A ’bad boys’ band in the European Union; a playing field for politicians eroding young democracies; or one of the most emerging points on a map of global competition between the US and China: what is V4 really about today?

It was the summer of 2017 when we met once again to discuss the shape of our cross-border investigative collaboration in the Visegrad region. Walking during a warm Warsaw evening with our friends: journalists from Hungary, Czechia and Slovakia, we discussed first of all the ongoing massive demonstrations against judiciary reforms that were announced and then rapidly passed through the Polish parliament by the Law and Justice.

“How did we end up here, just 28 years after the democratic transformation?”

I found it challenging to explain to our colleagues.

“It is still just the beginning,” warned my friend from Budapest.

She sounded so firm and had no doubts. I remember her sobering words well.

At that time, huge demonstrations in solidarity with the Central European University that Victor Orban wanted to force out of Budapest had already passed. It was the seventh year since Orban took complete power over Hungary, and was consistently implementing his version of “illiberal democracy”, taking control of the last remaining independent media and effectively playing games with Brussels, to reshape the meaning of the EU solidarity.

Orban’s success was something Jaroslaw Kaczynski had always struggled to achieve, until now, when it has eventually turned out to be attainable-at least to some extent.

Just after being defeated again in 2011 elections, Kaczynski referring to the case of Orban, who took power after eight years in the opposition – declared: “I am deeply convinced that a day will come when we will have Budapest in Warsaw. Sooner or later we will win, because we are simply right.”

The day of his victory indeed came 4 years later, yet neither then nor in the latest elections in the fall of 2019 Law and Justice were unable to win a constitutional majority, so Kaczynski couldn’t force all the reforms that he planned as easily as Orban did.

For us, the conversations we had in summer 2017 were fundamental for our understanding of hidden layers of the Visegrad region today: of the old issues and upcoming new processes and threats.

“Is there any current common identity of our countries except the word “goulash” in each language?”, we asked ourselves, adding, “apart from the history?”

“The years of similar destinies and struggles for similar ideals ought therefore to be assessed in the light of genuine friendship and mutual respect; that is, precisely in the spirit that dominated the years during which secret independent literature was smuggled in rucksacks across our common mountain ranges” – as Vaclav Havel described in his speech in the Polish Parliament at the beginning of 1990.

What are the areas we should examine to see what has still been unrevealed? What should we pay special attention to? Every discussion brought new points to the list of common issues: from growing Russian propaganda and influence, to domestic disinformation campaigns and polarisation, to Chinese influence and investments in the infrastructure in the region, to exporting Orbanism to all the V4 countries (including hate campaigns against migrants, Soros, and LGBT).

So we started to dig into it more, then published a number of cross-border stories covering the four Visegrad countries on vsquare.org, launched in October 2017.

Read more: Three years of VSquare

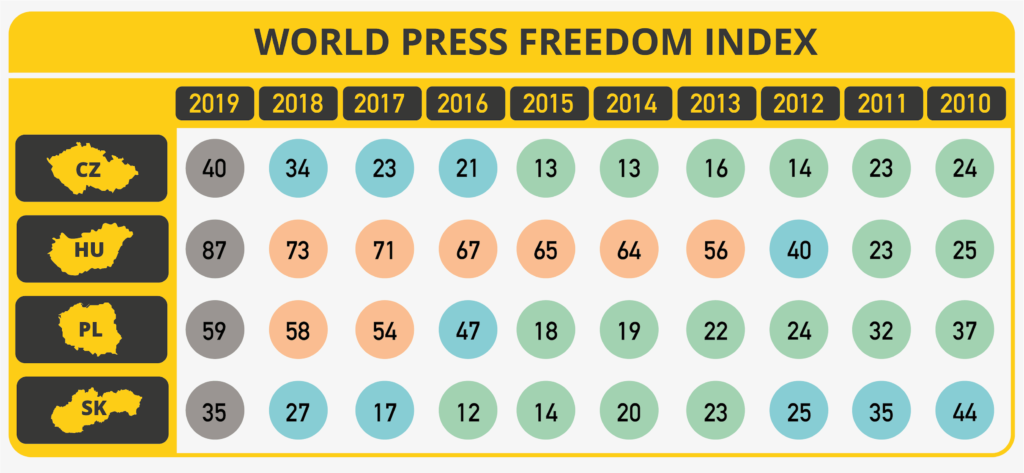

In the next 3 years we have been experiencing and explaining the rapidly changing political and media landscape in Poland, Hungary, Czechia and Slovakia. The level of press freedom has significantly declined every year, in a not-so-surprisingly similar manner. In 2018, all four countries had fallen in the RSF Index.

In the Czech Republic, president Milos Zeman presented himself with a “kalasnikov for journalists” and a prime minister Andrej Babis (elected in October 2017) attacked independent reporters as “fake news makers”, when being himself an owner of influential newspapers. (RSF: 34th position in 2018, -11 to 2017).

The Polish ruling party Law and Justice continued their aims of “making the media Polish again” and completing Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s wish. Public media was transformed into a pro-government propaganda machine, spreading hate speech and heating up polarisation in society. (RSF: 58th position in 2018, -4 to 2017).

The last independent media outlets in Hungary (like Atlatszo, Direkt36 and index.hu) were left struggling to survive, while Victor Orban constantly repeated: “There is a left-liberal anti-government media majority in Hungary today.”

In fact, the private media were already in the hands of oligarchs allied with Orban. (RSF: 73th position in 2018, -2 to 2017).

Graphics by Lenka Matoušková; data: RSF

In February 2018 we all froze in shock when we learnt that an investigative journalist Jan Kuciak and his fiancee Martina Kusnirova were murdered in Slovakia. Less than a month later, prime minister Robert Fico – who used to call journalists “filthy anti-Slovak prostitutes” and “idiotic hyenas” – resigned. Yet, the next year, Slovak journalists were told by Fico: “I have no respect for you, I do not fear you at all”. (RSF: 27th place in 2018, – 10 to 2017).

Pavla Holcova and Eva Kubaniova from our partner centre, Investigace.cz and OCCRP, were among the journalists who, from the very beginning, were the most engaged in finding the truth about the murder of their friend and collaborator. However, after two years following the trail, the Slovak court cleared Marian Kocner of ordering the murder (as the judges pointed out that the prosecutors have not collected enough evidence), and now the case will be examined by an appeal.

Whatever the decision will be, journalists will not stop asking questions and looking for the truth. Holcova, on behalf of OCCRP, just received the Slovak Journalism Award (Novinárska cena) for the Kočner Library project. To commemorate Jan Kuciak, the new Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak (ICJK) was launched in Bratislava at the beginning of 2019. Since the launch, we have welcomed it as our new partner for the cross-border collaboration.

Read more: Ján Kuciak story

We all crossed our fingers for Atlatszo – in late 2018, they revealed how the Hungarian government elite, including Orban, use a luxury yacht and a private jet registered abroad. After this outstanding investigation, Orban’s proxies organized a hate campaign against the journalists from our partner organization in their propaganda media.

In the last year in Poland, the journalists of Fundacja Reporterów revealed the operation “Lame Rebellion”, a result of an undercover investigation inside a Polish troll farm, operating at the backstage of politics and business.

Read more: The Operation ‘Lame Rebelion’

These are just a few examples of the stories revealing hidden layers of each country. In the last 3 years, together, we have published a number of cross-border stories revealing such hidden layers between our countries. And we know that there is still so much to discover.

Some new element is brought to these puzzles almost every day. Like the last announcement by the Hungarian and Polish foreign ministers, who said they are going to establish a new Institute for Comparative Law against the “suppression of opinions by liberal ideology”, that would examine whether the two countries are not treated under “Brussels double standards”. This plan is seen by the UE as a sign of further escalation in terms of the rule of law.

Whereas such a cooperation among mainstream politicians in V4 is striking, as it turns out there is also an ongoing collaboration between the alt-right. The latest example has come with Polish and Slovak politicians fighting together against the pandemic (and masks). Grzegorz Braun, MP of the nationalist party Konfederacja, invited the two MPS from neofascist People’s Party Our Slovakia, Milan Uhrlik and Milan Mazurek, for a demonstration in Warsaw. Uhrik gave a speech during the protest.

Three years since launching vsquare.org, we repeatedly go back to the question: what is the key issue now? A battle line drawn against the UE on migration? Reforms of the judiciary and the rule of law? Belarus (with different approaches within V4)? 5G and the influence of China? Russian disinformation campaigns and domestic propaganda?

In a short perspective, how the governments of V4 will handle the second wave of the pandemic, and how it will affect the region in a long perspective?

Is the Visegrad group more a ‘bad boys’ band in the EU; a lab for populism; a playing field for politicians who are eroding young democracies – or is it first of all one of the most emerging points on a map of global competition between the US and China?

Whether it is all of these and more, still needs to be revealed and explained. Undoubtedly, this is a fascinating region to follow.

Anna Gielewska is co-founder and editor-in-chief of VSquare and co-founder of Polish investigative outlet FRONTSTORY.PL. She is also vice-chairwoman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). A journalist specializing in investigating organized disinformation and propaganda, Gielewska was the John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2019/20) and has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2015, 2021, 2022) and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Award (2021, 2023). She was the recipient of the Novinarska Cena in 2022.