Collaboration: Madalina Voinea (Expert Forum), Ana Mocanu, Matei Vrabie (Funky Citizens), Attila Biro (Context)

Photo: Shutterstock 2025-10-06

Collaboration: Madalina Voinea (Expert Forum), Ana Mocanu, Matei Vrabie (Funky Citizens), Attila Biro (Context)

Photo: Shutterstock 2025-10-06

On the night of Sunday, September 28, 2025, the Moldovan parliamentary election day, many people were holding their breath, waiting for the final results to roll in. Moldovans had faced months, if not years, of an information onslaught at levels beyond what just about any society has faced. In the end, the pro-European ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won 50.2% of the vote, while the pro-Russian Patriotic Bloc managed only 24.2%, despite well-documented foreign interference, mainly from Russia and pro Kremlin actors.

The result was a breath of fresh air, not only for pro-EU Moldovans, but for EU partners who feared another country of the eastern flank falling for Russian propaganda. Only this year in February, the European Commission had pledged €1.9 billion to help Moldova build infrastructure necessary to speed up the country’s EU accession process. Still, despite the result of the election, the potential cost of years of Russian disinformation in Moldova on this small, strategically located neighbor to Ukraine and EU member state Romania remains significant. And the path towards the EU, which faces many hurdles to begin with, will remain a challenge.

“The main takeaway from our observing mission – and something we’ve noticed for a while now – is that election day comes with an overwhelming silence. This silence tells us clearly that the primary manipulation tactics and the game were already implemented well before election day,” said Ana Mocanu, executive director at Funky Citizens, a pro-democracy NGO.

“What we’re witnessing is that election day merely harvests the results of a much broader, long-term manipulation mechanism. This deafening silence signals that traditional vote manipulation tactics are no longer the main concern – electoral fraud, ballot box tampering, and polling station irregularities have been superseded. The real battle is now fought in digital form or at the grassroots level offline, through networks that are already organized and synchronized by election day. This should serve as a clear warning for us: even though Moldova’s elections have just concluded, the networks of influence for the next electoral battle are most likely already being constructed,” said Mocanu.

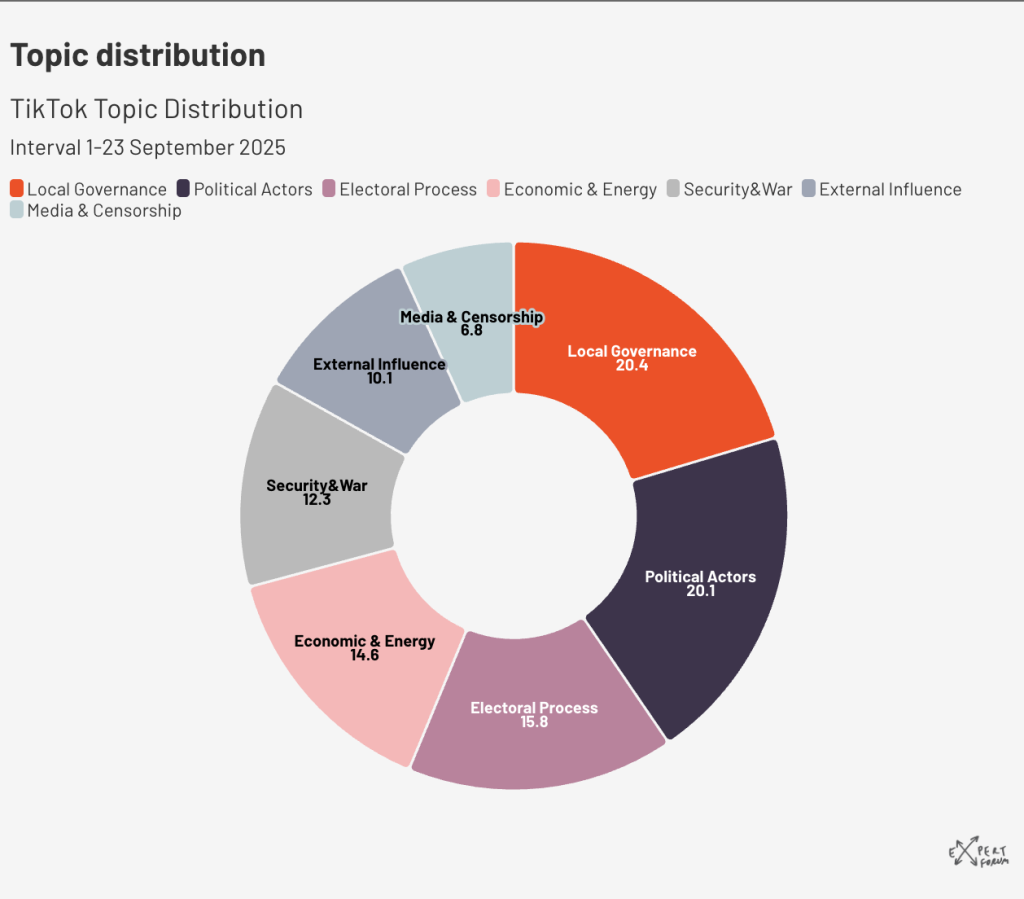

Moldovan elections withstood nothing less than an AI-fueled propaganda machine that ran continuously. The scale was unprecedented: in three weeks (between September 1 and 23), 9,900 TikTok videos were published and generated over 93 million views, created with artificial intelligence.

Source: Fact Hub

This model is already being replicated outside Moldova, as we’re seeing in investigations into the October 3-4 Czech parliamentary elections. Over the course of arguably the most important elections in recent times for Moldova, the Kremlin playbook of information interference advanced in quantity and quality. And the shared information space between Moldova and Romania is effectively an open passage to the EU.

“When I began this monitoring work, I anticipated a manageable volume of content to track in a small country compared to what we’ve been through in Romania. The reality proved far more challenging, not because of the narratives themselves, but because of the sheer scale of their artificial amplification,” said Mădălina Voinea from Expert Forum.

“The critical issue isn’t that these views exist in Moldova’s political discourse. If these narratives were spreading organically through politicians and citizens who genuinely share their beliefs, that would be about democratic debate. Instead, what we’re witnessing is the hijacking of Moldova’s information ecosystem through artificial armies of inauthentic accounts that manufacture chaos. Fear-mongering dominates this coordinated operation, in my opinion,” said Voinea.

According to an investigation by Context, a bubble of 128 TikTok accounts was characterised by its AI-generated video content. Over 6,000 clips, published over the course of 2 months spread disinformation and polarising narratives. The production mechanism was simple; overwhelm the fact-checkers and platform moderators with low-cost content.

Less than a month before the election, Expert Forum conducted an analysis of 3,391 videos, 36,338 comments, and 100 identified inauthentic accounts on TikTok. The pattern is the same: AI-generated fake accounts create an incredible amount of views in a short amount of time (13.9 million views in Moldova’s trending content during the month of the research). As the LLMs create automated tools to create different users, profile pictures, and original content.

So what are the examples of some of these fake online personas? Conventionally attractive people on profile pictures promote political messages, exploiting one of the most basic psychological biases; we are more likely to receive and adopt a message from someone we perceive as attractive (or at least not anonymous). Another tactic is including posts that are familiar, such as “your auntie with flowers”–an Eastern European woman, carrying flowers as if they are from your grandma’s garden.

Meet Vasile Costiuc, a “Viral” Candidate

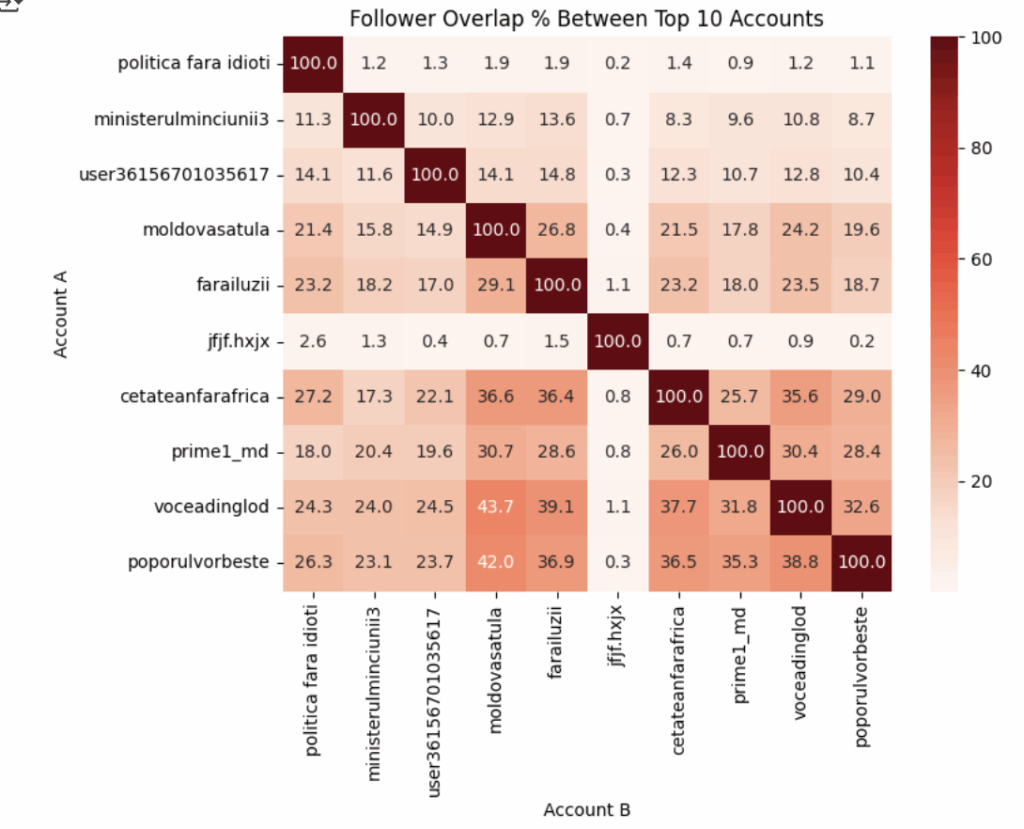

One question you probably didn’t think to ask: How many TikTok accounts do you need to generate 1 million views in 7 days to promote a Moldovan parliamentary candidate Vasile Costiuc? The answer is 17, as Expert Forum determined in their analysis of inauthentic behavior.

Vasile Costiuc and George Simion, Source: Facebook Vasile Costiuc

Vasile Costiuc is not a new political figure in Moldova’s politics, yet his promotion on social media sparked much attention, especially since his party, Democracy at Home, managed to enter the Parliament, with polls showing him at around 1.8 –3% of the needed 5% threshold.

Costiuc is the president of the Democracy at Home party, an informal “friend” of Romania’s AUR party, and its leader George Simion. The two have engaged before, with Costiuc campaigning for the AUR back in the Romanian presidential elections. Besides his AUR-related activities, he also actively participated in fighting corruption – in sometimes real, sometimes alleged cases. Previously, there were reports of him taking part in events organized by general Alexandr Kondyakov from the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB).

While we have come to understand that TikTok can produce “random” virality, the question is how much of this virality can be tracked to actual people. Expert Forum investigated how much TikTok activity is based on real users. They identified 417 videos that promoted Costiuc and his party in a week, posted by 17 accounts. Then for 16 of those accounts, they analyzed the followers which showed a medium/high risk of CIB (coordinated inauthentic behaviour), which showed itself in having no posts or many deleted posts and a big overlap in followers between the 16 accounts.

Source: Expert Forum data

An American Saving the Orthodox Church

Fear-mongering is present across narratives that take shape in different ways: economic problems, moral decay, fear of losing sovereignty, or neutrality. Neutrality is inscribed in the constitution of Moldova, and is an important aspect in the ethnically divided country. A big topic is also the Orthodox Church and the alleged “persecution” of Christians. One of the main actors of this narrative is Charles Jacob Bausman, an American pro-Russian activist who participated in the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Bausman’s ties to extremist groups in the U.S. are well documented, and he is presented as a savior who can “destroy the myths created by the Western media.”

His mission in Moldova was to “expose the situation around the Orthodox Church“ and the alleged violation of believers’ rights. He didn’t go there alone – a group of international bloggers who were supposed to come with him. According to a Hatewatch investigation from 2021, based on leaked emails, Bausman is tied to a Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev and was asking for funding via his associate. Malofeev is infamous as the source of money for pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine and is subject to international sanctions.

Ilan Shor’s Money

The fugitive oligarch Ilan Shor is known for his connection to the biggest bank fraud of Moldovan history, and he is also a chairman of the now-banned Shor party. He was connected to the Russian influence operation during the EU referendum vote in 2024 (on his role, here’s a previous VSquare analysis, based on a Moldovan intelligence report). Currently, he is based in Moscow, sanctioned by the U.S., the UK and the EU. Shor’s network funnelled money into Moldova’s social media. The Russian-sponsored network invested €45,000 into advertising on Meta during the period between April 30 and July 28, with Shor personally being the main sponsor.

Shor did not limit himself to Meta. He created a network on Telegram. In just 13 minutes, the network launched 30 channels from Russia to target the parliamentary elections. A data leak revealed that 134 activists were behind these channels, and were paid €1.8 million in 2024 and €1 million for the first five months in 2025. The channels were claiming to publish local news for cities in Moldova, but practically they were just amplifying messages from pro-Russian candidates, along with AI-generated content.

During the election day on September 28, 2025, Pavel Durov, the CEO of Telegram, wrote a post on X, disclosing his alleged communication with French authorities over taking down channels on the platform a year ago, during Moldova’s presidential election in exchange for a more favorable image during his court case. He further accused French and Moldovan authorities of silencing channels. The French Foreign ministry called him out on the choice of timing to make such an accusation.

“In Moldova, it’s a very specific market because they are using Telegram as a media platform. So most of the time, Meta it’s just a platform for communication, but Telegram it’s for mainstream media to communicate with people. We are seeing that there is a lot of this information that can not be regulated anyhow because they are not under the DSA,” said Matei Vrabie, the coordinator of the countering disinformation programs at Funky Citizens.

Divides in Moldova

“This fearmongering is particularly effective in Gagauzia and Transnistria, regions where communities genuinely feel neglected by the central government and excluded from Moldova’s pro-EU trajectory. Their sense of abandonment creates a vulnerability that the Kremlin actively exploits, working to reframe EU accession not as an opportunity for development and integration, but as an existential threat to these communities’ identities and autonomy. However, the limits of this narrative’s effectiveness can be seen even in Transnistria, where despite intense Russian influence and anti-EU propaganda, the pro-EU governing PAS party still managed to secure nearly 30% support,” said Voinea.

With EU member Romania on Moldova’s western border, and roughly one-third of Moldovans holding Romanian passports, the country risks becoming a gateway for Russian influence into the EU, an ideal staging ground for hybrid operations in the European Union, and a new pressure point to enhance Transnistria’s military footprint.

“In Moldova, people have been living with the disinformation in their daily lives since three years ago. I can make a comparison here. Public authorities in Romania don’t communicate too much regarding our problems and our disinformation landscape. Authorities in Moldova are much more prepared in this field and they are debunking – on what is happening in the country, warn against specific scams related to elections, accepting money for their votes and are using their official channels to communicate with the public. In Romania, this kind of public service is missing. They also have a center for countering disinformation that started three years ago. So they are aware that the situation is bad in their country regarding disinformation and there are efforts to counter it,” said Mocanu.

A Brief Background of Moldova’s Politics

Since gaining independence in 1991, Moldova’s politics have been highly divided, shaped by the unresolved Transnistria conflict, tensions in the autonomous region of Gagauzia, chronic elite corruption scandals, and periodic reform waves that culminated in the rise of the pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS).

The “old Moldova” political elites are still powerful. An exquisite example of their level of corruption is the 2014 bank fraud or “theft of the century” that siphoned about $1 billion (-12% of the country’s GDP) through three banks and was later tied to fugitive oligarchs such as Ilan Shor. The case has become an emblem of state capture under Pro-Russian politicians.

On 20 October 2024, voters narrowly approved a constitutional amendment to anchor EU integration, an outcome validated by the Constitutional Court, while authorities battled unprecedented Russia-linked interference, from vote-buying schemes to crypto-funded operations ahead of the 2025 vote.

Moldova’s Future Within the EU

“Moldova is doing exceptionally well in adhering to the European Union. Of course, it’s the discussion of, will it join at the same time with Ukraine? There are challenges ahead and we’ll see in the upcoming months how it unfolds, while the EU needs to consider not disappointing a population that eagerly want to become part of the EU” – said Voinea

With a parliamentary majority, president Sandu should have the upper hand in passing legislation that will push the integration process. However, the impact of Russian disinformation operations does not end with election day. The undermining of trust in government and public institutions that took place in Moldova could have merely been a testing stage for tactics that will soon be visible in the rest of Europe.

During the election monitoring in Moldova, Expert Forum worked alongside Context.ro in FACT, an independent, non-partisan hub launched in mid-2025 under the umbrella of the EU Digital Media Observatory (EDMO). It brings together investigative journalists, social media experts and political analysts and it is coordinated by Context.ro.

We received editorial support from Graham Griffith (Transitions/TOL) and Transitions media in Prague to compile this overview. For a refresher of the first round of Romanian presidential elections in 2024, you can read this and this article on VSquare, which came out of a collaboration between Context.ro and Investigace.cz. And this piece from 2023, as a part of the Kremlin Files project.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Tamara is a journalist from Slovakia, currently based in the Netherlands. Besides VSquare, she writes for The European Correspondent.