(Follow The Money)

Illustrations: Leon de Korte

(Follow The Money) 2024-05-30

(Follow The Money)

Illustrations: Leon de Korte

(Follow The Money) 2024-05-30

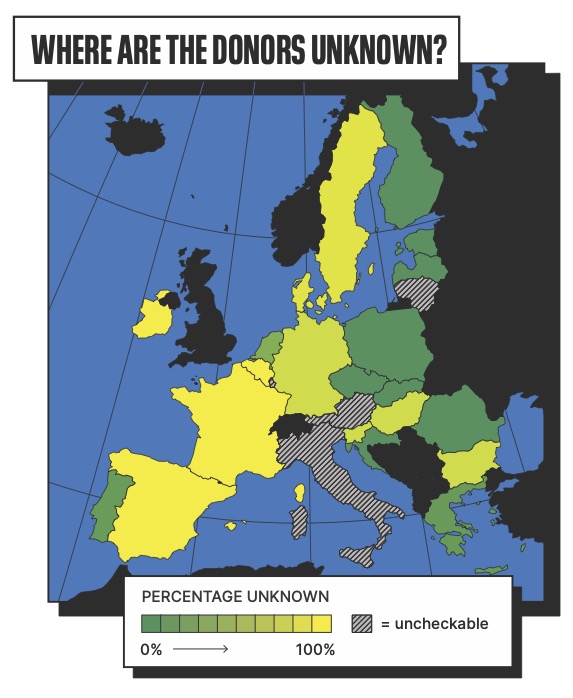

The donors behind almost three quarters of political donations in the EU are hidden from the public. Germany’s to blame for most of it.

Political parties in the European Union received almost a billion euros in donations between 2019 and 2022. For hundreds of millions of euros, the public doesn’t know who donated the money. The lack of transparency is biggest in powerful western European countries like Germany and France. In central and eastern European countries – most of which joined the EU in the decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 – the accounts are much more transparent, an international investigation led by Follow the Money shows.

For Follow the Money’s cross-border project Transparency Gap: The Funding of Political Parties in the EU, VSquare, together with 25 other outlets and 50 journalists, conducted an in-depth analysis of where parties in the EU get their money from. In the runup to the European elections, the project scrutinised the incomes of almost 300 political parties, diving into 1,200 financial reports and more than 500,000 donations to uncover how political parties are financed, who funds them, and how transparent the accounts are.

- Most countries in the European Union have public records of the donations political parties receive, to provide information for citizens about who funds these parties. These rules intend to promote integrity, transparency and accountability in democracies.

- Only for 3 out of every 10 euros that are donated the name of the donor is made public. Between 2019 and 2022 over 660 million euros in donations the origin is hidden.

- In Europe, each country has its own rules. Sometimes every single euro is accounted for and all the donors are named. But more often than not, large parts remain hidden and it is unclear who gave money to the political parties.

- For the first time, a Europe-wide consortium of investigative journalists has collected and analysed 12,000 financial reports and some 500,000 individual donations, shining a light on the financial revenues of political parties.

- Media partners in all 27 EU member states, plus the United Kingdom, contributed to this reporting. Among others, The Guardian, Papertrail Media from Germany, Spanish newspaper El Pais, and VSquare joined this effort.

It looks like the Iron Curtain is still dividing Europe – at least when it comes to being transparent about who is bankrolling political parties.

As Europeans head to the polls to decide on the new European Parliament between 6th and 9th of June, they don’t all have the same access to information about who funds the political parties.

The over 200 parties that were analysed – all have a reasonable chance of winning at least one of the 720 seats in the next Parliament – received 941 million euros in donations between 2019 and 2022. For 664 million euros of this, it’s unclear who sent in the money.

The picture that emerged: The countries that transformed from communist one-party states into democracies in the early 1990s embraced best practices. For the countries on the western side of the curtain that came down 35 years ago, a lack of accountability is still the norm. This means that citizens only have limited information about the individuals, companies, and other organisations that fund political parties.

The worst offenders are political parties in Germany: some 75 per cent of the anonymous donations in the EU go to German parties, the investigation found.

“If you look at the numbers that are available and the transparency of the finances of political parties and their candidates, the overall picture is very disappointing,” said Belgian political scientist Wouter Wolfs. “It is just not sufficient. … In an atmosphere in which politics in general and certain institutions in particular are already under pressure, this is fundamentally problematic.”

Trust in politicians and the political parties is low. Europeans rank political parties as most likely to be corrupted, well ahead of private companies, financial institutions, and the public sector. This is especially dangerous in a political climate where distrust can boil over into anger and even violence; several German politicians were attacked during campaign events over the last few months, and Slovakia’s prime minister barely survived being shot earlier this month.

According to the Eurobarometer, an EU-wide opinion poll, 6 out of 10 Europeans think corruption is rampant amongst political parties. Even more worry there is a lack of supervision and transparency concerning the finances of the parties.

The investigation brought to light a striking lack of transparency in Germany. For example: The populist right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland reported they received 6.4 million euros in donations in 2022. But the public records of who gave them money only name donors who, in total, gave 1.3 million euros. This leaves a gap of 5.1 million euros – or 80 per cent of their total income from donations.

This comparison, done for 231 political parties in Europe between 2019 and 2022, gave startling results.

Hiding behind anonymity

In France and Belgium not a single name of donor is made public.

In France, that’s because of privacy concerns. “Information relating to the identity of a person making a financial donation for the benefit of a political party is likely to reveal their political opinions,” a spokesperson from the authority tasked with auditing the accounts of political parties in France wrote in an email. Revealing the name of a donor is “therefore, subject to the confidentiality of their private life.”

This means that the public doesn’t know who is behind the 47 million euros that went to 11 national parties in the span of four years. And even this figure is just the tip of the French iceberg: many small regional and local parties also receive a lot of donations – the total sum of anonymous donations in France is three times as high, according to government data.

“It is the first-mover disadvantage,” Wolfs explained, referring to the western European countries that became democratic in the 19th and early 20th century. “In the old democracies the thinking stopped and no effort was made to update or modernise. When it concerns the transparency of political funding they are really not doing well.”

Sometimes it makes sense to protect the identity of donors, argued Fernando Casal Bertoa, associate professor at the University of Nottingham, for example in an authoritarian country where people supporting the opposition are in danger of being persecuted.

But for countries in the European Union that argument doesn’t make sense, he said.

“In France, which is a consolidated democracy, [keeping the identity secret] should not happen,” he said.

In Spain, the situation is similarly intransparent. There, the names of donors are only published if the donation is over 25,000 euros. Auditors and political parties confirmed to the journalists’ collective that not a single donation above this threshold has been made since 2015.

And there’s a loophole to circumvent even that rule: Any person affiliated to a party can give over 25,000 euros – and in that case, the donation rules do not apply. Politicians and party affiliates pay millions of euros into the coffers of the parties. The party of prime minister Pedro Sánchez, the social-democratic PSOE, pockets over 11 million euros each year – without having to disclose who the actual donor is.

In Europe’s biggest economy, Germany, there’s also a high threshold. The names of donors are only disclosed if someone or some company transfers more than 10,000 euros to a political party.

Unlike in Spain, thousands of them do.

But even more money flows into the coffers of the German parties in smaller amounts. Parties are allowed to accept amounts smaller than 500 euros without knowing where the money comes from. If the donation is anywhere between 500 and 10,000 euros, the party needs to know who gave them the money. While this needs to be reported to the parliament that can scrutinise the donations, the rest of society is kept in the dark.

From 2019 until 2022, German parties received a staggering 641 million euros in donations.

For 495 million of this, or 78 per cent, the name of the donor remains a secret.

In November 2023, German parties launched the most recent attempt to make the German system more transparent. They wanted to lower the threshold, but failed because of opposition from Christian democratic CDU, the party of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The coalition could have made the reform possible, but decided not to, citing common practice to have all parties on board before adopting rules that concern all parties.

“One crow does not peck the other’s eyes out,” said political scientist Michael Koß of Leuphana University in Lüneburg. (He added that Die Grünen are a partial exception because they seemed to genuinely want to change the rules.)

Another way to limit the influence of donors over political parties is to set a ceiling for the amount they are allowed to donate.

“This helps to avoid that parties become too dependent on a number of very specific donors,” political scientist Wolfs said.

But Germany doesn’t cap donations, and neither do seven other countries: Denmark, Sweden, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Estonia, and Bulgaria. All the others set a ceiling, but the limits vary between 500 euros – in Belgium – and 300,000 euros in Slovakia.

“Any rule stands or falls on the enforcement and controls.” Part of the issue, Wolfs said, is that authorities responsible for checking the financial accounts of parties aren’t always independent.

“In some countries, the parliament is responsible for auditing the finances of political parties, which means the parties are controlling each other,” he said. “There is a tendency to turn a blind eye.”

And even when an independent body exists to check finances, there’s another problem, Wolfs said: almost all auditors are underfunded.

In Spain, for example, the Tribunal de Cuentas is responsible for auditing the accounts. They have been complaining for a long time that the staff of 40 is overburdened and cannot keep up with checking the financial reports of the more than 30 national and almost 200 local parties. They’re still auditing the 2020 finances. Within the German parliament, just three lawyers are tasked to check the accounts.

The great divide

The Baltics seem to be the poster child when it comes to transparency.

Estonia is perhaps the most transparent country of the EU. The names of the almost 50,000 members of the country’s 13 parties and the monthly fees they pay are made public. Donations as low as 1 euro are visible to everyone. The lists of names and amounts are published every three months.

In most central and eastern European countries, the picture looks similar. Each year, all the donations and their donors are published; they are often buried deep inside financial reports and scanned upside down, but they are public.

Before these countries joined the European Union in 2004 and 2007, the bloc set some conditions for them to implement reforms in line with democratic values. Only after having done that could they benefit from free trade, free movement and the full benefits of EU membership.

“The fact that these countries wanted to become part of the European Union was a strong incentive,” said Wouter Wolfs, political scientist at the Leuven University. “This way they could show they took corruption prevention seriously.”

Source: Follow The Money

But transparency doesn’t mean that there are no problems related to influence peddling by wealthy donors, payments made in return for favours, or misuse of donated funds in Central and Eastern Europe.

For example, Mircea Drăghici, the former treasurer of Romania’s largest party, the PSD, was sentenced to two years in prison after admitting to using party subsidies for exotic holidays. Drăghici used public funds his party received to pay for luxury holidays in Bali, Singapore, the Emirates or the Dominican Republic for his family and neighbours.

Even in Estonia and Latvia, where detailed information like the date of birth of a donor is made public, there are several cases where, it turned out, the named donor was not the actual person giving the money. Businessmen who needed favours from politicians used strawmen to hide their identity.

Still, the high level of transparency makes it easier to scrutinise where potentially dubious donations come from.

The paper files

In the west of the European Union, it’s not only the powerhouses of Germany and France that are intransparent.

In Portugal and Luxembourg the records can only be accessed by physically going to the court of auditors or national parliament, and even then it is forbidden to make the names of the donors public because of “data protection”. In Luxembourg, the parliament insisted Follow the Money sign a non-disclosure agreement agreeing to not make the lists of named donors public.

When visiting the offices of the authority tasked with auditing the accounts of parties in Portugal, journalists found about twenty boxes full of receipts from the communist party and much more detailed financial accounts than are available online. It took two weeks to go through it all – they weren’t allowed to take pictures or recordings, the digital files could only be accessed on a computer which was not connected to the internet, and officials took turns to watch everything they did.

Follow the Money’s media partner Público discovered that Chega – the far-right populists who are the third largest party in Portugal – reported only 236 euros from identifiable donors in 2021 and 2022. The remaining 323,656 euros came from anonymous sources, mostly through IfThenPay, a Portuguese fintech company.

In both countries, the financial records are available – but not in a transparent and accessible way.

In Belgium, the records of the 1 million euros in donations the parties accepted between 2019 and 2022 are collected in boxes labelled “secret”, held in a room tucked away in one of the buildings of the parliament. Only the 17 lawmakers who are members of the budget control commission are allowed to see them.

“Nothing forbids parties to publish more detailed information than required by law on how much and from whom they receive donations,” said political scientist Casal Bertoa. “But almost nobody does.”

Bad accounting

But high thresholds – or lax rules – aren’t the only obstacle to identifying donors.

The Nationalist Party in Malta is the political home of Roberta Metsola, the current president of the Parliament. They have not submitted a full financial account since 2020, which is a breach of the law. This is due to a “lack of human resources”, a party spokesperson said.

Also in other countries, it takes parties a long time to publish their financial statements. In Austria, for example, the most recent ones available are from 2021. In Lithuania, despite its otherwise transparent system, the situation is even worse: Political parties (and the church) are by law exempted from publishing detailed annual financial accounts. In Greece and Ireland, the 2022 donations are still not made public.

“Sometimes it takes a year, a year and a half, two years or more before that information comes online – or even becomes available,” said Wolfs. “Of course, if these donations are made in the context of an election campaign, this means that accountability comes much too late.”

But there are also structural issues: regional chapters of the parties or party-affiliated foundations can receive donations and send that money to their national party – obscuring the actual sources of the funding.

In Italy, for example, rules on reporting donations are very strict – in theory. But parties seem to have found a way around them: Companies and individuals tend to donate not directly to the parties, but to other related entities, such as political foundations or electoral committees. This effectively creates a parallel system for raising funds and organising events to benefit political parties.

When the government created new rules in 2019 to force them to publish the names of their donors, the foundations turned themselves into non-profit organisations and could, again, keep secret from whom they received money: non-profits are exempt from the disclosure rules.

And this can be a breeding ground for corruption.

A recent investigation involved the president of the Liguria region, Giovanni Toti. He allegedly arranged building permits and favours in exchange for money to fund his election campaigns. Toti was put under house arrest earlier this month.

“Non-transparent funding of politics paves the way for serious corruption incidents like this,” said Federico Anghelé, director of The Good Lobby Italy.

The Italian NGO has been proposing to strengthen controls and create a single digital platform to monitor the income and expenditures of politics – without much success.

“For years we have been ignored, and this is the sad result,” he said.

There is a clear reason for the lack of transparency and the fact that for 71 per cent of the donations it is unclear who the actual donor is: it seems parties’ are reluctant to change.

It’s only when things get shaken up, when there’s a scandal or when the country goes from being a one-party communist state to being part of the European Union, change happens.

Only then the reluctance of politicians and their parties to be more transparent about their funding can be overcome, several experts told FTM.

“The problem with the funding of political parties is that in general parties and politicians make rules in the public interest,” Wolfs said. “But when it is about the financing of political parties they are involved themselves, the parties are the beneficiary. It makes it very hard for them to change the rules if it is not in their own favour.”

Emma du Chatinier, Alistair Keepe, Leonie Kijewski, Nathan Niedermeier and Sarah Pilz contributed to this reporting, as did all the partner media from across Europe.

Casal Bertoa echoed the assessment.

“Parties are not interested in transparency,” he said. “They think that is going to limit them, to impede their deals in smoke-filled rooms.”