Illustration: Karl-Erik Leik (Delfi Estonia) 2023-04-27

Illustration: Karl-Erik Leik (Delfi Estonia) 2023-04-27

VSquare has in its possession documents drawn up in Russia three months ago that reveal an influence operation currently being prepared. The operation is centred on the health of the Baltic Sea; its ultimate aim is to incite anti-NATO sentiment in the Baltic states.

In the first days of October last year, a group of Russians and Belarusians gathered in Svetlogorsk, a resort town in Kaliningrad. The group is made up of politicians, academics, and activists, and they are there in a conference centre to discuss how the two countries “truly striving for stability across the planet” can resist the war of sanctions waged against them by the West.

Speakers lament how difficult life is in the western parts of Russia. There is no cross-border trade any more. Building materials cannot be bought in shops. Energy security is under threat.

One of the event’s most authoritative speakers is Alexander Dynkin, President of the Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) of the Primakov Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Dynkin discusses how the balance of power in the Baltic Sea has completely changed, and says it could become NATO’s internal sea. He proposes the creation of a new discussion forum in Kaliningrad under the “conditional name” of Baltic Platform, which, he says, should be similar in size and scope to the St Petersburg Economic Forum.

Aleksandr Nosovich, a well-known local “political scientist and international journalist,” explains in the Kaliningrad Komsomolskaya Pravda a day later that, for the people of Kaliningrad, security and geopolitics are more important than economics, and therefore the Baltic Platform will become “primarily a geopolitical or even military-political forum, and only then an economic, humanitarian, etc.”

A fake journalist and his fake story

Nosovich says that a significant part of research and studies on the Baltic Sea region comes from the Baltic states, and that this is very dangerous for Kaliningraders because “in the absence of an alternative, we are forced to consume information from NATO countries hostile to us.”

Nosovitch is not, in fact, a journalist. He is a Kremlin stooge who has been publicly peddling messages he has been fed by the Russian presidential administration for years. Nor is the Baltic Platform a spontaneous idea born out of a collective brainstorming session, but part of Russia’s ongoing influence operation targeting not only Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, but also the other Baltic Sea states, including Finland, Sweden and Germany.

Vsquare is in possession of a plan submitted to the Kremlin’s Directorate for Cross-Border Cooperation as recently as January of this year. This plan spells out in detail how and for what purpose the Baltic Platform would be created and what its real purpose would be.

VSquare obtained these documents together with colleagues from the daily Delfi Estonia, the Swedish newspaper Expressen, investigative journalism centre Dossier, investigative journalism centres Re:Baltica (Latvia), and Frontstory (Poland), Yahoo News (US) the Lithuanian national broadcaster, German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, broadcasting networks WDR and NRD, and the Kyiv Independent. These documents come from the same series as the documents on the basis of which we published an article on Russia’s “strategic objectives” in the Baltic states yesterday and articles on Russia’s plans to subjugate Belarus and to turn Moldova back on its pro-Russian course in February and March.

“In the new political conditions, the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus face the most complex challenges. The Western world, primarily the Anglo-Saxon part of it, has brought the international order into a state of deep crisis,” says the document, titled, “The Baltics at a time of epochal change: challenges and imperatives for development.”

The document was prepared by IMEMO and the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (or MGIMO, a top Russian university of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs), and presented to the Government for Cross-Border Cooperation (GCC). The introductory section describes how Russia and Belarus, referred to together as a Union State, must resist the “storm of sanctions” imposed on them by the West and how the Union State must have the sovereign right to decide its own destiny and build a peaceful future.

It then goes on to describe the format of the Baltic Platform, and how it is aligned with “a more effective fulfilment of the foreign policy objectives set by President Vladimir Putin.”

To this end, according to the document, it is necessary, among other things, to “identify problematic (non-political) areas of interaction that require joint efforts in connection with the changed international situation and increased threats to the Baltic macroregion.”

The authors of the document, including both IMEMO Director Fyodor Voitolovsky and MGIMO Institute of International Studies Director Maksim Sutskov, have already identified one such area. According to their approach, the Baltic Platform will address the “immediate and urgent challenges” of “the anthropogenic and climate-related threats to the Baltic Sea, the environmental degradation of the Baltic Sea ecosystem and the need to reduce the consequences of the militarization of the region.”

“Of all the possible avenues for humanitarian cooperation between Russia, Belarus and the Baltic Sea states, in the current geopolitical turbulence and amidst Western sanctions, perhaps only one can be identified which is of interest to all or most of the countries in the region and which, at the same time, is not irreversibly politicised. This is the ecology of the Baltic Sea,” the authors conclude.

Among other things, this will require, according to the plan, the creation of opportunities for cooperation with organisations, movements and institutions in the Baltic States that are concerned with precisely such issues.

Through climate and environment topics to geopolitics

In another accompanying document, the logic of the Baltic Platform is described as “a progressive transition from the discussion of non-political topics to current political topics, with a gradual increase in the complexity and severity of the issues raised.”

The main document points out that environmental issues specifically can be dramatized. “This means hyperbolization of individual problems and creating new ones, modeling catastrophic scenarios in order to call for a dialogue,” the paper says.

Aleksander Toots, deputy director general of the Estonian Internal Security Service (KAPO), said the KAPO had seen Russia use environmental themes in influence operations before. “Russia is trying to make use of topics that regular people care about. Climate and environmental issues are a good example of it,” Toots said.

The Baltic Platform operation is also seen as a way to bring Belarus to the table: although the totalitarian country has no outlet to the sea, the Belarusian rivers Nemunas and Western Dvina flow into the Baltic Sea. “And the rivers pose a significant pollution risk. This means there is something to discuss,” reads the document.

“The biggest potential is to have a dialogue on how to preserve biological diversity in the Baltic Sea and the problem of its industrial and other anthropogenic pollution,” the paper says. The paper points out that these issues can be addressed in cooperation with organizations such as the Baltic Sea Centre at Stockholm University and the Helsinki Commission, or HELCOM, which was set up specifically to protect the Baltic Sea.

Tina Elfwing, Director of the Baltic Sea Centre at Stockholm University, said that the Centre had not yet been approached with such a plan or invitation. “It is so damn upsetting and unpleasant to be listed in such a document. At the same time I think that if you want to launch something called the Baltic Platform to deal with the Baltic Sea and the environment, then it is logical to approach our center,” said Elfwing.

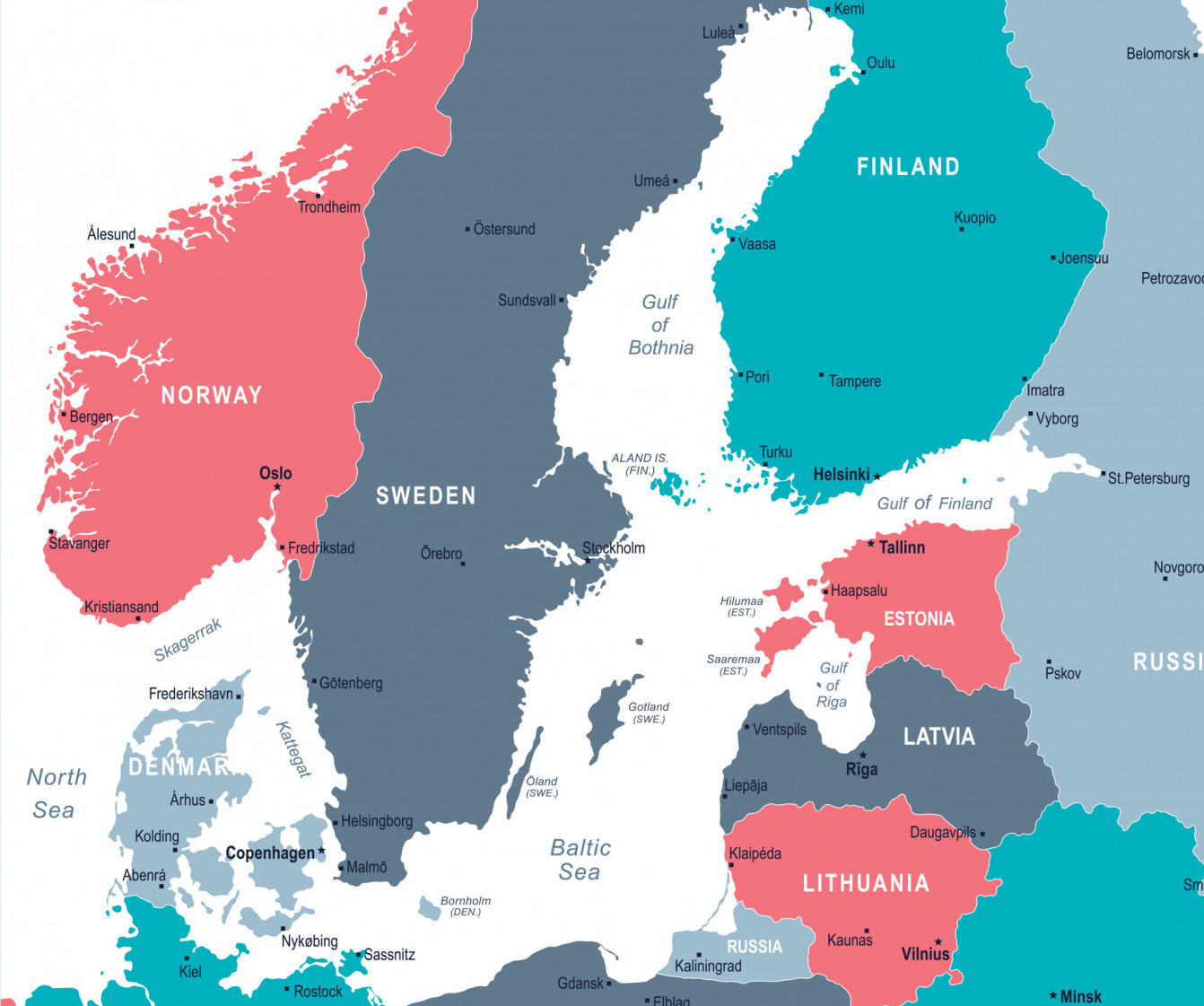

Baltic Sea Area Map. Source: Shutterstock

Much of what the Russian document says about the health of the Baltic Sea is right. According to Elfwing, the situation in the Baltic Sea is very serious because it is a shallow and enclosed sea with extremely narrow access to the ocean. This is why pollution persists for longer than it does in the open seas.

“There are 85 million people in the combined catchment area. It’s a huge land area that drains into the Baltic Sea and then the water takes with it what it finds on the way, which can be nutrients and environmental toxins, and which then end up in this shallow little tub.”

Elfwing said that, if they had been approached before the journalists’ inquiry, her centre would not have accepted the invitation because they are doing research and don’t have time for simple dialogue. However, she acknowledged that there could be enough naivety among environmental scientists, whose day-to-day work is far removed from military-strategic issues, to not understand the background to the invitation.

The use of environmental themes and other seemingly benign issues is, according to Toots, one of the old and much-used methods to legend contacts and to get an adequate overview of a particular area of interest.

“In other words, it’s one of the ways of gathering information that ultimately gives a better picture of the situation, and it has been used consistently. It is important to understand that this is not done by officers of the Russian intelligence services, but by their agency. They have the necessary education, together with specialist knowledge, and they know how to do their job. They have contacts with specialists. Using this approach, they can collect information under a specific cover in different countries. Later on, the intelligence service will decide when and how to make the most efficient use of it,” Toots said.

At the outbreak of the war, the Helsinki Commission declared a “strategic pause.” This meant suspending all cooperation with Russia, which had formally acceded to the convention on which the Commission was founded. In a written reply to journalists, HELCOM confirmed that the pause continues to this day.

The document we obtained is accompanied by a timetable for setting up the Baltic Platform. According to the timetable, the period from January to March of this year was spent “setting up the organizing committee,” finding suitable opinion leaders and drafting key documents. “In setting up the steering group of the organizing committee, the focus must be on ‘old’ Europe, i.e. Germany-Scandinavia (and not the Baltic States of the three former USSR republics),” the guidelines state.

The document is also accompanied by a list of Russian names—people who might be suitable for the organizing committee. These include the governor of Kaliningrad oblast and the rectors of several universities. When we phoned the Rector of St Petersburg State University, Mr Kropachov, whose name is on the list, he confirmed the existence of the Baltic Platform and referred us to the Vice-Rector for International Relations at the university.

Our colleagues from the Dossier Research Centre wrote to the Vice-Rector pretending to be Swedish environmental activists, and they, in turn, received a reply from the Vice-Rector’s Adviser for External Relations. “I am currently working on the preparation of the Baltic Platform project. I will be happy to answer your questions,” the letter said. However, we did not receive answers to further questions, but this may have to do with the fact that, at the time we sent these questions, we also sent a formal request for comment to the Kremlin. We did not receive a reply to that either.

Baltic Sea under attack

At the same time as the creation of the organizing committee, the Kaliningrad press was to start “pedaling catastrophic forecasts of the unstoppable growth of threats to the Baltic Sea and the Baltic ecosystem” and, among other things, to start pushing “new key terms.” For example, the guidelines suggest that the Russian word “Pribaltika” no longer be used, and that it was to be replaced with the more neutral “Baltic Sea Region” or “Greater Baltic Sea Region,” which is more familiar to Europeans.

In describing which opinion leaders should be brought together, the document focuses on Germans and Scandinavians and “Baltic Russians” alongside Russians and Belarusians. The aim of this phase is to “bring together non-political, scientific and cultural interest and create a common platform to ‘save’ the Greater Baltic region from growing climatic and man-made threats, including the growing militarisation of the region.” In doing so, the authors of the document have pointedly put the word “save” between quotation marks.

In March, the Baltic Platform was due to become more public, with representatives attending a series of “scientific hands-on events” at St Petersburg State University, MGIMO and IMEMO, the Russian Academy of Sciences and elsewhere. At the same time, European opinion leaders, scientists, cultural and religious figures were to come into play to “solve the region’s problems.”

At the end of the very last column of the launch timetable, there is a description of where the launch of the Baltic Platform should be by March:

“An exit to the ‘main task’: the Russians are against the militarization of the Baltics and in favor of a peaceful, good-neighborly and mutually beneficial solution to the region’s problems.”

The “main task” is scheduled to start this autumn, when the first six sessions of the Baltic Platform are scheduled to be held.

VSquare found that Russian media did indeed start to write about the health of the Baltic Sea in March. For example, the online portal Smotrim.ru, which brings together a number of Russia’s state TV channels, reported that the Nord Stream gas pipeline would lead to a risk of chemical pollution in the Baltic Sea. The state news agency TASS, for its part, reported that the restoration of the Baltic Sea environment could become part of Russia’s national programme by 2025. Meanwhile, GTN Pravda, a municipal newspaper in the Leningrad region, wrote that Russia’s western regions were joining forces to save the ecology of the Baltic water system.

Alexander Dynkin, President of the Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg International Economic Forum 2021. Source: Maksim Konstantinov / Russian Look / Forum

To top it all off, “Baltic Sea Day” was celebrated in St Petersburg on 22-24 March, along with the international forum “Ecology of the Big City.” According to the event’s website, its main objective was to “to promote and introduce innovative environmental protection equipment and technologies that help conserve natural resources, strengthen environmental safety and improve the quality of life in large cities.”

Two different sources, one of whom is a European intelligence officer, confirmed to us that the Baltic Platform’s work plan included a list of Western experts who were or are wanted to be involved. Such experts included the former Swedish ambassador to Moscow, Sven Hirdman, and Markku Kangaspuro, director of the Alexander Institute at the University of Helsinki.

When Hirdman resigned as ambassador to Moscow in 2004, Putin rewarded him with the Order of Friendship for his efforts in developing relations between the two countries. He then served on the MGIMO Council for five years. MGIMO Rector Anatoly Torkunov, whom Hirdman says he knows “quite well,” is also a potential member of the Baltic Platform’s steering committee. “I haven’t heard anything about this particular project and certainly no one has approached me about it,” he said.

Kangaspuro, who runs an institute for Russian, Eurasian and East European studies at the University of Helsinki, is also known in Finland as an active anti-NATO activist. He is chairman of the “Finnish Peace Defenders” movement. Last May, the “peacekeepers” organized a rally in Helsinki called “No to NATO, yes to peace.” Kangaspuro took part with a speech.

Kangaspuro told VSquare that he had not heard of the Baltic Platform and could not say why his name had been put on the list of potential foreign experts. “I had contacts with St Petersburg State University before the war, but not since. Maybe they added my name because they had previous contact with me,” he said.

Baltic Platform – a “fishing expedition”

Baltic intelligence and counterintelligence agencies contacted by the daily and our other partners for comment on the Baltic Platform pointed out that Russia had used similar tactics handwriting before. In a written reply, the Latvian Constitutional Defence Bureau (SAB) noted that in the past, the Kremlin’s fingerprints were visible from afar in such activities, given away by the citation of well-known pseudo-experts and discussion of subjects mainly of concern to the Kremlin, such as Russian language rights in the Baltic states. But this strategy no longer works.

“That is why the Russian Presidential Administration is creating a project in which the traces of the Kremlin will be more skilfully hidden. Among these plans is the search for Western partners. Climate and environmental policy issues, which Russia can position as a mutually beneficial direction of cooperation, are one of these potential points of contact,” the SAB said.

Marius Laurinavičius, a Lithuanian security analyst, calls such activities “fishing” expeditions, and notes that other similar forums are organized to connect with different opinion leaders. “They’re interested in getting in touch with scientists and climate change or environmental activists to understand their way of thinking and then make decisions as to which of them could be used for Russian influence operations, if not recruited as Russian agents.”

Darius Jauniškis, director of the Lithuanian National Security Service (VSD), said that Russia is looking for experts, scientists, NGOs from Western countries and offers them cooperation on seemingly neutral issues such as science and environmental protection. “Russia wants to promote the idea that cooperation with Russia is necessary regardless of its aggression in Ukraine and that the isolation and sanctions are harmful to European countries,” said Jauniškis.

The text was written as part of an international collaboration

The text was written as part of an international collaboration

of VSquare and FRONTSTORY.PL with:

Delfi Estonia,

Expressen,

Kiyv Independent,

Yahoo News,

Süddeutsche Zeitung,

Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR),

Dossier Center,

NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk),

Re:Baltica,

LRT

Head of the investigative desk at Delfi Estonia, Holger Roonemaa has extensively investigated topics related to national security, including Russia’s espionage, interference, and influence operations in Estonia and the wider region. He is a member of the International Consortium on Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Estonia’s national media association named him the journalist of the year in 2020 and 2021.