Anna Gielewska (VSquare)

Illustration: Karl-Erik Leik (Delfi Estonia) 2023-03-14

Anna Gielewska (VSquare)

Illustration: Karl-Erik Leik (Delfi Estonia) 2023-03-14

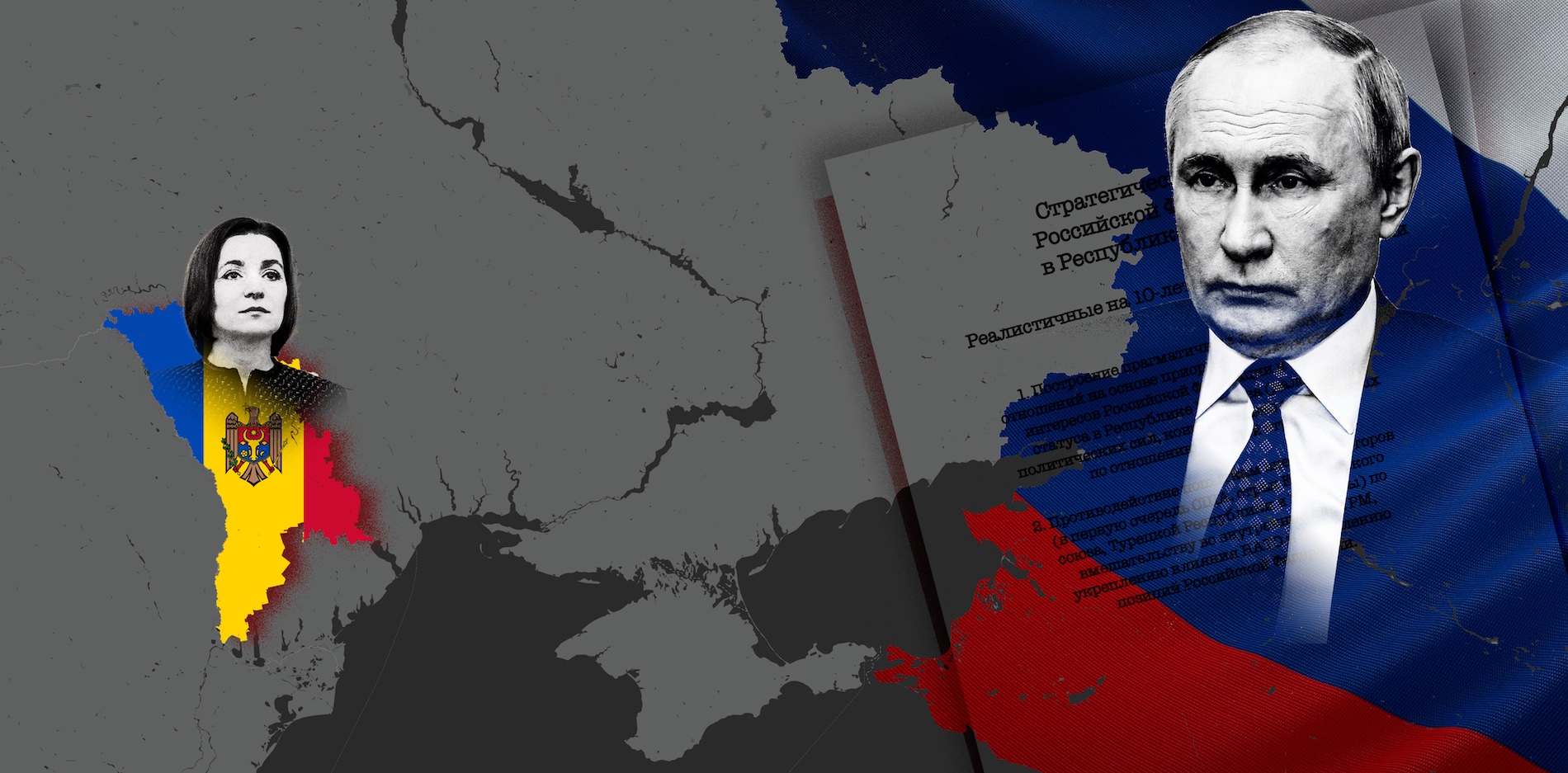

How to make a satellite state out of an independent Moldova? Russia has a ready-made plan: to support pro-Putin politicians, activists, and the Orthodox Church; to make the country dependent on gas; to discourage the EU and NATO; and to stir up social conflicts.

The hybrid war scenario, written in a leaked Kremlin document, is underway.

VSquare has obtained a document in which Vladimir Putin’s henchmen reveal their plans for overthrowing Moldova’s pro-Western government and regaining political control of the country. It is part of a broader strategy prepared in 2021 for the Putin administration.

In February, we revealed a similar document on Belarus that envisions that country’s annexation into a Union State with Russia by 2030.

Now we have evidence that Russia prepared a similar plan for Moldova. This time, Russia would take back control not by annexation, but through hybrid warfare. The strategy includes forcing Moldova’s government to give up attempts to influence Transnistria (a self-proclaimed state supported by Russia); supporting political forces friendly to the Russian Federation; and maintaining the country’s dependence on gas supplies from Russia.

The strategy also mentions setting up Moscow-friendly NGOs, as well as countering “Romanization,” that is, cutting Moldova’s ties with neighboring Romania, a member state of the European Union and NATO. The importance of discouraging Moldovans from joining NATO and the European Union is stressed several times in the plan.

The internal document was obtained by VSquare and Frontstory together along with several international partners: Delfi Estonia, the Swedish newspaper Expressen, the Dossier Centre for Investigative Journalism, the Ukrainian newspaper Kyiv Independent, RISE Moldova, the German newspapers Süddeutsche Zeitung and Westdeutscher Rundfunk, and the US news channel Yahoo News.

After we previously revealed the strategy towards Belarus, Belarusian dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko admitted on camera that the Kremlin document may indeed have existed, but said that he saw the publication as an attempt to split Russia and Belarus.

The document on Moldova was created in 2021 in the same department that drew up the strategy for Belarus, that is, in the Directorate for Cross-Border Cooperation. By Putin’s decree, that department began dealing with the “European direction” in August 2021. Its tasks include informational and analytical support to the presidential administration, and also participation in “the preparation of proposals relating to the improvement of activities for the implementation of projects and programs to assist international development in the economic, political and humanitarian spheres.” The strategy for Moldova, like the one for Belarus, lists exactly such areas. The documents have reached the desk of Dmitry Kozak, deputy head of the Russian presidential administration, among others.

In October 2020, the London-based Dossier Center identified four people dealing with Moldova in this unit. We managed to identify another one: according to our sources in western intelligence, the main author of the document is department counsel Andrei Vavilov, a graduate of the FSB academy (he spent almost a decade in the service afterwards).

❗ According to our sources in western intelligence, the main author of the document is department counsel Andrei Vavilov, a graduate of the FSB academy. One RISE Moldova journalist called Vavilov on the eve of releasing the investigation.

Read more: https://t.co/zr4EtyzaxH pic.twitter.com/lyJZK0zl7d

— VSquare (@VSquare_Project) March 14, 2023

One RISE Moldova journalist called Vavilov on the eve of releasing the investigation. They reached one of Vavilov’s phone numbers. After hearing his last name and answering the greeting, the man on the other end of the line clarified:

– Who is speaking?

– This is Vladimir Thorik calling. I’m from Moldova.

– What is your question?

– I’m a journalist at RISE Moldova. I have a question about a document concerning cooperation with Moldova. We have a document titled: “Strategic goals of the Russian Federation…”

– You have the wrong number…

It appears that Vavilov, reached for comment, did not want to talk.

Last Friday, the White House issued an official warning that Russia is seeking to destabilize Moldova’s pro-Western government and wants to install a new leadership in the country. Two days later, Moldovan police arrested several protesters, claiming they had been sent and paid by Russia to destabilize the country. Moldovan border guards detained an alleged mercenary from Russia’s Wagner Group at the border.

Kremlin Playbook

The document, titled “Strategic objectives of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Moldova,” is a plan for hybrid warfare. According to this document, Russia wants to make Moldova a satellite state by 2030. The roadmap for “realistic 10-year goals” provides “countering the attempts of external actors (primarily the United States, the countries of the European Union, the Republic of Turkey and Ukraine) to interfere in the internal affairs of the Republic of Moldova, strengthen the influence of NATO and weaken the positions of the Russian Federation.” Russia’s targets are divided into short-term (by 2022), medium-term (by 2025) and long-term (by 2030).

As short-term goals, the document lists, among others:

– neutralization of the initiatives of the Republic of Moldova aimed at eliminating the Russian military presence in Transnistria

– opening of the Consulate General in Comrat, the capital of Gagauzia

– neutralization of attempts to limit the activities of Russian and pro-Russian media in Moldova

– creation of a network of NGOs promoting the development of Russian-Moldovan relations.

The medium-term goals (through 2025) include:

– expansion of the electoral base of Moldovan political forces advocating constructive relations with the Russian Federation

– countering Moldova’s cooperation with NATO.

– ensuring the sustainable functioning of the system of organizational, financial, legal and information support of NGOs friendly to the Russian Federation.

By 2030, Kremlin has planned for the “creation of stable pro-Russian groups of influence in the Moldovan political and economic elites”; “the formation of a negative attitude towards NATO in Moldovan society”, and supporting the Russian Orthodox Church in defending the interests of canonical Orthodoxy in the Republic of Moldova”.

Marc Polymeropolous, former head of European and Eurasian Operations at CIA, offers: “Moldova remains in the crosshairs of Moscow. While the Russian goals are not earth-shattering, the clear operational mandate with a strategic framework and timelines demonstrates an active measures program designed to influence the internal affairs of Moldova both in the short and long term.”

According to the Western intelligence officer familiar with the document, “It is almost certain that this paper is being used in the Kremlin as the main work plan for Moldova.”

Hybrid war in the tent

Last Sunday, images of anti-government demonstrations in Chisinau were popping up in media outlets around the world. Moldovan police detain more than 50 protesters.

Demonstrates gathered at the capital, Chisinau, to rally against the rising costs on Sunday, 12 March 2023. Source: Anna-Karin Nilsson / Expressen

Moldova, squeezed between Romania and Ukraine, has been living in a state of emergency since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but since last autumn, Russia’s hybrid war against Europe’s poorest country, which has a population of 2.6 million people, has taken on unprecedented proportions.

The country turned westwards in 2020 when Maia Sandu ousted President Igor Dodon. Dodon was backed by pro-Kremlin oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc. Dodon, as the 2020 Dossier Center report revealed, reported and coordinated with a Kremlin office led by former SVR officers.

In the summer of 2021, the pro-Western PAS party won a majority in parliament and strengthened the course toward the European Union. The Kremlin found itself in a new situation, suddenly losing its customary power and envisaging a new strategy on how to bring the “runaway child” back home. Perhaps that is why the summary at the head of the document is subtitled “realistic goals” and lacks the Kremlin’s characteristic over-ambitiousness.

Krzysztof Lisek, program director of the Moldovan branch of the International Republican Institute, has been based in Chisinau since the summer of 2021. “Hybrid measures intensified in the summer of 2022, a few months after the outbreak of war in Ukraine. The first culmination was in the fall of 2022 when ‘the anti-government tent city; was launched. The second happens right now—with weekly protests led by the pro-Russian party Shor, recently very active.”

The party is headed by Ilan Shor, a pro-Kremlin oligarch accused of stealing billions of dollars from Moldovan banks in 2014. Today, Shor is wanted in Moldova, and is said to be hiding in Israel. The US placed Shor on the list of sanctions in October 2022. According to the US Treasury Department, the oligarch was part of a Russian plan to weaken Moldovan President Maia Sandu ahead of the 2021 elections. “Shor worked with Russian individuals to create a political alliance to control Moldova’s parliament, which would then support several pieces of legislation in the interests of the Russian Federation.” According to the Treasury Department, Shor continued to receive Russian support in June 2022, and his party was coordinating with representatives of other oligarchs to create political unrest in Moldova—for example, by drawing protesters to more demonstrations.

“It was already demonstrated that these protests are paid and the participants of the protests—people from low societal level—are paid to come there. Due to their very scarce economic situation for 10 euros they are ready to be there and protest,” Elena Mârzac, a Moldovan security analyst, tells Delfi and Expressen reporters.

Media report similar rates for participation in demonstrations. According to Deutsche Welle, about €20 for a regular protest and €80, given in cash, for a night in a tent city.

Shor party organizes buses to bring demonstrators to Chisinau. As Krzysztof Lisek tells it, quite a few people are coming from the small town of Orhea, a town where Ilan Shor has built an amusement park and cleaned up a lake: “Solicitors are even standing outside schools, encouraging teenagers to participate in demonstrations. Now they are collecting signatures to call for the dissolution of parliament and early elections. Especially for elderly solicitors, this is often a way to add to a very low pension. The question is, who pays for all this?”

In the summer of 2022, the Moldovan Prosecutor’s Office opened an investigation into illegal funding of the Shor party. Moldovan law does not allow party funding from abroad. On the same day, Marina Tauber, the vice president of the party, was arrested. After her release from detention, she continued her actions.

Marina Tauber leads demonstrates gathered at the capital, Chisinau, on Sunday, 12 March 2023. Source: Anna-Karin Nilsson / Expressen

Last Sunday, she led another demonstration in the capital.

“We want to oblige our government to pay the bills for heating, electricity and gas for the three winter months, December, January and February, for all our citizens. We know that we have money from our development partners that have allocated to us more than 1 billion euro in the last two years and then 250 million euro only this year, so we want this money to be directed for paying the bills because our people don’t have money and don’t have possibilities to pay these bills,” Marina Tauber, told to Expressen reporter. She denied that Russia is helping to organize or fund the protests.

“There is growing public discontent in Moldova due to rising prices, inflation, a 6-fold increase in gas tariffs, and several-fold increases in energy prices. Polls, which are conducted quite regularly, show growing dissatisfaction with the government’s actions,” explains Kamil Całus of the Warsaw-based think-tank Center for Eastern Studies.

However, he stresses, protests organized by Shor are relatively few in number. “At their peak, they reached some 10,000 people last fall. This shows that despite the public discontent, which is genuine, Moldovans do not want to participate in them en masse.”

Last Monday, Krzysztof Lisek landed at Chisinau airport: “Right in front of me landed a group of Shor activists, flying in from Istanbul. They were separated by a cordon of police. Allegedly, as reported by the media, they trained Turkey on how to organize protests. But they told the media that they flew in for a course in making kebabs.”

Lenin monument

Gagauzia is perhaps one of the most pro-Russian regions in Moldova, alongside Transnistria. The main street of the territory’s capital, Comrat, bears the name of Vladimir Lenin. A bronze statue of Lenin stands in front of the administrative building. On the opposite side of the street, there’s the most impressive building of the town: a bright yellow Orthodox church with golden domes shining in the early spring sun.

A few minutes walk away, up a small hill, there’s a statue park where a children’s playground is packed in between an eternal flame in the honor of the participants of the “Great Patriotic War”—Russia’s name for World War II—and other Soviet era monuments that commemorate, for example, the heroic border guards of the Soviet Union.

“As long as Lenin is here, the Soviet Union will also be in people’s minds. Yes, we even have a Dzerzhinsky Street, I apologize for the swear word, but what the fuck. That’s a shame, what the hell, Dzerzhinsky,” says local reporter Petru Garciu, who gets irritated as he talks to us under Lenin.

According to Garciu, about 80 percent of Gagauzans are pro-Russian. “For many of them, for example those born during the Soviet era, the USSR is [still] their homeland. The USSR is something sacred. For them, the USSR and Russia are like a father and a father cannot be a killer.” Garciu tries to explain why people here tend to believe that “Russia will liberate Ukraine from the Nazis.”

The Kremlin’s strategy document specifically mentions Gagauzia as an area where Russia aimed to open a consulate as early as 2022. In 2021, a local “activist”’ started collecting signatures of support to present to Putin for the opening of a consulate; so far, Moldova has not promised to open one.

According to Indrek Kannik, director of the International Centre for Defence Studies and former head of analysis at the Foreign Intelligence Agency, Russia has been considering turning Gagauzia into a “second Transnistria” but has yet to take it that far. “Russia has a lot of traction in Gagauzia which means that they have an extended ability to destabilize the region. They have indeed been destabilizing [Gagauzia] but they haven’t seen the necessity to put on full throttle so far,” he said.

The Gagauz people, as Petru Garciu describes, are Orthodox, and are very religious and devout. “They will take the last money to church, even if they don’t have enough money for themselves, but they will. And this influence of course will, is making itself felt. For them, Patriarch Kirill is something sacred,” says Garciu.

The strategy document specifically identified the need to strengthen the position of the Russian Orthodox church in Moldova by 2030.

For security expert Elena Mârzac, the church is not there to only take care of the people’s souls.

“[Russia] has been using the Orthodox Church in Moldova throughout our independence as an instrument to convey its messages, to manipulate and amplify the idea of Moldovan-Russian cooperation. Even during the 2020 presidential elections, when Igor Dodon ran against Maia Sandu, the church was used to discredit Sandu. Why? Because, according to sociological surveys, the church is the most trusted public institution,” says Mârzac.

Mârzac, who studied Russian hybrid war instruments against Moldova for years, almost started laughing when Delfi and Expressen reporters showed her the Kremlin’s strategy. “All these years, it was very difficult to understand what exactly was our government’s position [on NATO], and now, reading this document, I understand really well that yes, the Russian Federation worked very well in Moldova. All the elements I wrote down here— political parties, Transnistria, economic element, humanitarian sphere— everything is present here in this plan. I even see that there is a goal until 2025 to counteract the cooperation of Moldova with NATO. And they did this all these years!”

Ban on propaganda

In Gaugazia, Russian propaganda media still operate. The government has not blocked them as in the rest of the country, where Russian stations are no longer operating on cable—the result of a ban introduced after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The morning of International Women’s Day, March 8, is slow and lazy in the governmental district of Chisinau, the capital of Moldova. It is a national holiday. A bomb dog and his handler take a careful round around a huge Soviet-era government office building, carefully sniffing every small corner.

There is definitely a heightened sense of security. The carabinieri are quick to come check the small group of people waiting in front of the building to be accompanied inside. Because of recent security alerts, the border guards now ask all the reporters who arrive in Chisinau to apply for special accreditation.

“I would be very happy if people in Moldova see this document,” Sergiu Diaconu, the chief of staff of the freshly-appointed prime minister Dorin Recean, says as he reads the secret Kremlin document handed to him by the reporters.

It’s not so much that the content of the document shocks or surprises Diaconu. Rather the opposite. Diaconu, like many other Moldovans, has long witnessed everything that the Kremlin’s strategy represents in real life. The value of the document lies in the fact that the Kremlin’s real objectives are now painted in black and red by them: for example, the use of energy, mainly natural gas, as a lever of influence. Moldova has been totally dependent on Russian energy for decades, and it is only in the last year that it has been able to take the first steps towards breaking this dependence.

Midway through the conversation, prime minister Recean enters the meeting room to give his opinion on Russia’s strategy and how his government thinks it can counter it. Recean was appointed to the post only this February after the former prime minister, Natalia Gavrilita, resigned under the pressure of extensive street protests—organized and funded by strongly pro-Kremlin actors. Unlike Gavrilita, Recean is experienced in defense and security issues, having earlier served as the minister of internal affairs as well as an advisor to president Sandu on defense and national security, and as the secretary of the Supreme Security Council.

Prime Minister Dorin Recean during interview with Holger Roonemaa, Mattias Carlsson and Liliana Botnariuc. Source: Anna-Karin Nilsson / Expressen

“Militarily Russia can’t advance,” Recean says. Instead, he identifies the hybrid war as the main risk that Russia poses on the much smaller country.

“Last year, for example, we had up to 80 false bomb alerts. This is obviously inducing anxiety into the society and on the background of the anxiety you can promote a lot of false narratives,” Recean says. “And then obviously they are co-financing these protests and attempts to destabilize [the country]. They are looking to recruit tough guys in order to attack police, in order to attack government buildings and companies and make these kinds of provocations that would lead to destabilization. This is what they are trying to get.”

Such active measures are often followed by propaganda amplifying the events.

For example, last week, when Transnistrian authorities announced arresting an alleged terrorist who had intended to blow up his Land Rover filled with 8 kilos of explosives on the main square of the region’s capital Tiraspol and assassinate the local leader Vadim Krasnoselski along the way. It was the openly pro-Russian former president Igor Dodon who instantly took to Russian media and amplified the probable false-flag event by demanding the Moldovan authorities “take measures against the involvement of the country in the conflict in Ukraine.”

Transnistria is one of the so-called frozen conflicts in the region between the east bank of the Dniester river and the Moldovan-Ukrainian border. In reality, Moldova has little control of the region. Transnistria is also home to hundreds of Russian troops officially described as “peacekeepers.” These “peacekeepers” have been the cause of military threat to Moldova since the 1990s. As well they have been keeping the pressure on Ukraine with a possibility of Russia opening a new line of attack across the Moldovan border on the Odessa region.

“[For years] we didn’t pay attention to propaganda and Russian TV. And when we started to act, the propaganda moved to Telegram, Facebook, Vkontakte, TikTok. With Telegram and TikTok we cannot do anything about it except cut the wire. 30 something years of propaganda, we see [the effect of it] now,” Recean says.

He admits that even the pro-Western governments have not found a way to counter Kremlin’s propaganda. Today, with inflation above 34 percent, convincing people of the benefits of European integration is even more difficult. There is also a growing sense of threat of war in Ukraine.

“And when people fear, they say, okay, the ‘Russian bear’ is too big for us. Maybe we can get a kind of understanding and agreement with the Russian bear and they won’t touch us,” Recean says.

Holger Roonemaa, Mattias Carlsson and Liliana Botnariuc interview Oazu Nantoi. Source: Anna-Karin Nilsson / Expressen

Oazu Nantoi is a member of the Moldovan parliament’s committee on national security and defense. “Moldova is under a strong hybrid attack from Russia. And the range of tools used by the Russian Federation is a mirror image of our weaknesses,” says Nantoi. From his narrow office, he has a direct view of the presidential building, with the last of the evening sun reflecting off the upper floors.

Nantoi explains that the Moldovan parliament has passed several laws to combat propaganda, but it is difficult to find a solution, adding, “We cannot follow the North Korean strategy, we have freedom of speech, freedom of opinion. It is a challenge for us.”

Moldova’s next presidential election will be held next fall. A year later, parliamentary elections.

The Western intelligence officer says that the Kremlin is behaving more and more aggressively in Moldova because Moldova “is currently on the opposite course to what Russia wants. The Moldovan leadership has taken a clearly pro-Western course. Thus, the Kremlin’s strategic goals are becoming more difficult, not easier, to achieve over time. The Kremlin understands this, therefore they have steadily increased the pressure and are using more aggressive tactics to realize these goals.”

According to Oazu Nantoi, the only real guarantee of Moldova’s security is Russia’s political and military defeat in Ukraine.

“The price is terrible,” Nantoi says, “and it is paid by the Ukrainian people.”

The text was written as part of an international collaboration with: Delfi Estonia, Expressen (Sweden), RISE Moldova, Kyiv Independent, Yahoo News, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) and Dossier Center.

Anna Gielewska is co-founder and editor-in-chief of VSquare and co-founder of Polish investigative outlet FRONTSTORY.PL. She is also vice-chairwoman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). A journalist specializing in investigating organized disinformation and propaganda, Gielewska was the John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2019/20) and has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2015, 2021, 2022) and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Award (2021, 2023). She was the recipient of the Novinarska Cena in 2022.