In the retrial of Marian Kočner and Alena Zsuzsová the panel of judges of the Specialized Criminal Court did not vote unanimously. Two of the three judges, Rastislav Stieranka and Ružena Sabová, came to the conclusion that Kočner was innocent in the case of the murder of Ján Kuciak, linked to a case regarding the order of murder of prosecutors. But a third member of the panel, Jozef Pikna, was convinced of Kočner’s guilt. Pikna attached his dissenting opinion to the written version of the judgment.

The Ján Kuciak Investigative Center (ICJK) analyzed the arguments of the judges. We compared their conclusions with evidence from the investigation file. The ICJK has access to the investigation file and its attachments thanks to the cooperation with the international organization OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project) on the Kočner’s Library project.

On Wednesday, February 21, 2018, Miroslav Marček entered the house of Aktuality.sk investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and shot him. He also took the life of Kuciak’s fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Marček, his driver Tomáš Szabó and the murder facilitator Zoltán Andruskó are already serving long sentences.

Marian Kočner and Alena Zsuzsová, accused of ordering the murders, were acquitted in the first trial. But the Supreme Court overturned the verdict. The panel, led by Peter Paluda, criticized the Specialized Criminal Court for having assessed some of the evidence contrary to elementary logic. “If it had gone chronologically, evidence by evidence, presented even the unexecuted evidence, it probably would not have reached the acquittal of Marian Kočner and Alena Zsuzsová,” Peter Paluda said in an interview to ICJK about the panel of judges who acquitted Kočner and Zsuzsová in the first trial.

Picture: Visit to the scene of crime, Ján Kuciak’s house. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s library

In the retrial, the murder of Ján Kuciak was linked to another case, one regarding who ordered the murders of prosecutors Maroš Žilinka, Peter Šufliarsky and Daniel Lipšic (which the perpetrators did not complete). The two original members of the panel, chairwoman Ružena Sabová and Rastislav Stieranka, were joined by Judge Jozef Pikna. The three unanimously found Zsuszová guilty, but only Pikna voted in favour of Kočner’s conviction.

Dissenting opinion

In a dissenting opinion, Pikna writes that “the evidence adduced at the main hearing forms a logical and undistorted system of complementary evidence which, taken as a whole, excludes the possibility of any other conclusion than that the defendant Marian Kočner committed the offense…”. According to him, the evidence “proves beyond reasonable doubt that the order for the murder did not begin with Alena Zsuzsova, but with Marian Kočner.”

Judge Sabová and Judge Stieranka justified the decision to acquit Kočner on the basis of the principle of “in dubio pro reo”—”when in doubt, rule for the accused,” and identified Alena Zsuzsová as the sole mastermind of the murders.

Their colleague Pikna, however, did not consider these doubts reasonable. On the contrary, he believes it was clear that Kočner had a motive to have Ján Kuciak murdered. According to Pikna, Kuciak’s articles about Kočner’s frauds were so qualified and supported by analytical work that they created real problems for Kočner, which “in the context of Marian Kočner’s then current efforts to enter politics, was an existential threat to him.”

Judge Pikna does not doubt Kočner’s motivation to have prosecutors Maroš Žilinka and Peter Šufliarský murdered either. Žilinka supervised his criminal cases and Kočner saw Šufliarský as an obstacle to his release from custody (he was in custody before charges were brought against him in the Kuciak case for an unrelated economic crime).

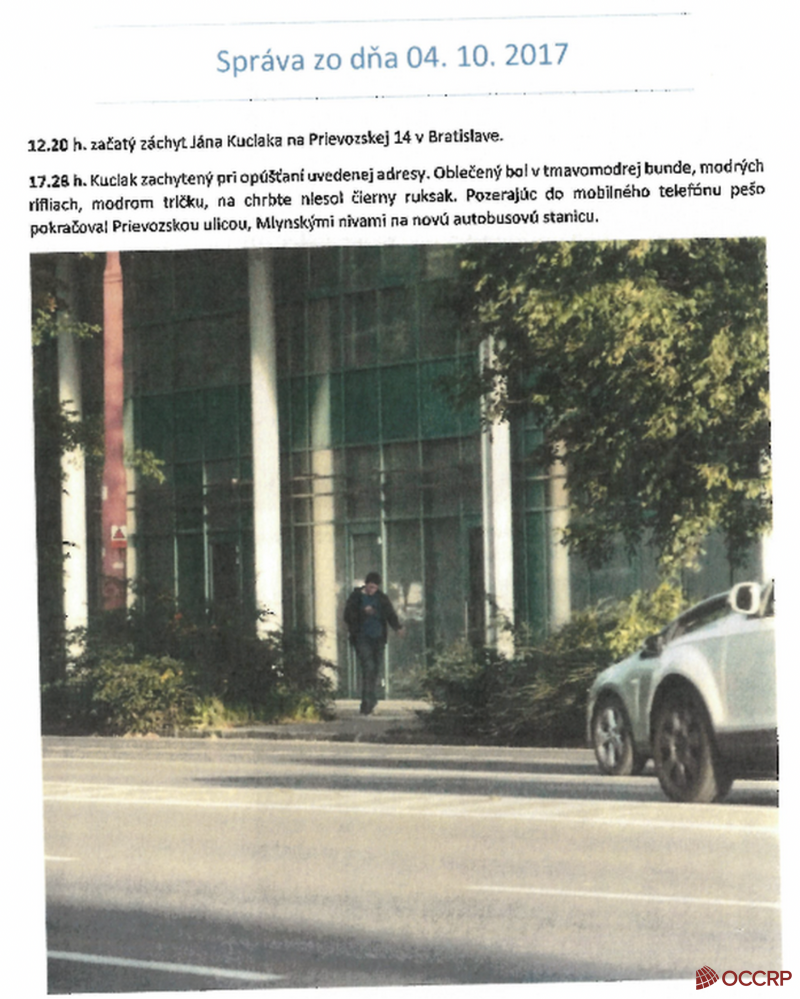

Pikna also considers the fact that he did not threaten Ján Kuciak directly with death, but with discrediting him, to be proof of Kočner’s guilt. Kočner famously called Ján Kuciak on telephone and threatened to dig up dirt on the journalist and his family. Kočner then paid a squad of ex secret service members to conduct surveillance of Ján Kuciak.

Records from the surveillance of Ján Kuciak by this commando show “that Marian Kočner failed to detect and record Ján Kuciak’s negative behaviour… with which he could blackmail or ridicule him through his portal ‘Na pranieri’ and thus eliminate him,” Pikna writes.

According to Judge Pikna, the results of the surveillance, in conjunction in particular with the testimony of Zoltán Andruskó, immediately prove the guilt of Marian Kočner. Andruskó has consistently testified since his arrest that the murders were ordered by Kočner through Zsuzsová.

According to Judge Pikna, “it is impossible that Alena Zsuzsová merely ‘pretended’ to Zoltán Andruskó that she was ordering the murders for Marian Kočner without his actual knowledge.” This was ruled out by other evidence, the judge stated.

At the same time, it was proven that when ordering the murder, Zsuzsová showed Andruskó the photos and the schedule of Jan Kuciak’s day. None of the judges doubted that these were the materials collected by the surveillance commando and that Zsuzsová received them from Kočner. But only Pikna does not doubt that Kočner gave them to her precisely to show them to the murderers.

“That she should have had these materials for the purpose of the portal ‘Na pranieri’ has no logic, because it was only launched in the summer of 2018. There was no reason for her to have them six months in advance,” Pikna argued.

Picture: According to Judge Pikna, Zsuzsová received Ján Kuciak surveillance reports from Kočner in order to use them to order the murder. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s library

In his dissenting opinion, Judge Pikna also countered the claim that Zsuzsova might have had enough money to pay for the murder herself. (Zsuzsova did not only promise to pay, but actually made the payments in cash, meaning that she had access to a not insubstantial amount of money.)Pikna thought the possibility considered by his colleagues in the verdict, that Zsuzsová could have earned money by borrowing money at high interest, to be unrealistic. He asked why, if that were the case, would Kočner continue to finance her daughter?

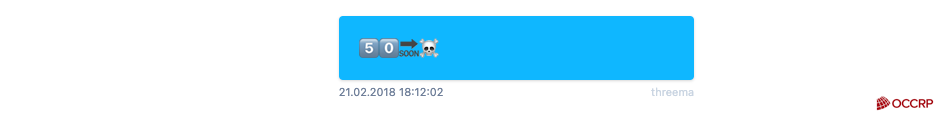

According to Pikna, there was no doubt that Kočner and Zsuzsová communicated in the Threema app and in code. “It is neither possible to interpret it absolutely literally in its entirety, nor to rely uncritically only on the interpretation offered to the court by the individual procedural parties or the experts brought in. At the same time, however, in my opinion, it is not possible to resign oneself from searching for its true meaning,” Pikna writes.

Such hidden meaning is found, for example, in the messages about teeth. Pikna points out that in the Threema between Kocner and Zsuzsova, “it is clear that some things in the communication are merely implied and relied upon to be understood by the other.”

The judge also points out that on the day of the murders of Jan Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová, Zsuzsová explained to Kočner that when one dreams about teeth falling out, then it means, according to the dream dictionary, that someone will die.

Then, the next morning, when she had supposedly learned from Zoltán Andruskó that the murder had been committed, she informed Kočner that “1 has indeed fallen out.” Judge Pikna considered it proof that Zsuzsová had no real problem with her teeth. Thus, in his view a “tooth falling out” must have been code for something else.

Why did they acquit Marian Kočner?

The judges disagreed on the question of whether Marian Kočner was guilty. Judges Stieranka and Sabová voted for his acquittal, and their two votes prevailed. However, they did not dispute that Marian Kočner had a negative attitude towards Ján Kuciak and wanted to take revenge on him. However, in their judgment, they say that he only wanted to take revenge via denunciation, not by murder.

“Apparently driven by a vindictive motive, he decided to resolve this situation by denouncing the journalist and his family,” the judges wrote in their ruling, adding, “for which, however, he had no basis.” But that does not mean he had the intent to kill anyone, they said.

On the one hand, the judges use the argument of “beyond a reasonable doubt.” “The court could not reliably conclude, beyond sensible and reasonable doubt, that the act connected with the killing of Ján Kuciak was committed by the defendant Marian Kočner,” Stieranka and Sabová write. But elsewhere, it seems that the issue is not doubt, but their own conviction of his innocence. They argue, “the court… came to the conviction that Kočner did not have knowledge of the murder of Kuciak before its public disclosure…”

In another part of the judgment, they explain why they did not find Kočner guilty of ordering the murders of the prosecutors: “If Kočner was also involved in the preparation of JUDr. Žilinka’s murder, then he would have made a specific statement about Žilinka in front of Zsuzsová. The court does not detect direct [evidence] and does not have a complete chain of indirect evidence, on the basis of which it could decide without a doubt that Kočner approached and asked Zsuzsová to arrange the execution of the murder…,” Judges Stieranka and Sabová wrote.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence against Kočner were the photographs taken during the surveillance of Ján Kuciak. It has been proven, and has now been acknowledged by the court, that the surveillance of Ján Kuciak was ordered and paid for by Kočner, and that it was he who handed over the materials to Zsuzsová, who in turn showed them to Andruskó when ordering the murder.

According to the verdict, the judges have no doubt about this, but they claim that he did not give them to Zsuzsová to order Kuciak’s murder, but for her to be able to take care of the ‘Na pranieri’ portal. They argue that Kočner did not form his commando to murder anyone murder, but to gather materials for public shaming and denunciation.

“The surveillance of journalist Ján Kuciak… was not aimed by Kočner at obtaining information about Ján Kuciak’s usual way of life, about the usual times of his activities and the places where he stayed, which are necessary to create the conditions for murder…,” Judges Stieranka and Sabová wrote.

But the fact is that the materials from the surveillance of Kuciak contain only information about his usual way of life, activities, daily routine, and places where he stayed. The judgment does not answer the question of why Kočner would have given such photographs to Zsuzsova for public shaming, as there was no material suitable for shaming in them. Even members of the surveillance commando themselves reported that “Kuciak lives like a monk.”

Picture: Ján Kuciak’s surveillance reports capture his daily movements and information such as his address, car registration number, etc. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s library

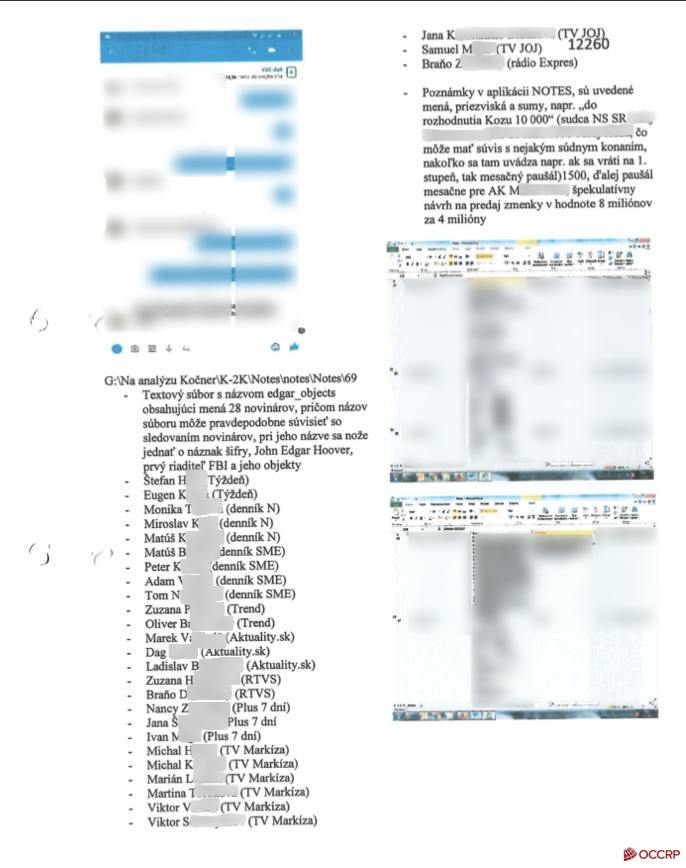

Some of the arguments in the judgment are even contradicted by the evidence in the case file. “In the spring months of 2017, they [Marian Kočner and his accomplice in surveillance, Peter Tóth] drew up a list of journalists, which included 28 names, among which was Ján Kuciak,” the judges wrote in their judgment.

This is not true. Kočner first gave Peter Tóth a list of 28 names in the spring of 2017, but Ján Kuciak was not among them. ICJK previously proved that Kočner decided to have Ján Kuciak surveilled by his commando much later, only after he had the infamous phone call with him in which he threatened the young journalist.

The evidence about this is inside the case file, including the original list of 28 names of other journalists, whom Kočner wanted to publicly shame. Evidence in the case file also shows that Kuciak was illegally searched in police databases (so-called “lustration”) on September 7, 2017, two days after Kočner’s threatening phone call to Ján Kuciak.

Picture: The page of the case file showing that Marian Kočner wrote down the names of those journalists he had already surveilled in the spring of 2017. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s library

Judges Stieranka and Sabová also came up with their own interpretation of Kočner’s communication with Zsuzsová in Threema. According to them, only Zsuzsová communicated in codes, while Kočner not only did not use code, but did not understand them.

The judges argued, for example, that when Alena Zsuzsová wrote to Marian Kočner about the meaning of dreams about teeth falling out, he responded with the message “Relax, dreams are about fuc*ing,” or with a picture of an old woman with no teeth. According to the reasoning of the judgment, this proves that Kočner did not take Zsuzsova’s messages seriously and it is “evidence that Kočner did not even know about the preparation of the murder of Ján Kuciak with a probability bordering on certainty.”

In the very next sentence of the judgment however, they argue that a message composed of the emoticons “50-arrow SOON-Death” cannot be about a reward for the killers (who received 50-thousand euros for the murder) because Kočner would have communicated more carefully on the day the murder happened.

Picture: Threema communication between Marian Kočner and Alena Zsuzsová. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s Library

Thus, on the one hand, the judges did not believe that Kočner knew about the preparation of the murder because he communicated too carefully and did not indicate that he knew what the ciphers were about, and on the other hand, did not believe that he knew about the preparation of the murder because he communicated too carelessly.

Elsewhere in their analysis, they claimed that Kočner did know other ciphers and codes and used them. For example, the code “Puppy” was intended to refer to prosecutor René Vanek in his communication with Zsuzsová.

Why was Zsuzsová found guilty?

All three members of the panel agreed that Alena Zszsová was guilty. According to the judges, she ordered the murder of Jan Kuciak and prosecutors Maroš Žilinka and Peter Šufliarský. She did so “in fear of losing the regular monthly income and other material benefits provided to her by the accused Marian Kočner.”

This motive is not inconsistent with the opinion of the prosecution and Judge Pikna, which states that she did so at the request of Marian Kočner himself. Judges Stieranka and Sabová, however, concluded that Zsuzsová ordered the murder out of her own motive and decision.

In ordering the murder of prosecutor Šufliarský, the judges wrote that the one ordering was “only the defendant Zsuzsová, guided by her naive perception of the power of voodoo practices, which undoubtedly initiated her motive for killing the named prosecutor at the time of Kočner being taken into custody.”

The judges’ reasoning does nothing to explain the fact that, during the trial, it was also shown that Kočner also believed in fortune-telling and other such practices.

In their argument, the judges are sometimes only speculating about Zsuzsová’s motives for the murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová. According to the indictment, Zsuzsová learned of the murder from Andruskó the next morning, immediately informed Kočner by code, and went to see him to arrange the next course of actions or to collect money from him, which she then paid to Andruskó.

In the written reasoning, the judges wrote, in reference to this meeting, that when Zsuzsová “suddenly decided and urgently needed to travel to Bratislava, in the opinion of the court, she was driven to do so only by a strong inner motivation to be in personal contact with Kočner at such a serious moment in her life, which followed the execution of the act she had arranged.” This is not supported by any evidence. In the next sentence, they state that it is not impossible that she also wanted to receive some money from Kočner, “but this reasoning is not supported by the evidence.”

The judges acknowledged that Zsuzsova’s motive for the murders was her financial dependence on Marian Kočner. In several places in the judgment, they wrote that Alena Zsuzsová had no income other than from Kočner. Where did the money come from for the purchase of submachine guns for the killers, for the advance payment for the unfinished murder of prosecutor Žilinka, or for the reward for the completed murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová?

“The only source of her income was Marian Kočner.” The judges confirm Alena Zsuzsová’s financial dependence, but then added their own speculation that she “was probably also supplementing her income by earning interest on the money she received from Kočner.”

Despite the fact that they wrote she “probably” earned some extra cash this way, in the next part of the judgment, they already treat this speculation as a proven fact: “Zsuzsova [was] engaged in the business of making loans at a monthly interest rate of 20%.”

However, apart from Zsuzsova’s claim that she made such a loan to Zoltán Andruskó, there was no evidence of any other loans. Andruskó himself also denied this; according to him, Zsuzsová did not give him a loan, but an advance payment for the murder of prosecutor Žilinka.

“In addition to the income she had from Kočner, she also had other financial income from money trading for a long time, and the sum of these incomes was a sufficient source of funds for the purchase of weapons and for the advance payment for the murder of JUDr Žilinka, or for the killing of Ján Kuciak,” the judges stated, without citing the evidence that led them to that conclusion.

A much simpler explanation was offered by the prosecutors and Judge Pikna: Zsuzsová had the money for the murders because her benefactor, Kočner, gave it to her for it.

The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

Cover photo: Visit to the scene of crime, Ján Kuciak’s house. Source: OCCRP/Kočner’s library

Support independent investigative journalism in Slovakia,

Support independent investigative journalism in Slovakia,

you can donate here.

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.