Hungary tops the list of countries for most OLAF recommendations for the recovery of EU funds between 2014 and 2018. In these four years, OLAF concluded 52 probes into misuse of funds and recommended that the EU Commission to recover 3.84 percent of payments made to Hungary under the bloc’s structural and independent funds and agriculture funds program.

Reacting to criticism from the European Parliament regarding the fraudulent use of the funds, Attorney General of Hungary Péter Polt insisted in 2018 that the country had launched investigations based on OLAF’s recommendations, disclosing a list of all such legal proceedings since 2012.

Atlatszo journalists researched these individual cases and found that some of them were originally reported by media outlets and investigative journalists, only later evolving into OLAF investigations and, afterwards, national criminal cases.

Most of the cases listed by the Attorney General are still open and ongoing. The charges revolve around similar themes, such as using fake expense certifications, inflating the price of equipment to be covered in public tenders. In some cases the applicants did not even have the intention to realize the venture and continued to mislead inspectors.

Early revealed, late investigated

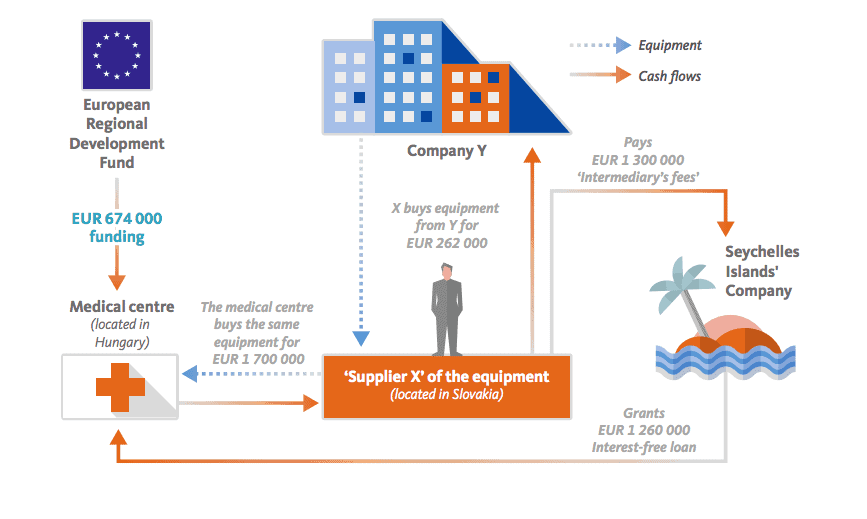

“OLAF opened an investigation based on a series of investigative journalism articles on EU funding for the construction and the equipping of a medical centre in Hungary,” OLAF’s 2014 annual report begins. It refers to a series of investigative articles Atlatszo published in 2012-2013, which revealed that a Hungarian company owning a medical center created a complex web of transactions in order to siphon off huge chunks of EU subsidies.

The OLAF investigation basically reiterated the investigative series’ main statement: the medical center claimed it had purchased equipment worth EUR 1,7 million, when in fact the supplier for the center had purchased the medical devices for only EUR 262,000 from a company in Slovakia. The supplier then paid EUR 1,3 million in ‘intermediary fees’ to a company registered in the Seychelles. The whole operation was aimed at quadrupling the declared prices of the medical devices and circumventing the EU obligation that the medical center provide a financial contribution of their own to the project.

The Hungarian fraud scheme as described by OLAF

Subsequent investigation by Hungarian authorities confirmed that the equipment bought with EU funds was overpriced and that the company employed naturopathic doctors instead of licensed clinical doctors. Based on OLAF’s recommendations, charges were pressed in Hungary and one of the defendants in the case was sentenced to prison in 2019.

No intention to use the funds

Another story that was made known publicly before OLAF or Hungarian authorities started taking measures, concerned funding for a dog welfare and rehabilitation program.

In 2013 OLAF notified Hungarian authorities about suspicious activities surrounding EU subsidies given to develop the program in the village of Drégelypalánk. Investigations followed, which prompted the Budapest High Prosecution Office to press charges two years later. The case had been publicly known for a long time, however.

In 2009 the Hungarian daily Népszabadság, which was shuttered by the Hungarian government in 2016, reported on the peculiarities surrounding the project. A 49-year old man, the first defendant in the trial, submitted an EU tender application in 2008 to develop a hydrotherapy treadmill to aid the physical rehabilitation of dogs. The application bid sought a 45 percent non-refundable compensation from a planned expenditure of HUF 250 million (692,000 euros). He received the first installment of the grant, but did not use the funds to implement the project, and according to the prosecutors, had never intended to do so.

Because the designated project headquarters didn’t have public utilities, and were unfit for the proposed activities, the prosecution concluded that the defendant sought to misappropriate the EU funds by issuing fictitious invoices and forging documents. The scheme involved a number of accomplices and the Budapest High Prosecution Office pressed charges on the grounds that the group attempted to carry out serious budgetary fraud, a crime that carryies a possible prison sentence of two to eight years.

Átlátszó learned that the appeals court found all of the defendants guilty. One of the defendants was sentenced to 1 year and 10 months of imprisonment along with 3 years of probation, while three others received fines ranging between HUF 150,000 and HUF 1.5 million.

In a similar case, a person was sentenced to 6 years in prison and received a fine of HUF 5 million for defrauding HUF 630 million (1,7 mln EUR) from the EU budget and HUF 140 million from the Hungarian state budget. In that case, a director of a company submitted EU tender bids between 2005 and 2010 for purchasing new machinery for producing paper bags without the intention of procuring the machines.

Subsidised and defrauded. Visegrad EU funds under the eye of OLAF

Hidden stories in OLAF annual reports

As a body that does not have the power to initiate national criminal proceedings, and is dependent on cooperation with relevant national authorities, OLAF does not usually publish its findings for individual cases. OLAF often uncovers cases that have not been disclosed by the member state authorities or by the parties involved.

OLAF does not name suspects in annual reports, but one can take an educated guess based on the details provided. Atlatszo identified one Hungarian fraud example highlighted in OLAF’s 2018 annual report in a subchapter entitled “Shell companies and fake business transactions”:

“In another case, OLAF received allegations concerning two closely related companies which had received European Regional Development Funds in order to implement two projects aimed at developing circular broadband networks in rural Hungary. The total value of the two projects, including the ERDF (European Regional Development Fund – VSquare note) grant and the contributions of the two companies was approximately EUR 12 million. OLAF investigators discovered that both beneficiaries subcontracted 100% of the works to the same general construction company. This contractor further subcontracted both jobs through a complex chain involving four layers. OLAF established that this complex chain was used to disguise the transfer of EUR 4.9 million back to one of the original beneficiaries in Hungary through a third party in another Member State. In this way, the two beneficiaries created artificial circumstances in order to increase the project value and to receive undue EU funding. OLAF recommended that the European Commission Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy recover the misused amount of roughly EUR 3.6 million. OLAF issued a judicial recommendation to the competent national authorities to initiate criminal proceedings.”

Although the report does not name the companies involved, it is specific enough to identify the case when using other public sources.

Highlighting ‘rural Hungary’ as a location clearly indicates that we had to look for regional broadband Internet development projects financed by ERDF grants. These projects are usually implemented by local telecommunications service providers offering internet access in their regions.

Grants awarded under similar programs in recent years have ranged from a few tens of millions HUF to the amount of 1-2 billion HUF. This significantly reduced the scope of our investigation. Two projects suspected of being fraudulent were clearly among the largest individual local broadband development grants.

As OLAF investigations take an average of one and a half years, and cases described in the yearly reports were most likely closed in 2018, we believe that the projects in question were covered by the Hungarian grant scheme GOP-3.1.2-12, from which grants were awarded in the years 2013-14.

In fact, according to the governmental database of EU-funded projects, there were only two projects worth more than one billion forints under this scheme. One supported the development of local broadband networks operated by Opticon Kft., headquartered in Kecskemét, owned by Béla Körmöczi (HUF 1.04 billion), and a similar project was a development by the affiliated company Optanet Kft. (HUF 1.67 billion).

Both broadband development projects were realized in Somogy County, and the two companies are indeed very closely related, since Optanet Kft.’s sole owner was Opticon Holding Group Zrt. between 2012 and 2016. Until 2012, owners of Opticon Holding Group Zrt. were Opticon Kft., Béla Körmöczi, and one of his sons.

Both companies merged into Vidékháló Kft. in 2016: the majority shareholder of this company is György Barna Csontos, a lawyer, who held a senior position at Opticon Kft. for years beforehand.

Opticon was a significant player in the rural internet market: the company cashed in a further total of HUF 767 million in three EU-funded projects in 2016. Since its merger with Optanet Kft., the successor company Vidékháló Kft. has been awarded a total of HUF 2 billion 42 million in EU subsidies in ten EU-funded projects.

However, the fate of the Opticon group took an unfavourable turn recently: in April 2019, 11 executives of the company were taken into custody on charges of fiscal fraud by the Criminal Directorate of the National Tax and Customs Authority.

There has been no public information on who the executives involved are, and what the nature of the alleged HUF 4.8 billion fraud was. However, company records indicate that the National Tax and Customs Authority registered the seizure of the shares of the Körmöczi family in Opticon Kft., and the shares of György Barna Csontos in Vidékháló Kft. in April 2019.

Atlatszo asked both companies and the National Tax and Customs Authority, whether there is an ongoing criminal investigation of the above-mentioned companies in connection with EU-funded broadband Internet development projects, but has not received a response.

István Tiborcz, Orban’s son-in-law, one of the 100 richest people of Hungary. Source: Facebook profile István Tiborcz

OLAF investigated the son-in-law of the Prime Minister

Former German MEP Ingeborg Grassle, who chaired the parliamentary committee overseeing the use of EU funds, warned in September 2019 that Hungary “has a problem with fraud, with corruption, with public tendering and with the fact that the justice system doesn’t want to deal with crimes, perhaps because there are people protecting the criminals there”. One of cases that is often mentioned in respect to these issues concerns Viktor Orban’s family.

At the beginning of 2018, OLAF sent the result of two years of its work to Hungarian authorities, recommending legal action over “serious irregularities” and a “conflict of interest” connected to Elios Zrt., a company that won contracts to install new street lights in towns across the country in 2011-2015. The 35 contracts investigated by OLAF are worth €40 million and were financed by EU funds.

During the time of these contracts, István Tiborcz, Orban’s son-in-law, co-owned and managed the company. Tiborcz is now one of the 100 richest people of Hungary, and at 33 years of age is also the youngest of the richest.

The company owned by Tiborcz has won many other public tenders that haven’t been scrutinized by OLAF. Elios worked for universities, stadiums, the state-owned electricity company, and a railway company as well. Atlatszo researched all public tenders won by Elios and found that 84 percent of the company’s public procurement income between 2010 and 2016 came from the European Union funds.

The details of how Elios operated to win the public lighting tenders were revealed in official letters sent by OLAF to the towns that had contracted Elios to install new street. Most of these letters became public after Atlatszo filed a freedom of information request with each municipality in question.

These documents make it clear how the public tenders were rigged: tendering criteria changed at the last minute, competing offers were written by the same person, the life cycle of the LED lamps was inflated, personal connections were revealed between the subcontractors and the auditing company, and in some places Elios was the sole bidder for the contract.

In February 2019, the Hungarian government decided not to submit invoices relating to Elios’ public lighting modernisation projects: in other words, no EU funds would be used to pay the company. Instead, Hungarian taxpayers are footing the bill. Transparency International Hungary said in a statement that “by this move the Hungarian government admits on the one hand the involvement of the Elios company in a seriously fraudulent tendering practice, while on the other hand acts as an accomplice by letting the suspected corrupt conduct go unsanctioned”.

This move means that OLAF no longer has any right to investigate the matter.

The Hungarian police has already closed down two investigations regarding Elios, citing a ’lack of crime committed.’ According to criminal law experts contacted by Atlatszo, the police should have concluded that what happened was a misappropriation of funds and state budget fraud committed by a criminal organization.

This text was financially supported by GACC (The Global Anti-Corruption Consortium) aimed at the Visegrad countries. Member centers Átlátszo and Direkt36 from Hungary, Fundacja Reporterów from Poland, Ján Kuciak Investigative Center from Slovakia and investigace.cz from the Czech Republic are working on the project.

An award-winning investigative journalist and editor, Tamás Bodoky is co-founder and director of atlatszo.hu. He is a Marshall Memorial Fellowship alumni and a member of several international investigative journalism networks. He is based in Budapest.