Blanka Zöldi (Direkt36)

Peter Sabo (aktuality.sk) 2019-05-13

Blanka Zöldi (Direkt36)

Peter Sabo (aktuality.sk) 2019-05-13

We have identified a trail leading to a company owned by the Polish State Treasury in a VAT mafia case – a gigantic international tax fraud carousel, in which companies from Slovakia and Hungary are also involved.

We do not know what Jan Max L. looks like – he is a Danish citizen with no Facebook profile, kept in custody in Poland for more than two years. L. is a mystery – his photos have never appeared in the press or on the internet, even though he has been hunted by the police of several countries. He cannot be visited in jail: it has been several years since the crimes he committed, but investigators are still unable to finish off their work with an indictment. There is no chance for a visit.

Neither the Polish prosecutor’s office nor the ministry of justice have boasted about the case of the 52-year-old Dane so far. Why?

As VSquare has found out, Jan Max L. has conned one of the biggest companies in Poland, a state-owned strategic company Tauron, for more than 50 million zloty. Because of L., Tauron has become part of the evil the government is fiercely battling against: VAT carousels.

The man with three identities

Perhaps Jan Max L. sensed that. Once he landed in Poland, no more would be heard of him. Before the extradition decision, he fought like a tiger. His defence counsel appealed to the conscience of Danish judges, citing facts about Polish prisons he found on the internet. “Multiple prisoners in one cell, unacceptable sanitary conditions, detainees have no access to clean drinking water and are only allowed to take a hot shower once every three weeks,” he wrote in support of the appeal.

The Copenhagen court was insensitive to these descriptions dug out online. L. was taken to Poland on 8 March 2017, after 142 days in Danish custody. He landed in custody in Białołęka, Warsaw. We do not know how many times a week he takes a shower. The public prosecutor’s office does not share too much information about what is happening with the Dane.

The first to pick L.’s trail were the reporters of a Danish daily Dagbladet Information and an investigative portal Finans. Thanks to them, we know that in 2013, when L. was dragging the strategic Polish energy company into crime, the Dane was using three passports.

A journalistic investigation into the case was made possible thanks to a project called Grand Theft Europe, coordinated by a Berlin newsroom CORRECTIV. 34 newsrooms from all over Europe, including Vsquare, participated in the investigation. Over the past months, 63 journalists investigated international VAT carousels operating in EU countries. As a result of VAT fraud, the EU budget is losing 50 billion euros annually. It is the biggest tax fraud in history, and part of the money from it is used to finance terrorist activities.

Why did counter-intelligence protection, a secret umbrella that special services hold over state-owned energy companies, fail in L.’s case? Nobody knows.

Gunther Skarin, his former associate, told Polish prosecutors that L. needed three identities and advanced encryption software on his computer. In 2016, Skarin explained to Polish law enforcement authorities that his former colleague was hiding in Dubai, but he sometimes visited European countries, including Denmark (where he would eventually be caught at the end of 2016).

What exactly was L., a man with three identities, doing in Poland? And what are VAT carousels about?

Tracking down the truck

To answer these questions, we need to go back a few years. A truck parked in a forest near the Polish-Czech border will help us understand the causes of international VAT carousels and make sense of them.

”VAT Carousels”, “VAT mafia” – fighting these crimes has been the flagship project of the ruling political party PiS (Law and Justice). A VAT Investigating Committee (run by a young and ambitious PiS MP Marcin Horała) has been hunting the politicians of PO (Civic Platform) for a year. PiS claims that it was the Civic Platform that allowed VAT carousels to grow in strength in Poland. Horała’a committee is looking for evidence that PO politicians actively supported criminals in tax fraud.

Jan Tokarski, a partner at PwC, tax expert and one of the first investigators of VAT carousels does not believe in the conspiracy of politicians and smiles faintly when I mention it. “This problem was growing, creeping in slowly” he explains. “It’s not as if a giant VAT gap appeared out of nowhere and everyone should have been able to notice it. The carousels were gaining momentum gradually, and the biggest cons were slipping under the radar of even the most cautious entrepreneurs, prominent experts, the revenue office and the ministry of finance. This was because people had limited experience. I mean, everyone. For comparison: in France, VAT was introduced in 1958. The VAT directive which amalgamated tax systems across the EU was enacted in the 70s. The local legislature and tax authorities had decades to learn how criminals operate,” Tokarski explains and adds:

“When Poland came out as a relatively ‘young’ country on the map of free-market economies, mafias smelled out opportunity. They started using con methods that had long lost their raison d’être in the West. They were careful in getting their business going, so as not to make things too hot in the new territory.”

Who is the missing trader?

The mechanism of VAT carousels – contrary to the disheartening name – is not complicated. A carousel can exist because international sale of goods between EU-registered companies is taxed at 0 percent. Therefore, an honest Polish entrepreneur who wants to sell goods to a Czech company will invoice that company for a net price only, without adding VAT – and they will do it with a clear conscience. The Czechs will pay, receive the goods and sell them at home to another intermediary, or directly to the customer – but this time they will pay VAT.

This is how things are done in the world of honest people. But in a dishonest version, the Polish company will issue an invoice with no VAT to a Czech sham company. A driver planted by criminals will pack the goods into his truck and set off from Poland in the direction of the Czech Republic. The Polish company gets a forged (as it later turns out) document confirming the exportation of goods into the Czech Republic. Meanwhile, the driver does not reach his destination. He turns around before reaching the border, parks somewhere in the forest for a moment, and then sells the same goods to a different Polish company – this time adding VAT (local transactions are subject to VAT).

Let us recapitulate, to get a better understanding: our dishonest driver buys goods for 100 zlotys, but instead of taking them to the Czech Republic, he sells them to Polish entities for 101 zlotys + VAT. Where is the business here? Well, the Polish driver does not remit VAT to the tax office. Actually, he does not even need to sell the goods for 101 zlotys. Since he does not intend to pay VAT to the tax office anyway, he can easily offer the goods to potential buyers below their market price, for example 90 zlotys. So, he is going to pocket 90 zlotys + 23 percent VAT on that amount. When the tax office realizes that something is wrong and sends an inspection to control the truck driver, the truck is long gone from where it was parked.

Companies such as the one with the truck, which are experts in tax crime, are called ‘missing traders’.

The example with the truck driver has been made up. In the real world, the ‘forest’ roamed by VAT con artists is the territory of Poland (and other EU countries), where the sham companies do their fictitious business.

Everyone is simply trading

Although the mechanism of the VAT carousels is simple and comes down to the missing trader (a swindler pays a net price for goods and then sells them for a price that includes VAT, without paying the tax to the tax office), for many years law enforcement failed to notice what was going on. Why?

Because of buffers. In VAT carousels, “buffers” are companies that pretend to be legitimate businesses. They “softened” the operation of carousels and made them more difficult to uncover. A self-respecting VAT carousel was not made up of vulgar, obvious sham companies. This could have aroused suspicion in the buyer to which the proverbial “truck driver” came with a suspiciously cheap offer. That is why criminals would plant companies pretending to run a legitimate business into the chain of transactions. As a smokescreen, some of them were registered as VAT payers. Some even submitted financial statements and had valid state licenses. They would buy goods from a missing trader and push them out further – to the honest companies.

An entrepreneur in the electronics industry told us: “In a VAT carousel, only the sham or buffer company commits an offence. Everyone else is simply trading. From 2012, the VAT bandits focused on iPhones. Shady phones with stolen VAT went to all mobile operators. I would risk to say that everyone who bought an iPhone at that time was, in a sense, involved in a crime. Here’s a riddle for you: how many iPhones did Poland export in 2015? One million. A fodder beet country became the fourth exporter of iPhones in the world. When PiS was in power, people from state-owned Gas Trading came to my company. They came to me with iPhones. People from the VAT mafia started companies to buy from a sham company and sell on. Companies would be opened under the name of a Ukrainian who had died in Donetsk a month before. Or in a different way: a man would come to a tea wholesaler making a turnover of one million zloty per year in the sweat of his brow. He would make a proposal: sell my iPhones abroad at a 5% margin. The tea wholesaler did not pay VAT, his turnover rocketed to five million and everyone was delighted.”

VAT fraud and state-owned company

People from the buffer companies break their necks to explain to customers why their product is cheaper than other deals on the market. One of the explanations that might calm buyers down is the short term of payment on the invoice. Buffer companies offer goods for 90 zlotys instead of 100, but on condition of payment within three days.

An entrepreneur in the electronics industry said: “90% of entrepreneurs could swear it was business as usual. The date of payment was the key. Fishy products were bought and sold with very short payment dates of two or three days, although 28 days was considered a standard term. This looked believable, because the price was attractive. A better price meant a short payment date. This could be explained.”

“However, in some cases a suitcase of money on the table was a sufficient ‘explanation’. Or a luxury car parked in front of the tradesman’s house” says Jan Tokarski, the PwC expert. “In such a case, the purchaser is no longer an innocent entrepreneur tricked into the carousel, but he becomes complicit.”

But Tokarski adds that the majority of Polish companies taken for a ride on the VAT carousel were unaware of becoming a piece in a criminal puzzle.

Let us go back to L., the businessman from Denmark. He came to Poland in 2013 and started working right away. Formally, he acted as a representative of Castor Energy and was involved in energy trade. Castor Energy was probably a ‘buffer’ – it was supposed to separate Polish energy trading companies from the missing trader. Which, in turn, was a company called Commodity Trading, registered in Poland. According to the public prosecutor’s office in Katowice, after buying energy for a net price from a foreign supplier, the company sold it in Poland for a price with VAT, but never remitted the tax to the tax office.

The chain of transactions tracked by the prosecutors looked like this: Commodity Trading Poland bought electricity abroad, then sold it to Santoni (a company founded by criminals), which sold it on to Castor – whose papers looked much better than the other companies’, and Castor sold it to Tauron and a private company Fiten.

Tauron and Fiten sold on the energy they bought from Castor abroad – benefiting from zero VAT on such transactions. Both Tauron and Fiten, as they were buying with VAT and selling on without VAT, could claim a tax refund from the tax office. Which they received. State-owned Tauron received a bank transfer for 52 million zlotys, and privately-owned Fiten for 38 million.

When L.’s crimes came to light, instead of sending a bank transfer, the tax office sent a tax enforcement officer to both companies. It demanded repayment of more than 90 million zlotys.

Denmark and Italy start investigations

The elements of L.’s carousel fell like dominoes. The first to be caught was a Norwegian company Castor Energy AS (it is linked to the Polish company Castor by Gunther Skarin, L.’s colleague, a member of the authorities of both companies). As our Danish colleagues at Dagbladet Information have found out, the Norwegian Castor was investigated by Norwegian, Italian, Polish and Danish investigators in 2014. Today it is known that the Castor from Norway was a kind of a ‘mother’ of all the other sham companies (except the Polish Castor, there were also Castors in the Czech Republic, Italy and the UK). Through the parent company (based in Oslo), the group controlling the carousel laundered huge amounts of dirty money. Gunther Skarin, the CEO of the Norwegian Castor was fined a million crowns (about 400 thousand zlotys), which he paid and fled to South Africa. Has was not arrested because, according to Norwegian law enforcement agencies, someone else is the brains behind the operation. Skarin is only a front.

Interestingly, after Castor’s case had been revealed, Danish and Italian governments took resolute legislative steps to fight carousels in the energy sector – and introduced reverse VAT charge on electricity. What is it? In reverse VAT charge it is the buyer, not the seller of goods that is required to pay the tax. In other words: the obligation to pay VAT is ‘shifted’ onto the end of the transaction chain, which makes it more difficult to make scams. The reversal of VAT in any sector virtually rids it of VAT mafia, which then moves to another sector or to a neighbouring country, if it happens to have more favourable regulations.

Because the mere fact of uncovering a VAT carousel usually does not mean cleansing or even clarifying the matter. In the Castor case, investigators and tax administration have isolated two threads, each of which can end up in a blind alley, in a pessimistic scenario. The first one is to bring to justice and punish those who bought energy from the buffer. The second: to determine who was the brains behind the whole operation and hold them responsible, which often is not possible.

We asked the representatives of Tauron and Fiten why the companies bought energy from an unknown company Castor Energy. Was the price it offered lower than the market? If so, by how much? What was the business rationale behind those transactions and the resale of energy abroad? How did the representatives of Tauron and Fiten check the credibility of their counterparties?

We don’t answer questions

Tauron did not respond to our questions. The company has an excuse – proceedings in this case are still ongoing (one in the tax office and one in the Regional Prosecutor’s Office in Katowice).

Surprisingly, we have found Tauron’s Management Board’s official position on carousels in the company’s report for 2018. It reads: “Given all the circumstances of the case and case law (…) concerning the right to deduct VAT in a case of unknowing complicity in carousel crimes, where due diligence was adhered to in vetting both counterparties, (…), the Company acted in good faith and should have the right to deduct tax charged on invoices documenting the purchase of energy from the counterparties (…).”

In short: it is all right because we recovered the VAT lawfully.

Fiten’s Board had more to say. Representatives of the company have sent us a statement, in which they claim their negotiations with Castor lasted two months, and in that time Fiten carried out a ‘detailed and comprehensive’ vetting of the company which L. was associated with.

Fiten’s Board claims that prior to settling the transactions with Castor on its VAT-7 returns, it asked the tax office to confirm whether their new customer was a registered VAT taxpayer. The tax office did not indicate that transactions with Castor Energy were in any way risky. On top of that, after Fiten had settled the transactions with Castor, the head of the tax office checked twice (!) if the company could be refunded almost 40 million zlotys in VAT. Each time, the tax office decided that it could.

When L.’s scams started coming to light, the tax office changed its mind. It has carried out proceedings concerning Fiten for the past five years. It is not known when any decision could be made. Since 2016, Fiten has been a zombie – something that is elegantly called ‘a company under restructuring.’

An energy industry analyst told us on condition of anonymity: “The tax authorities realise they have no chance of recovering the money stolen by missing traders in the years 2011-2015. This is why they are getting at businesses that bought goods from sham companies. This is the simplest and actually the only way to recover the VAT. Those companies have to prove they acted in good faith and exercised due diligence in vetting their counterparties. When the tax office rules to their disadvantage, they go to court. But the rulings of Polish courts in such cases are unpredictable – and often favour tax authorities.”

Green certificates instead of electronics

How come two large companies in the energy market were fooled by the Danish criminal? The energy industry analyst said: “It’s simple. Someone came to them with an attractive offer, and they wanted to sell more. Sales people, who get a bonus when they manage to push more goods out on the market, were easily tempted. In 2013, the awareness of energy scams among Polish entrepreneurs did not exist.”

So who did Tauron actually do business with between October 2013 and April 2014?

The man who may know the answer to this question is Gunther Skarin. He has told Danish journalists on Skype that Castor has ‘powerful investors’ behind it. He said that, at the beginning, they made an impression of honest people. “If I had known what I was getting into, I would have definitely not accepted their offer to become a CEO!”

Skarin has talked to Norwegian police several times. From them, he heard that traces of some of Castor’s transactions lead to Dubai. “My principals acted very professionally. There were enormous sums at stake. That is why I am afraid to disclose their names” said Skarin to Dagbladet Information reporters.

Pedro Felicio Seixas, the head of Europol’s economic crime division, explained at his hearing in the European Parliament on 28 June 2018 that in VAT mafia investigations the top principals can be reached very rarely: “We know who these groups are. Some of them have been working continuously for a decade. The people who control them do so from a distance. They are not physically in Europe, which makes it so difficult to hunt them.”

Seixas estimates that 80% of the money stolen from European taxpayers goes into the pockets of two percent of VAT fraud criminals who operate in EU states. They are a mafia elite, sweeping up the lion’s share of the profits from illegal activities for themselves.

Trading in electricity and the so-called ‘green certificates’ is one of their favourite sectors of the economy today. To do these scams, you do not need trucks, pallets or boxes filled with merchandise that circulates between warehouses and never reaches the consumer. To sell electricity, all you need is a few clicks, a license and a few zealous traders who want to have better sales results much too much.

The pain of waiting for court decision

The entrepreneur from the electronics industry said: “The Central Anti-Corruption Bureau (CBA) have questioned me on the VAT scams. They wanted to know who had managed the business. I just laughed: ‘If someone managed it, even you wouldn’t find it out‘. My case of tax authorities blocking 120 million zlotys of VAT has been in the tax office for five years. The tax office blocks the money, just ignoring judgments passed by the Voivodeship Administrative Court (WSA.

These days, a tax assessment notice can be issued on any company, and it takes five years to obtain a decision saying whether or not it was well founded.”

Clues on Castor lead to Dubai. We know this not only from Skarin, but also from a source who has knowledge on an investigation on the Norwegian carousel conducted by the FBI. American investigators were to question a Danish citizen living in the United States on that matter. People responsible for money laundering in Oslo and the carousel in Poland have links to the same circles, says the source interviewed by our colleagues from Dagbladet Information.

For the time being, the FBI have not confirmed this information, giving confidentiality of investigation as an excuse.

The public prosecutor’s office in Katowice has had more to say than the American investigators. It has sent us a statement: it is conducting an investigation against eight individuals. Except L., another person whose identity we have not identified is staying in custody.

L. pleads not guilty. He claims that his only duty at the energy companies was to acquire customers.

Which he actually handled pretty well.

Strings of emission mafia leads to Slovakia

This is Polish angle of the story. But how VAT mafia was developed in Slovakia?

Journalists from aktuality.sk discovered, that the company with enormous income ended up with tax debt over hundred million euro and was probably a part of international tax fraud scheme. Case is already under police investigation.

Mysterious company Clean Energy Trade (CET) has no employees, but ended up between Slovak companies with highest income in 2014. With over a billion, it surpassed all banks, all retail companies except one, and all companies in energy sector except two.

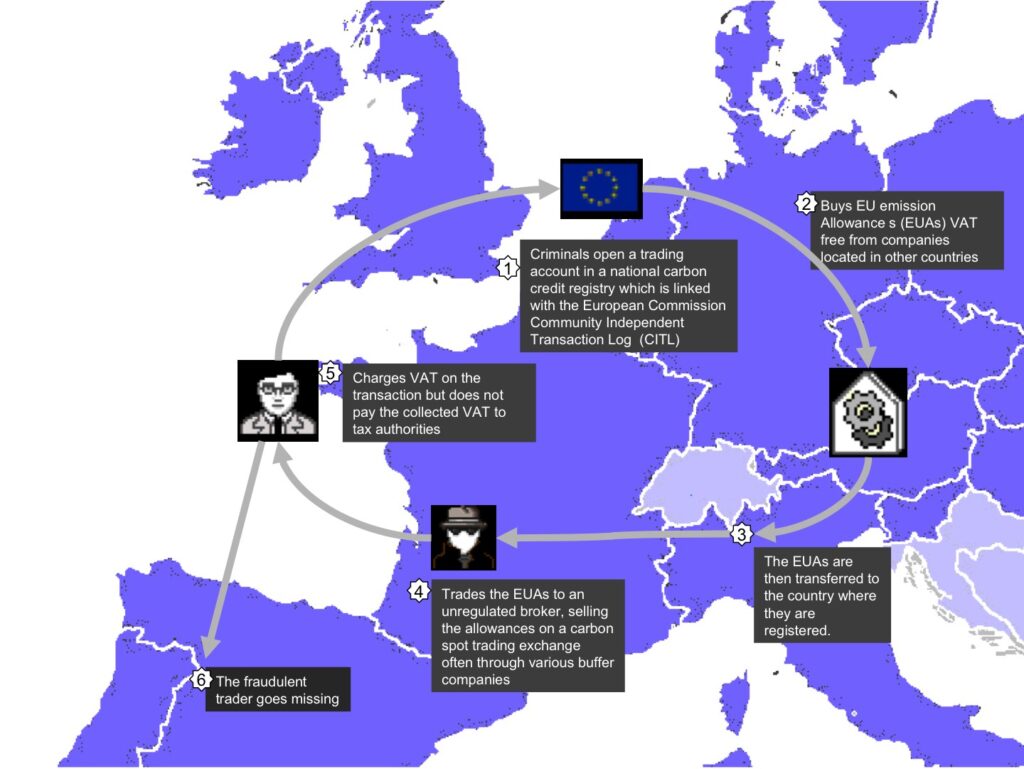

Journalistic investigation uncovered that company has been involved in carousel tax fraud (according to official documents). Reports show, that Italian investigators from Guarda di Finanza considered Clean Energy Trade to be a part of a fraudulent scheme involving trading with emission permits.

CET’s business model consisted of emissions trading – selling emission permits, also called emission allowances. These allow states, or particular companies, to emit certain amount of emissions, especially green house gases.

CET’s position in the tax fraud scheme was called “buffer” – in other words a company in the middle of the scheme buying and outright selling the permits for the sole purpose of making the chain of trades more complicated and difficult to uncover and investigate.

CET was managed by French national Jean Pierre Rogué, who also had a stake in other shell company in Italy – Trading partners. It was Trading partners, which was supposed to buy emission permits from CET during 2010 and 2011.

Except this Italian company, dozens of others from all over Europe have taken part in the scheme.

Web of companies created by fraudsters was partially unraveled by investigators from Italy, Germany, or Great Britain. Key person involved in the fraud was, according to the investigators, Imran Yakub Ahmed from Great Britain.

Ahmed is now living in Dubai despite pending arrest warrants for him. United Arab Emirates refuse to extradite him. UAE was also supposed to be the place for “emission parties”, where fictitious businesses were negotiated.

Since the web involved hundreds of companies, persons and thousands of trades, it is extremely difficult to quantify combined damages. It remains clear, that beneficiaries benefited with hundreds of millions of euros, that are now missing in member state treasuries.

CET cleared a record profit in 2013 – 158 million euro. A year later, tax inspectors were unable to contact the firm. It’s tax debt started rising all the way up to 135 million euro. At that point, CET was associated with probable fraudulent operations.

Tax bureau does not wish to issue any statement concerning this case: “Due to tax secrecy we cannot comment on particular company’s tax affairs. In accordance with the law, tax secrecy is any information about a a tax entity, obtained by tax bureau” responded spokesperson Ivana Skokanová.

The police confirmed, that investigator started prosecution in this case of tax fraud.

“Business cases took part in six countries according to current findings. At this point, prediction of length of investigation is not possible due to waiting for international legal aid,” specified police’s spokesperson Denisa Baloghová for Aktuality.sk

Europol uncovered similar fraud scheme with emission permits labeled “Carbon credit fraud” in 2009. Europol quantified damages to 5 billion euro.

Despite efforts to prevent such fraud, similar practices continued even years after the scandal – perpetrators being different criminal groups.

In case of emission trading, most of EU member states introduced so-called “reverse-charge” system, when value added tax is paid by a buyer instead of a supplier. Thanks to this system, carousel tax frauds with emissions have been almost eliminated by now.

VAT Tax fraud is, however, still a phenomenon. It is continued by trading different commodities – especially energy, fuels, metals or mobile data. Marketing and advertising services are also risky, like other services, volume of which is difficult to control.

Hungarian companies also involved in “Grand Theft Europe”

In April 2010, around noon on a Wednesday, four policemen were standing in front a tower block in the outskirts of Budapest. They came to search the home of a professional boxer who lived on the tenth floor. The police searched the flat in an hour and seized two computers.

The Hungarian police conducted the search based on information they had received from the German authorities. According to the Frankfurt Prosecutor’s Office, the boxer was involved in the activities of a Hungarian company, which was a member of a VAT fraud network. The fraudsters – including employees of the largest German bank, Deutsche Bank – operated in several European countries in 2009 and 2010 and defrauded 800 million euros.

According to German authorities, a Hungarian company Clean Power Solution Kft. also participated in a VAT carousel network connected to Germany, mentioned above. More recently, the owner of another Hungarian company, Hydro-Well Kft., was accused by the Czech authorities of being a member of a network that supplied fuel to the Czech Republic from Slovakia. However, Czech members of the network failed to pay VAT, causing over 8 million euros of damage.

In response to Direkt36’s questions about carousel fraud, the Hungarian Ministry of Finance quoted the government’s measures to whiten the economy. According to the ministry, international cooperation is needed to address the problem at the European level.

The big carbon credit fraud

In recent years, criminal organizations used goods that are not individually identifiable (such as crops, sugar and non-ferrous metals), products of high value but low weight that are easy to transport between countries (such as mobile phones, chips, electronic devices). Intangible products, such as intellectual rights and certificates, are also susceptible to fraud: they do not even need not be physically transported from one place to another, but their trade is subject to VAT. The so-called carbon credits, which belong to the latter category, became the victim of a series of fraud across several European countries, including Hungary, at the end of the 2000s.

The origins of trading with carbon credits goes back to the Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997, which aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The United Nations set the maximum amount of carbon emission for each country that signed the protocol. This is called CO2 quota, of which each country has a certain amount. Countries that plan to emit less carbon dioxide than their quotas would allow, can sell their quotas to countries that pollute more.

In addition, it is also possible to obtain more quotas in exchange for various green investments, such as the installation of wind farms and solar power plants. One carbon credit is given after every ton of saved CO2 emission. Carbon credits can be traded also by companies and individuals.

For years, this has also provided an opportunity for carousel fraud: the credit buyer sells carbon credits from one EU country to another, VAT-free. The buyer, however, sells it on at a gross price but disappears before paying VAT into the budget. Typically, such missing traders only exist for a few weeks or months and their executives cannot be reached through the contact details of the company.

In 2009 and 2010, a carousel fraud network earned 800 million euros (more than 200 billion forints) from fraud with carbon credits. The credits were sold to various missing traders that failed to pay VAT, while the final buyer was Deutsche Bank. The German authorities have indicted nearly 200 people. In June 2016, the court found six employees of Deutsche Bank guilty (only one banker was imprisoned, the rest received a suspended prison sentence).

Confidential documents about the investigation into the CO2 carousel fraud network were shared by the German CORRECTIV with journalists working on the Grand Theft Europe project. According to these documents, a Hungarian professional boxer was also suspected of having been involved in the network. The boxer was the agent of F. Mohammed, the British owner of Clean Power Solution Kft., registered in Budapest. The Hungarian boxer’s role was to forward the company’s documents to the owner who was living abroad.

“I got to know Moha on a boxing gala in Hungary, everyone called him like that. As I recall, we were sitting side by side. He asked me if I could do a favour for him and forward him the letters of his Hungarian company. I didn’t know, and I also didn’t care about what the company was doing. Finally, I caught heat for this. After the house search, I broke all contact with them,” the man told Direkt36. He said he didn’t know he was named as a suspect in the case. “My flat was searched by the police, I gave them the laptops they asked for, but nothing else happened since then,” he said. Direkt36 does not reveal the man’s name because Hungarian law does not permit to identify people involved in criminal inquiries unless they have already been convicted in court.

Founded in March 2009, Clean Power Solution sold carbon credits – a total of 5.2 million tones in half a year – to a number of companies registered in Munich, the Frankfurt General Prosecutor’s Office wrote in April 2010 in a letter to the Metropolitan Prosecutor’s Office, asking the Hungarian authorities to co-operate on the case.

According to the Frankfurt Prosecutor’s Office, the Hungarian company’s customers were typical missing traders: they did not pay VAT in Germany, resulting in a loss of at least 16.8 million euros. In the end, carbon credits were acquired by Deutsche Bank through several other companies.

Meanwhile, Clean Power Solution Kft. did not even have its own office. It contracted two companies to offer registered office services, who were also entrusted with receiving mail addressed to the company.

In April 2010, the Hungarian authorities did not only search the boxer’s flat, but also the offices of these companies offering office services. One receptionist told the Hungarian police that Clean Power Solutions had only received “one or two letters,” which were then forwarded to an address in Glasgow, provided by the company. However, the letters returned unopened. Since Clean Power Solution did not pay the bills for the provision of office services, both providers terminated the contract with them.

Clean Power came under liquidation proceedings in 2011. At that time, it owned 420 thousand forints (over 1000 euros) to the Hungarian tax authority. F. Mohammed, however, did not get in touch with the liquidator, so the company was deleted from the business registry in 2014, without ever having paid its debts.

Fuel business through Hungary

At least one other Hungarian company was involved in another network.

Last December, the Slovakian Aktuality.sk portal published a detailed article on the dubious businesses of a family that accumulated huge wealth in southern Slovakia.

The Kolozsi family lives in Zsigárd, fifty kilometres from the Hungarian border. On their estate called Kolozsi Ranch, the family organizes an annual international coach driving competition, where Hungarian musicians regularly perform.

The companies belonging to the Kolozsi family have been – at least, on paper – producing ten million euros of income for years, but only modest profit has been reported. According to Aktuality.sk, one of the companies of János Kolozsi traded diesel fuel with a company named Jopi Trade, registered in the neighbouring Vágfarkas – except that this was done in a fictitious manner. During an inspection, the traders were unable to present transportation documents.

János Kolozsi told Direkt36 over the phone that the Slovakian newspaper lied about him. According to Kolozsi, after the publication of the articles, the tax authority carried out an inspection at his companies, and they found “everything in order”.

According to the Czech authorities, Jopi Trade also appeared in a Slovak-Czech carousel fraud network. According to documents published by the Czech tax office in 2016, fuel from Slovnaft, a Slovakian subsidiary of Mol, was bought by Jopi Trade through a British company. Jopi then sold it – through several companies – to a company called FAU in the Czech Republic. Although the goods were passed through several companies on paper, the shipment from Slovnaft was actually transferred directly to the FAU’s storage facilities. Companies in the chain that would have had to pay VAT disappeared, causing a total tax loss of 8,4 million euros for the Czech state.

According to the investigation carried out by the Czech tax office, the Hungarian Hydro-Well Kft. was also involved in the network and was in contact both with Jopi and János Kolozsi. Founded in 2011 in Győr, the company also had a branch office in Komárom from 2013, right next to the Slovak-Hungarian border. Until 2016, the company was owned by a woman from Győr who never had any other business interests.

According to the Czech tax office, Hydro-Well entered the tax evasion network through Jopi Trade, while János Kolozsi helped the Hungarian owner to keep in touch with business partners. The Czech tax office also contacted the Hungarian woman during the investigation. It concluded that she “only met the business partners personally when they signed contracts,” but maintained a regular business relationship with Jopi and the Kolozsi family.

Direkt36 contacted the Hungarian woman through Hydro-Well, where she is still listed as the agent of a new owner living abroad, but she did not answer the e-mail. János Kolozsi said that his name appeared in the Czech documents “by accident”, and he did not help the Hungarian woman in any way. Kolozsi confirmed that he wanted to do business with Hydro-Well, but “this didn’t work out, as the price was not right”.

In 2013, the Hungarian company was one of those businesses that supplied fuel to missing traders in the Czech Republic. In that year, the company reported 10.4 billion forints (over 30 million euros) in revenues, while it posted a loss of 141 million forints (over 400 thousand euros).

According to the Czech authorities, FAU “could have or should have known” about the fraud, so they froze FAU’s accounts and the company went bankrupt. However, the Czech court later ruled that the penalty was unlawful. The Czech press speculated that the case could have been politically motivated: FAU was a business rival of current Czech Prime Minister Andrei Babis. On a leaked voice recording, Babis said that his “guys” put pressure on FAU.

Hope in unity

Cross-border VAT fraud is as old as the current VAT system of the European Union, which was introduced in 1993, only as a temporary solution. While the system has repeatedly been modified over the past 25 years, these reforms do not provide sufficient protection against VAT fraud.

In 2017, the European Commission proposed a series of fundamental principles and key reforms to the EU’s VAT system towards a “Single VAT Area”. In the proposed system, as a general rule, the seller would be responsible for charging and collecting the VAT in the case of an intra-EU supply, irrespective of the place of residence of the consumer.

The new system, planned to be introduced in 2022, is estimated to reduce the damage arising from cross-border VAT fraud by eighty percent. However, the adoption of the proposal requires unanimous decision and the new system would greatly build on trust between the tax authorities of different member states.

Until a comprehensive reform at EU level, the member states themselves are introducing new regulations against cross-border VAT fraud. For example, in 2015 Hungary launched the Electronic Public Road Trade Control System, which enables the tax authority to track the goods that are transported in the country. Companies that transport products between Hungary and any other EU member state are required to register in the system, and submit the details of each delivery, such as the name and the quantity of the products transported.

In addition, as of July 1, 2018, all companies must send the tax authorities a copy of their invoices containing VAT higher than 100,000 forints.

“The measures aimed at whitening the economy (…) give a more detailed insight into companies’ activities: they reveal suspicious transactions and also help risks analysts of the tax authority to spot so-called missing traders,” Norbert Izer, Minister of State for Taxation told newswire MTI in April.

For Grand Theft Europe, Direkt36, Fundacja Reporterów and Aktuality teamed up with a network of 35 European media partners from every European country, coordinated by the German non-profit newsroom CORRECTIV. Together the network is investigating VAT carousels, the biggest ongoing tax fraud in the EU. The investigation has resulted in numerous stories, a podcast and a number of TV documentaries. The project: www.grand-theft-europe.com. For the Hungarian company data, the services of Opten were used.

Anna Kiedrzynek is a journalist for the Polish edition of Newsweek. She also wrote for leading Polish daily newspapers, e.g. Gazeta Wyborcza and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Anna gained valuable experience while participating in The Gabriel García Márquez Fellowship in Cultural Journalism in Colombia. Anna’s professional interests lie in human rights, migration, American politics, poverty and social exclusion.

Blanka Zöldi is a reporter with Direkt36, a non-profit investigative journalism centre in Budapest. Most recently she has been covering the misuse of EU funds and the Golden Visa program in Hungary.

Peter Sabo is investigative reporter of Aktuality.sk. He is uncovering corruption using mostly data-driven approach. He was wroking in IT sector as analyst before joining Aktuality.