.

Screenshot from the poshuk.1plus1.ua project website.

Following the launch of an official channel on Telegram and a bot called poshuk_znyklych (“search for missing persons”), which publishes profiles of missing civilians, unofficial sites collecting information about soldiers started appearing online. One of them is the (now defunct) poshuk.space, which is linked to a Telegram bot, and which impersonates Osadcha’s official site. The bot prompts the entry of real data about missing soldiers.

Valeria used another such site: Wartears.org: “To report a missing person, one had to enter a name and date of birth, and then describe what the last contact was like. The site promised to notify us when new information became available, in fact it was collecting data on her husband. No one contacted me. Only my husband’s photo and personal information appeared on the site.”

Wartears service was launched in May 2022 in Russian, Ukrainian and English. It publishes lists of exchanged POWs and news from the front. According to the creators, the database contains data on 125,000 Ukrainian veterans.

Screenshot from the Wartears.org website.

The database is bizarre, to say the least. The numbers on missing Ukrainian soldiers are verified based on statements by Sergei Shoigu, secretary of Russia’s Security Council, and some Ukrainian units are listed as “nationalist groups.”

Waste From the Propaganda Machine

According to Russian media, Dina Shubina is behind the Wartears project. Who is she? Probably a stooge. There is no information online about her career, place of origin or activities.

So who is actually behind the site?

FRONTSTORY has determined that it was registered in the name of a Russian, Oleg Makarov. We obtained RDAP (a system for retrieving information about domains) data, from which it appears that the site was registered to Makarov before these details were hidden. Today, these details are not officially available.

The man is professionally involved in cybersecurity, and appears in Russian media as an expert on the use of combat drones. He also leads tours of Moscow’s WWII shelters. Two years ago, he appeared on the program of Vladimir Solovyov, the Kremlin’s top propagandist, as the organizer of a Russian Defense Ministry-backed military forum.

Got a Message From Putin

Artur (name changed), commander of a Ukrainian battalion, only spotted information about himself on Russian channels in 2022, although he had been fighting in Donbas since 2014. Artur is affiliated with the Azov unit (formed in 2014 in response to separatists in Donbas; today it is part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces).

In February 2022, Artur came across information about himself on the Nemezida website, which publishes data on Ukrainian soldiers. He ignored it. After all, the phone number provided was wrong, and some of the photos attributed to him depicted completely different people. “Most often we ignore such threats,” Artur says, shrugging his shoulders.

But according to Mykola Balaban, deputy head of Ukraine’s Stratcom, doxing is a systematic campaign, with open sources and precise actions targeting soldiers—and their loved ones.

Since 2022, personal data has been used to send SMS messages en masse along the front lines. This is one way to demoralize Ukrainians and create panic. How does it work? When Ukrainian soldiers’ phones are close to the border, Russian services intercept data from their handsets and use it to send threats to their families.

Russia is also attacking foreign volunteers fighting on the front lines in this way.

There are posts on Reddit in English in which those planning to join the Ukrainian military ask how to minimize the risk of data leaking online.

The concern is justified. One of the key tools of psychological influence in this war is the ForeignCombatants website.

A Handy Wikipedia of Vilification

At first glance, the site resembles Wikipedia. In fact, it is a database that has private information on hundreds of people from around the world who have supported Ukraine in some way. There are data on, among others, 61 citizens of Poland and Polish organizations, as well as similar profiles of citizens of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and many countries around the world.

The service was described by OKO.press in April. Most of the data—including photos—comes from open sources, primarily from social media.

How can you appear on such a list? For any form of support provided to Ukraine—not necessarily participation in frontline activities.

Polish profiles on the list are dominated by volunteers, journalists, and politicians. The database includes Gazeta Wyborcza’s first deputy editor-in-chief Roman Imielski, General Rajmund Andrzejczak, Law and Justice (PiS) MEP Malgorzata Gosiewska and former Polish ambassador to Ukraine Bartosz Cichocki. Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski found his way to the site after his visit to Kyiv in January 2023.

Along Trzaskowski’s, profiles on Foreign Combatants were also created for the mayor of Bratislava, Matúš Vallo, the mayor of Prague, Zdeněk Hřib and the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, most likely for the same group visit to Kyiv. Admins added a picture from the train including all mayors and their individual pictures with the mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko.

Some of the people on the list we contacted learned about its existence from us. “I had no idea that such a ‘biography’ of me existed. The data is from publicly available sources, except for the nonsense about my attitude to western Ukraine (I have no idea which of my statements they could have so misrepresented—I was known for my ‘Jagiellonian’ rather than nationalist views). I also do not believe that I was ‘one of the main instruments of Poland in Ukraine,’ although that’s a nice thing to read,” replies Robert Czyzewski, director of the Polish Institute in Kyiv, to our request for comment.

Former Civic Coalition (KO) deputy Hanna Gill-Piątek, a councilor of the Łódź assembly, has a different reaction: “When I was an MP I used to get emails with threats like ‘I’ll cut off your head.’ Reports to the police yielded nothing. Just early last week, I received a phone call from an unknown number and heard vulgarities in a Russian accent.”

We also contacted the office of Matúš Vallo, who also didn’t know about his profile, but commented that all information was previously made available elsewhere. “So far we have not recorded any attempts to penetrate the city’s systems or other security incidents that could be related to the profile on the mentioned site. As for the mayor’s personal accounts, in January 2024, there was a coordinated attack on the mayor’s social media accounts, during which they were flooded with tens of thousands of fake followers and numerous comments originating from countries outside Slovakia in a short time. The origin of the attack, however, is unknown,” replied Peter Bubla from the Department of Communication and Marketing of the Municipality of the Capital of the Slovak Republic, Bratislava.

On the list we also came across the Open Dialog Foundation, which carried out humanitarian missions in Ukraine. The site published the details of all its employees. “We regularly encounter aggression in various forms, most often online. We sensitize new employees to such situations,” says Bartosz Kramek of the foundation. “We ourselves publish information about our activities in Ukraine and, as far as we know, the ForeignCombatants service relies mainly on publicly available sources.”

We asked Polish institutions (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration, NASK) whether they took any action regarding the existence of the ForeignCombatants and similar websites. The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote back: “We kindly inform you that due to security issues, the MFA does not provide information on this subject.”

The Scent of Aristocracy and Propaganda

ForeignCombatants is the work of professionals. In June 2022, the Russian Foreign Ministry published a Facebook post in which it revealed that the service is a database of foreign mercenaries and volunteers taking part in operations on the Ukrainian side, created by Telegram’s Rybar and Vatfor channels. The goal of the project? “To convince mercenary soldiers to abandon their role as cannon fodder, and to show that the Ukrainian authorities treat them like disposable pawns.”

Let’s have a closer look at these two Telegram channels. Rybar is a well-known, pro-Russian channel, with more than 1.2 million subscribers. It publishes detailed military reports and maps of the fighting, as well as the coordinates of the positions of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and Ukrainian strategic facilities. Despite its obvious pro-Russian engagement, Rybar has been cited by CNN, Bloomberg and the American Institute for the Study of War (ISW).

According to The Bell, an independent Russian outlet, Rybar may have ties to Russian services. The Bell has established the identity of one of the channel’s authors: Denis Shchukin, who calls himself a “political strategist” and “a representative of the old aristocracy.” In reality, he is a 44-year-old Moscow programmer.

Another Rybar author is Mikhail Zvinchuk, a former employee of the Russian Defense Ministry’s press team. Both men are linked to the Internet Research Agency, the well-known Russian troll farm. In 2019, about a year after Rybar’s launch, it caught the attention of Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder of the Wagner Group and the Internet Research Agency. He provided the channel with funding—and Rybar got its own section on Prigozhin’s site.

After staging a failed coup attempt, Prigozhin, along with the plane and the people he traveled with, was shot down by Putin’s regime in 2023. What then of Rybar? Today the channel earns money from advertising and publishing “posts from verified customers.” Prices range from 200 thousand rubles (about 2 thousand euros) per post. The channel has news contracts with, among others, Russia Today and the anonymous Z-channel network, linked to Sergei Kiriyenko, the first deputy head of the Putin administration.

Between Moscow and Bratislava

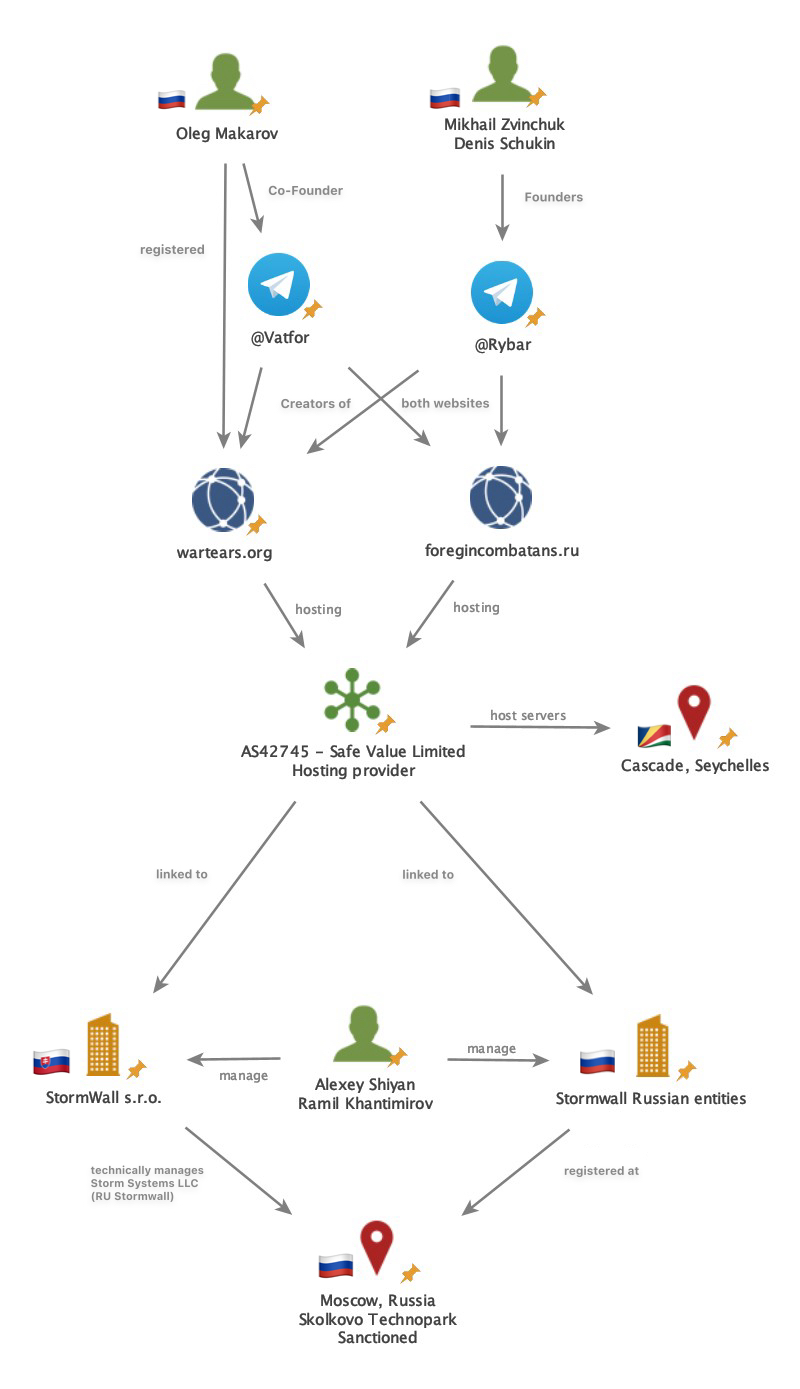

What do the Wartears website, which collects data on Ukrainian soldiers and their families, the doxing Wikipedia-esque site ForeignCombatants and the Kremlin-supporting Telegram channels have in common?

These are all part of the Kremlin’s information warfare infrastructure. The Pentagon pointed to them as early as 2023 as projects of a Russian operation that collects data on Ukrainian soldiers and their families.

Our investigation of doxing sites leads us to the Seychelles—and to Bratislava. We decipher the web of connections between people and channels that rat on soldiers and their loved ones. It’s a complex puzzle designed to mask their ties to the Putin regime.

The ForeignCombatants and Wartears domains (both created within the same seven days in 2022) are hosted by Seychelles-based Safe Value Limited, whose only route out to the internet is through Moscow-based Storm Networks and StormWall.

“This alongside other indicators strongly suggests these entities are likely managed by a single decision-making center,” says an expert from DomainTools, a cybersecurity company.

Storm Networks is one of several interconnected companies around the StormWall brand. One of the companies in this network, Storm Systems, also owns the StormWall trademark. The same Storm Systems lists in its records an address of the so-called Skolkovo incubator, a sanctioned Russian center known as the Kremlin’s “technological forge.” Experts at Domaintools suspect that the complex system of technical links may deliberately serve to maintain the appearance of having no ties to Russia.

A StormWall company connected to Russian entities has been registered in Slovakia since 2017. The company’s headquarters in Bratislava contrasts with the modern image it presents online. It is located on the edge of the Podunajské Biskupice district, on the outskirts of the city, adjacent to fields and meadows. No one is in the office in the middle of the day, when an ICJK reporter visits it. Last year, Slovak records show the company had €1.5 million in revenue.

Interestingly, one of the companies around StormWall, Russian Storm Systems, also provided hosting for NewsFront, a Russian propaganda site operating in a dozen European countries (we wrote about NewsFront’s activities in previous VSquare investigations here and here).

Behind StormWall s.r.o. are two Russian entrepreneurs: Ramil Khantimirov and Alexei Shiyan. According to data from official Slovak records, the owners of Stormwall declare permanent residence in Bratislava as of May 2025.

StormWall’s headquarters in Bratislava.

Khantimirov, a graduate of a St. Petersburg business school, is active in cybersecurity. Little is known about Shiyan, who is less publicly visible; in the past, he worked for a Russian Ministry of Economic Development.

We asked StormWall, as well as Ramil Khantimirov, to tell us about the relationship between the parties we described. By the time this text was published, we had not received a response.

“Ekaterina II” Incites After Hours

In March 2023, the Telegram channel TrackANaziMerc (TaNM), which tracks foreign mercenaries fighting for Ukraine, published a thank-you note for helping to expose “hundreds of mercenaries and ukro-nazis.” It lists ForeignCombatants.

While experienced propaganda players are behind the ForeignCombatants database, the painstaking digging of private data from the network is probably handled by volunteers on Telegram, according to our research.

Back in 2022, the activity of the TaNM channel was limited to publishing photos and short bios of “enemies of Russia.” It was a coordinated operation: a user who wanted to join the data collection could get the status of a lower-level administrator. They would then be given access to a closed chat room, where the doxing operation was coordinated.

The TaNM channel became popular a year after the all-out assault on Ukraine thanks to promotion by Vladimir Solovyov, the Kremlin’s top propagandist, among others. Today, it’s a large international channel in English with nearly 60,000 followers. It is one of the main sources of data for the Kremlin’s propaganda sites. A closed chat room for volunteers, where information about people supporting Ukraine is exchanged, has more than 5,000 participants.

The operation is managed by an informal group called The Dirty Rats. Its members care about anonymity, carefully masking digital footprints. But the identity of the administrators was recently discovered by the independent OSINT group The Unintelligence Agency (TUA): the owner of the channel is Daria Khalturina, publishing under the pseudonym “Ekaterina II.”

After hours of action on the net, “in civilian life,” Ekaterina II is the head of one of the institutions at Russia’s Health Ministry. Online, she regularly replicates the Kremlin’s narratives.

Who Drove the “Polish Executioners”?

In 2021, at the height of the migrant crisis at the Polish-Belarussian border, an anonymous channel called “Polscy Kaci” (“Polish Executioners”) appeared on Telegram to intimidate and discredit the Polish Border Guard officers.

The channel was created at a time when a state of emergency was in effect at the border. “Polscy Kaci” (“Polish Executioners”) published images of guards, their phone numbers and social media photos. Most with offensive comments and allegations of crimes against migrants.

Screenshot from the channel.

Much of this information turned out to be false or manipulated, but some of the data was authentic.

A report by the Polish Committee to Investigate Russian Influence has identified the “Polish Executioners” channel as a Belarusian intelligence operation. The case was investigated by the Radom District Prosecutor’s Office. According to the prosecutor’s office, the guards’ data came from old visa applications submitted by guard officers. However, the prosecutor’s office did not establish how many officers were involved, in what years the applications were submitted, or whether they were submitted for private or business trips. It is also not known how data from the Belarusian bases reached the “Polish Executioners” Telegram channel.

The investigation into the case was discontinued on February 27, 2025 due to a failure to detect the perpetrators.

According to the Polish Border Guard, apart from this one situation, officers have not encountered mass doxing.

However, a footnote to the committee’s report reads: “The new account by “Polscy Kaci” seamlessly transitioned from stalking Polish Border Guard officers to attacking Ukrainians in a manner consistent with Russian narratives after full-scale aggression in 2022.”

In the finale of the third season of the Black Mirror series, released nine years ago, autonomous insect drones kill their victims based on data from the internet. At the time, this dystopia seemed to be nothing more than an artistic, entertaining vision.

Today, it is becoming a reality. The only difference is that instead of drones, Russian volunteers from Telegram are hunting their victims based on data from the internet.

Doxing poses a challenge to legal systems. We asked institutions in Poland, as well as the neighboring Czech Republic and Slovakia, how they are approaching the problem.

The Polish Ministry of Justice explains that doxing is not a separate crime under Polish law. However, it can be classified as stalking, defamation or illegal solicitation of information. The most common actions in such cases are the initiation of criminal proceedings, securing data on the internet, imposing a penalty and, in some cases, a ban on contact or an order to refrain from certain activities.

There is also no separate criminal provision for doxing in Czech law. “It is an act that can be of a very diverse nature,” explains Hanna Malá from the communications department of the Czech Interior Ministry. “Therefore, each time the legal qualification depends on the specific case: it could be a crime of unauthorized access to a computer system, a violation of the confidentiality of transmitted information, or a violation of RODO regulations [the Czech Office for Personal Data Protection is responsible for enforcing the latter – ed]”.

Slovak police spokeswoman Martina Sláviková responds similarly. In response, she stresses that the term “doxing” is not in the Slovak Criminal Code, but that actions of this type—depending on their scale and consequences—can be classified as dangerous electronic harassment or violation of the rights of others, among other things.

Sláviková adds that police do not keep separate statistics on doxing. These cases are recorded under other crime categories.

Why doesn’t Telegram block sites that directly incite hatred and murder?

The platform has not answered our questions for months. Last August, police in France detained Telegram’s owner, Pavel Durov. French prosecutors accused him of not doing enough to moderate toxic material on Telegram.

We collaborated on the technical part of the investigation with DomainTools Investigations. The technical investigation by DomainTools is available here.

The Polish version of this investigation was published on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Join a webinar to learn more about the findings of this investigation. Register here.

More on doxing in ICCT reports:

https://icct.nl/project/anti-dox-identifying-evaluating-and-countering-disinformation-times-war

https://icct.nl/publication/testimonies-victims-russian-extremist-doxing

https://icct.nl/publication/doxing-literature-review

The project “Anti-Dox: Identifying, Evaluating and Countering Disinformation in Times of War”, is supported by the European Media and Information Fund – managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian foundation.

The authors bear sole responsibility for the contents of EMIF (European Media and Information Fund) supported publications. These contents do not have to reflect the positions of EMIF, its partners, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute (EUI).

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Warsaw-based investigative and data journalist at VSquare and Frontstory.pl, Anastasiia Morozova previously collaborated with leading media outlets in Ukraine (Radio Free Europe, Slidstvo.info). She was shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2022) and was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.

Anna Gielewska is co-founder and editor-in-chief of VSquare and co-founder of Polish investigative outlet FRONTSTORY.PL. She is also vice-chairwoman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). A journalist specializing in investigating organized disinformation and propaganda, Gielewska was the John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2019/20) and has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2015, 2021, 2022) and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Award (2021, 2023). She was the recipient of the Novinarska Cena in 2022.