Illustration: James O'Brien (OCCRP) 2024-02-09

Illustration: James O'Brien (OCCRP) 2024-02-09

Davy de Valk had a quiet life in Rotterdam. He had a girlfriend, two children and went to the football, where he occasionally got into fights. He lived on social welfare, and spent his nights frequently alone, gaming.

At one of the schools in Rotterdam, he learned the basics of programming. There he learned some of the basics of penetration testing – otherwise known as hacking.

As the market for cocaine in the US shrinks every year, drug lords look for new markets.

The purity of cocaine on European markets has increased significantly, while the wholesale price – around 27,000 euros per kilogram – remains the same.

The drug lords who smuggle cocaine into Europe pay great expense for transporting the drug from Latin American farmers – the so-called ‘cocaleros’ – to the gates of European ports.

The cocaleros themselves and their sales coordinators receive only approximately $1,700 per kg of cocaine hydrochloride. Whilst controls in many Latin American ports from where cocaine travels to Europe remain weak, the largest European ports such as Rotterdam, Antwerp or Hamburg invest millions of euros every year in increasing automation and security measures.

These measures could be a problem for cocaine importers, but according to information obtained by Investigace & OCCRP – it is not an insurmountable problem.

Encrypted chats reveal the role of the hacker

On February 14, 2020, customs officers in Costa Rica were in for a Valentine’s Day surprise. Hiding in a container with flowers bound for the Belgian port of Antwerp, was four tons of cocaine. The Costa Rican police celebrated their success by posing among the kilo packages of confiscated cocaine, and put out press releases.

But the Costa Rican police only arrested the driver who brought the container to the port. They asked who put him up to it. The man did not know, and the case ran cold.

Three months later, across the Atlantic, the Dutch police began to look into the case. After accessing messages from two encrypted communication platforms: EncroChat and SkyECC – bespoke encrypted chat platforms used for organised crime – they discovered someone instrumental in the whole affair. A forty-one year-old man who obtained crucial data from the IT systems of the ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam from the comfort of his home.

Officially unemployed, unofficially Davy de Valk had a lucrative side-hustle. With little training, he made hundreds of thousands as a blackhat hacker for organized crime – in one very peculiar niche. Davy specialized in penetrating the IT systems of major European seaports and then sold the information to facilitate the smuggling of cocaine.

Based on court records, police reports, interviews, encrypted messages and a digital forensic analysis of the case, reporters of Investigace pieced together just how Davy, an outside amateur, together with his collaborators were able to access valuable logistics information from the IT systems of two of the busiest European ports for drug traffickers.

Digitization creates new opportunities for hackers

Previously, if drug lords wanted to smuggle cocaine into Europe, they had to pay a whole string of corrupt port workers – from the crane operator to the customs officers to the porter.

But the automation of maritime logistics has opened up new possibilities. Thanks to information from hackers, drug traffickers can access key port logistics information using only one corrupt employee who inserts a USB stick into one computer, and a truck driver to pick up and deliver the cargo.

All Davy de Valk had to do was get to a female port employee who could take his USB key, follow his instructions, and plug it into a computer for one minute, giving her a reward of 10k. From there he would penetrate the network and view crucial information from the terminal operator.

He wasn’t, it appears, even a very good hacker. According to one independent analysis of his techniques, he used older malware and exploits that come up in basic courses, without even properly clearing logs to cover up his actions, or cleaning up after himself.

“This is pretty low skill work by the hacker. They’re using three and four-year-old (at the time) off-the-shelf exploits and making little attempt to obscure what they’re up to, or clean up afterwards,” cyber security expert Ken Munro of Pen Test Partners later commented, after analyzing the case. “This is a so-called ‘noisy’ attack, which would have triggered a lot of alerts if Antwerp’s port systems had been set up to detect such actions.”

For half a million euros, de Valk offered crucial information for criminals – to help pick which container is safe to load cocaine into in one of the Latin American ports, and instructions to pick up the drug from a container with a foreign shipping company afterwards. He would even offer to create all the necessary corresponding documentation.

‘Chill and Play’™

Davy loved to play games. He set up a free gaming club for kids, known as ‘Chill and Play’ according to an entry dated 10th February 2016 in local journal Krant, aiming to “keep kids off the streets”, and hoped to bring in footballer Georginio Wijnaldum to promote the facility.

When the cocaine-trafficking case came to trial, Davy had an incredible defense – he was only working with cocaine smugglers to develop a new game about drug trafficking. He needed to soak up the atmosphere to make it authentic.

The court found his explanation “completely implausible” and sent de Valk to prison for ten years.

His lawyer did not respond to Investigace’s questions about his client and the current status of the case – and of the status of the video game.

Profile photo of Davy de Valk from his Facebook profile.

The huge number of shipping containers handled in major European ports such as Antwerp or Rotterdam offer ample opportunity for drug traffickers to exploit – it is estimated that of the 98 million containers that have been in European ports cleared in 2021, less than 10% were inspected.

According to an internal Europol report obtained by Investigace, a record 160 tonnes of cocaine were seized in the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp in 2021 alone. But experts say, this represents less than a third of the total amount of the drug that passed through the ports.

One of the obstacles to more thorough checks is that the systems of these seaports were designed to “get container cargo or any cargo from point A to point B in the shortest possible time and at the lowest possible cost,” Jan Janse, head of Rotterdam Port, told Investigace.

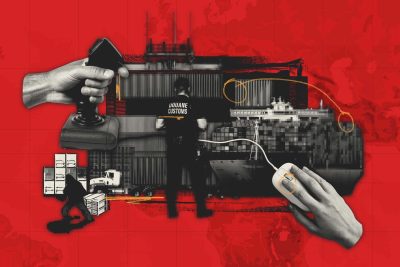

Photos from the Rotterdam Port Police / Rotterdam Zeehaven Politie

Davy’s “lines”

Decrypted conversations from the days and weeks leading up to the collapse of de Valk’s cocaine operation outline what information and at what cost he provided it.

Based on the long-term monitoring of containers, which ones are checked regularly by port customs officials and which ones are not, he was able to recommend to clients where to store their cocaine load so that it would not be noticed by the rightful owner of the container.

He then sent encrypted messages regarding selected containers: “You can put it in this one, it’s not full… and it won’t be scanned”

But clients had to pay a premium for it:

“25k once we get down to it, 225k once I send a tp order (a forged document, a so-called transport order, allowing criminals to pick up a container with a shipment of drugs and take it out of the port) and 250k then,” he explained in a message to the client.

The moment the container arrived in Rotterdam, Davy de Valk ensured a suitable situation for the customer to pick up his cocaine without any problems.

First, in order to prevent a situation where the container and the load of drugs will be taken away by its rightful owner, he wrote an email to the real owners of the container and canceled their order (for the logistics companies that were supposed to pick up and deliver the container to them).

Secondly, based on the data he stole from port’s IT system, he forged documents that allowed the holders to pick up the container. A mafia driver could thus appear on the scene and take the incriminated container to a safe place, where it would be transferred the cocaine into smaller cars intended for further distribution.

Davy charged 500k for this work; and the offer of reliable transport companies that he labeled “my lines”, for thousands of euros.

A fatal mistake

This time, Davy assigned a container used by a company to smuggle cocaine seized in Costa Rica: Vinkaplant, which imports tropical plants from South and Central America to Europe. This type of abuse of a legal company is typically done without their knowledge. In the Costa Rican case, Vinkaplant was not accused of any wrongdoing.

“There are flowers in the container. Easy to load. It’s not overcrowded,” Davy wrote to his client, whose identity the court did not reveal.

But this time de Valk’s “connection” failed: during a routine inspection, the Costa Rican police noticed a crucial discrepancy. The weight of the container didn’t match the information given in the papers. When it was opened, the police discovered that in addition to the ornamental plants, there were also 5,048 black packages inside, most of which contained pure cocaine.

Although one of the biggest cocaine operations caught in Costa Rica in 2020 ended in failure for the smugglers, Davy still boasted: “It was one of my connections, which proves that I know my stuff, otherwise those people would not have loaded [it there]” he said in an encrypted message to the client.

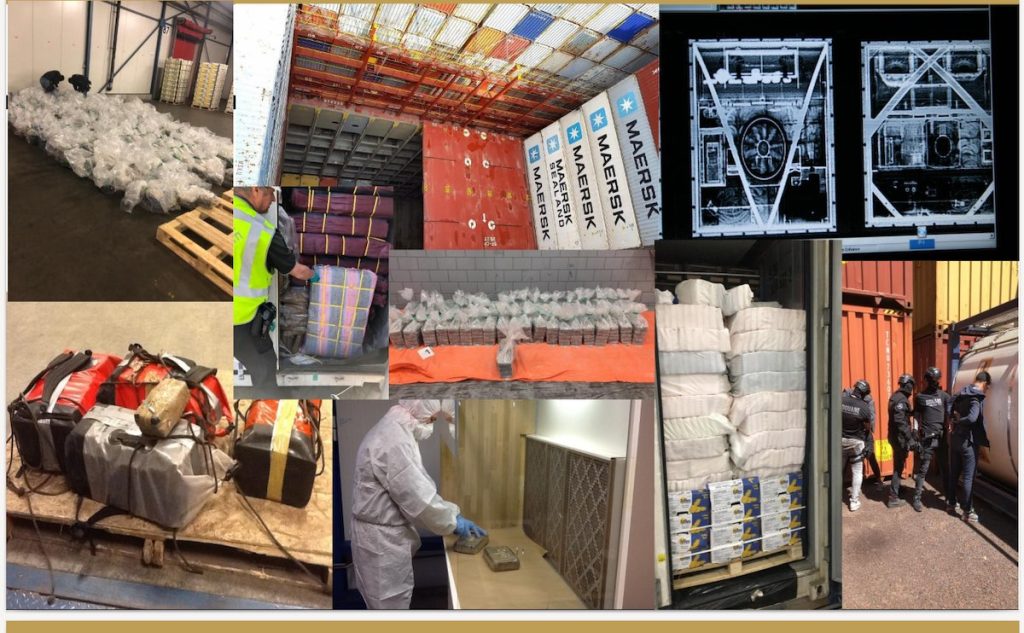

What is container PIN fraud?

Key to de Valk’s successful hacking business was to access the PIN codes of shipping containers that he obtained by breaking into the port’s IT system.

Each container’s PIN code is a unique reference number assigned before the ship arrives at the destination port. In order for the carriers hired by the container owners to pick up the transported commodities at the port, they must enter the correct PIN code.

“In 2018, law enforcement authorities in the Port of Rotterdam increasingly received reports of containers being stolen, disappearing, delivered to the wrong addresses or found in unexpected places,” says an internal Europol report. Police realised that criminal networks had discovered a new modus operandi for drug smuggling: Europol called it “Container PIN fraud”.

Without these codes, smugglers previously had to resort to much more risky methods, such as breaking into containers right at the wharf and then disappearing with their goods undetected.

But dealers discovered that the PIN codes of the containers allow them to pick up the shipment as well as monitoring the status of the container, including when it’s ready for release.

These codes come at a high price: according to an internal Europol report, encrypted chats show that criminals usually pay from 20,000 to 300,000 euros for such codes.

“So far, it’s relatively easy to find someone who has access to the code and pay them money for the information,”Jan Janse, the head of the Rotterdam Police Department police, told Investigace. “If that person doesn’t say yes the first time, organized criminals will continue to pursue them.

“For example, when they are shopping, they will throw a wad of money in his basket, maybe they will try to offer money a third time.”

“But there are, of course, much harsher options – where they show port workers pictures of their children and say, ‘We know where your children go to school’.”

PIN fraud. The hardest part is getting to them. Once you have the PIN, you track the location of the container, take possession of it at the port, drive it to a secure location and collect the contraband from it. Source: Criminal Networks in EU Ports: Risks and challenges for law enforcement, Europol

Meet Bob

After the Costa Rica fiasco, de Valk needed to find a new client, so he offered his services to another Netherlands resident, Bob Zwaneveld.

Prior to his arrest in 2021, 56-year-old Zwaneveld had lived in a caravan for seven years. He was officially unemployed, apart from occasional construction work.

Unofficially, he forged a lively trade with cocaine and weapons, eventually leading to his 12-year prison sentence in 2022.

(Bob Zwaneveld’s attorney did not respond to our questions).

Zwaneveld was receptive to the idea of getting hold of container PIN codes. He knew an intermediary, identified in court only by a SkyECC from 7MIOBC, who provided the pair with a crucial contact: a corrupt clerk from the terminal operator.

After her arrest, she testified. Someone offered her 10,000 US dollars to insert a USB key into her work computer.

Once she agreed, she was given a SKYECC phone – a secure device with an encrypted messaging app – to communicate with 7MIOBC, who shared her questions in a group chat with de Valk and Zwaneveld:

7MIOBC: “… it also asks how long the USB should stay in counting”

De Valk: „1 min“

(…)

7MIOBC: “And then youyou will get With that computer to other computers?’

De Valk: “I have to start here and map that network. Then I need to find the master server and get the admin passwords from it. those passwords are hashed. i have to decrypt them on amazoncloud. it can take a week.”

(…)

7MIOBC: „okay and what else”

De Valk: “they can pick up the USB stick”

De Valk: “Shit. i will do it tomorrow and it will be available for pick up the day after. I have to upgrade my system to windows. then I’ll upload it there and test it.”

De Valk: “As soon as I have the admin password, I will give myself system privileges and delete the logs.”

De Valk: “Until I start doing something real, they won’t see anything.”

Bob: „crazy“

De Valk: “don’t worry, I’ve been doing it for years”

“It’s all under control”

De Valk assured everyone that they were not risking anything, as he would erase all traces of his hack.

“Don’t worry, I’ve been doing this for a long time,” he wrote to the others.

“Just activate the program on the USB, double-click and wait 15 seconds, then you can take it out,” he sent instructions to a port employee on September 18, 2020.

Thus, within a few minutes, they launched the operation.

“Yeah, I got it!” he wrote in a group chat, posting a screenshot proving his access to an employee’s computer, which prominently displayed the word “user” followed by a photo of folders and drives. 7MIOBC he replied with a photo of a USB connected to a computer at the port office in Antwerp.

But not everything went smoothly.

“Hey, I just got past the system intrusion detection, it was pretty shitty. As long as they can stay [port employee]? I need at least two hours,” he tells 7MIOBC, adding “now I need to get SSH going to get through the firewall before I can map the network.”

On September 21, Davy de Valk accessed the Solvo TOS port software. This software, from a company headquartered in St. Petersburg, was procured by Antwerp Euroterminal in 2019 to help manage containers.

“Logs from this cyberattack show de Valk opening the Solvo user manual at 4 a.m., presumably to explore what data he could get through Solvo (such as how to find the location of containers),” writes cyber security consultancy Northwave in its forensic report.

The decrypted messages indicate that de Valk intended to clone port employee identification cards. To the group chat on SkyECC he sent a photo of a computer monitor with the text “badge” and “alfa pass,” a reference to the plastic cards used by port workers to access various work sectors.

Crowds: “We have to get 1 of those 4”

Davy: “all 4 have domain dc rights”

7MIOBC: “And what will we be able to do with it?”

Davy: “we will be in full control”

Davy: “make entry passes, checks at the gate, then I can do everything”

(…)

Davy: “look where is which bin”

Davy: “I already have a lot of that data. staff photos terminal map”

Davy: “where is which camera, I can see footage from them too”

Davy: „pass system – although I can see, but in order to make a duplicate entry card, I would need ww admin”

It is not evidenced that de Valk successfully produced these alfa pass entry cards. But according to Northwave’s report, he repeatedly accessed the Antwerp Euroterminal Solvo system until at least April 2021. Northwave were able to recover information suggesting that de Valk accessed the Solvo container software multiple times between October 19 and April 24, 2021, visiting pages that monitored containers, vehicles, staff passes, and names of transport drivers.

However, it is possible that de Valk continued his hacking activities until the day of arrest. An initial scan of the laptop seized from De Valk shows that on 30 and 31 August 2021, he was still having chat conversations with various people about transport modes and deck cargoes. And he continued to access the Solvo system frequently in this period.

Blackhat turns to blackmail

Davy de Valk was not only a reclusive hacker. One day, he decided to settle a dispute between Bob Zwaneveld and a man known as “Uncle” for a promised reward of 20 kilograms of cocaine. The dispute was over a further 100 kilograms of pure cocaine, which Uncle had apparently deprived Zwaneveld of.

“Then fuck it… I was planning to do it anyway (…) I’m already annoyed by people like uncle, who have been screwing me for several months, bro (…) really we will catch with all that we have, bro,” a distraught Zwaneveld wrote in an encrypted communication to SkyECC user 301226.

In the same conversation, he refers to de Valk as “Hack” – “I just got my uncle on the phone, bro, I told him on his private phone that if he doesn’t have bricks by 10 o’clock tomorrow, we’re done. (…) Hack told him that we were going to his daughter’s place now and that he should go there and we would sort it out.”

However, this did not happen, and on February 14, Davy asked Bob to send him photos of “uncle’s daughter and her personal information such as date of birth”.

“We’ll see how much he likes his daughters,” Zwaneveld replied.

On January 29, 2020, a young woman reported to the police that a man came to her house and told her that her father owed 1.2 million euros. When she told him that she had no idea where the father was and that he should leave, the man was rude and said he would be back the next day with twenty other guys. When the police later showed the young woman a photo of Davy de Valk, she recognized him immediately.

Davy eventually acknowledged it was him, but denied threatening the woman in any way. The court did not accept his explanation and found him guilty of attempted extortion.

“Black Harbor”

When the Belgian police started investigating the intercepted discussions on the SkyECC platform, they hoped to close the so-called “black harbor”.

“The police have given this name to the chains of corrupt port employees, truck drivers and others that enabled the smuggling of more than 200 tonnes of cocaine into Europe,” Kurt Boudry, a Belgian drug investigator, told Investigace. “We had no idea it would be so extensive,” he added.

Rotterdam, Holland, 2022. Photo: Aerovista Luchtfotografie / Shutterstock

According to a 2023 Europol report, PIN fraud in Rotterdam and Antwerp is vastly underreported and also occurs in other European ports.

In some cases, the report says, transport drivers who work with drug traffickers continue on to the official importer and container owner after unloading the contraband, meaning such cases are never detected or reported.

Jan Janse, head of the Rotterdam port police, suggested that the biggest problem in the fight against traffickers lies in their ability to corrupt port staff with money and intimidation.

He added that port authorities and shipping companies are experimenting with ways to tighten security, including by offering staff training on how to resist corruption and limiting the number of people who have access to data that can be misused by traffickers.

“I’m not saying we’re going to win this war. But I am saying we’re capable of fighting it better,” Janse told Investigace.

Text authors: Paul May and Pavla Holcová, with contributions from Interferencia de Radios UCRa and Brecht Castel

The article is part of #NarcoFiles: The New Criminal Order, an international journalistic investigation into global organized crime, as well as its methods and influence. It is also the story of those who are trying to fight back. The project, led by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) in collaboration with the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), was made possible by leaked emails from the Colombian prosecutor’s office, which found their way to investigace.cz and more than 40 media outlets around the world. OCCRP reporters analyzed and verified this material, as well as hundreds of other documents, databases, and witness accounts.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Czech journalist, Pavla Holcová is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism. She is an editor at OCCRP and a member of ICIJ. She was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2023). Pavla is the winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award and, with her colleagues Arpád Soltész and Eva Kubániová, the World Justice Project’s Anthony Lewis Prize Award. She is based in Prague.

Paul May is an ICA-trained anti-money laundering expert and a reporter at the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism, investigace.cz.