Illustration: Lenka Matoušková 2025-11-13

Illustration: Lenka Matoušková 2025-11-13

Ahmed Ghorab is a computer scientist who, thanks to a student foundation, managed to leave war-torn Gaza. However, his family remained there. He promised to bring them to Europe. Instead, he encountered harsh Slovak bureaucracy, which he has been fighting for more than a year. In the meantime, the mental and physical health of his children have significantly deteriorated.

Ahmed Ghorab taught information technology at the University College of Applied Sciences (UCAS) in Gaza and coordinated international academic projects. As a computer scientist, he specialized in neural networks, artificial intelligence and image processing. Among the projects he collaborated on was the automated diagnosis of glaucoma (green cataract). He had a good life in Gaza, playing football with colleagues on the beach on Fridays, buying a car for his wife, and furnishing the children’s rooms down to the smallest detail. “I was just finishing my doctorate, I had passed all the exams and was about to start my dissertation,” Ahmed says, explaining his situation at the time in perfect English.

Ahmed Ghorab, a computer scientist from the Gaza Strip, now lives in Slovakia. For more than a year, he has been trying to get his family out of the war zone and to safety. Source: Ahmed Ghorab (private archive).

He never finished the intended dissertation work. Today, he lives on the outskirts of Bratislava, where he devotes all his free time to trying to get his wife and four malnourished and traumatized children out of Gaza.

Ahmed and I met in a café not far from where he lives. Although it was quite cold that summer day, he kept wiping his sweaty forehead with a handkerchief. It was clear that he was not used to talking to journalists and was uncomfortable returning to traumatic memories: to the moment he managed to leave the Gaza Strip, while his family, which he is still unable to save, remained there.

“We Haven’t Slept for a Week”

In Gaza, Ahmed’s family lived in one of the city’s tallest buildings. It was clear that they would not be safe there when the war broke out. “We lost our home to the bombing exactly twelve days after the war started,” he recalls of the destruction of the house where he and his family were fortunately no longer living at the time of the airstrike. They were living with their in-laws in the safer Deir al-Balah area in the middle of the Gaza Strip.

The house in Gaza where Ahmed Ghorab and his family lived until October 2023. Their apartment was on the top floor (left). On the right is the same house after it was destroyed by Israeli bombing twelve days after the outbreak of war. Fortunately, the family was not at home at the time of the attack. Source: Ahmed Ghorab (private archive).

In mid-December 2023, the family gathered for dinner. It was one of the quieter days. “After dinner, we were all sitting in the living room, just before we went to bed. My family was there, my brother-in-law’s family, and my wife’s parents. We had already put most of the children to bed in the next room, where they finally fell asleep. And suddenly three bombs fell,” Ahmed says, describing a night he will never forget. “The bombs fell on the house directly across the street, not even ten meters from us. The four-story building was completely destroyed, and twenty-five people died on the spot.”

Immediately after the bombing, Ahmed went across the street to help rescue people and clear away the rubble. The blast wave also hit the house where his family lived, damaging the walls, windows and facade. “The worst thing was that there were human remains lying all around us. For the first time in my life, I held a disembodied human head in my hands. It was a woman. There were three dismembered human bodies lying right in front of our house. It was horrible, cleaning them up. Of course, we forbade the children to leave the house so they wouldn’t see it. Only the oldest one helped to clear away the aftermath of the bombing. None of us slept for a week.”

The house where Ahmed and his family were preparing to sleep when it was damaged by the shock wave from the bomb. His family still lives there today. Photo: Ahmed Ghorab (private archive).

A Tough Dilemma

“I couldn’t take it anymore. The only thing I could think of was the possibility of registering as a doctoral student on a student portal that helped students and their families evacuate from Gaza,” he explains. At that time, leaving the Gaza Strip was only possible through the heavily guarded Rafah border crossing on the Egyptian border.

But Egyptian authorities refused to let Ahmed’s wife and children cross the border until they paid a “coordination fee” of $5,000 per person, or almost half a million Czech crowns for all of them. The fee was collected by the Egyptian travel agency Hala Consulting and Tourism, and had to be paid at the time by anyone who wanted to get from Gaza to Egypt. The agency belongs to Egyptian businessman Ibrahim Al-Argani, who has close ties to the Egyptian secret services and the Egyptian president.

We explored the collection of special fees for crossing through Rafah in greater detail here.

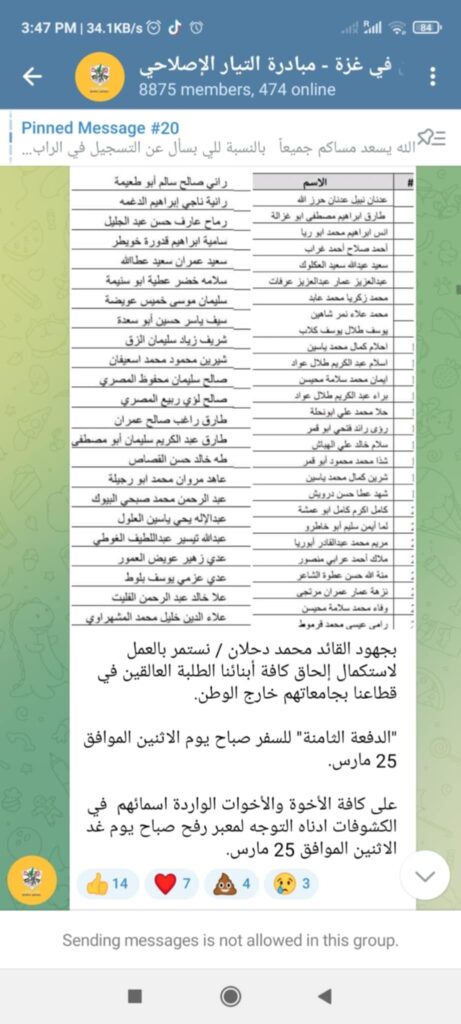

His family couldn’t afford that kind of money. So Ahmed decided to stay in Gaza. “But my wife didn’t agree and insisted that I had to leave. That it was our only chance to start a new life somewhere else,” he adds. Mohammed Dahlan’s student organization offered to help him and paid the $5,000 for him. Thanks to that money, Ahmed was put on an unofficial list of people who could cross the Rafah border crossing into Egypt. His departure was coordinated through a Telegram group.

When Ahmed left the Gaza Strip in March 2024, he first headed to Cairo. There, he tried to raise money to get the rest of his family to safety. He also registered his loved ones on the official list of people Egypt was supposed to help evacuate from the war zone of Gaza. In the meantime, however, the Rafah crossing had been permanently closed.

An unofficial list of people waiting to be evacuated from Gaza to Egypt, circulated via the Telegram app. Ahmed’s name is also on the list. Source: investigace.cz.

From Gaza to Egypt, from Egypt to Belgium, from Belgium to Slovakia

In March, Ahmed decided to leave Egypt for Belgium, where he has friends and relatives. He landed at the Belgian Zaventem airport on April 1, 2024. “I applied for asylum right at the airport,” he says of the first moments after landing. However, after eight weeks, he had to leave Belgium and move to Slovakia. And this meant the matter of his family was no longer up to Belgium: According to the Dublin Agreements, the asylum procedure for applicants is to be handled by the country that granted him a Schengen visa. That country was Slovakia, which issued Ahmed an entry visa to the Schengen area as part of academic cooperation with the Slovak University of Agriculture (SPU) in Nitra.

Inter-university cooperation on projects related to the use of information technologies in agriculture in the Gaza Strip was also confirmed by PhDr. Renáta Chosraviová, spokesperson for the SPU.

Ahmed continued his application for international protection in Slovakia. After arriving, he spent three weeks in a refugee camp in Humenne and another two months in an accommodation center in Rohovce. Ahmed obtained Slovak documents authorizing him to stay in the country and travel around Europe in early September 2024.

But the bigger problem concerned employment. “I went to a lot of interviews, but I always ended up saying I didn’t know Slovak,” he explains, adding: “The one hour of tuition per week provided by the state for the integration of foreigners is really not enough.” Today, he has a job. He is employed by a German company that also pays for his private Slovak lessons.

First Attempt: Slovakia Wanted the Wife and Children to Come from Gaza to the Embassy in Tel Aviv

From the moment Ahmed discovered that he could not get his family out of Gaza through the Hala travel agency system, because they couldn’t afford it, he began doing everything he could in Slovakia to save them in another way. In the meantime, he received increasingly desperate messages from his wife.

“My children have lost a lot of weight. They don’t have enough food or drinking water. And my youngest son Yusuf has stopped talking. According to the doctors, it’s a result of shock. He was in kindergarten when a rocket hit a car on the other side of the park, which exploded and burned down with the people sitting inside. The explosion also killed one of the children who was in kindergarten with Yusuf. He doesn’t sleep at night at all, he just keeps shaking and crying. He is traumatized,” Ahmed says of the situation at home.

When we ask why kindergartens are still open in Gaza, Ahmed explains that parents are trying to maintain some semblance of normalcy for their children. They organize activities for them so they can be with their peers and not be so affected by the war.

Ahmed Ghorab has a legal right to his family to obtain Slovak visas to join him. These visas are issued in Slovakia under the Foreigners’ Residence Act, and Ahmed is entitled to a family visa as a person who has received subsidiary protection in Slovakia (subsidiary protection means that he has not yet received asylum, but cannot return to his country of origin due to the ongoing war there).

Despite this right, all of Ahmed’s efforts to evacuate his family from the war zone have been met with unfulfillable demands from the Slovak authorities. The first attempt to get his loved ones from the Gaza Strip to Slovakia was conditioned by the state institutions on the children appearing in person at the Slovak embassy in Tel Aviv and having their fingerprints taken there. But that was not possible. “Just getting close to the Gaza Strip’s border with Israel is prohibited, let alone going to Tel Aviv. They shoot Palestinians at the border without asking questions,” says Ahmed.

Lukáš Novák from the Slovak League of Human Rights, who is legally representing the Palestinian refugee and his family, adds: “Ahmed’s family has the legal right to be granted national visas based on Section 15(2) of Act No. 404/201 on the Residence of Foreigners. These visas are granted to family members of persons who have been granted asylum or subsidiary protection in Slovakia. The family has all the documents that need to be attached to the application. However, the problem is that visa applications can only be submitted at the relevant Slovak embassy abroad. For Palestinian citizens, this is the Slovak embassy in Tel Aviv, which they cannot visit for understandable reasons.”

Novák continues, “The Slovak authorities granted Ahmed’s family a territorial exemption, thanks to which they could also submit applications for national visas at the Slovak embassy in Cairo or Beirut. The problem, however, is that the family does not have a real possibility to travel to any of these countries, because as Palestinian citizens they need visas to enter these countries. However, it is almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain them in the current situation. We also requested an exemption from the obligation to appear in person at the embassy so that they could submit a visa application remotely. However, the state authorities refused.”

We wrote more about how difficult it is to travel from the Gaza Strip, and how high the unofficial fees are for such travel, here.

Ahmed Ghorab with his wife in Gaza, before the war. Today, Ahmed lives in Slovakia, while his family remains trapped in the Gaza Strip. Source: Ahmed Ghorab (private archive).

When Ahmed’s lawyer explained to the Slovak authorities that war was raging in the Gaza Strip and there was no way for residents there to get to Tel Aviv, they reportedly replied that those were the rules. After more than a year of efforts to reunite the family, the only result remains doubt as to whether the Slovak state even understands what is really happening in the Gaza Strip.

“None of the authorities are willing to take responsibility. There is a lack of political will,” says lawyer Lukáš Novák.

When asked by investigace.cz whether the Slovak Embassy in Tel Aviv actually required Ahmed Ghorab’s family to personally appear at the embassy and provide biometric data, such as fingerprints, the Communications Department of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic, which also speaks on behalf of Slovak embassies, responded:

“The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic pays special attention to vulnerable groups of persons, including family members of asylum seekers. In this case, the consular service has been actively coordinating its activities with other relevant state institutions for a long time – the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic, the Migration Office of the Slovak Republic, the Border and Foreign Police Office of the Police of the Slovak Republic – as well as with foreign partners through our diplomatic missions.”

“It should be emphasized that the Slovak Republic and its diplomatic missions act exclusively within the limits of the law,” concludes the response from the Communications Department of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic.

Second Attempt: Embassy Proposal to Send Passports by Mail

Eventually, the embassy recognized that it would probably not be easy to travel from Gaza to Tel Aviv during the war, so it came up with a backup plan. Ahmed’s family was supposed to send their passports to the embassy by mail. “I don’t know what they were thinking. There is no mail service in Gaza right now, of course. And even if one of my foreign colleagues brought them to the embassy, how would my family pick them up, anyway?” Ahmed asks.

Third Attempt: No Replacement Documents for Ahmed’s Family

Ahmed’s lawyer suggested to the Slovak embassy in Tel Aviv a solution that had already been successfully used by some other European countries in evacuating people from Gaza. Their embassies issued them so-called replacement travel documents, valid for only a few days. With these documents, people could leave the war zone and then apply for asylum.

“When we asked the Slovak embassy to do something similar for my family, they refused, saying that they cannot issue this type of document to people who do not have Slovak citizenship,” Ahmed says. “When we explained to them that this is standard practice in other European embassies, they refused to discuss it further. They said that rules are rules.” Ahmed is convinced that the Slovak embassy is actively preventing his family from leaving the Gaza Strip.

Fourth Aattempt: Just When Tthings Looked Promising, the Government Special Flight Did Not Arrive

Novák did not give up the fight to save and reunite Ahmed’s family. He first sent the application for a visa for the asylum seeker’s family to the Slovak Migration Office of the Ministry of the Interior and then to the Slovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both offices exchanged the application between themselves, neither, evidently, wanting to take responsibility.

Temporary documents, with which Ahmed’s relatives can enter Slovak territory, were finally issued to them by the Border and Foreign Police Office of the Police Presidium on the basis of a humanitarian exemption. The document was valid until October 22, 2025. The departure of a Slovak government special flight was scheduled for that day. The flight was granted permission to land at an airport near Gaza, from which Ahmed’s wife and children were to fly to Slovakia. Together with the Palestinian authorities and the Israeli government’s Office for the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), it was finally possible to secure all other necessary documents in time so that the family could travel on a government special flight.

But the joy was premature.

Ten days before departure, Ahmed and Novák discovered that the government plane had already been booked by someone else, meaning the family from the Gaza Strip would not be traveling again. The necessary coordination documents would have to be processed again.

When asked who from the Slovak government ordered the government special plane for this day, the Slovak government office replied that they do not have such information. According to data from the Flightradar aircraft monitoring device, one of the four planes of the Slovak government squadron with the code OM-BYA was in Brussels at the European Union summit. What happened to the other three planes is not clear. They have no record of the flight on Flightradar.

The exemption for entry into Slovakia has been extended by two months, until the end of 2025, but it is not at all certain whether the evacuation will be successful. “Every Palestinian citizen who tries to leave the Gaza Strip needs a permit from the Israeli COGAT office to travel. However, only states that have decided to accept these persons can apply for this permit,” Lukáš Novák says.

Slovakia has not yet requested this permit.

About the Gaza Project

Finding out what has been happening in the Gaza Strip over the past year has been nearly impossible. Foreign journalists are banned from entering, and local critics accuse them of being traumatized, biased, or paid by Hamas. Border crossings are closed to everyone except humanitarian aid and food trucks. That’s why we decided to do a series of interviews with people who lived in Gaza during the war and managed to leave, as well as with people who still live there.

For these 13 interviews, we prioritized authenticity over political views or religious ideologies. We consulted experts on their accounts, analyzed video footage shot in Gaza, and tried to verify them with UN reports, reports from humanitarian organizations, social media, and Israeli journalists.

We spoke to traders from the Gaza Strip who very specifically named the problems facing Gaza: extortion, corruption and the rise of organized crime.

We also spoke to women who survived the bombing. We spoke to a boy burned by white phosphorus, who has deep scars on his hand and shoulder. We spoke to little girls who want to become doctors because of what they saw in Gaza. We spoke to people who have lost their entire families, their homes, their parents, their future. But also to people who have not lost hope that life has meaning and are grateful to be alive.

During the project, we visited Gazan refugees in Cairo, Egypt, where it was 40 degrees Celsius (104°F). We conducted online interviews with emaciated journalists in Gaza, behind whom an air conditioner hung by a single wire from a cracked wall. In a smoky office, we spoke to traders who had built their businesses on importing food into the Gaza Strip, our conversations constantly interrupted by phone calls from their drivers directly from Gaza, pleading for help.

We are not attempting to explain in a few pages the entire history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one of the most historically complex conflicts in the world. Our goal is to bring the first-hand testimonies of a few people about life and death in Gaza.

Read other stories from the Gaza series that we have published so far:

The first episode, The Law of the Strong, shows how Gaza was taken over by organized crime groups during the chaos of the war. In the second episode, Marah Wants to Die, we hear the story of a young woman who lost part of her family and still cares for her sisters. The third episode, Sorry Ma’am, But You’re Dead, follows a television production woman who survived her own death. The fourth episode, A Scientist from Gaza in Slovakia: My Family is Dying and the Authorities Say These Are the Rules, tells the story of Ahmed Ghorab, a computer scientist who managed to escape from Gaza but has been fighting Slovak bureaucracy in vain for over a year to save his family trapped in the war.

Listen to other stories from the Gaza series that we have published so far:

You can also listen to the entire Gaza series on the podcast channel Odposlech, which can be found on all podcast platforms. Direction, sound and music by Miroslav Tóth. Czech version: Renata Klusáková, Daniela Čermáková, Petr Gojda.

The Czech version of this article was published on Investigace cz.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Czech journalist, Pavla Holcová is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism. She is an editor at OCCRP and a member of ICIJ. She was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2023). Pavla is the winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award and, with her colleagues Arpád Soltész and Eva Kubániová, the World Justice Project’s Anthony Lewis Prize Award. She is based in Prague.