Who is behind the largest cyber-espionage operation in Poland? So far, it seems as if the Belarusian regime has benefited the most from the Polish hack-and-leak scandal. But there is evidence that the leak is an offshoot of the Ghostwriter campaign, an influence operation pursuing Russian interests. Our analysis has revealed that the activities of a group that might have compromised over 700 email accounts – including Michał Dworczyk’s private email – bear striking resemblance to the attacks carried out by GRU-linked hacker groups such as Fancy Bear.

Until recently, nearly every day for two months unknown perpetrators published new documents and screenshots of emails stolen from the inbox of the chief of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister of Poland, Michał Dworczyk, on a Telegram channel. The shared correspondence included messages about state and political matters sent between Dworczyk and the Polish prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, from their private accounts. The true scale and duration of the operation remain unknown; its origins might date back to the beginning of the pandemic.

The Polish-language Telegram channel, which had been publishing leaked documents – along with witty comments and memes – since early June was restricted for Polish audiences by the app developer in mid-July and soon after went completely silent. Before being effectively shut down, the channel had almost 90,000 views per day. The leaked documents are still available online: they have recently reemerged on Yandex chat and dedicated websites only accessible over Tor, but the scandal seems to have lost momentum in Poland.

However, few Poles are aware of another information stream: a Russian-speaking Telegram channel, where leaked documents about the Polish military first appeared in early February. The channel remains active and intact despite the Polish government’s efforts to shut it down. In Belarus, it has become a source of material for the regime’s propaganda machine.

Since early July, pro-Lukashenko media and commentators have been making effective use of this correspondence to validate their official propaganda narrative: that the massive 2020 protests in Belarus were inspired and sponsored by Poland. Moreover, both the Polish government’s reaction to the leaks and the opposition’s criticism of the situation fueled a statement on the Telegram channel supporting the idea that “the Polish regime censors social media to remove inconvenient information about its blatant interference in Belarus’s internal affairs,” which was reposted on the social media pages of Belarusian mainstream media outlets and channels such as OMON Moscow (this repost was quickly deleted).

Key findings

In recent weeks, we have cross-checked over 200 domains related to the infrastructure used in credential harvesting campaigns; analyzed the narratives disseminated on Polish and Belarusian social media; and interviewed sources from the Polish government, secret services, military, and cybersecurity companies to understand the backstage of the so-called Polish email scandal.

Here are some of our conclusions:

- The hack-and-leak scandal involving Dworczyk’s email account is related to an influence operation serving Russian interests that has been dubbed “Ghostwriter” by researchers from Mandiant, a cybersecurity company.

- There are important similarities between the activities of UNC1151, the cyber-espionage group that harvested credentials for the Ghostwriter campaign, and the activities of GRU-linked groups like Fancy Bear and Sandworm.

- The credentials and data stolen by UNC1151 might be used in several distinct disinformation operations or might be shared by cooperating groups engaged in different disinformation activities.

- Since spring 2020 a series of phishing attacks have targeted Polish politicians and other public figures, Poland’s Ministry of Defence remote work infrastructure and military targets in Ukraine.

- At the end of March, we published an investigation on an extensive disinformation campaign that used accounts compromised in phishing attacks to validate and disseminate fake news aimed at undermining Polish-Lithuanian relations and Poland’s position in NATO – and hence government and security agencies had many opportunities to take action, but did nothing until recently. Even though one of Dworczyk’s associates notified the Internal Security Agency (ABW) and other bodies responsible for cybersecurity about their private e-mail correspondence being published via a compromised Twitter profile in April, the possibility that Dworczyk’s email account had been hacked was not investigated until June.

The government deepens the chaos

On July 12, after almost six weeks of silence from the parties involved, which only deepened the chaos and disinformation surrounding the leak operation in Poland, Dworczyk and the Chancellery of the PM provided some details about what happened. For now, it has been officially confirmed that the private email address of the chief of the Chancellery of the PM has been the target of at least five phishing attacks, two of which, those launched in September 2020 and May 2021, were successful.

The government has declined to give an official comment on the authenticity of the published messages, citing the ongoing investigation. But its silence on the matter is meant to distract from the sensitive content of the emails and the fact that they were sent from the private accounts of the head of the Chancellery of the PM, government officials, the prime minister, and some of his informal aides working for state companies.

Chief of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister of Poland Michał Dworczyk. Warszawa, March 03, 2020.

Source: Krystian Maj/KPRM

Unofficial sources close to the Chancellery of the PM have identified most of the emails and documents published on the Polish-language Telegram channel as original pieces of correspondence from Dworczyk’s private account. That might, however, change at any moment. In the case of the hack-and-leak attack on Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016, doctored emails were identified only a year later. “Tainted leaks plant fakes in a forest of facts in an attempt to make them credible by association with genuine, stolen documents,” noted at the time John Scott-Railton of Citizen Lab, which analyzes disinformation operations. “It allows you to subtly shape a narrative that an organisation may have difficulty directly confronting.”

Several documents published on the Telegram channel aimed at Russian-speaking audiences were manipulated to seem more official than they were. Fabricated comments attributed to Polish politicians were even used to validate and promote some of these documents. These falsified endorsements were posted on the alleged “authors’” compromised Twitter accounts — a strategy known from the previous attacks attributed to the Ghostwriter operation.

Those behind the operation could have easily foreseen that given the current polarization of the public debate in Poland, the email scandal would soon take on a life of its own. For instance, a statement that “most emails and documents are genuine” would power the narrative of opposition politicians. A contrasting statement, that some of the documents may have been manipulated, supports the narrative of Poland’s ruling party (PiS), as it is trying to divert attention from the controversial content of some of the leaked emails.

Stirring up chaos, increasing polarization, and riling up the public are typical goals of organized disinformation operations.

The operation targets Poland, Lithuania, and Germany

In late March, we published the results of an investigation conducted by Reporters Foundation and VSquare. We were first to link the months-long campaign led by unknown hackers who hijacked several Polish politicians’ social media accounts and posted compromising and inflammatory content with the Russian-linked disinformation operation targeting NATO members. The operation, dubbed “Ghostwriter,” was described in the summer of 2020 by Mandiant, a cybersecurity company. In May 2020, researchers from the Stanford Internet Observatory also independently analyzed some of its facets.

Experts believe that from March 2017 onward an unidentified group was running a European disinformation campaign aligned with the Kremlin’s security interests. The operation was dubbed “Ghostwriter” due to the pattern repeated in most attacks – the perpetrators hack into news portals using stolen login credentials, publish fake news articles by non-existent authors (i.e., “ghostwriters”), and spread them through forged institutional emails. This group carried out an attack on the website of the Polish War Studies Academy in April 2020, publishing a fake letter from the head of the academy that encouraged resistance to cooperating with NATO. The outcomes of such hacks were then disseminated by fake social media accounts.

In March 2021, we reported that the authors of the Ghostwriter operation had expanded their modus operandi – the attackers began to spread fake news not only through the accounts of fictitious persona but also through the hacked accounts of real-life public figures, a strategy observed in Poland since November 2020. We also managed to tie these incidents to a phishing campaign that has been targeting the private email accounts of Polish officials since mid-2020.

We found that

- attackers may have already obtained a huge amount of sensitive information from the email accounts of key people in Poland;

- the phishing attacks targeted thousands of email accounts (current numbers indicate over 4,000 phishing attempts with over 700 email accounts likely compromised);

- phishing targets were deliberately chosen: the list of possible victims includes family members of politicians, analysts, journalists, scientists, and soldiers (the potential targets of recruitment attempts by foreign intelligence);

- hijacked social media accounts were used to create and spread disinformation as part of campaigns that also involved the use of compromised websites of public institutions and local news outlets; and

- the 2020 attacks were primarily aimed at harming Polish-Lithuanian relations and Poland’s NATO membership. However, Belarus was already mentioned in the attack in September 2020 – one of the fake fake articles argued that Poland and Lithuania wanted NATO troops to be sent to Belarus.

In April 2021, after a similar series of phishing attacks on MPs from the German Bundestag, Mandiant issued an update on the Ghostwriter operation. This report, consistent with our findings, includes new technical details about the influence campaign. The company’s analysts have linked the Ghostwriter operation to the UNC1151 cyber-espionage group, which is likely a state-sponsored actor that carries out phishing and malware attacks.

How Ghostwriter works

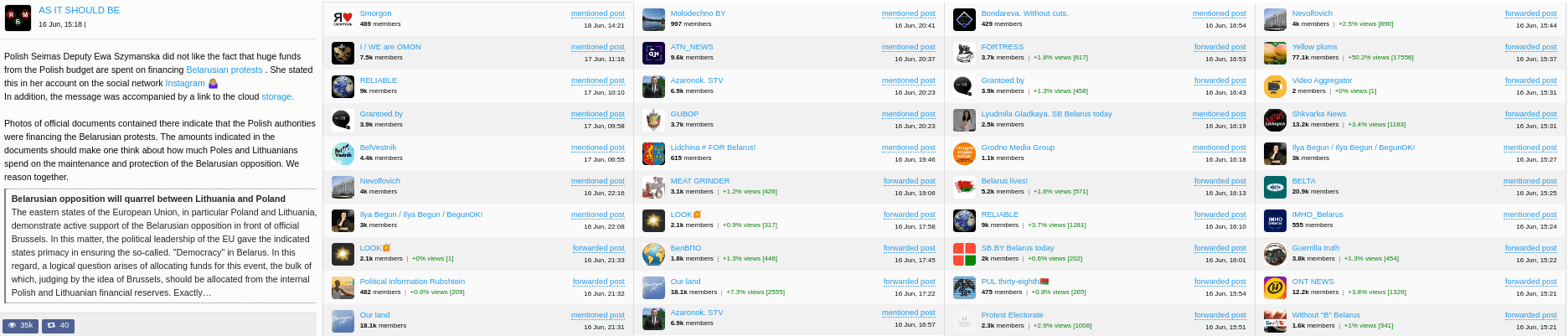

Let’s now have a closer look at two disinformation attacks linked to the Dworczyk leaks. Both attacks involve coordinated publications of fabricated content on hacked social media accounts of PiS’s associates, the pattern typical for Ghostwriter operation. The hacks also include some new elements. In both cases, the screens of such fabricated posts were used by the Telegram channel or by the entire Belarusian propaganda machine to spread false narratives:

- that there is widespread criticism of Poland’s support for the Belarusian opposition, even within the ruling party,

- that the protests against the results of the presidential election had been inspired and funded by Poland.

The first attack from this series is conducted at the end of April and includes a leaked document that was previously published by a Belarusian blogger (see details in the graphic presentation below, click on the button in the top left corner to see interactive elements).

Towards the end of April 2021, when Agnieszka Kamińska’s (the Head of Polish state radio) hacked Twitter account and the Telegram channel were used in an attack, there was also an attack in Lithuania that targeted Belarusian opposition activists Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Paweł Latuszka. It also used some new elements – a fake request for grants. The attackers used the account number of a Polish charity organisation from Vilnius, as well as a fake YouTube video created two days earlier, and the hijacked accounts of a member of the Lithuanian Freedom Fighters Union, which were used to disseminate a link to the fake post on Facebook and Twitter. Such a fabricated narrative was meant to present Lukashenka’s opponents as frauds and embezzlers. The attack was described by experts at DFR Lab, who linked it to the Ghostwriter operation.

After the document was published by the hijacked account of Agnieszka Kaminska, Dworczyk’s associate reported it to the cyber threats response teams at Internal Security Agency (ABW), Ministry of Defence (MON) and NASK. However, it never occurred to anyone that the hack could have originated in Dworczyk’s email account. By June, all seems to be forgotten.

The same-pattern disinformation attack takes place on June 17, when the Dworczyk leaks scandal is already widely disputed in Poland.

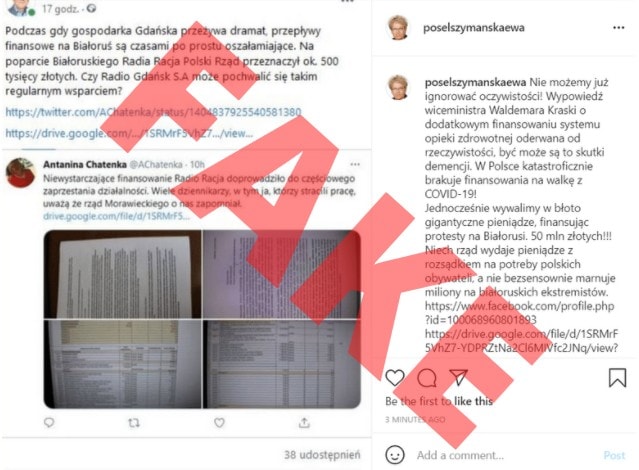

This time, the source material is a document with a grant proposal coming from the hacked email of Rafał Dzięciołowski, the president of the Polish Solidarity International Foundation, which supports projects in the Eastern Partnership countries. The disinformation attack also uses hacked social media accounts of PiS MP Ewa Szymańska, where screenshots of a fake discussion about the documents stolen from Dzięciołowski’s email account appeared.

The discussion included fake elements posted on other hacked accounts and revolved around the budget of Radio Racja, which broadcasts to the Belarusian minority in Poland and is supported by the Solidarity Foundation.

Dzięciołowski’s and Szymańska’s private email addresses were in Dworczyk’s hacked email account – a fact confirmed by the minister himself.

Again, the false narrative created by fabricated comments suggests that the criticism of Poland’s support for the Belarusian opposition is cross-party and causes tensions both in Poland and Lithuania.

This time, fake news based on fabricated discussion is then published on another Belarusian Telegram channel and spread by channels of all the main state news outlets in Belarus.

Less than two weeks after the manipulated content was published on Telegram, Lukashenka’s regime suspended Belarus’s participation in the Eastern Partnership.

The report released by Mandiant in April also mentions an attempted phishing attack on “an important Belarusian blogger and activist.” It can be assumed it was one of the people running Nexta, a Telegram channel used by the opposition (on May 23, its co-creator Roman Pratasevich was hijacked from a scheduled plane en route to Lithuania and is currently being held by the Belarusian authorities). After the leak of Dworczyk’s emails, the creator of Nexta Stepan Putilo confirmed attempts to hack the authors of the channel and announced that the accounts of the Belarusian House, an organization of the Belarusian minority in Poland, were also targeted.

Successful exercises, harsh realities

The Polish email scandal that erupted in June is likely another result of the multifaceted Ghostwriter operation, which was launched years ago.

We already mentioned the attack on the website of the Polish War Studies Academy, identified as a part of the Ghostwriter campaign, that took place in April 2020. The Ministry of National Defence remarked that “as an independent entity, the website of the academy is hosted outside the infrastructure of the Ministry of National Defence, and the incident itself did not affect the functioning of the departmental ICT systems and the data processed in those systems.” The ministry downplayed the incident as isolated.

Already at that time, in spring 2020, the cyberspies at UNC1151 were posed to unleash a wave of phishing attacks on Polish targets. The first domains used in the latest series of attacks were registered in around March and April 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic provided fertile ground for all kinds of cybercriminals as remote work blossomed. Many people who had previously worked within secure office networks began using home networks and private electronic devices for their jobs – including some politicians and government officials.

Our analysis shows that one of the first phishing attempts made by these cyber criminals (in June 2020) involved the spoofing of the domain poczta.ron.mil.pl. Until recently, this web address served as the login page for employees of Poland’s Ministry of National Defence working remotely. Its infrastructure is protected by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCBC), a body that secures both open and classified IT systems used by over 100,000 military-linked users, including soldiers on foreign missions. A month later, another domain was registered – with a different extension but still very similar to the original.

It remains unclear whether any such attacks were successful.

At the end of May 2021, just a week before the Polish public learned about the leak of Dworczyk’s emails, a team from the NCBC participated in a joint international training exercise based on a real-life scenario, fending off simulated cyberattacks on the website of Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Embassy of the Netherlands in Lithuania: “The attackers posted fake content aimed at destabilising the political situation in Europe. […] There is a reasonable suspicion that the computers and smartphones of the diplomats of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Poland, and Lithuania have been compromised by the adversaries.”

A unit responsible for cybersecurity at the Ministry of National Defence boasted that “within 48 hours, a team led by an officer at NCBC identified compromised devices, determined the functional role of the malware and the ways it spread.”

The authors of the note concluded: “Luckily, it was only a successful exercise.”

Despite such successful exercises, the Ghostwriter hackers had already moved a step closer to achieving their goal – further destabilizing the political situation in Europe.

Vasya targets the Ukrainian army

After failing to gain access to Ministry of National Defence inboxes, the attackers reached for lower-hanging fruit. Over a period of 12 months, they registered dozens of domains used to carry out phishing campaigns. Many of them were designed to steal passwords from the users of popular Polish email services such as wp.pl, interia.pl, and onet.pl. The campaign was surprisingly effective: several hundred victims – including Marek Suski (a member of the Parliamentary Intelligence Committee) and Dworczyk, took the bait, providing the attackers with the passwords to their private email accounts.

We examined information from WHOIS records, which provide details about internet domains, and cross-referenced it with data from various sources such as reports from cybersecurity companies and threat exchange platforms. We analyzed over 200 domains linked to phishing attacks carried out in 2018–21. Dozens of them were used in Poland in a series of cyberattacks between May 2020 and July 2021. Some of these domains were included in Mandiant’s last report on the Ghostwriter campaign; the experts tracked them back directly to UNC1151.

In April 2021, after an attempted attack on the email accounts of Bundestag MPs, Hakan Tanriverdi, a journalist working for the German public broadcaster, looked into the email campaign targeting German MPs. The emails included a link to a domain that spoofed a German internet provider. He spotted a pattern: the same registrant was linked to over 30 other domains. Mandiant confirmed his finding, noting that these domains were directly traceable to UNC1151.

We followed this lead closely: first to non-existent addresses in Kyiv and the Altai Krai in eastern Siberia, where shadowy registrants listed as “Vasya” and “Yun” registered dozens of domains and subdomains for the sole purpose of stealing credentials.

Many of these domains impersonated some of the most commonly used online services – Gmail, Google Drive, Facebook, Twitter, and iCloud – as well as Polish email services such as wp.pl and onet.pl. Interestingly, the list also includes such targets as the aforementioned Polish Ministry of National Defence and Ukroboronprom, a Ukrainian defence conglomerate. One of the oldest domains in this cluster, registered in March 2020, spoofed the website of the Ukrainian army.

We tracked down other clusters of domains that followed the same pattern. An almost identical batch of domains was registered in Poland; this time, the registrant was masked, but the fact that they all contained the same typo distinguished them (“Warazawa” instead of “Warszawa”). We identified yet another cluster of domains registered in Bielsko. We confirmed that these clusters included the domains at the source of Michał Dworczyk’s hack-and-leak scandal, as well as the domains used to harvest credentials for Ghostwriter activities. The domain used to successfully targeted Dworczyk’s account on wp.pl even shared the same IP address as the previously mentioned domain that spoofed ron.mil.pl (which was officially attributed to UNC1151 in Mandiant’s latest report).

The domains from all these clusters, registered between spring 2020 and summer 2021, seem to have been created and secured using the same know-how. They share the same domain extensions and anonymization methods. In most cases, the servers are masked through Cloudflare, a content delivery network. This means that instead of connecting visitors to the attacker’s server, it connects them to a copy located on Cloudflare’s servers. In other words, anyone trying to track down the website creator using its IP address will lose trace of it in one of the 93 countries where Cloudflare servers are located. The identities of all domain registrants are also masked using the same anonymization methods (even though the registrants probably used false identities anyway). The registrants have honed their know-how: from early 2021 on, the only information we could find in WHOIS entries is the registration country (currently Iceland). Yet, the domains created during this period share enough distinctive features to spot patterns giving credibility to the suspicion that the same actor is hiding behind them all. We have identified over 30 such domains intended for use in Poland alone.

One of the most recent attack attempts we managed to trace originated from a domain registered on June 9, 2021, disguised as a firewall configuration. As we found out, the targets were the official email accounts of Polish MPs. The domain was redirecting to a website that mimicked the Lotus login panel, but parliamentary spam filters detected and blocked this attempt (the Polish Parliament uses IBM’s Lotus for email). However, Dworczyk’s official Sejm email account (Dworczyk is also an MP) was successfully breached anyway. A print screen with the content of his parliamentary inbox, accessed on June 14, was published on the Polish Telegram channel on July 1. The Internal Security Agency (ABW) confirmed the same attackers also breached the parliamentary email accounts of 10 other MPs from different parties. For now, we can only guess how these hackers finally accessed these MPs’ official email accounts – but Wirtualna Polska journalists revealed that there are serious email security vulnerabilities of both the Polish Parliament and many government institutions services.

Why would a group famous for publishing embarrassing content or sophisticated fake news on the hacked social media accounts of Polish MPs (as described in the first part of this article) also aim its sights at more difficult targets such as the Ukrainian military or defence projects? We assume that when it comes to such activities, including the attacks on the website of the War Studies Academy and the Ministry of National Defence, there is more than meets the eye: they may be part of a larger reconnaissance mission meant to scout out infrastructure and pave the way for more complex attacks. By performing such “security checks,” closely monitoring the response, and gaining access to the accounts of infrastructure users, attackers can prepare for more serious operations.

Old tricks from the GRU playbook

The Mandiant report revealed that UNC1151 was already setting traps for internet users in 2018, when it used inactive domains with the .ml and .tk country codes, the extensions of Mali and Tokelau. They are popular with cybercriminals because they can be registered free of charge. Many phishing attacks from that period originating from those domains are now considered to be the work of UNC1151. They targeted Ukrainian email accounts, but we were drawn to an address created in April 2018 with the clear intention of stealing data from the address employees used to log into their email, poczta.mon.gov.pl. Today, ron.mil.pl is used for that purpose. In 2020, it too came under attack from UNC1151.

The fake address mon-gov.ml (with a hyphen instead of a dot) redirected to another interesting website that contains some clues about the activities of a different group of cyber threat actors.

Phishing domains are usually short-lived; their lifespans depend on how fast service providers or anti-spam filters respond to the threats they pose. Therefore, cybercriminals must develop ever-more creative ideas for duping internet users. In 2018, UNC1151 used the address http://poczta.mon-gov.ml/. This was a successful move – the domain was not deleted until October 2020. It was not the first phishing attempt on a website mimicking the website of Poland’s Ministry of National Defence.

In February 2016, an address created using the same pattern (poczta.mon-gov.pl; again, a dot was replaced with a hyphen) was used by other perpetrators to steal data from the Ministry of National Defence. Two years before that, in 2014, attempts were made using poczta.mon.q0v.pl. The domain mon-gov.pl was taken over by the Polish CERT, a government body responsible for cybersecurity, and g0v.pl currently belongs to a Polish user; both are therefore useless for would-be attackers.

Cybersecurity analysts have identified the masterminds of these earlier attacks as APT28 (APT stands for “advanced persistent threat”). This is one of the many aliases used by a group of activists calling itself Fancy Bear, which has been revealed to be a unit of the GRU, the Russian military intelligence agency.

One could say that such similarities in modus operandi might be a coincidence (after all, the possibility of impersonating mon.gov.pl is limited by a finite number of possible combinations) but when we take a closer look at specific domains, we can find more common patterns.

Mandiant says that the activities attributed to UNC1151 include attacks on email accounts used by the Kuwaiti army. We managed to identify the domain UNC1151 used to carry out the attack back in 2018. Cybersecurity experts at TrendMicro have said that an almost identical domain (with the only difference being the extension) was used by Fancy Bear in October 2015.

Analysts have been closely monitoring the activities of Fancy Bear for many years. The latest report produced by TrendMicro, which has been monitoring email phishing attacks since 2014, identified a new trend in the tactics, techniques, and methods of this group (which TrendMicro calls Pawn Storm). In May 2019, it began to impersonate its victims, sending infected files or links to password-phishing addresses to other people from their compromised accounts. The phishing domains used by Fancy Bear provided at the end of the report published in 2019 are nearly identical to those traced back to UNC1151 in 2018 (this time around, they used the .ml and .tk extensions).

Does this mean there could be a relationship between UNC1151 and Fancy Bear? There are a number of indications that there might be a link between their activities. On many levels, UNC1151 seems to be a faithful follower of the GRU playbook, with similar goals and methods.

UNC1151’s cyberespionage activities might serve various goals – the Ghostwriter operation, official Lukashenka regime propaganda, or intelligence recruitment. The information acquired might also be used in spy games or for blackmail.

Although such activities should have alarmed the entire counterintelligence sector in Poland long ago, they didn’t.

Hackers or artists

“Hackers are free people like artists. If artists get up in the morning feeling good, all they do all day is paint. The same goes for hackers. They got up today and read that something is going on internationally. If they are feeling patriotic they will start contributing, as they believe, to the justified fight against those speaking ill of Russia,” teasingly responded Vladimir Putin in 2017 to questions about the Kremlin’s interference in the US elections in 2016.

At that time Russia already had one of the world’s largest cyber armies – for several years, it had intensively recruited and trained young IT specialists and programmers, who quickly joined the ranks of civilian and military services, including the GRU and the Foreign Intelligence Service (SWR). Increasingly spectacular cyberattacks could be traced back to Moscow. At the same time, more and more advanced disinformation operations were carried out by the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg (nicknamed “the troll factory” by the press).

In 2016, NATO recognized cyberspace as a domain of operation, equal to that of land, sea, and air. A year later, fake news would become the Collins Dictionary word of the year.

The attacks carried out by Fancy Bear include the following (officially recognized) operations:

- Attacks on the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and its American counterpart (USADA), and at least four other anti-doping institutions; cyber attackers stole and published sensitive information about the health of nearly 250 athletes from 30 countries, reinforcing the Kremlin narrative about the unfair disqualification of the Russian national team from the 2018 Winter Olympics; at that time Fancy Bear “hacktivists” were disseminating stolen documents while maintaining the appearance of “bottom-up” activities.

- An attempt to infiltrate the infrastructure of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which investigated the use of chemical weapons in Syria and the use of Novichok to poison Sergei Skripal (2018), a former GRU agent who had collaborated with British services. This attempt was foiled by Dutch intelligence.

Both attacks were so well documented that in October 2018, the US Department of Justice indicted seven Russian intelligence officers identified as members of GRU Unit 26165.

A separate indictment was filed in connection with the attack on the Hillary Clinton campaign – according to investigators, as many as 12 people, members of two cyber-espionage groups (Sandworm and Fancy Bear), were involved in the attack.

Presidential candidate Hilary Clinton during a rally just days before the election. Phoenix / U.S. – November 2, 2016. Source:

Autor: Rebekah Zemansky / Shutterstock.com

The Muller Report details the attack carried out by several groups. The operation began with a massive phishing attack launched by Fancy Bear against members of the Democratic National Committee (DNC). First, 50,000 email messages from John Podesta’s account were leaked (Podesta was Clinton’s campaign chief). At the same time, rather careless victims allowed hackers to gain access to the DNC’s internal network, who then uploaded software that logged keystrokes and screenshots.

Meanwhile, a second group began to disseminate stolen email messages via a specially created DCLeaks website. It sent them to the media under the guise of a fictional hacktivist, known as Guccifer 2.0, who even granted interviews.

The disinformation campaign that accompanied the publication of the cache of messages, which included both authentic and fake emails, buried Hillary Clinton’s chances of becoming US president.

Clinton’s official Department of State email account was also targeted, but two-step verification was enabled and effectively blocked the attack. At the same time, it was revealed that Clinton, used a private email address and private server for state affairs during her tenure as US Secretary of State. FBI director James Comey called this behaviour extremely careless despite the use of two-step verification. Neither Mateusz Morawiecki nor Michał Dworczyk learned any lessons from the Clinton scandal: five years later, they were caught governing Poland using their private email accounts.

It is interesting to note that an investigation after the attack on Clinton’s campaign revealed that apart from the Fancy Bear and Sandworm groups, another (third) Russian unit had access to the DNC servers at that time. The group, called Cozy Bear, is associated with the Russian SWR. It was probably an independent operation, part of a long-term espionage mission.

In the context of Dworczyk’s email scandal, the long list of attacks cybersecurity firms has attributed to Fancy Bear is also interesting.

In 2017, some documents stolen from the email account of journalist David Satter, a Kremlin critic, were tampered with and released as “leaks.” Satter was the victim of a wide-ranging phishing operation that targeted more than 200 recipients in 39 countries.

Fancy Bear may have also attempted to interfere in the 2017 French presidential election. Two days before the election, 20,000 emails concerning Emmanuel Macron’s campaign were leaked. The documents were posted on PasteBin, a service that allows the anonymous sharing of raw texts via a link. Still, the operation failed as the huge amount of data was released just before the election silence went into effect and hence did not get through to the media. The French authorities announced that the attack was so general and simple that “anyone could have committed it.”

However, there are many clues indicating that it was in fact a complicated operation. Analysts quoted by Le Monde suggested that although Fancy Bear had begun to prepare for the attack in March 2017, it discontinued the operation in mid-April, and another group, Sandworm, picked up where it had finished. Recall that Sandworm was allegedly responsible for distributing emails stolen by Fancy Bear during the DNC hack in 2016. In October 2020, the US Department of Justice announced that it had charged six identified hackers, members of the Sandworm group, who were simultaneously employees of GRU Unit 74455, in connection with cyber-espionage activities.

Apart from the attacks on the Macron and Clinton campaigns, which were carried out jointly with Fancy Bear, Sandworm was also responsible for cyber attacks committed “in the strategic interests of Russia”:

- attacks on Ukrainian power plants and transmission networks in 2015 and 2016;

- the global use of NotPetya, destructive malware that encrypted and wiped the disks of many electronic devices;

- an attack on the organizing committee of the 2018 Winter Olympics (for the same motives that made Fancy Bear leak athletes’ data); and

- phishing campaigns carried out against OPCW employees investigating the use of Novichok to poison Skripal, in the same year that officers from GRU Unit 26165 attempted to physically “plug” into its system.

Court documents related to the GRU agents involved in the activities of Fancy Bear and Sandworm, as well as reports published by cybersecurity firms, reveal the complexity of these multilayered operations. Sometimes they were carried out independently, at other times, in cooperation with other groups. They nearly always involve multiple techniques and methods: from massive or personalized phishing attacks to the use of malware or stolen electronic documents, and fake online personas or fake social media accounts.

The court files read like the plot of a sensational novel. When the hackers were unable to hunt down their victims remotely, GRU agents travelled around the world (from Lausanne to Rio de Janeiro) to physically hack target infrastructure (for instance, by connecting to a hotel Wi-Fi network). However, the basic tool was not very sophisticated phishing.

Cybersecurity firms have long examined the relationship between Fancy Bear and Sandworm. In many cases, the two groups cannot be clearly distinguished from each other. Analysts have described Sandworm as “a more specialised group, which carried out high-risk operations, particularly when the time was of the essence.”

In 2017, Russian Insider wrote about Fancy Bear: “[Unlike Sandworm], Fancy Bear is rather primitive – it carried out mass phishing campaigns, waiting for someone to click the link and share their password. The main task of Fancy Bear was to gain access to information that was then used for political purposes. For example, the documents obtained were modified, compromising information was added, and then posted on various websites owned by pro-Kremlin ‘activists’, and later promoted by the Kremlin media and troll farms.”

The activities of both groups required, as Russian Insider stressed, permanent well-trained staff and significant financial resources. They were clearly beyond the reach of lone wolf cybercriminals. The court files on the GRU agents indicate that both groups were based at the same Moscow address, in a building owned by the Russian Ministry of Defence.

Are the members of UNC1151 just skilled followers of the GRU playbook with no direct links to Russian intelligence services? In the cyber-espionage world, where groups cover up their tracks with false flags (e.g., Fancy Bear impersonated Ukrainian hackers or ISIS supporters), anything is possible, but it seems unlikely.

Let’s now compare the resources used by Fancy Bear and Sandworm revealed by American investigators and the scale of the operation currently taking place in Poland. The Polish operation, attributed to UNC1151, required

- creating a database of over 4,000 non-random targets, obtaining their private email addresses and, in many cases, collecting information about members of their families;

- registering several dozen domains for operations in Poland (the group was also active in other countries);

- analyzing the content of hacked email accounts (probably more than 700 accounts might have been taken over), accessing associated social media accounts, and possibly also viewing their content;

- according to the Mandiant report, the group is also capable of using malicious software and additional skills; and

- carrying out targeted disinformation campaigns and knowing the specifics of the Polish media landscape.

To sum up, this is not something that a few freelancing hackers could have done “out of a basement.”

The Mandiant report states that at this point the activities of UNC1151 cannot be linked to any previously tracked groups. However, German public television journalist Hakan Tanriverdi revealed that German intelligence services had informed a Bundestag committee that GRU units were behindGhostwriter.

How the Polish services failed to uncover Ghostwriter

In response to the deepening public confusion surrounding the case, on June 22, the spokesman of the minister-coordinator of the Special Services issued a statement in which he announced that the attack on Dworczyk’s email account was part of the Ghostwriter operation, the focus of a report we published on vsquare.org at the end of March.

“The list of targets of the socio-technical attack carried out by the UNC1151 group included at least 4,350 email accounts that were used by Polish citizens or were provided on Polish email servers. At least 500 users [their number has since exceeded 700] responded to the information prepared by the attackers, which significantly increased the probability of the aggressors’ actions being effective […] The list of 4,350 attacked email accounts includes over 100 accounts used by people who performed public duties. […] The list also includes an email account used by Michał Dworczyk,” the statement reads.

Why was the government alarmed only after Dworczyk’s email scandal broke out? If the latest attack is another outcome of the Ghostwriter operation, the government’s cybersecurity forces should have been aware of it much earlier.

What did the secret services really know about the attack and when did they first learn about it? Shortly after the scandal erupted, we revealed in OKO.press that the first warning signs about a series of attacks appeared in the autumn of 2020. After the email accounts of the Ministry of Family and Social Policy Marlena Maląg and MP Marcin Duszek were hacked (between October and December 2020), the case was examined by the army’s cybersecurity unit (CSIRT MON).

In December, the Critical Incidents Team at the Government Security Centre (RCB), which is responsible for threat analysis and crisis management, convened. During the meeting, Col. Konrad Korpowski, head of the RCB, allegedly asked whether the hacking campaign should be considered a critical incident. It was decided that it should not be. Six months later, Korpowski’s CV, which had been sent to Michał Dworczyk’s private email account, was published on Telegram.

In January, the Chancellery of the PM sent an online brochure to all MPs on how to protect their accounts against cyberattacks.

In early March 2021, a note on cyberattacks, jointly signed by the Cyber Incident Response Teams found its way to the desk of Marek Zagórski, at that time the Cybersecurity Plenipotentiary at the Chancellery of the PM. But no action was taken for another three months.

In the meantime, at the end of April, Dworczyk’s associate Karol Kotowicz notified the Cyber Incident Response Teams that a document from his email exchange was published on Agnieszka Kamińska’s Twitter account.

However, by June no one had yet discovered that in early February someone had set up a Russian-language channel on Telegram. The channel began to publish documents that allegedly originated from within the Polish government.

The Polish-language channel was created on June 4 but went unnoticed until June 8. The public learned about the existence of the channel from the Facebook account of Dworczyk’s wife (which had also been taken over). These methods resembled those used in the past as part of the Ghostwriter operation.

The channel published new emails and documents from Dworczyk’s hacked account almost every day until it was shut down (after gathering over 9,900 subscribers).

On June 15, the Critical Incidents Team convened again; this time, it agreed to rank the cyberattack as a critical incident. On the same day, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki submitted a motion to convene a closed session of the Polish Sejm.

On the morning before the session, the Government Crisis Management Team was to hold another meeting, where representatives of cybersecurity services would gather. According to unofficial sources, the initial plan was to immediately check whether MPs’ accounts were on the list of attacked emails. The Chancellery of the Sejm had even set up a special computer to run the check. But at the very last moment, the plan was abandoned.

“Someone close to Kaczyński [PiS leader] had probably looked at the list of potential targets of phishing attacks and realized that it included more of our politicians than those of the opposition,” one of our sources closely linked to PiS told us.

Instead, it was decided that the police should disseminate leaflets on cybersecurity prepared by the Chancellery of the PM; all those whose email accounts were on the list of phishing attacks received special letters (including people whose accounts had not been compromised).

On June 10, the District Prosecutor’s Office in Warsaw launched an investigation into the unauthorized accessing of Dworczyk’s email account. The Polish government also notified NATO about a cyber operation targeting Poland. Both Telegram channels were shut down on July 15 but resurfaced several hours later.

Nobody knows what new twists and turns the next chapter authored by Ghostwriter will bring.

Konrad Szczygieł, from the Reporters Foundation, contributed to this report.

Read in Polish on tvn24.pl

Anna Gielewska is co-founder and editor-in-chief of VSquare and co-founder of Polish investigative outlet FRONTSTORY.PL. She is also vice-chairwoman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). A journalist specializing in investigating organized disinformation and propaganda, Gielewska was the John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2019/20) and has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2015, 2021, 2022) and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Award (2021, 2023). She was the recipient of the Novinarska Cena in 2022.

A senior OSINT researcher and data analyst at FRONTSTORY.PL, Julia Dauksza has participated in many cross-border investigations. Previously, she collaborated with NGOs in Poland. She has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2021, 2022). She was the recipient of the 2023 Bertha Challenge Fellow.