In the year before his arrest for spying for Russia, Mateusz Piskorski exchanged more than 100 emails with Russian politician Sargis Mirzakhanian. We have proof that people working at the Kremlin planned Piskorski’s moves.

- Mirzakhanian created and coordinated a network of Russian agents in Europe, and Piskorski was one of his most important partners.

- His trial has dragged on for five years. The prosecutor’s office refused to disclose whether it has evidence of Russian control of Piskorski’s actions.

- Meanwhile, an acquaintance of Piskorski from a pro-Russian rally has surfaced in an important position at the Polish Agricultural Social Insurance Fund (KRUS).

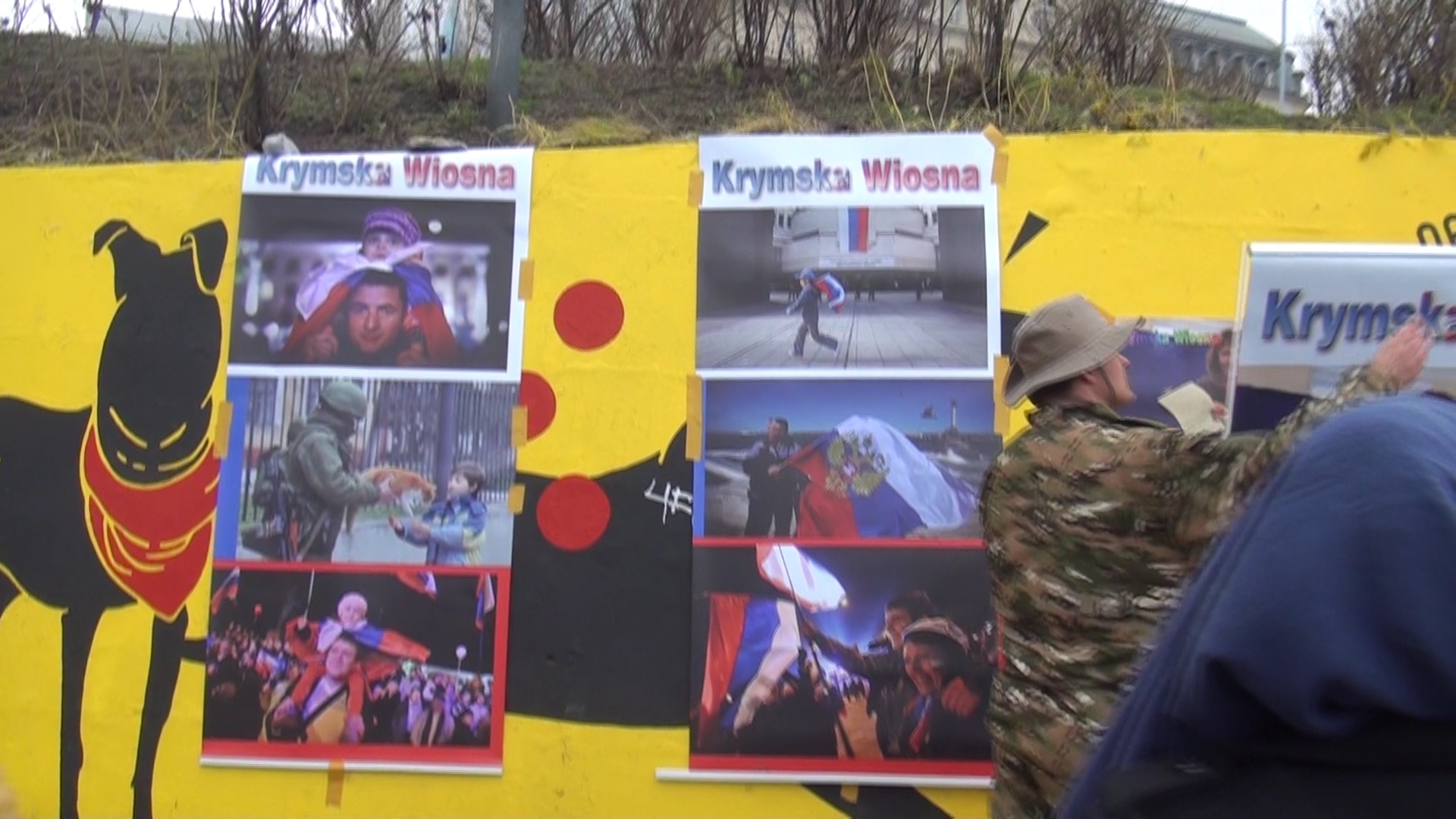

In front of the entrance to the Centrum metro station in Warsaw, there is a busy square. On one wall, there are propaganda photos of smiling families with Russian flags. There are photos of people casting ballots into ballot boxes and soldiers in Russian uniforms among children. On each photograph is the slogan: “Crimean Spring.”

It is a March afternoon in 2016. Two years have passed since the illegal referendum in Crimea, in which the peninsula’s residents were expected to agree to join Russia.

In front of the subway station, a dozen or so people of Mateusz Piskorski, the then-leader of the pro-Russian Change party, now accused of spying for Russia. The atmosphere is picnic-like.The activists treat passersby to tea. But what on the surface looks like a spontaneous happening by a group celebrating the occupation of Crimea is a planned action. Its script was written in Russia.

The authors are associates of Sargis Mirzakhanian, a former Russian Duma staffer and assistant to former Just Russia party deputy Igor Zotov. At the time, Sargis Mirzakhanian was also the leader of an informal organization, the International Agency for Current Policy.

As an international investigation by journalistic organization OCCRP revealed, there are many indications that Mirzakhanian’s agency had ties to the Kremlin: the politician exchanged more than 1,000 emails between 2014 and 2017 with Inal Ardzinba, who worked for Vladislav Surkov, then a key advisor to Vladimir Putin.

Mirzakhanian’s email inbox, the contents of which were accessed by Ukrainian hackers, also contained 117 email exchanges with Mateusz Piskorski. Thanks to them, we know how people in the Kremlin cooperated with the politician accused of espionage and the groups he led in Poland and Europe.

From Crimea to KRUS

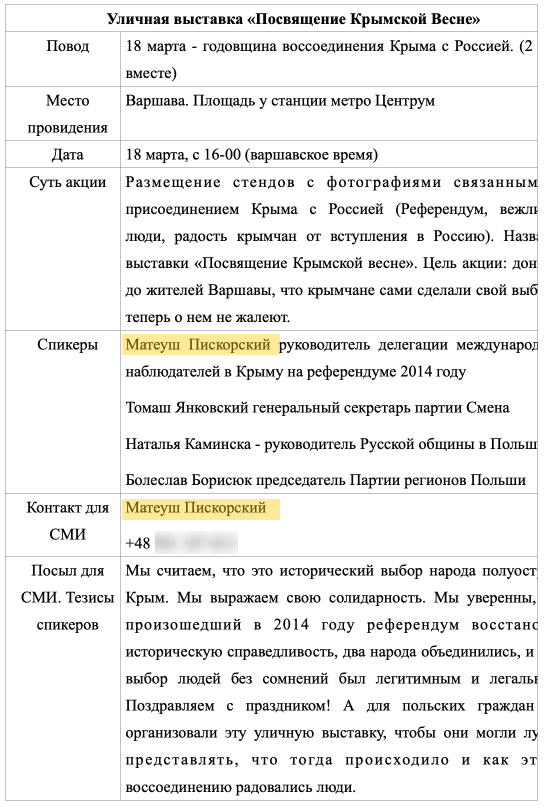

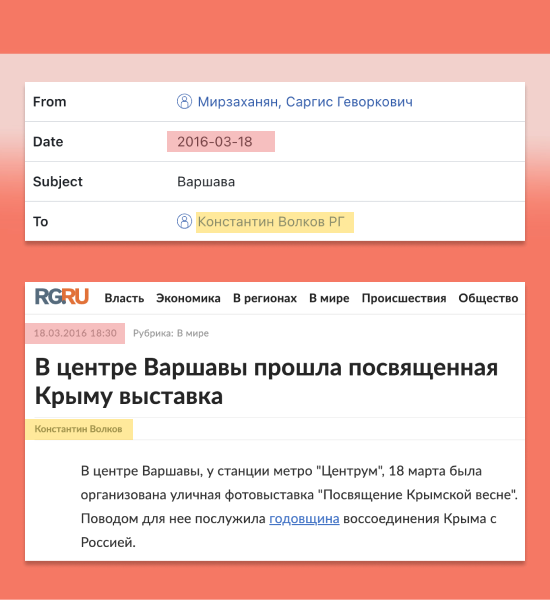

On March 17, 2016, a day before the Change picket in front of the metro station, a script for the Warsaw demonstration fell into Sargis Mirzakhanian’s email inbox. It was sent by Stepan Mancurov, a good friend of Sargis: media expert, lecturer at the Russian Economic University, and co-organizer of the Agency’s projects.

“The purpose of the action: Placement of stands with photos related to the annexation of Crimea to Russia (referendum, grateful people, joy of the Crimean people at the annexation to Russia). The title of the exhibition is ‘Dedication to the Crimean Spring.’ The purpose of the action: to convey to the people of Warsaw that the people of Crimea made their own choice and do not regret it.”

In addition to Piskorski (who is presented as “head of the delegation of international observers to Crimea for the 2014 referendum”), the plan called for speakers to include Party of Change secretary Tomasz Jankowski (we described on Frontstory.pl how he met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in Moscow in December 2022) and Boleslaw Borysiuk, leader of the Party of Regions, which was formed on the ruins of Samoobrona (Self-Defence), a populist party.

Borysiuk heads the farmers’ trade union “Regions” to this day. Interestingly, he has also overseen the state-run Agricultural Social Insurance Fund (KRUS) since February 15, 2023. He came to the Agricultural Social Insurance Fund Council on behalf of his union. The Council works closely with the Ministry of Agriculture, and Borysiuk gets almost PLN 3,000 a month for this.

What did KRUS have to say about the presence on the Council of a man who engaged in pro-Russian pickets in 2016? Teresa O’Neill, a spokeswoman for KRUS, explains that this was a decision by the Minister of Agriculture. This was confirmed by Malgorzata Ksiazik, a spokeswoman for the ministry, who added, “The ministry (…) has taken steps to clarify the information presented by this reporter.”

Let’s go back to 2016, under the Centrum metro station. Mirzakhanian’s script includes a phone number for Mateusz Piskorski and a brief description of the main message of the demonstration. That same day, Mirzakhanian sent it out to several Russian pro-government journalists.

A day later, on March 18, a report featuring photos of the picket in front of the Metro (the photos were taken by his associates) was sent by the Change leader to Sargis Mirzakhanian and his friend Stepan Mancurov. The photos show both Tomasz Jankowski and Boleslaw Borysiuk. Also in the crowd is Nabil Malazi, a pro-Russian anti-vaccinationist and deputy head of Change at the time.

Tomasz Jankowski. Source: leaked emails

When we asked Tomasz Jankowski if he was given guidelines on the picket and the content of the speeches, he denied it. “I myself never wrote speeches, I never read them from a sheet of paper, and we planned and approved demonstrations at party board meetings. The name Mirzakhanian doesn’t say anything to me either.”

Source: leaked emails

Boleslaw Borysiuk got upset when we ask about Piskorski. He threw out a curse word and interrupted when we try to ask a question. “I have had no contact with him since 2012, you understand!”, he fretted and ended the conversation.

Soon, Sargis Mirzakhanian started sending out an account of the picket in Warsaw to Russian journalists. There are quotes from Borysiuk and Jankowski’s speeches and a brief description: “The event was attended by well-known Polish political and public figures…. The participants treated Varsovians to Crimean tea and talked about the history of the Crimean Spring, expressing solidarity with the Crimean people.”

Polish journalists ignored the picket. But the coverage made its way to the Russian propaganda media.

On March 18, 2016, more than a dozen items about Polish politicians’ support for the annexation of Crimea appeared in Russian outlets (most are based on Mirzakhanian’s memo). Photos sent to him by Piskorski end up in several reports.

Just a nice guy

In Sargis Mirzakhanian’s email archive, Piskorski’s name first appears in April 2015.

“Mateusz Piskorski – Chairmanman of the European Center for Geopolitical Analysis, Polish citizen, political analyst, former member of the Polish Parliament from the Self-Defense party and member of the Parliamentary Committee on International Affairs. Leader of the ‘Change’ party. Member of the International Anti-Fascist Committee. Recently issued a statement on the issue of restitution in Western Ukraine….He’s just a nice guy,” Oksana Shkoda, a Ukrainian-born pro-Russian journalist and Putin supporter who was convicted in the 1990s for ties to a drug trafficking group, wrote to Mirzakhanian.

In 2011 Oksana Shkoda went on election observation missions on behalf of the same organization (CIS-EMO) with which Piskorski would go on to observe the referendum in Crimea. She took photos with separatist commanders in Donbass. In 2014, she moved to Moscow. There, she appeared at press conferences and called on Putin to start a war with Ukraine.

We contacted Oksana Shkoda on Telegram. We asked about her acquaintance with Piskorsky and cooperation with Mirzakhanian. The journalist stiffened: “Excuse me, am I obliged to answer questions given that Mirzakhanian’s correspondence was accessed illegally? That is, the email box was hacked and I have to explain its contents?”

We inquired about the details of the cooperation with Piskorski, but Shkoda would not write us back. We checked: she still follows Piskorski’s posts on Telegram, and quotes him in her propaganda texts.

Oksana Shkoda and Igor Strelkov-Girkin, Russian officer, GRU Spetsnaz reserve colonel. In 2014, he was the commander-in-chief of pro-Russian separatist militias in Donetsk. Accused of shooting down in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Malaysia Airlines Boeing. Source: https://v-n-zb.livejournal.com/

In an April 2015 email to Mirzakhanian, Shkoda wrote that she looked forward to working with Piskorski. She would like Béla Kovács, a former Hungarian MEP, to join the group Mirzakhanian is putting together as a package with the Pole, she said. Kovács, nicknamed “KGBéla” in his home country, would go on to be convicted of spying for Russia in 2022. Shkoda wrote that, admittedly, he has a contact for Kovács, but “through Piskorski (they communicate) it would be easier.”

Less than two months later, the first traces of correspondence with Piskorski appeared in Mirzakhanian’s email inbox. On June 6, the Russian politician sent him an invitation to the “Ukrainian Forum” in Kiev. This is a debate where experts are to discuss the shape of Ukraine’s new constitution.

Piskorski was the intermediary in this issue. He received invitations to the debate addressed to European politicians, including German AfD MP for 2017-2021 Lothar Maier and former Dutch MEP Daniel van der Stoep.

The Young Germans’ dream

It is in this role—that of intermediary and organizer—that Piskorski appeared in correspondence with Mirzakhanian. The emails he received were filled with airline tickets and passport photos of European activists invited by organizations in Mirzakhanian’s orbit. The mechanism was as follows: Piskorski sends the Russian the data and passport photos of politicians and activists, and Mirzakhanian sends back the plane or train tickets.

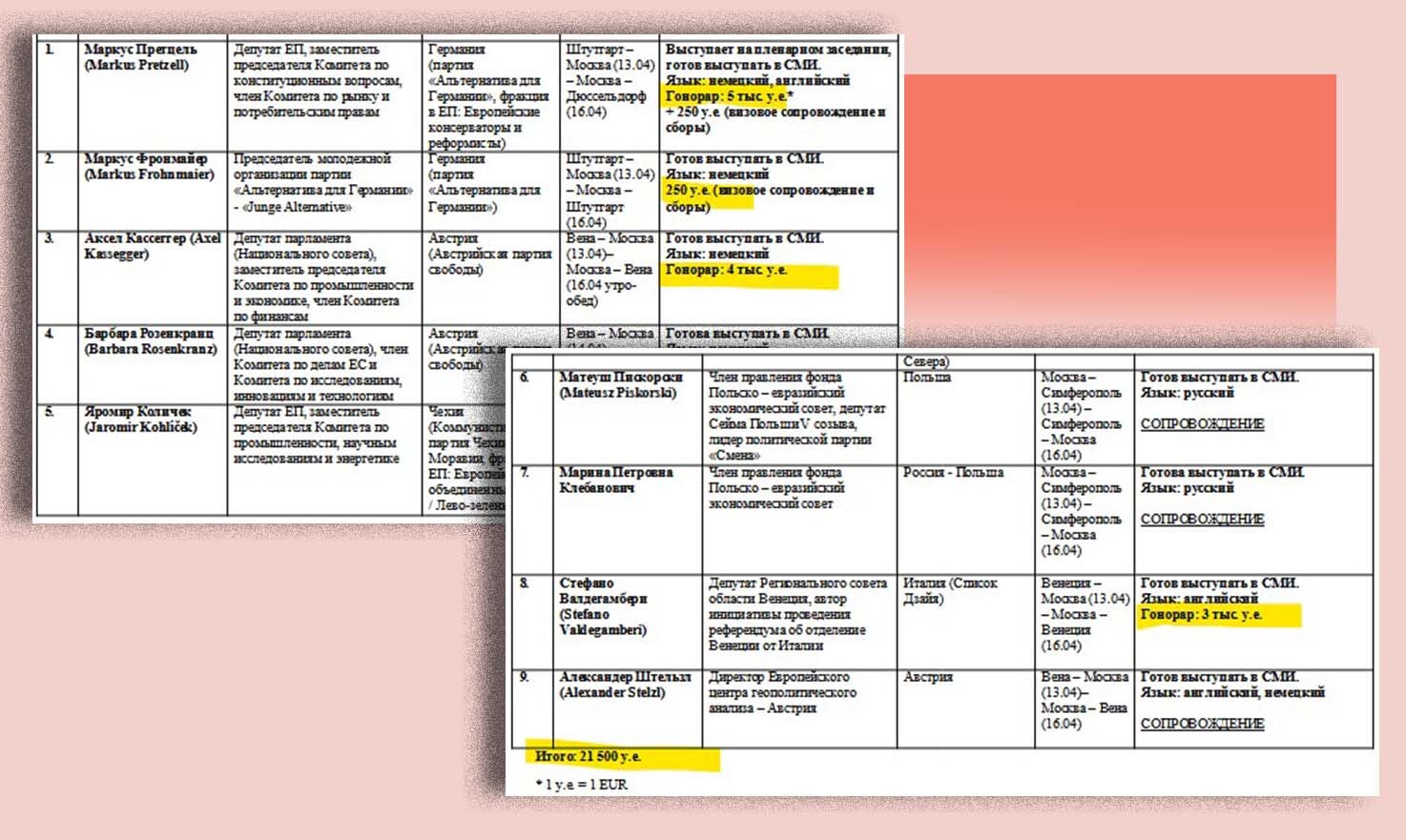

In April 2016, Piskorski acted as an intermediary to bring seven European politicians to Yalta for the annual Economic Forum.

A month before the event, he mentioned one of them to Mirzakhanian: “Text about our candidate in Die Zeit.” He attached a profile of Markus Frohnmaier. The material in the weekly Die Zeit is titled, “Away from the West. The head of the AfD youth group dreams of a new Europe—as a partner to Russia.”

Markus Frohnmaier, a young AfD politician, will lead Baden-Württemberg’s local government to publish opposition to the Union’s sanctions on Russia after the Yalta conference. Emails disclosed by OCCRP show that Mirzakhanian was preparing plans to finance Frohnmaier’s election campaign, and the agency he headed was working on a draft anti-sanctions resolution submitted by the AfD.

Markus Frohnmaier did not respond to our request for comment.

In early April 2016, Piskorski sent Mirzakhanian a photo of the AfD German’s passport. Then a finalized list with the names and short biographies of seven European politicians. He also included himself and his wife, Marina Klebanovich.

A document drafted before the Yalta forum in 2016, indicating honoraria totaling 21,500 euros for European politicians. Source: leaked emails

According to Mirzakhanian’s emails, participants in the Yalta conference were to be paid salaries totaling 100 thousand zlotys. Travel expenses, totaling nearly 590 thousand rubles—or 30 thousand zlotys at the average exchange rate of April 2016—were covered by the organizer.

A very positive observer

In the summer of 2015, when Mateusz Piskorski came into contact with Mirzakhanian, he was already an experienced politician—a recognizable former MP and spokesman for Samoobrona. He moved freely in the parliamentary backstage and had contacts among politicians. He was considered an expert, a man with knowledge of Russia, often speaking on issues of Russian-Ukrainian relations—usually in line with the official Kremlin line.

Election observation missions were Piskorsky’s key and most lucrative activity. The think-tank he heads, the European Center for Geopolitical Analysis (ECAG), has more than a dozen such trips to its name. Piskorski participates and recruits a number of politicians to participate in the missions, with party leaders such as Leszek Miller and Andrzej Lepper going on election observations.

On September 13, 2015, regional elections were held in Russia. A month earlier, Piskorski presented Mirzakhanian with a plan and cost estimate for the observation mission. The cost is $40,000, including airline tickets, on-site transportation, and accommodation. How does Piskorski’s election observation mission differ from others conducted by established centers, such as the OSCE? By methodology: “The basic principle is that the tradition of political procedures and institutions in a given country is decisive (there is no common template for one ‘democracy’),” Piskorski writes.

When ECAG observed the 2014 referendum in Crimea, it found no irregularities.

Piskorski was very busy. He sent another project to Mirzakhanian, this time a mission to Chechnya. This is new to his portfolio. In addition to election observation, ECAG now wants to monitor human rights in Chechnya. “The delegation consists of politicians from different political parties who have a positive or neutral attitude to Russian foreign policy,” Piskorski advertises.

Piskorski estimated the budget for such a mission at 62,500 euros, with between 4,000 and 7,000 euros going to each participant “depending on status.” In exchange for coordination, Piskorski’s ECAG is to receive 6 thousand euros. The plan to send a mission to Chechnya and local elections in Russia wouldnever get beyond the idea stage.

An active and notorious wife

Correspondence with the Russian abruptly stopped. In May 2016, Piskorski sent Mirzakhanian one last email—and was detained by the Polish Internal Security Agency (ABW) the next day.

According to the emails revealed by OCCRP, his role in organizing the politician’s network was quickly taken over by his wife, Marina Klebanovich. Klebanovich is more active than Piskorski in establishing a relationship with Mirzakhanian. She coordinated contacts with Italian politicians and arranged payments for pro-Russian publications in Germany and Austria.

Klebanovich herself cut her teeth in the CIS-EMO (Commonwealth of the Independent States Election Monitoring Organization), established in 2004 by her former husband, Alexei Kochetkov. CIS-EMO organized election observation missions almost exclusively in places where Moscow has interests, as well as in separatist territories occupied by the Russian army (in South Ossetia, Abkhazia or Transnistria). The observation reports presented by CIS-EMO always turned out to be in line with the Kremlin’s political goals.

Ukrainian political scientist and expert on Russian influence Anton Shekhovtsov, among others, has written about Marina Kochetkova (maiden name Klebovich) and her activities in CIS-EMO. Kochetkova observed, among other things, illegal referendums in Transnistria in 2006 and a year later in Abkhazia.

A month after Piskorsky’s arrest, Klebanovich returned to Moscow. She told Russian television about her husband’s arrest: ” Mateusz is in pre-trial detention. A lawyer let me read a note from him, in which he says, ‘please consider me a political prisoner, don’t give up, everything will be fine.'”

During this time, messages from Klebanovich began to appear in Mirzakhanian’s email inbox. In total, they would go on to exchange more than 190 emails.

In one of them, dated August 2016, Klebanovich asks the Russian if he will agree to become a witness in the Piskorski issue. “Matthew wants to know if I can give your address to his lawyer. The issue is whether you could be a witness in his case, she didn’t give any details, she said she would send you. He is asking for three more people.”

Mirzakhanian replies: “I need to talk to you urgently! Turn on the phone.” In their email correspondence, they do not raise the issue of detention again. Marina Klebanovich had not responded to our questions by the time of publication.

Was Mirzkhanian and Piskorski’s correspondence included in the evidence gathered by the prosecutor’s office in the Piskorski case? Did the prosecutor’s office attempt to call Mirzakhanian as a witness?

The Press Department of the National Prosecutor’s Office wriggled out of an answer. It claims that it is the court in which the Piskorski case is on the docket that should answer these questions. The prosecutor’s office is no longer “the disposer of these proceedings.”

Is it recording? I am not a spy

Mateusz Piskorski, before he meets with us, set his conditions: he wants to record the conversation and also wants to ask questions “in connection with the journalistic material he is preparing on some media.”

We meet in a cafe in the suburban town of Wolomin. Before we start talking, he pulls out a document: an opinion of the UN Human Rights Council on his issue. “Read it. I was a political prisoner,” declares Piskorski. He says that today he makes a living from translations, and the website Myśl Polska, where he publishes, does not pay him a penny. He lives in Szczecin, and only passes through Wolomin.

We ask about his emails and relationship with Mirzakhanian. Piskorski answers, weighing his words: “I don’t believe in the veracity of these emails, but if we assume for a moment that they were obtained by hackers, I don’t consider them a source. They were obtained through a crime. And judging by the contents of my inbox, they were simply fabricated. And I wouldn’t call our contacts cooperative.”

We show him the messages he exchanged with Mirzakhanian. “Allegedly me, I send to alleged Sargis, that’s the version we stick to,” he replies. He denies that he corresponded with the Russian from his private mail: “This is practically impossible. On private or social issues, I may have sent. I do not deny that I sent scans of passports of participants of some conference to its organizers, but not from the mailbox we are talking about.”

He supposedly used an email from the domain of the organization he headed, ECAG, as a business one. That one is long gone, and the archive is gone. “I may have corresponded with Mirzakhanian, because the latter was an assistant to Igor Zotov, with whom I wanted to discuss the lifting of the embargo on certain Polish products. But the only emails I found in a private inbox concern the exchange of photos from the Yalta Economic Forum. That’s where we got to know each other”, Piskorski recalls.

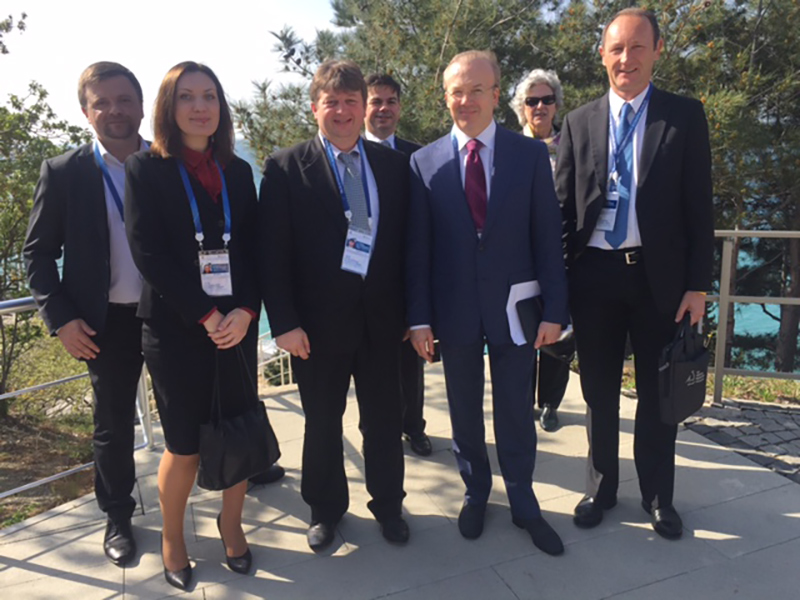

From left to right: Mateusz Piskorski, Marina Klebanovich, Stefano Valdegamberi, Robert Stelzl, Andrey Nazarov, Barbara Rosenkranz, and Axel Kassegger posing together at the 2016 Yalta International Economic Forum. Source: leaked emails

Has the prosecutor’s office secured the inbox from which he emailed Mirzakhanian? “I would very much like to tell you more, but my case is classified, contrary to the requests I made for openness.” This is an incantation Piskorski will use several times. According to him, the material the prosecution has is too weak to convict him. That’s why the case before the court has been dragging on since 2018.

-”Did you spy for the Russians?”

– “No. Never in my life,” he stresses, leaning into the recorder.

A long road to the verdict

Piskorski, who was released in May 2019 after nearly three years in detention, has returned to his role as a political commentator in pro-Russian media. In mid-February, the Myśl Polska website published his interview with nationalist ideologue Aleksandr Dugin, who is often dubbed “Putin’s brain.”

As we revealed in August 2022 on Frontstory.pl, the serious allegations did not prevent Piskorski from gaining access to the Polish parliament. Thanks to his former MP’s card, he has had access to the parliament building since his release from detention. It was only in July 2022, when he tried to enter a meeting of Grzegorz Braun’s team, that the Marshal Guard banned him from entering the building.

Earlier, in March 2022, Piskorski appeared at a meeting of First Lady Agata Kornhauser-Duda with refugees from Ukraine as an interpreter, as reported by Wirtualna Polska. The President’s office explained that it was not responsible for organizing the meeting, and immediately informed security services of Piskorski’s presence. For the meeting with the first lady, Mateusz Piskorski had been recommended as an interpreter by attorney Ewa Bartosiewicz, his ex-wife and a local Law and Justice councilor from Wyszków. When the issue was reported in the media, Bartosiewicz was dismissed from the supervisory board of Mana Solid Invest, a company affiliated with the state-run NASK institute responsible for cyber security. Bartosiewicz also resigned from the Law and Justice party.

Piskorski’s trial is taking place behind closed doors. It is not known what is in the evidence. The Polish National Prosecutor’s Office conveyed what is in the indictment, however, in an official announcement in 2018. According to it, Piskorski “conducted large-scale activities and, using his social, professional and political position and contacts among domestic and foreign politicians and journalists, influenced social groups in Poland and abroad. In Poland and abroad, he promoted the political goals of the Russian Federation.”

Mateusz Piskorski’s lawyer, Professor Piotr Girdwoyń, declined to speak to FRONTSTORY.PL. He sent a text message, saying, “I don’t comment on client issues.” The next hearing in the Warsaw court is scheduled for the end of March.

Mateusz Piskorski still uses the same mailbox from which he emailed Sargis Mirzakhanian. Mirzakhanian himself disappeared from public space and social media after the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

Konrad Szczygieł is an investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL. Previously, he was a reporter at Superwizjer TVN and OKO.Press. Since 2016, he has worked with Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He was shortlisted for a Grand Press award (2016, 2021) and an Andrzej Woyciechowski award (2021). He is based in Warsaw.