In the case of Latvia, where the people are heading to the polls this weekend, on October 6, the answer to the second question is “highly unlikely”, at least as far as social media are concerned. The Baltic Centre for Investigative Journalism, based in Riga Re:Baltica, has been monitoring platforms since summer. No persuasive evidence of foreign interference was found.

Then again, Russia hardly needs it. Heating up tensions at the EU’s and NATO’s Eastern border – which in recent decades has been one of the Kremlin’s aims – can be achieved more easily.

A quarter of Latvia’s little less than two million people belong to the Russian speaking minority. According to recent research, 82% of them watch Kremlin-controlled TV channels, which are freely available in the country. The Internet is polluted by seemingly independent news websites in Russian which, as our investigation this year showed, not only get their daily list of what to write about from the Kremlin-owned propaganda conglomerate Rossiya Segodnya, but are themselves owned by it.

To feed these sites, there is never a shortage of topics produced by local Moscow-financed “activists”, often reacting to the so-called Latvian parties.

A major source of outrage for the Kremlin-controlled sites is a right-of-center nationalist party (Nacionālā Apvienība), which, with the support of the other center and center-right parties, has pushed through parliament several initiatives which have infuriated local Russians. One allows dismissal of teachers and school principals if they are “disloyal” to the Latvian state, which Russian-language schools understandably interpreted as targeting them (Latvia finances education in minority languages.) Others will in effect ban Russian as a teaching language in the country’s secondary schools and universities.

These initiatives became the cornerstone for the campaign of the hardline, openly pro-Kremlin Latvian party Latvian Russian Union (Latvijas Krievu Savienība), a campaign that was surprisingly poor – both in terms of money and content – for a party that should naturally be one of Kremlin’s darlings. Apart from the Russian schools, another target of the campaign was the Latvian election commission’s ban on the candidacy of the LKS leader, MEP Tatjana Ždanoka. (Latvian law prevents communist party members who did not give up their membership after the country’s independence from running for office).

A third source of LKS support is events they generate by their own propaganda. When Latvian Security Police arrested one of the Kremlin-financed activists, Alexander Gaponenko, for spreading false rumors in social networks that Latvian authorities want to establish a concentration camp for Russians in the central stadium in Riga to please NATO, Russian-language media here portrayed him as a martyr. (This is not his first time behind bars for hate speech). And it works. When I interviewed the principal of a progressive Russian school in Riga, he was adamant (and angry) that the Security police are rounding up people who defend Russian schools. He had never heard the original charge on which Gaponenko was arrested.

LKS is currently lagging in polls, below the 5 percent level needed to get into parliament. Latvian parties have ignored Russian speakers for years, and they are turning to their only alternative, the pro-Russian party Harmony. For the last nine years, it has run Riga, the capital of Latvia, and it has burned Rigans’ money during this election campaign as if there is no tomorrow. (So far, it has been the biggest spender of all the contestants.)

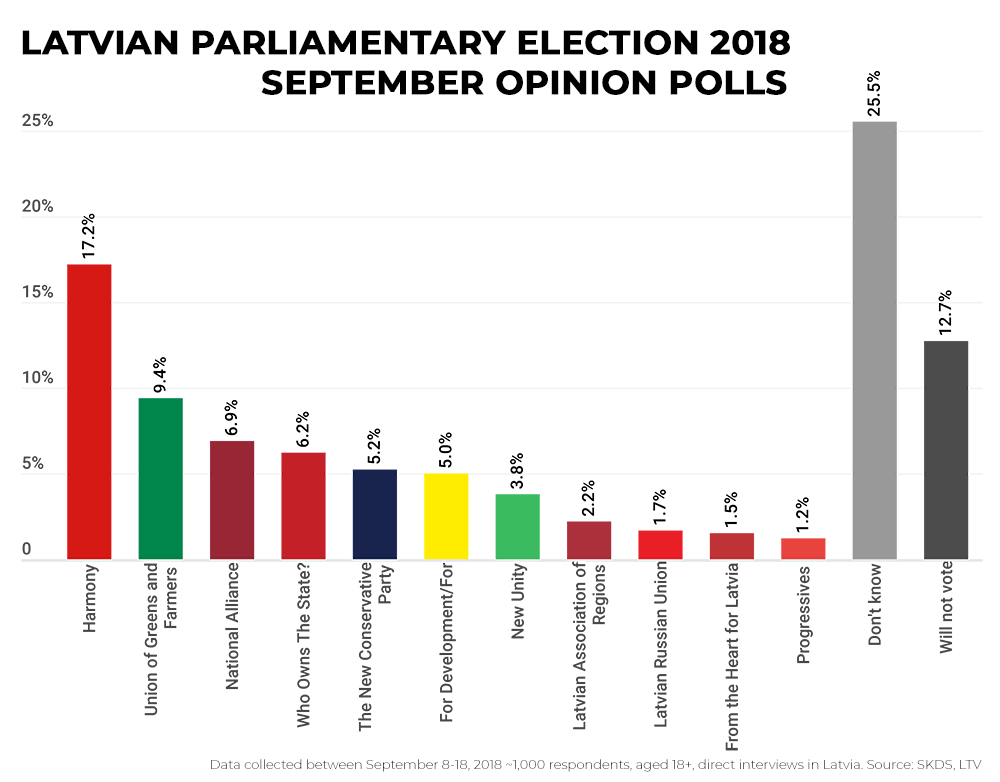

The most recent opinion polls at the time of publishing this article.

Harmony got the most seats (24 out of 100) in the last parliamentary elections, but it was left out of the government – mainly because it is seen as “Russian”. It did not vote to condemn Russia’s annexation of Crimea; it promotes lifting EU/US sanctions against Russia; and few of its MPs voted for the Magnitsky Act – none of which helps its prospects of ever forming a government.

In 2018, Harmony broke its cooperation agreement with Putin’s United Russia. To broaden its appeal, it has tried to rebrand itself as a party of Western social democrats. It has joined the S&D group in the European Parliament and hired Christian Ferry, a top US political consultant (who worked for two US Republican senators, Lindsey Graham and late John McCain) to assist with strategy and messaging.

The party’s leader, Nils Ušakovs, has spent some 8 million euros from public funds on self-promotion in social media in recent years. After Re:Baltica disclosed this, Ušakovs filed a criminal defamation claim against us.

However, Harmony has its best chance ever to get into the government, thanks to the rise of Trump-style populists who seem willing to cross a long-existing red line in Latvian politics.

KPV LV (Who owns the state?) was founded in 2016 by former actor and MP Artuss Kaimiņš. Elected in the current parliament from another small party, Kaimiņš, who cut a colorful figure by filming parliament committees and plenary sessions with a small video camera and broadcasting them live, has been attacking media figures as corrupt, dishonest and out-of-touch. Its PM candidate, attorney Aldis Gobzems, has publicly threatened to “personally fire” a journalist from the public broadcaster “when I am prime minister” over what he sees as wasting taxpayer money by being “mockingly superior”. The main message of the party is disruption of the current political elite, slimlining government in seven ministries and introducing one official information channel to inform the public about government decisions made behind closed doors. The party hopes its approval rating is higher than current polls show, as it enjoys popularity among expat Latvians in the UK and Ireland who are not included in the local opinion polls.

Like Ušakovs, KPV LV leaders try to fight media exposure of their exaggerated promises and outright lies not by trying to sue in civil courts but by getting criminal cases opened. KPV LV asked the police to open a criminal investigation of Re:Baltica for defamation after we published a story on Harmony’s and KPV LV‘s possible connections to a former Latvian oligarch, Ainars Šlesers, who today is making money doing transit business with Russia.

A local business paper (formally owned by a friend of Šleser’s) has run several articles smearing its opponents as sorosites (alleged agents of billionaire philanthropist George Soros, the target of popular rhetoric against liberals in many Eastern European countries). In protest, a lone journalist resigned, saying that she found unacceptable what the owners were doing to the once reputable paper.

Just last week the post-boxes of the Latvian electorate were stuffed with a free special edition of the paper, which combined all the dodgy coverage in one.

Dienas Bizness covers attacking political rivals of Harmony and KPV LV, using rhetoric alluding to “Soros” conspiracy theories. Source: Dienas Bizness

The dominant feature of these elections is fragmentation (16 lists competing) and the end of the force which has dominated Latvian politics for the last 16 years. Center-right Vienotība (Unity) has ruined itself by internal intrigues and is trailing with 5 percent in the polls. Former supporters of Unity have formed several new parties (liberal For Development/For! and the New Conservative Party, led by a former justice minister from the National Alliance and former high-ranking anti-corruption agency officials) which are all fighting each other to get over the barrier.

The divide between these parties has been mentioned as one of the reasons why a week before elections 25.5 percent of voters claim they still have not decided for whom to vote. Although “I don’t know/haven’t decided” has been jokingly called the biggest party in Latvian politics for years, the level of uncertainty before these elections is unprecedented.

The article by Inga Springe was originally published by Re:Baltica