“Matt, the screening is only about a third full. If it’s not at least half, you can pack your bags on Monday,” jokes Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) director Drew Sullivan. “Please, can you stop doing that and not just look at the numbers all the time? I don’t want to know,” director Matt Sarnecki fumes, walking outside the hotel for a smoke. There is one day left until the premiere of The Killing of a Journalist at Hot Docs, North America’s largest documentary film festival, in Toronto.

We flew to Toronto in late April for the premiere of this film documenting the murder of Slovak journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Compared to other big production companies, our team was small, consisting of only a few people: the film’s director, Matt; the two directors of OCCRP, Drew Sullivan and Paul Radu; the film’s main producer, Signe Byrge Sørensen from Final Cut for Real; and Pavla Holcová and Eva Kubániová from investigace.cz.

What is the documentary The Killing of a Journalist about?

The documentary The Killing of a Journalist decribes in detail not only the murder of Slovak journalist Ján Kuciak and his girlfriend, Martina Kušnírová, but also the dramatic events in Slovakia that followed this horrendous crime, which exposed corruption in politics, the police, the judiciary, and big business in Slovakia. An important moment in the film comes when reporter Pavla Holcová receives a copy of the police file from an anonymous source. She then works together with a number of Slovak journalists to create the “Kočner Library.” The world premiere took place on May 1 in Toronto at the Hot Docs International Film Festival. The European premiere will be announced soon.

Our small group is wet and cold on the way to the Varsity multiplex, one of the festival’s screening places. Spring in Canada doesn’t care if you’re going to a big premiere or not; the weather is the weather. Standing in a cocktail dress in a huge shopping mall also feels strange. Instead of a red carpet, we take the escalator to the top floor, where the cinema is located. This major film festival doesn’t resonate with Toronto’s three million people so much. The rush of a big city lives its own way.

We stand tensely in a circle, each of us pretending not to be nervous. Every now and then, someone glances at their watch to see if it is time to go into the cinema. I ask Matt how he feels, but he turns around and says he’s going to buy a book. In some ways, it’s an advantage to go to a screening in a shopping mall.

“I’m so nervous. As always before a premiere. The last ten minutes are the worst. There’s no rational basis for it at all, but I’m worried that, for example, the subtitles won’t appear or something will happen to the film,” Signe muses aloud, even though she has experienced dozens of similar film premieres.

Drew checks the number of available seats again. “More than half are filled. There are about five hundred seats,” he says. “How do you know how many seats there are? Don’t tell me you counted,” I ask, and we all start laughing. The OCCRP director nods and heads to the popcorn and Coke stand. He’s American, after all, and you don’t go to the movies here without popcorn.

“To be honest, I’m not nervous at all. I’m more excited to finally see the film on the big screen. I’ve never seen it like this before, especially with proper sound. On the other hand, I admit that I am a little nervous. I’m afraid people won’t like it,” Matt says after returning from the bookstore, clutching the latest bestseller recommended by The Washington Post.

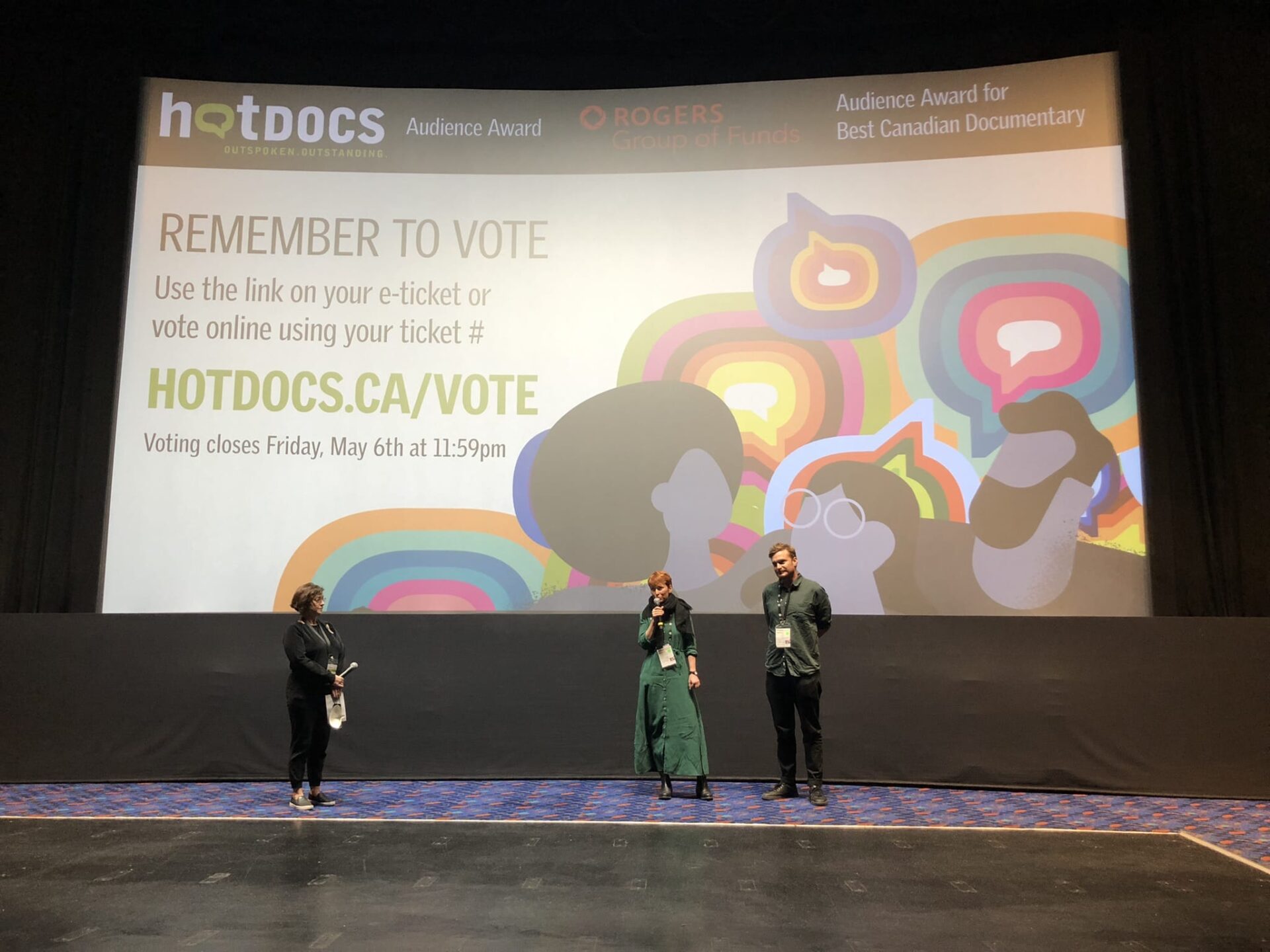

The premiere of The Killing of a Journalist at Hot Docs. Source: Eva Kubaniova

At 5 p.m., we finally start. Director Matt Sarnecki steps in front of a room two-thirds full and talks about how he worked on the film for more than two years, as well as thanking the audience for their interest and his filmmaking team in Europe. “I hope you enjoy the film and stay for a short discussion after the film. We have brought a special guest from Europe,” he says, ending his opening speech. The special guest is sitting next to me in a green dress, the same dress she is wearing in one of the documentary’s key scenes.

“The best film I’ve ever seen in my life”

The film is running, and we’re watching the audience and their reactions. I’m gripped by a fear that none of us have ever spoken of before. What if people in Canada don’t get it? After all, the story unfolding before their eyes is so distant and surreal, why should they believe it? Just like we didn’t believe it when it actually happened.

In the first few minutes of the screening, people shake their heads, cover their faces, or just sigh softly. I expected all these reactions. But then they start laughing. Laughing? Yes. Former prime minister Robert Fico and that particular press conference are laughable. They get it. They get it more than we thought.

Shooting of the documentary The Killing of a Journalist. Source: Eva Kubániová

The audience seems captivated for the entire two-hour screening. Our concerns about whether the documentary was too long and complicated are forgotten when the crowd breaks into a massive round of applause. They loved it! The audience begins clapping as the credits start to roll. This visibly takes the fear and nervousness out of our European group.

Next on the program is the Q&A session, and the announced mystery guest is making her way in front of the big screen. The first question from the audience is whether she knows the source who gave us the police file, to which Pavla Holcová answers, “Yes.” Silence reigns in the screening room, neither the moderator nor the audience know yet that Pavla is famous for giving brief answers. They quickly get used to it, however, when the next two questions are followed by one-word answers. The audience laughs, and it is clear that they like Pavla’s style.

“It was the best film I’ve ever seen in my life. Thank you very much,” one viewer tells us. We are delighted. The other reactions were similarly positive. When we leave the cinema, people thank us for our work and congratulate us. It’s a strange feeling that journalists are not used to.

“I feel a huge relief; the audience was very focused. For example, the fact that they laughed at the right moments is also important. There are passages in the film where people say something, but we can read something completely different from their faces. I think the audience understood exactly what we wanted to show them,” sums up the satisfied producer Signe.

We take one last photo with the Hot Docs festival poster and head out in the rain to celebrate. In a pub, where fans are noisily enjoying the NHL playoffs, our group stands out among the hockey fans in their jerseys.

Over a beer, Matt confides that this is his second film about a murdered journalist and it might be enough.

“Emotionally, it’s terribly draining. I don’t want to be the one my colleagues call when another journalist dies. And I certainly don’t want other journalists to be killed. But anyway, it’s a huge relief to me that we’ve made it this far. Thank you all,” Matt says, describing his feelings, before he makes a toast and personally thanks everyone.

The following morning, we get news from “distant” Slovakia. “Marek Para has been taken into custody,” I say to Pavla as we wake up and I read a report about the well-known lawyer, who defended Marian Kočner, being charged with working on behalf of a criminal group revolving around oligarch Norbert Bödör. “What? I guess we will have to keep changing the updates at the end of Matt’s movie every month,” Pavla laughs, and we pass the message to our colleagues in our small Toronto chat group.

Eva is a journalist working for investigace.cz based in Prague. Investigace.cz is NGO covering organized crime topics and the only Czech partner of OCCRP. She works on projects connected to Slovakia.