Until recently, Poland was the biggest recipient of Chinese investment of the Visegrad Group countries and the eighth biggest in the European Union. It is a thing of the past, though. And the future does not look so rosy anymore.

How does China engage in Poland? This question has no simple answer. Polish politicians like to think that, as far as relationships with China are concerned, Poland has a gift from God: its geographical location. The political class is convinced that the Chinese look at the country on the Vistula river with greedy eyes. Indeed, the Eastern European country with a population of 38 million could have several assets – proximity to key partners in Western Europe, access to the sea (potential link with China) or convenient road and rail connections. The Chinese could also be tempted by access to qualified workforce.

They could be…. but they are not, or they are not tempted strongly enough.

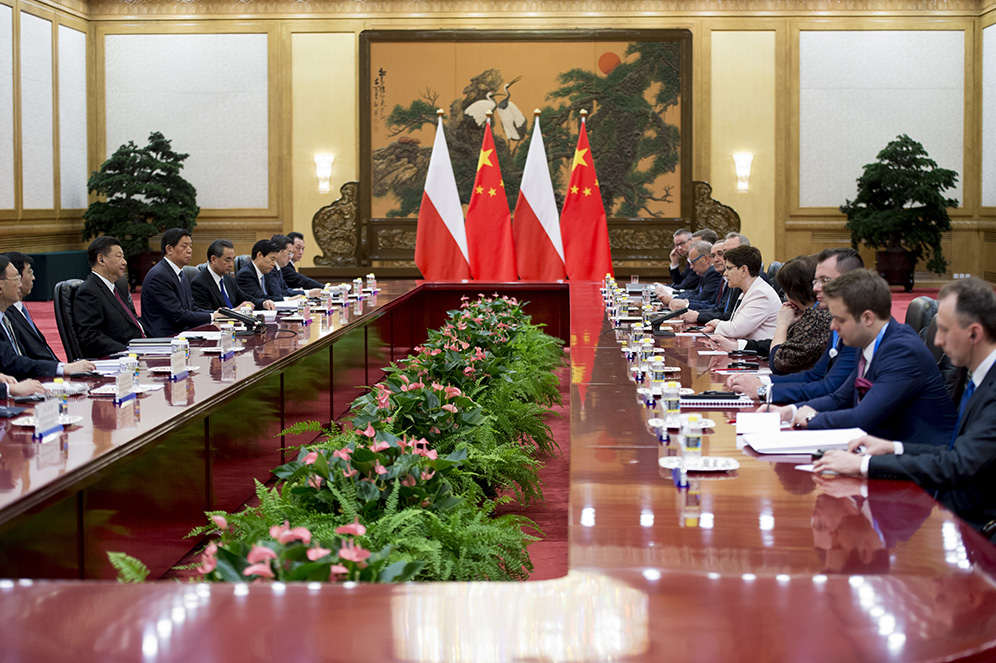

In 2016, Prime Minister Beata Szydło goes to China for a 16+1 meeting. She is happy. She says: “On Chinese Belt and Road, Poland has a chance to become a gateway to Europe”.

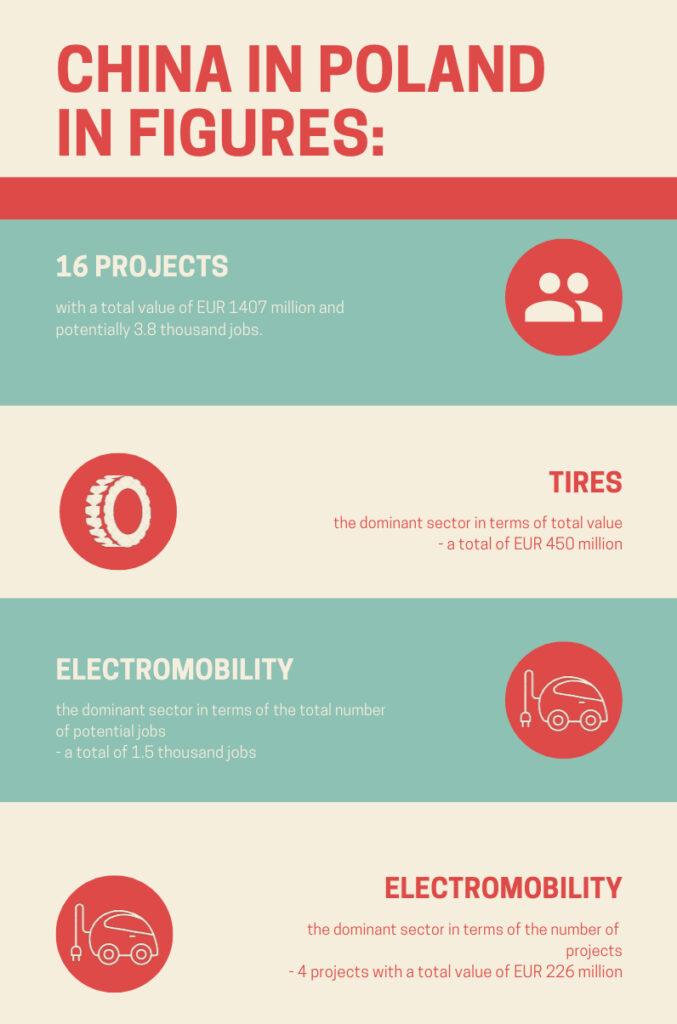

Officially, Chinese direct investment in Poland has grown over the last two or three years. But the figures are not so impressive: according to the National Bank of Poland (NBP), in 2016 the total Chinese direct investment reached EUR 123.3 million, while in 2015 it was EUR 198.5 million.

Admittedly, experts disagree on the methodology: how to calculate Chinese investment in Poland? The NBP methodology does not include investments by companies registered outside the People’s Republic of China – in Europe or elsewhere. For this reason, the Rhodium Group – an independent research provider, for example, reports that about EUR 936 million was invested in Poland in 2016.

Experts agree on one thing: in spite of the growth, the share of Chinese investment in Poland is small.

“China generates more than USD 5 trillion in savings a year and they would like to invest that capital smartly somewhere. Most of the money stays at home, but some of it goes out of the country. It is similar with trade balance. For the past few years, the Chinese have wanted to buy more abroad because their surpluses are so high”, an expert who talked to VSquare believes.

The reception of Chinese investment in Poland is generally positive or at least neutral. This is a change in sentiment compared to 2012, when Covec, the company responsible for the construction of a motorway in Poland, finally abandoned the project. Even so, the debate on this was hushed up and the case did not change Poland’s goal of attracting Chinese investment.

Major infrastructural projects, obtaining which is the objective of Polish-Chinese cooperation as part of the Belt & Road initiative, do not exist. Poland is not on the lookout for cash-rich investors. What the country would prefer are technology and know-how. Cultural differences are also important: Chinese companies are reluctant to take part in public tenders. It is an open secret that they have tried to put pressure on the Polish government so that they did not have to compete on the same conditions as other companies. And Chinese offers of funding often fail to comply with EU regulations on tenders and state aid.

Only 1% of Polish exports go to China. In addition, last year country’s exports to China shrunk by more than 5 percent on a yearly basis, for the first time in this decade. It is the other way round with Chinese imports to Poland, which are growing steadily every year (last year they increased by more than 5 percent, year on year).

Radosław Pyffel, an expert on China says: “The Chinese want to do business mainly with the state here. They want to run a safe business, and for them, the state stands for credibility. But the model that China has used in other poorer regions of the world, ie. investing in infrastructure, does not really work here because we have European funding. Private business, on the other hand, which is unable to obtain money on the market and would gladly reach for Chinese cash, is not so attractive for the Chinese because they do not accept excessive risk”.

Despite the resistance, Chinese companies are slowly setting up in Poland. In what industries? TCL in Żyrardów and Digital View in Koszalin make LCD panels; Nuctech in Kobyłka near Warsaw makes an x-ray inspection system; LiuGong produces machines at Huta Stalowa Wola. Large financial institutions have offices in Poland – branches of four Chinese banks are located in Warsaw, including two of the largest – Bank of China and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (both are branches of their main offices in Luxembourg). But their activities are shrouded in mystery. When we asked for a meeting with Bank of China officials a few months ago, we never got an answer. It is a well-known fact that Bank of China has been involved in refinancing investments in the office sector.

Huta Stalowa Wola is one of the most interesting investments: at the beginning of 2012, LiuGong, the leader of the Chinese construction machinery industry, took over a civil branch of the company (it makes Dressta excavators and loaders well-known all over the world, and LiuGong was interested in gaining access to tracked vehicle manufacturing technology). It was the first full privatization with Chinese capital in Poland.

In 2016, LiuGong Machinery got rid of many experienced managers: one of the foreign dealers of the Polish company went bankrupt and the investor recorded a loss of over 40 million in sales. Production could not be increased as much as promised. A significant portion of the crew was laid off and the Chinese are winding up production at Stalowa Wola.

Sinohydro, the main Chinese state-owned hydroenergy contractor, has been building a Lublin-Chełm power transmission line since 2015. Since 2016, the same company has been engaged in a project to deepen and expand the channels of the Wrocław waterway system.

In 2016, when Law and Justice decided to finish off wind farm owners, the Portuguese EDPR Group sold 49 percent of shares in a wind farm to a fund controlled by China Three Gorges Corporation (the value of the acquired shares is estimated at EUR 289 million).

Three Chinese companies are listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange: Peixin International Group N.V. (since the end of 2013), a manufacturer of machinery for the production of hygiene products; JJ Auto CG, a company producing parts for vehicles and heavy machinery; and Fenghua SoleTech (since the end of 2014), a manufacturer of footwear components for global brands.

An example of a transaction that may turn out to be a problem, not only for Poland but also for other countries in the region, is the purchase made by a Chinese state-owned company Zhonglu Fruit Juice Co., Ltd. In June this year, Zhonglu Fruit Juice Co., Ltd bought a Polish privately owned company Appol. Appol is considered to be a Polish and European tycoon in the processing of apples, raspberries, currants and other fruits. The Chinese paid PLN 68.5 million for the company’s three plants. Experts agreed that they were paying not only for the plants, but also for a chance to enter the European market with their own fruit concentrates. It is about apple concentrate – the Chinese have been making concentrate for many years, but it is of lower quality (and much cheaper) than that made in Europe. Until now, the EU has defended itself against Chinese entry into that market, protecting fruit farmers and processors by having high tariffs and preventing Chinese companies from taking over companies in that industry.

The acquisition of Appol opens up a way for Chinese concentrates into Europe. What did the Polish government do for the safety of fruit producers? Nothing.

In 2016, with 563 million dollars, and was the largest recipient of Chinese investments among the Visegrad Group countries and the eighth in the European Union.

Experts of Knight Frank, company providing real estate advisory services, have developed a “Belt and Road Index” that evaluates 67 countries recognized as crucial for Chinese investment in the world. Poland was ranked 17th. So much for the figures. According to one of VSquare’s sources, however, in building its own position in relations with China, Poland is doing like a bull in a china shop. To the great displeasure of America, Poland’s strategic ally, the country has become a founding member of AIIB, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, to open opportunities for Polish construction companies to enter the Asian markets.

Experts believe that for China, Poland is still a marginal country, whose attractiveness is closer to that of Russia than Germany.

While Poland has no brand recognizable in China, and it does not look as though it is going to change, the other side has more and more. Huawei, which has increased its share in the Polish smartphone market by 4 percent, up to 27 percent, seems to be the best known Chinese brand today. And the company announces that this is not the end of their expansion.

Justyna Szczudlik, head of the Asia-Pacific programme of the Polish Institute of International Affairs: “A change in the approach of the Polish government to Chinese investment has been visible for a year or two. We are not looking at potential investors as a source of cash, but we are looking for partners who can share their know-how and project experience with us. In this sense, we are more cautious when it comes to Chinese investments. We are sending signals that we are not giving the investors full control over an investment project or the land on which it is carried out. Poland would rather avoid a situation in which an entire project would be funded or controlled by a foreign investor”. This change results from experiences with Chinese investment, for instance in Germany, where China is trying to take over high-tech companies to acquire their technology, posing a challenge even for the security of the state. The Chinese investment in the port of Piraeus in Greece, entirely controlled by the Chinese, is another lesson.

Polish officials are also scrutinizing Chinese investments to create a technology park at Velikiy Kamen near Minsk, Belarus. Ultimately, the burden of the project was shifted onto Belarus. Poles are learning a lesson from the Belgrade-Budapest railway: a flagship investment in the 16+1 formula, which has led to its Hungarian part being subjected to a comprehensive audit by the European Commission.

President Xi calls on politicians taking part in 16+1 meetings for greater openness, cooperation and rejection of protectionism. Meanwhile, Western companies vey often experience that China is the great global economy most closed to foreign competition.

Expert Radosław Pyffel says: “Chinese business is founded on two elements. One is the party, big state-owned corporations and banks. They have let these companies out into the world now, and they are doing well. But there is also the second element, all those small traders, often from Chinese provinces, who will sit with their families somewhere in the world – Argentina, Guatemala, the Czech Republic or Poland, selling slippers, for instance, and counting money. There is a Chinese restaurant in every Polish town, even a small one. Who else would want to do it? They do”.