Slovak oligarchs are hiding their assets in complicated schemes that use lawyers as nominee owners. The Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak has proof that these lawyers act as the real owners’ proxies and that, in at least one case, such a scheme was utilized for money laundering. A proxy lawyer also served to hide an oligarch’s ownership of an influential Slovak newspaper and might connect this wealthy businessman to one of the biggest gas traders in the country.

Having nominee directors and nominee shareholders is not a legal practice in Slovakia. However, that does not mean it is not commonly used to cover up the real ownership of companies, especially if they are involved in money laundering schemes. In Slovakia, nominee owners, whose names are known to the public but who front for the real owners, are called “white horses.”

The Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak has uncovered the role of one such “white horse,” Martin Bahleda, in several schemes involving Jozef Brhel, an influential oligarch connected to the political party Smer-SD. Bahleda has admitted in at least one case, known in the media as the “Mýtink” case, who he was supposed to cover in one company, which is the key to exposing how money was laundered. It is one of the biggest scandals to come to light in Slovakia since the murder of Ján Kuciak.

Whenever Martin Bahleda’s name appears on any business’s official document, it is a strong signal that Jozef Brhel or his family is involved, too. Through this “white horse” is how we found out that the oligarch might have had influence over one of the major newspapers in Slovakia and that he had connections to one of the biggest gas companies in the country.

Toll collectors

When in 2021 the Slovak police conducted several raids connected to corruption, money laundering, and secret contracts at the Financial Administration – the government body responsible for taxes in Slovakia – they named the operation “Mýtnik,” the Slovak word for toll collector.

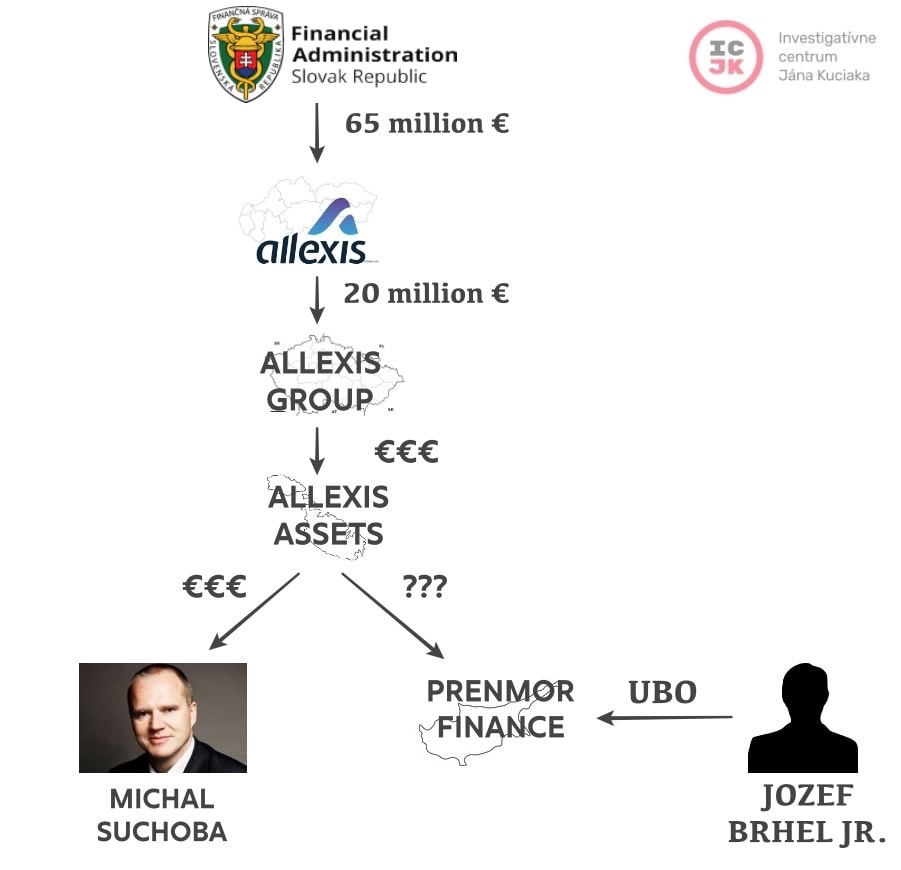

The story begins with agreements signed between the Financial Administration and Allexis, a private IT company in Slovakia. According to these contracts, which were kept secret at the time they were active, the Financial Administration paid Allexis over 65 million euros between 2014 and 2018.

Despite years of media scrutiny, due especially to the fact that the contracts were kept secret, it was not until January 2021 that law enforcement took action. For example, an anti-corruption NGO, the Stop Corruption Foundation, requested an audit of these contracts as early as 2017. In 2019, the Slovak Office for Public Procurement, an institution with the authority to investigate how state contracts are made, finished this audit and stated that these contracts had violated all the basic principles of public procurement required by law. According to the police, the IT solutions Allexis provided to the tax office were overpriced.

The Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak was able to trace where the money flowing out of the Slovak company Allexis ended up. We discovered two related companies: Allexis Group in the Czech Republic and Allexis Assets in Malta.

Half of the shares in the Maltese Allexis Assets were held by Michal Suchoba, the owner of the Slovak Allexis. The other half, however, were initially held by an unknown Slovak lawyer living in Prague, Martin Bahleda, from 2014 until 2016. Then the shares were transferred to another company, Prenmor Finance, established in Cyprus. The official owner of 100 percent of Prenmor’s shares was Martin Bahleda.

Based on the allegedly overpriced contracts, the Financial Administration paid the Slovak Allexis for IT services. From there the money could easily flow to the Czech Allexis Group, the Slovak Allexis’s mother company, which owned 100 percent of its shares. Although the Maltese Allexis Assets owned a smaller share in the Czech Allexis Group, this Maltese shell company owned the licenses for some of the products offered by the Slovak Allexis, likely the IT solutions that were supplied to the Slovak Financial Administration. Hence, the money paid by the Slovak tax authority ended up all the way in Malta.

From there, one half could go back to the official owner of Allexis, Michal Suchoba, and the other half to Martin Bahleda. However, Bahleda was not the actual beneficiary of the whole operation. He was there just to cover the person who really controlled things – an influential Slovak oligarch with ties to the previously governing Slovak political party Smer-SD, Jozef Brhel.

Admissions

After police raided Allexis and charged Michal Suchoba of being a member of an organized crime group and of violating duties when administering someone else’s property in 2021, he decided to admit his guilt and cooperate with law enforcement. He claims that Jozef Brhel blackmailed him – if Suchoba wanted to profit from any contracts with the Financial Administration, he had to share profits with the oligarch.

Based on Suchoba’s testimony, Jozef Brhel and his son, Jozef Brhel, Jr., introduced him to Martin Bahleda. The Slovak lawyer living in Prague. Suchoba claims that Bahleda was Brhel’s proxy, a “white horse.”

In 2013, Suchoba and Bahleda established several companies – the Czech Allexis Group, the Maltese Allexis Assets, and the Cypriot Prenmor Finance. They were now ready to launch their scheme and make millions off the Financial Administration.

In the end, profits from this corrupt business were, according to Suchoba’s testimony, shared between Suchoba and Brhel “fifty-fifty.”

Jozef Brhel, Sr., and Jozef Brhel, Jr., have also been charged in connection with the “Mýtnik” case, together with Suchoba. They deny any guilt. According to law enforcement, they were engaged in money laundering.

There is, however, no public evidence that the Brhels got any money from the scheme. The official ultimate beneficial owner of the companies was Martin Bahleda, not them. And there was no proof Bahleda was Brhel’s proxy besides the testimony of Michal Suchoba.

That is, until Martin Bahleda himself confirmed to the Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak that he owned shares in Prenmor, the company where half of the profits probably ended, whose real ultimate beneficial owner was Jozef Brhel, Jr. “I would like to state that I submitted all the documents to the law enforcement authorities without undue delay and provided them with cooperation. These documents show that Prenmor’s ultimate beneficial owner was and is Josef Brhel, Jr.,” wrote Martin Bahleda in an email response to questions sent by the Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak.

This is in line with what Jozef Brhel, Jr.’s lawyer Peter Rybánsky stated: “Within the scope of my knowledge and within the scope of my legal representation of the client, it is possible to confirm only that in all companies in which the client [Jozef Brhel, Jr.] was an ultimate beneficial owner, he was represented by JUDr. Bahleda in full compliance with applicable law.”

Source: ICJK

If it is true that Jozef Brhel, Jr., really was the ultimate beneficial owner of Prenmor Finance, the circle of money laundering in the case of Mýtnik is complete, as we now know exactly how the ill-gained money from the overpriced contracts at the Financial Administration flowed through shell companies to both final recipients of the money – Michal Suchoba and Jozef Brhel.

This also further proves that Michal Suchoba was telling the truth in his testimony, when he claimed Mr. Brhel requested to get half of the profits from this corrupt scheme, as Michal Suchoba and by extension Jozef Brhel’s son owned the final Allexis shell company fifty-fifty.

Newspaper owners

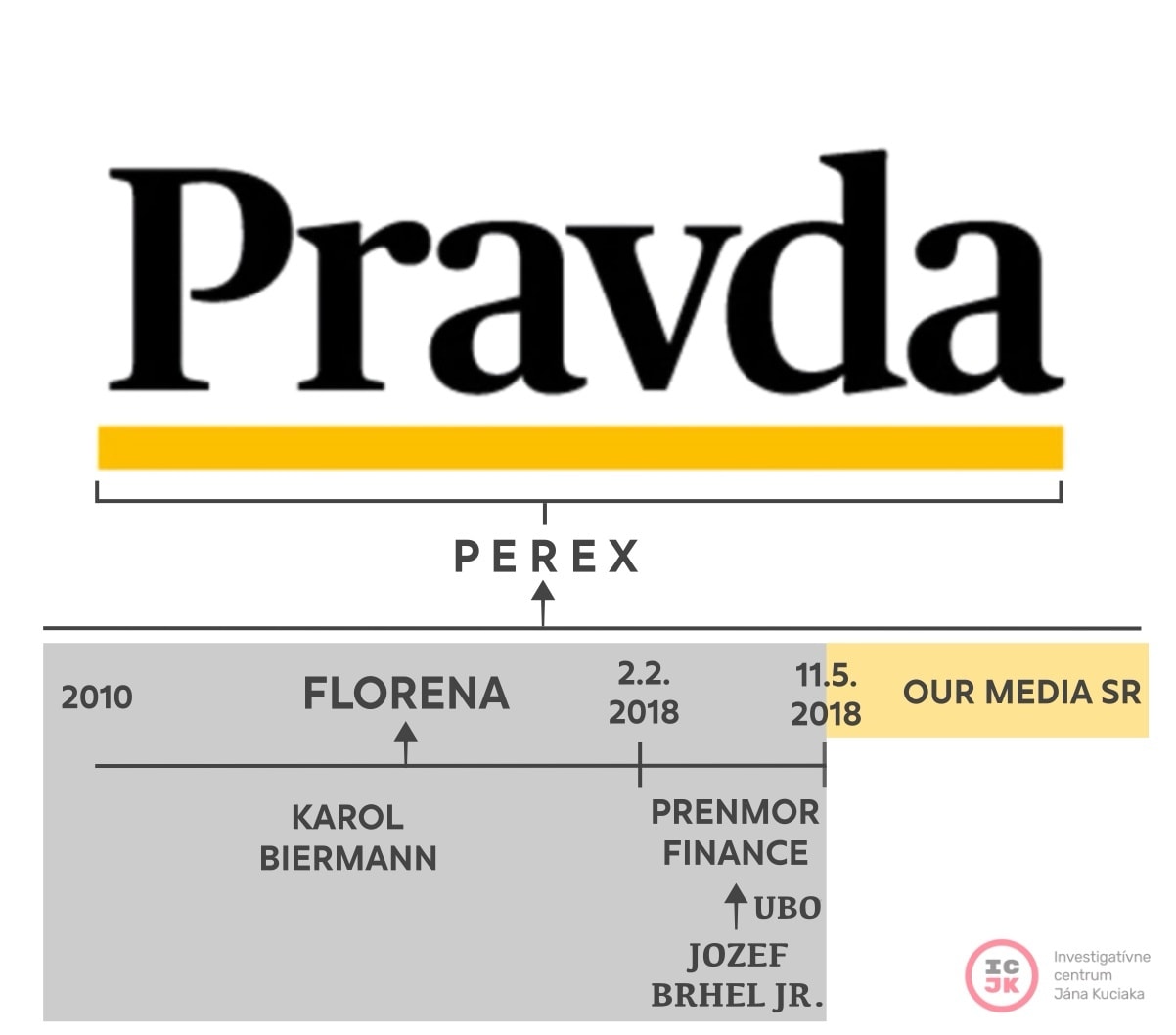

The Cypriot company Prenmor Finance not only plays a role in the money laundering scheme related to the Financial Administration and the Slovak branch of Allexis, but it was also involved in the 2018 sale of one of the most prominent Slovak newspapers, Pravda.

In 1990, PEREX became the owner of Pravda. In 2010, PEREX was purchased by the Czech company Florena. For years, Florena had only a single shareholder, Karol Biermann, the former head of Bratislava Airport during Robert Fico’s (Smer-SD) first government. Biermann was forced to resign after a scandal in 2008. (He attended a meeting in Monaco, on the yacht of one of the partners of controversial financial and investment group J&T. The meeting took place just days before the conversion rate of the Slovak crown, the official Slovak currency until January 1, 2009, and the Euro was announced. Knowing the conversion rate in advance might have provided significant benefits for the financial group.)

Florena owned PEREX and Pravda until 2018. In March 2018, Pravda published a report announcing that its new owner had become “the company OUR MEDIA SR a.s. Its 100% shareholder is the Czech company OUR MEDIA a.s., which is owned by businessman and senator Ivo Valenta together with media mogul Michal Voráček.”

The report also mentioned the daily’s previous owners: “The publishing house PEREX a.s., was until now controlled by Florena, a.s., which was wholly owned by the entrepreneur Karol Biermann.”

But that was not the case. According to the Czech Commercial Register, Karol Biermann no longer owned Florena at that time. On February 2, 2018, Prenmor Finance Ltd. became this company’s 100 percent shareholder. On the same day, Martin Bahleda replaced Karol Biermann on Florena’s board of directors.

At the time, Bahleda already owned 100 percent of the Cypriot shell company Prenmor. Today, however, he claims that the real owner was Jozef Brhel, Jr.

Source: ICJK

The sale of the PEREX and with it the daily Pravda was not finalized until May 11, 2018. That means Jozef Brhel, Jr., secretly owned one of the most widely read Slovak dailies for at least three months. But why would Karol Biermann sell Florena just months before the sale of Pravda was finalized?

Biermann asserts that he did not represent anyone else’s interests at Florena and owned it for himself, specifically denying a connection to Jozef Brhel. When we asked him if he was a proxy owner on Brhel’s behalf, he simply stated “no.”

He also claims that he has no relationship with Jozef Brhel and that he does not know Martin Bahleda. We also posed other questions to Biermann: If the sale of PEREX had already been agreed with OUR MEDIA, why did he sell Florena (together with PEREX) to Prenmor three months before the deal’s finalization? And when the sale of PEREX to OUR MEDIA took place, did OUR MEDIA pay Florena (already owned by Prenmor) or him?

“I will not comment on issues of a commercial nature. Thank you for your understanding,” Biermann replied to these questions.

OUR MEDIA claims to have negotiated the purchase with Biermann only; no one else was involved. “The whole transaction took place in a completely transparent manner and in accordance with all legal regulations. The only person we communicated with in this matter was Mr. Karol Biermann,” said OUR MEDIA spokeswoman Magda Pekařová.

However, she did not respond to our repeated questions as to which company or person OUR MEDIA paid for the purchase of PEREX and Pravda.

This information cannot be found in public sources either, as the Czech company Florena stopped submitting financial statements to the Commercial Register in 2016. The Cypriot company Prenmor Finance also does not have financial statements in any register.

Gas traders

In Slovakia, all companies that want to do any kind of business with the state must register in the Register of Public Sector Partners and disclose their ultimate beneficial owners, that is, their real owners.

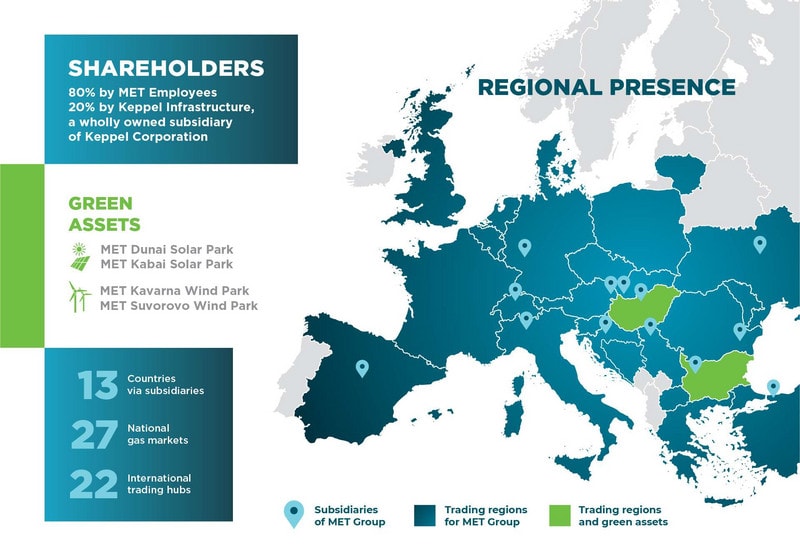

The case of MET Slovakia, one of the biggest natural gas suppliers in the country, demonstrates that companies have learned how to fool this register, too. Including false information in the register could result in severe penalties, such as the offending company being removed from the register, barring it from doing any kind of business with the state.

The official website of MET Slovakia states that more than 51 percent of its shares are owned by the Swiss company MET Holding AG. This conglomerate, with extensive activities throughout Europe, was founded several years ago by the Hungarian oil giant MOL, from which it takes its name – MOL Energy Trading (MET). MET Holding AG has been the subject of several scandals in Hungary involving Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, and suspicions of links to Russian energy circles have also emerged. The recent winner of the Hungarian parliamentary elections, Orbán, is a close friend of Oskar Világi, the head of Slovnaft, which also belongs to the MOL group.

Source: group.met.com

The remaining 49 percent of shares have officially been owned since 2014 by PEI Invest, an unknown Prague-based company. Today, the official owner of PEI Invest is an Irish lawyer, Conor Michael Delaney, who owns it via another company, Bluehill Investments. According to his profile on LinkedIn, he works for a Swiss company that provides services and managers to third-party companies. Simply put, his employer can cover up the real business owners.

Delaney confirmed in a telephone call that he works as a lawyer but refused to disclose who really owns MET. Between 2013 and November 2021, however, there was another lawyer involved in the corporate structures of PEI Invest: Martin Bahleda. For a short time, this proxy of oligarch Jozef Brhel also owned 100 percent of its shares.

Bahleda did not comment on his work at PEI Invest, and our questions were also not answered by lawyers and representatives of the Brhel family.

Our investigation of who currently owns MET Slovakia and PEI Invest points us toward another influential Slovak oligarch. The aforementioned Bluehill Investments also owns a stake in the Romanian brewery Csíki Sör. This British shell company’s share in the Romanian business indirectly suggests the involvement of a close friend of Viktor Orbán, Oszkár Világi.

Investigators from the Romanian branch of the Átlátszó portal pointed out the ties between Világi and the Csíki Sör brewery in 2017. They discovered that although András Lenárd has been the official owner of the brewery for a long time, half of the company belongs to two business entities – the Slovak company AZC and Bluehill Investments Limited – the same company which by extension owns Slovak gas trader MET Slovakia, officially owned by Irish lawyer Delaney.

AZC is owned by Slovak businessman Ján Sabol. This former state secretary of the Ministry of Economy is now one of the richest Slovaks – Forbes magazine estimates his assets at 100 million euros.

In 2017, the manager of several companies connected with Ján Sabol, Robert Spišák, tried to convince journalists that he was the co-owner of the Romanian brewery. However, in a recent telephone interview, Spišák admitted that at one point Bluehill Investments Limited belonged to the group around Sabol. Who owns it today, he could not tell.

In reality though, the aforementioned friend of Viktor Orbán, Oszkár Világi, was spotted in the brewery in the past. In 2017, journalists from Átlátszó published photos from an official visit to the brewery, which was also attended by Világi. He was casually dressed for the event, walking around in a polo shirt, shorts, and sandals.

Source: Facebook account of Mihály Varga

MET Slovakia, with unclear ownership and ties to oligarchs Brhel and Világi, continues to operate in Slovakia. According to the recent findings of the Investigative Centre of Ján Kuciak, several managers who used to work there, are now working for state-owned energy companies, nominees of the current government.

Cover illustration: YouTube, TV Markiza, Pravda, ICJK

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.