Šarūnas Černiauskas (Siena)

Mariusz Sepioło (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: Mart Nigola / Delfi Estonia 2023-10-04

Šarūnas Černiauskas (Siena)

Mariusz Sepioło (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: Mart Nigola / Delfi Estonia 2023-10-04

International criminals used Estonia’s deficient cryptocurrency regulation to turn the small country into a hub of financial crime where over a billion euros have been laundered or defrauded from victims. Now the same actors are relocating to other countries who repeat all the same mistakes

- Over the last 5 years Estonia became a global hotspot for crypto companies: as of mid-2021, nearly 55% of all virtual currency service providers in the world were registered in Estonia.

- Estonia’s liberal crypto licensing system enabled such companies – often with non-resident owners and clients – to promote themselves as EU-licensed financial services.

- VSquare and partners analysed close to 300 crypto companies and discovered dozens of cases of massive fraud, money laundering, sanctions evasion and illicit financing of criminal enterprises and paramilitary organizations.

- VSquare and partners identified multiple cases where the anti-money laundering (AML) officers and managers of crypto companies were clearly inadequate and underprepared for the work and in dire financial situations: taxi drivers, a welder and a person living on social benefits were responsible for dozens of crypto firms.

- When the Estonian state began tightening the regulation and stripping companies of their licenses, many of them moved to new countries in Europe, such as Lithuania. This shows that fixing the system in one country doesn’t change much at all.

“Usually I was just a shell; I didn’t work with the transactions. I didn’t know what kind of millions went through there,” says Sergei Bezrodny, an unemployed plumber from the Estonian town of Tartu. His public LinkedIn profile claims he has almost 20 years of experience in finance and banking, but Bezrodny is surprised to learn about it and says it is a “mistake”.

And yet, Bezrodny is a former director of 24 international cryptocurrency firms.

“I don’t want to talk about it really. It was a while ago in the past and I had enough problems with that,” he says.

He now claims to be unemployed as his career in Estonia’s finance sector was cut short after banks started to close his accounts because of fear of money laundering.

“I had to open all my accounts in Lithuania,” the unemployed plumber explains.

“Now I just sit at home.”

The “virtual assets” licensing system established in 2017, which the Estonian state sold to the world as pioneering and innovative, metastasized into a Wild West of shadowy firms operating in the jurisdiction, resulting in massive amounts of illicit funds flowing through the European Union.

The term “licensed in the EU” became a selling point for international fraudsters who used the jurisdiction to inject trust in their illegal operations. As a result, during the last six years, 1644 licensed cryptocurrency companies have operated in Estonia: one for every 800 residents in the country.

Forty percent of those are related to just three company formation agencies in Estonia.Two of them provided “AML (anti-money laundering) compliance officers” to the companies. VSquare and its partners Delfi (Estonia), Siena (Lithuania), Fronstory.pl (Poland), Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel, ZDF (Germany) and Der Standard (Austria) have established that many of the “specialists” hired by these crypto firms had no background whatsoever in money laundering compliance and were people with financial difficulties seeking a quick paycheck.

We identified a taxi driver in deep debt, a welder banned from any business activities, a person living in subsidized housing, and an unemployed plumber, who collectively were responsible for more than 60 crypto companies as either an official director or AML officer.

Looking through hundreds of licensed companies, we found Russian intelligence ties, vast money laundering operations, dozens of cases of international fraud, and a serious lack of transparency: hired actors, fake profiles, and fraudulent owners of the companies.

Although over 1500 crypto companies have lost their licenses since the Estonian state started to fix its broken regulation, it didn’t mean that the operators stopped their activities. Many of them moved to other European jurisdictions like Lithuania, which now hosts over 800 virtual assets companies.

AML office in public housing

According to Estonian crypto license applications acquired and analyzed by our data reporters, eight crypto companies are related to a single address in Tallinn, Paagi st 10. This is a social accommodation building owned by the city government meant for underprivileged people who are not able to secure a place of residence for themselves and who need help to cope with everyday life. The address in question is the residence of a 65-year-old Estonian citizen, Igor Torsin.

Torsin complained about drunk and troublesome neighbors in his subsidized housing in 2017. By 2020 he was responsible for eight crypto companies’ AML compliance operating from the room pictured here. Source: Rauno Volmar / Delfi Estonia

For example, until June 2022 Torsin was the management board member and AML officer in BITEEU DCX OÜ, a company that still has a valid crypto service license in Estonia. Biteeu is a European branch of Kazakhstan’s exchange Intebix, co-founded in 2019 by Kazakh businessmen Talgat Dossanov and Shukhrat Ibragimov, the son of local oligarch Alijan Ibragimov.

FinTelegram, a website which regularly publishes investor warnings for cryptocurrency companies, names Steveyx, Venus Exchange Services and Paytechno as scam facilitators providing payment services to fraudulent operators. Torsin has been in charge of AML procedures in all of them.

Asking about investor warnings against his companies, Torsin says that he left Paytechno when Interpol started asking questions, but also insists that these matters are confidential. He denies being a nominee director and officer for hire but insists he is a real anti-money laundering specialist. “They told me that you need to study and I studied so much,” he says. When asked, who are “they”, he only says: “Those who invited me.”

Looking at other licenses of Estonian crypto companies, one can see a pattern. People with obvious financial difficulties and no experience in the field have been used as AML officers in dozens of international crypto companies. For example, a welding specialist, Kirill Saksen, has been bankrupt as a private person with a ban from practicing business since September 2021. Saksen is associated with 22 crypto companies, in five of them as an official AML expert. One of them, ReliabilityStabilityIncome OÜ, which operated a Russian exchange called RSI Capital, has been blacklisted by the Russian Central Bank since 2021 under suspicion of being a financial pyramid.

Saksen says he has since quit working in the field of cryptocurrency AML.

“I’d rather go and weld something,” the penniless welder-AML officer told us now. “I like to do more stuff by hand,” he explains, saying being a welder is more profitable than being in crypto.

Providing AML experts is a common service among the company formation agencies in Estonia who have been attracting international crypto-investors to Estonia en masse. About 668 crypto companies can be traced back to only three formation agencies. For example, Eesti Firma (translates as “Estonian Company”), a company associated with 266 crypto firms alone, is related to Igor Torsin’s companies. It lists “implementation and integration of effective payment and AML/KYC (know your client) solutions” as its official service on their webpage.

The company’s representative, Ilja Nikiforov, says that he has no reason to doubt Torsin’s competence.

“We are not going to share retrospective competence assessments of people’s activities, but we can say that their competence has been checked by the Estonian FIU and FIU has deemed them to be in compliance with the requirements arising from the law,” he explained.

Questions arise about how the AML services were implemented when Eesti Firma took on Garantex Europe OÜ as a client.

Donations to Russian mercenaries and funds from drugs

“They smelled great,” explains Russian mercenary Alexei Milchakov in an infamous interview to Czar.tv. Milchakov was describing how he deeply enjoys the smell of burning bodies of his enemies and loves to collect body parts from Ukrainians as trophies.

In his youth, he went viral for decapitating a puppy.

He is the founder and leading figure of the neo-nazi Rusich private military group, which has fought in Ukraine since the Russian invasion of the country’s Eastern region in 2014. Rusich – which was at the heart of the foundation of Wagner PMC – is one of the most infamous military groups who has fought for Russia in Ukraine.

Rusich Telegram channel applauded the video of the beheading of an Ukrainian prisoner of war (without taking responsibility for it), explaining: “You will be surprised how many of these videos will gradually pop up”.

Donating money to this kind of organization via the traditional banking system would be very difficult, because of the tight money laundering regulations and SWIFT sanctions against Russia, but Rusich’s numerous crypto wallets show how the military group has been able to amass hundreds of thousands of euros in donations via cryptocurrencies.

In April 2022, the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned the cryptocurrency company with offices in the Moscow Federation building but operated from the Estonian jurisdiction – Garantex Europe OÜ. Earlier, in November 2021, it had already sanctioned another Estonian company related to Chatex (Izibits OÜ, formerly managed by plumber Bezrodnoi), a Telegram-based crypto exchange which also operates from the same highrise in Moscow. Both exchanges are associated with huge criminal revenues.

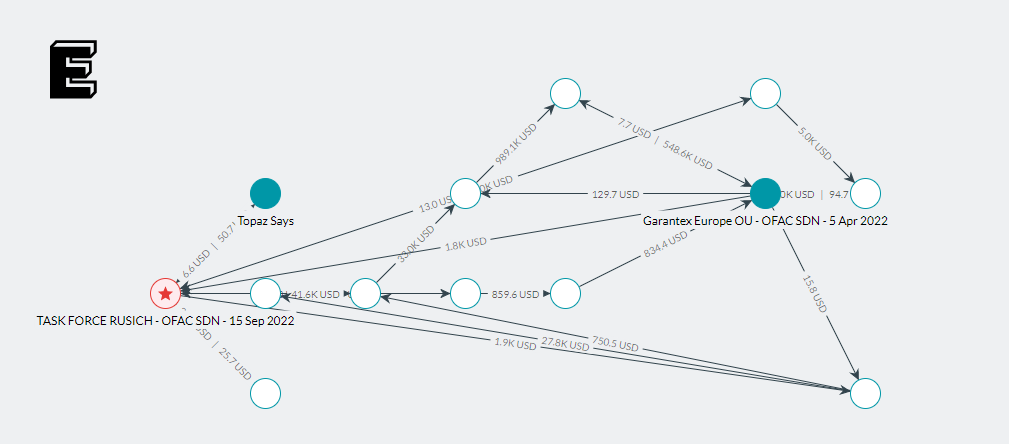

With the help of OCCRP’s Investigative Dashboard we looked into nine Rusich cryptocurrency wallets used in its fundraising campaigns. The Elliptic blockchain analysis tool indicates that the crypto wallets related to Rusich have raised around 200 000 EUR in total. For example, Elliptic indicates that about $8,697.26 has traveled from Garantex to Rusich and $5,122.92 from Rusich to Garantex. This means that whoever ran Rusich donation campaigns used (among others) Garantex to circumvent the sanctions regimes of Western countries and the banking sector.

A cluster of wallets transact between each other mixing the Rusich and Garantex Europe funds making it very difficult to track the source of these funds. This is an example on one of the eight Rusich wallets we analyzed.

The flow to Rusich wallets represents only a small part of the illicit funds funneled via the Garantex exchange. According to materials provided to us by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) citing the Global Ledger blockchain analysis tool, Garantex has exchanged huge revenues with Hydra – a now-defunct Russian darknet market dealing in illegal goods, drugs, documents and enabling money laundering services.

Hydra’s wallets received about 2,505 bitcoins originating from Garantex between April 2021 and April 2022, while it was operated from Estonia. In turn, 966 bitcoins originating from Hydra wallets reached Garantex Europe wallets. According to bitcoin’s value in that timeframe, that amounts to at least 138,6 million euros in revenue connected to a criminal marketplace selling drugs and offering money laundering services.

For example, Garantex also has a connection to a number of wallets transacting with the Lazarus Group, a North-Korean cyber criminal group, and with Ivan Vasilyevich Vakhromeyev (a.k.a. “Mushroom”), a wanted cybercriminal connected to Conti, a cybercriminal group with Russian intelligence ties. According to the US, Garantex’ illicit transactions with Conti amount to $6 million. Also in this network is Blacksprut, a Russian-language, drug-focused darknet marketplace which has won over many of Hydra’s former clients.

In December 2021, five months before Garantex got sanctioned in the US, its “offices” (actually a room provided by a law firm) in Tallinn were raided by the Estonian FIU. The FIU determined from their findings that in 90% of the cases, Garantex had not checked the identities of their clients at all. The company did not present suspicious activity reports to the FIU.

The FIU stripped Garantex Europe’s license on February 24 2022 (the day when Russia started the full-fledged war against Ukraine) but that didn’t stop the company from continuing business. VSquare partner Delfi found out that as a result, Estonia’s state prosecutors’ office started a criminal investigation into Garantex Europe and its management board in Estonia on the basis of unauthorized economic activities. According to the sources of Russian investigative journalists from Dossier Center, Garantex has been active during the war in Ukraine, enabling people to convert cash into cryptocurrency and move it abroad during the sanctions regimes, and its ownership also has ties to people associated with Russian intelligence agencies.

The anonymous ruble problem

On June 26, Bloomberg reported how the short-lived uprising of Yevgeny Prigozhin and his private army Wagner PMC in Russia generated significant traffic in the cryptocurrency market, suggesting that blockchain has become an important channel for moving Russian assets.

Another Estonian-related crypto exchange called Coinsbit is among the contributors to this phenomenon, enabling users to convert their Russian rubles into bitcoin.

“There are no restrictions for Russian citizens on our exchange,” a representative of Coinsbit explained in February 2023 and October 2022 in the official Telegram chat of the company.

We can find a reference to the Estonian company ITEcosystem OÜ on the company’s website, which actually lost its crypto license already in July 2020. Coinsbit was co-founded by Ukrainian IT businessman Nikolai Udyansky. However, he has claimed he sold his stake in Coinsbit in 2019, and the current owner is unknown.

Officially, ITEcosystem was founded and owned by a Ukrainian national named Yaroslav Yarovenko, according to the Estonian business register. Managing an international company with a huge turnover has been a great success story for Yarovenko, who was convicted in 2014 of stealing women’s shoes from the Kyiv Zara clothing store.

The Ukrainian former small-time thief, who operated an international crypto company, has no public connection with the business. At the same time, cryptocurrency worth billions of dollars is being transacted via Coinsbit monthly. There is no public profile or contacts on Yarovenko anywhere to be found so VSquare was unable to track him down. Coinsbit did not respond to VSquare’s questions sent via email.

There are also hundreds of warnings about scams associated with Coinsbit’s services on the internet. According to Trustpilot, its trustscore is 2.2 out of 5 from 212 reviews.

Although the website still has a reference to the Estonian company, which was its main operator at least a few years ago, Coinsbit’s official operating company has now been moved to the Seychelles which doesn’t get us any closer to understanding who is the owner of this multi-billion enterprise.

The creation of broken law

For decades, Estonia has built its international reputation through its ‘e-Estonia’ brand: a small country with a booming information technology sector that has also been the frontrunner in several initiatives, such as e-governance and e-residency. Another success story contributing to that narrative was becoming the first country in the EU in 2017 to establish a ‘licensing’ system for cryptocurrency companies.

However, the regulation went horribly wrong.

“This is a prime example of bad legislation. It could never have worked ,” explains a former government official who was involved in the creation of the virtual assets licensing law and who only agreed to talk to us off the record.

The law was adopted, and by the end of 2017, only four companies had the virtual assets license in the country. However, everything changed rapidly the following year when company formation agencies turned Estonian cryptolicensing into a business model and began to attract non-residents en masse.

Send us a hint

Have you been a victim of crypto fraud or do you have any other information that could help us investigate this issue further? We would be happy if you could help us and share any relevant information with us. We guarantee you confidentiality, but when you contact us, please also leave your contact details. This will enable us to ask you any further questions. Please contact us at [email protected] or [email protected].

A company formation agency called E-Advisors has provided services to 69 Estonian crypto companies. Its owner, Estonian lawyer Richard Witismann, describes how the licensing system became a profitable business. “Apparently, the country did not really understand what this would entail. But for us, this was an opportunity,” he explains. “The world was full of entrepreneurs who needed to say that their activities were licensed for marketing. Our clients wanted an opportunity to say that a country had taken a position on the legitimacy of their business.”

Asking if his company had clients who planned to defraud their clients from the start, Witismann says: “It’s very hard for me to say we didn’t, we probably did.”

The FIU soon realized that, according to the law, they had very few options for denying licenses to anyone who wanted them. Consequently, when they denied an application and the requesting company appealed in court, the FIU repeatedly lost the disputes.

“In spring 2018, I received a call from the FIU. They informed me that the situation was dire: whenever they didn’t issue the licenses, they were sued,” the official explains. “I told them they should ask for more resources and not hand out licenses to everyone!”

As the situation worsened, the FIU started receiving more and more complaints about fraud from international partners, but their hands were tied.

Cryptocurrency companies started to use Estonian licensing to inject trust into their activities. Although the license number cited in here is genuine, the “certificate” originating from a Chinese company formation agency website is completely made up and a hammer and sickle symbol has been added for unknown reasons.

“At some point, Estonians realized that they had no control over it. Most of these companies were shell companies that had nothing to do with the local economy. They did not [pay] taxes, did not employ [anyone], and exposed the country to a loss of reputation”, adds Polish lawyer Artur Kuczmowski, who specializes in registering companies in Estonia.

According to the Estonian financial intelligence unit (FIU), as of mid-2021, nearly 55% of all virtual currency service providers in the world were registered in Estonia.

From then on, Estonia initiated a massive reform to clean up the system. As most of the companies did not agree (or were not able) to follow new regulations, only 78 licensed crypto companies now remain out of 1644 at the time of writing.

The head of Estonia’s FIU, Matis Mäeker, confirms that the US sanctions decisions show how these kinds of companies helped finance Russian mercenary groups and even North Korean nuclear programs.

“But there’s nothing that links them with Estonia, only that the service providers have created their address, provided some random nominal directors and AML contact [people] found in the street who understand nothing. They don’t even know which companies they are directors of,” Mäeker says.

“When they are laundering money, our hands are tied. In a criminal sense or in a sense of supervision, they are not even here. They are here only on paper.”

Sanction evasion via P2P

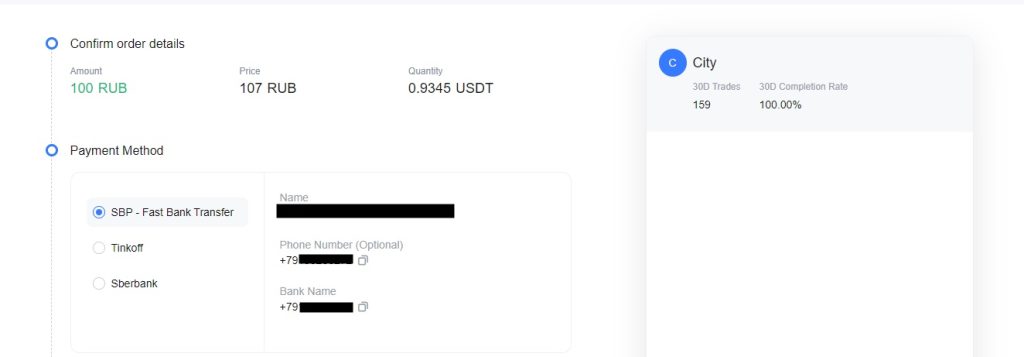

Crypto exchanges implement the so-called person to person (p2p) method to bypass Russian sanctions.

For example, international crypto exchange MEXC at the time of writing has a daily trade revenue of around 500 million euros and it owns a branch in Estonia (Mexc Estonia OÜ) with an active virtual assets license in the country.

MEXC also offers ruble payments via P2P method: you wire money to a private Russian bank account and receive cryptocurrency to your MEXC wallet. MEXC doesn’t allow withdrawing funds directly but there are no restrictions to transfer the cryptocurrency to exchanges which support withdrawing USD and EUR using the European and US banking system.

MEXC enables Russians to deposit rubles into the exchange via a private person’s bank account.

The press secretary of the Estonian FIU, Õnne Mets, says that this activity from MEXC is known to the state agency and it is currently reviewing the company’s license. “This procedure has lasted for more than a year and will receive a solution when all the relevant facts have been clarified,” Mets says.

The manager of MEXC Estonia OÜ Ljudmila Budnikova confirms that the company is waiting for Estonian FIU to extend its’ license. She claims that the European branch in Estonia is a completely different company from MEXC Global.

“Simply put, MEXC Estonia OÜ is a unit operating as a franchise to serve European customers. This means that the company can use the global brand name “MEXC” but has no corporate connection with the brand owner,” she claims.

Actors and fake profiles

The fact that officials’ hands were tied is no surprise to Nico S. (full name known to the editorial board) from the Netherlands. In January 2022, he had made several statements to the Estonian police because “an Estonian” crypto company called Arbismart had not returned his funds. No criminal proceedings were opened. He was told that the owner of Arbismart was not Estonian and not based in the country. The company had no actual premises there.

But the public had been persuaded of the opposite. The company advertised that it was “fully EU licensed and regulated” and “regulated by the Financial Intelligence Unit (“FIU”) in Estonia”. To boost credibility, Arbismart had published “articles” in numerous crypto blogs. The articles featured Mike Meyers, CEO; Andrus Steiner, CTO; and Dennis Müller, Head of Business Development. According to their public LinkedIn pages, Meyers claims to be from a small village of Risti in Estonia, Steiner from the small town of Rakvere, and Müller is described on a blog as an IT graduate from Tallinn University, except… none of these people actually exist and Steiner even used images of other person found from the internet to give an illusion of presence in Estonia.

A series of videos uploaded to YouTube showed alleged Arbismart employees standing in an office and praising the service. In fact, these were actors. These videos were shot in 2019 in Moscow, at the design centre ARTPlay, according to one of the participants of the shoot interviewed by VSquare. In the studio, the whole operation was run by two Arbismart representatives in their 30s. One of them, known as Eli, spoke Russian with the actors but Hebrew with his business partner. They paid the actors in cash.

VSquare could not discover the true beneficiary of this operation. In the eyes of the Estonian state, Arbismart was owned by a 34-year-old Ukrainian, Dmytro Averianov. Averianov is in debt for utility bills and owes child support. At an alimony hearing, Averianov’s ex-wife described how the man is unemployed in the winter, but in the summer he gets occasional jobs to help put roofs and facades on apartment buildings.

To become an investor, one had to buy so-called RBIS tokens created by the company, which it promised to buy back in 2022 at a higher value. Nico invested one bitcoin in 2019, worth €6,000 at the time. “By December 2021, the theoretical value of my assets in RBIS tokens plus arbitrage gains was around €95,000,” he explains. Soon enough, however, investors began to understand that there was no promised buyback programme.

Finally, Arbismart paid Nico back €6,000 in January 2022. However, Arbismart kept his bitcoin – the coin was worth €40,000 by then. Others were not so lucky. Telegram victims’ chats indicate that numerous clients have still received nothing and the amounts lost range up to €50,000.

In February 2022, Arbismart wrote on Telegram that the Estonian FIU had introduced “draconian new regulations” in Estonia and Arbismart planned to move to Lithuania, where “the regulator body brings greater experience” and “offers a more welcoming environment for Fintech companies’.

In September 2021, Arbismart UAB was founded in Vilnius (initially under a different name, changed to Arbismart in November 2021).

Migration to Lithuania: a full start over

After moving its operations from Estonia to Lithuania, Arbismart continues to state it is a “secure, EU authorized, interest-generating wallet and exchange”.

After moving to Lithuania, Arbismart indicated another Ukrainian owner: Pavlo Havrylov, with an address in Nova Kakhovka, a frontline city in Ukraine.

Arbismart claims it has an “active operating authorization issued by the Lithuanian FCIS” – the Financial Crime Investigation Service. The FCIS doesn’t issue licenses or any other kind of “authorization” to crypto exchanges, the deputy chief of FCIS Audrius Valeika told VSquare.

This isn’t the only part of Arbismart’s official statements that isn’t exactly true. The company claims it is required to provide “adequate operational capital”. In fact Lithuania and Estonia have tried to tackle the crypto companies by demanding a minimum share capital from the operators. In Lithuania it has to be at least 125,000 euros in share capital. Arbismart’s share capital is 2,500 euros.

Arbismart’s official premises in Lithuania are limited to 12 square meters in this Soviet-era industrial complex. Source: Andrius Švitra / Siena

In an attempt to reach Arbismart for comment, VSquare called the two numbers indicated by the company in the Lithuanian registry. One was answered by a recording. The other number apparently belonged to a formation agent that helped Arbismart set up their Lithuanian business. He confirmed that Lithuanian law enforcement also called him in an attempt to reach Arbismart, and agreed to share the number for the person he considered to be Pavlo Havrylov. However, that number was offline.

VSquare managed to find Pavlo Havrylov. The 34-year-old Ukrainian confirmed it was his personal details indicated in the Lithuanian company’s documents, but claimed to have no knowledge of Arbismart or any connection to the company in general.

“What? Who am I? This is the first time I heard of it”, Havrylov said in a phone interview.

He said this was not the first time his identity got stolen. “I never took part in any of it. Once I got questioned [by authorities], they asked how do I have these companies where I’m allegedly the director. I have no knowledge of this”, he explained.

When asked if he would testify to Lithuanian authorities if they investigated Arbismart, Havrylov said this is not his main concern now, since he has enlisted in the Ukrainian army.

Arbismart did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Migration to Lithuania: a familiar story

Arbismart is just one example of many showing how crypto companies have been able to continue their business activities even after being expelled from Estonia due to tougher regulations implemented in 2022. VSquare has established that at least 68 crypto companies in Lithuania have clear connections to cryptocurrency firms operated in Estonia using the same brand, company name or internet domain. 39 Lithuanian crypto companies have connections to Estonian service providers and company formation agencies.

For example, the Estonian law firm Gofaizen & Sherle is connected to 11 crypto companies in Lithuania. Gofaizen & Sherle also advertise jobs for AML/MLRO (anti-money laundering/money laundering reporting) officers, claiming “the job requires minimal involvement from 1 to 20 hours per month” and is “perfect as a side job or additional income source”. The job ad presents no qualification requirements and suggests it as an opportunity for university students to make some extra cash. The head of Lithuania’s Center of Excellence in Anti-Money Laundering, Eglė Lukošienė, claims this does not look like a description of a real MLRO position.

“It is a full time job. If transactions are happening, they have to be monitored”, Lukošienė told VSquare.

Siena’s intern, a student at the Vilnius university, responded to Gofaizen & Sherle’s job ad. Posing as a potential candidate, she called the company and asked if the job requires any experience in the field. The answer was: “No”.

VSquare emailed Gofaizen & Sherle with a request to comment on the quality of the AML/MLRO officers they hire for their clients in Lithuania. The company did not respond to the e-mail, all attempts to reach Gofaizen & Sherle by their Estonian and Lithuanian phone numbers were fruitless

A Lithuanian company called CAML claims to provide MLROs to 20% of the Lithuanian crypto industry. In July, CAML had more than 20 employees with an average salary of less than 800 euros before tax, which is below the Lithuanian minimum wage. The average salary in the company is significantly fluctuating, but rarely makes it above 1,000 euros before tax.

In Lukošienė’s view, these figures look nothing like the actual money made by real AML officers. “Less experienced specialists earn up to 2,600 euros before tax. Those with more experience earn above the 2,600 mark”, she claims.

Audrius Valeika, the deputy director of Lithuania’s FCIS, admits that MLROs and AML competency is being faked, similar to what had happened in Estonia.

Another journalism student from Lithuania also called CAML to be considered for the AML/MLRO position. The company’s representative confirmed there are virtually no requirements for the position and asked for a CV. He said that hourly wage is between 10 and 20 euros. Later, the candidate got rejected, on the grounds that the only currently open position does require some experience.

Povilas Norkūnas, the director of CAML, was also approached for comments by phone. He did not argue that his company’s AML/MLRO officers are paid below minimum wage, on average.

“So what?” he said.

When asked about the AML/MRLO officers’ qualification for the job and the fact that the company is offering the job to university students, Norkūnas refused to respond to any further questions and asked them to be sent via email.

The request for comments was sent late last week. In a written response, Norkūnas claimed his company values “honesty, quality and value” and all of their employees have at least two years of experience in the field. CAML’s director did not directly respond to the question about hiring university students for AML/MLRO position.

“We are not in control of our employees’ spare time or the decisions they take regarding their future, career or additional studies”, he said.

Migration to Lithuania: sanction evasion

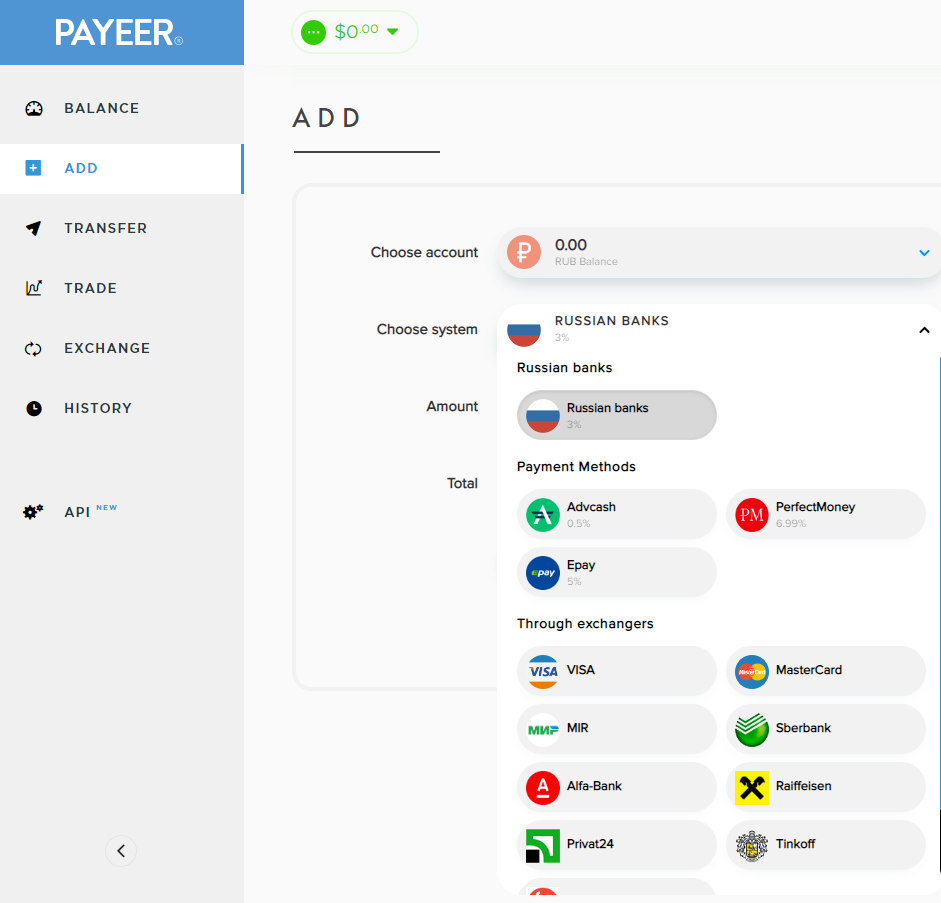

In March 2022, a YouTube user uploaded a tutorial in Russian titled “Bypassing Sanctions Without VPN.” In the video, the uploader instructs Russians on how to evade payment sanctions via Payeer, a popular crypto exchange and payment processor in Russia. Numerous similar tutorials can be found in Russian forums and websites. At that time, Payeer was operated from Estonia (Payeer OÜ) and it boasts to have millions of customers, many of them based in Russia.

In Payeer, funds can be deposited via Russian banks and withdrawn in USD via Advcash and Perfectmoney.

Since its establishment in 2012, Payeer has operated through various jurisdictions. By 2023, it had lost its license in Estonia and reestablished itself in Lithuania as Payeer UAB registering a company involved in crypto exchange activities there. The actual beneficiary of the enterprise has never been clear as with each incarnation the ownership information of the operator has been different. In Russia, its first incarnation, Payeer RUS LLC, was founded by a woman named Evgenia Kosolapova, who doesn’t appear to have any public profile in connection to payment and crypto services.

During its operations in Georgia, Payeer was officially owned by a Ukrainian, Kostiantyn Buriachenko. The same Buriachenko established BlackShire United LP’s Czech spinoff company, which was owned by Dexberg Inc and Montbridge Inc from the Marshall Islands, notorious for concealing the true beneficiaries of suspicious companies. Journalists from Mother Jones have linked the Scottish company Blackshire to a network of Russian-backed shell companies associated with suspicious political donations to Albania.

During Payeer’s operations in Estonia, a Russian national named Liubov Svezhentseva was listed as the UBO (Ultimate Beneficial Owner) of Payeer. However, she is officially the marketing director of Payeer, and VSquare was not able to confirm her position as a founder/owner. According to Payeer’s homepage, the service provider also claims to have a financial license from Vanuatu.

In Lithuania, Payeer now declares another Russian national as beneficiary – Ekaterina Olegovna Gorshkova, with an address in the Netherlands.

A mirage of funds

VSquare found several cases in which crypto companies use cryptocurrency to claim that they fulfill the minimum share capital requirement (125,000 EUR) in Lithuania. This method may be used as a way to bypass tougher regulations implemented in the hopes of cleaning up the market. For example, in January 2023 Payeer uploaded an official asset valuation report made by a hired expert in Lithuania, claiming the amount of cryptocurrency owned by Ekaterina Olegovna Gorshkova was worth exactly the amount in euros needed for Payeer to reach the minimum capital required in Lithuania.

The document indicated a particular crypto walled with its unique ID. Several publicly available wallet analysis tools indicate that 125,000 EUR worth of crypto currency (USDC) was sent out from the wallet on 17th of January 2023 so the wallet doesn’t actually have the necessary assets to fulfill the requirement.

Lukošiene from Center of Excellence in Anti-Money Laundering concludes that crypto is not a reliable asset in terms of share capital.

“The practice you mentioned does not ensure the [reason] share capital is needed, in the first place: to provide security to clients, users and the company itself. So it seems like it doesn’t serve its purpose”, Lukošienė told VSquare.

Similarly to Arbismart, the phone number submitted to the Lithuanian registry by Payeer was offline. The Lithuanian formation agent who provided Payeer with company registration and his own address claimed to have no contact with the client. He also said the company is obliged to move from the premises within 12 months.

Payeer’s official address in Vilnius. Source: Andrius Švitra / Siena

Payeer did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Connection to Sberbank leadership

Similar to Payeer, another international crypto-firm, MoneySwap OÜ, operating the virtual assets platform Mercuryo, set up a new business entity in Lithuania, MoneyAmber UAB.

The Estonian FIU (Financial Intelligence Unit) refused to extend MoneyAmber’s license due to a lack of transparency in the ownership structure and incriminating information on the internet about the service provider. FIU noted that the investor warning website FinTelegram had noted that Mercuryo had brokered numerous crypto scams and was popular among Russian clients.

The shares of both the Estonian and Lithuanian business entities of Mercuryo are managed through the Cypriot company MRCR Holdings. One of the shareholders of this Cypriot company is Akshin Dzhangirov. In cooperation with Siena, the Lithuanian Center for Investigative Journalism, we found out that Dzhangirov is the brother of Dzhangir Dzhangirov, the group CRO of Sberbank, one of the most important Russian state banks.

Akshin Dzhangirov is a direct shareholder of MRCR Holdings since October 2020. He is the third largest shareholder of the company, after Moneybag, an offshore entity based in the Cayman Islands, and Target Global, registered in Delaware, US.

However, data on Dzhangirov being one of the Lithuanian company’s beneficiaries was never provided to the state registry. MoneyAmber, the Lithuanian company controlled by MRCR Holdings, lists only one beneficiary – and it’s Petr Kozyakov, a Russian national reportedly residing in the UK.

In written comments to our Lithuanian partner organization Siena, Mercuryo’s Senior Legal Counsel Adam Berker first stated it would be inaccurate to say they moved their activities to Lithuania, since “the entity in Lithuania was established 1.5 years ago with the aim of expanding [the] company’s presence in Europe”.

Regarding Akshin Dzhangirov, Berker stated he was “an early investor in Mercuryo and the third largest investor behind the founders of Mercuryo and Target Global”. “He is considered a minority shareholder (<25%) who does not exercise control over Mercuryo and is not operationally involved in Mercuryo’s business activities,” Berker added.

Mercuryo’s representative claimed the company was “not in the position to comment on the family relationship(s)” of their investors.

He further claimed Mercuryo has no business relations with Sberbank and has an unequivocal “stance against the ongoing war in Ukraine”.

Kyiv Independent and OCCRP’s Investigative Dashboard contributed to this story

Initially, this article contained an information about Akshin Dzhangirov receiving about 285,600 euros in income from Sberbank in 2021. This information has now been deleted due to the new evidence indicating against it.

“Tales from the Crypto” is a series of articles in which we investigated how Estonia became a global crypto centre involving the businesses of fraudsters, criminals and money launderers under the cover of hundreds of foreign entrepreneurs. Our partners in this project are Delfi (Estonia), Siena.lt (Lithuania), Frontstory.pl (Poland), Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel and ZDF (Germany), and Der Standard (Austria). The series was produced with funding from IJ4EU.

“Tales from the Crypto” is a series of articles in which we investigated how Estonia became a global crypto centre involving the businesses of fraudsters, criminals and money launderers under the cover of hundreds of foreign entrepreneurs. Our partners in this project are Delfi (Estonia), Siena.lt (Lithuania), Frontstory.pl (Poland), Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel and ZDF (Germany), and Der Standard (Austria). The series was produced with funding from IJ4EU.

Head of the investigative desk at Delfi Estonia, Holger Roonemaa has extensively investigated topics related to national security, including Russia’s espionage, interference, and influence operations in Estonia and the wider region. He is a member of the International Consortium on Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). Estonia’s national media association named him the journalist of the year in 2020 and 2021.