Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK.sk)

Anastasiia Morozova (Frontstory.pl)

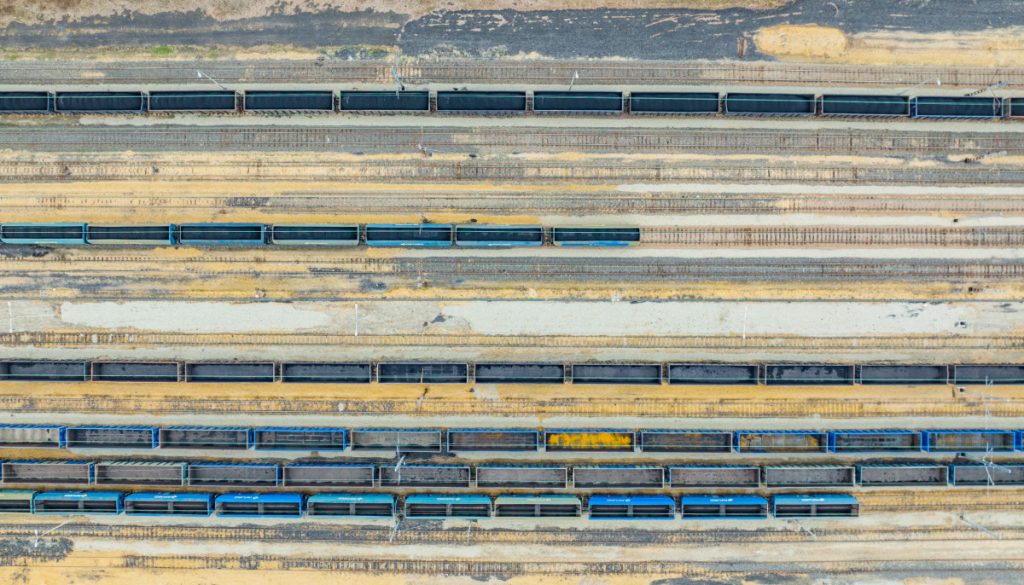

Photo: Robert Neumann / Forum 2023-09-23

Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK.sk)

Anastasiia Morozova (Frontstory.pl)

Photo: Robert Neumann / Forum 2023-09-23

Ukraine’s counteroffensive against Russia has a secret battlefield, one nestled within NATO territory. This strange battle is over the many hundreds of Russian and Belarusian rail cars stranded near the European Union’s border with Ukraine in countries such as Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland. These wagons, which used to carry all kinds of goods from Russia and Belarus to the EU, were stranded on NATO soil after Russia’s attack on Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Of course, the fate of these rail cars will not change the course of the war. Nevertheless, these piled up wagons near Ukrainian border crossings have been blocking tracks, hence limiting the throughput and slowing down Ukraine’s trade via rail with the European Union, hindering the country’s international commerce in a time of need. Moreover, if seized by Ukraine, these Russian and Belarusian rail cars could directly contribute to the attacked country’s ability to supply its armed forces—as well as its civilian population, and economy.

The rail cars became stranded for two reasons. The main reason is that rail tracks in post-Soviet countries are not compatible with European standards. Russia and Ukraine use what are known as broad-gauge rails, meaning that the width between a pair of rails is approximately 100 mms wider (1520 mms) than in Europe. Whenever a train from Ukraine crosses into EU territory, goods are moved from broad-gauge to normal-gauge wagons. Then the original broad-gauge trains head back in the direction of Ukraine as they are unable to proceed further into the EU’s rail networks.

Dual gauge rails in Lithuania (1520 mm gauge: rails 1 and 3; 1435 mm gauge: rails 2 and 4). Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, in March 2022, Ukraine started to seize and nationalize Russian rail cars on Ukrainian territory, including those returning to Ukraine from the EU. This was made possible thanks to Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelensky signing of a new law “On Basic Principles of Compulsory Seizure of Property Rights of the Russian Federation in Ukraine.” “Approximately 16 or 17 thousand Russian and Belarusian railcars on the territory of Ukraine were seized by presidential decree and transferred to the army and Ukrzaliznytsia [or UZ, Ukrainian state railways] for use by court order,” a senior UZ official told us, adding that “the seized railcars earned us about a billion hryvnias” estimated, which was worth €30 million at the time. The confiscations were the second reason behind the piling-up of wagons: to avoid losing more rail cars, Russian and Belarusian cargo companies then decided not to return the remainder of their wagons through Ukraine and simply kept them parked inside the EU.

An investigation by VSquare with partners ICJK.sk and Frontstory.pl reveals how three of Ukraine’s Western neighbors have been struggling to solve this situation for almost one and a half years:

- In train stations in Hungarian towns at the Ukrainian border, almost 500 Russian cargo rail cars had gotten stranded, 300 of which are still occupying tracks and slowing traffic. Previously, Ukraine’s state railway asked Hungary in vain to free up the space by sending them those obsolete Russian wagons. However, rail cars are slowly dissipating: some were sent to Ukraine while others likely got back to Russia via Poland and Belarus.

- In neighboring Slovakia, around the same number of wagons got stuck creating the same situation. Most of those Russian rail cars were handed over to Ukraine by an American-owned company, and the same fate might await the remainder of the wagons. This has all been happening in silence due to the dubious legality of the move.

- Meanwhile, most wagons were stranded in Poland, the country most vocal in its support for Ukraine. However, despite our multiple efforts, Polish railway companies did not provide us substantial information on the fate of those cars. Earlier stories by tvn24.pl and Rzeczpospolita have revealed that some of the Russian wagons went back to Russia via Belarus, avoiding getting confiscated by Ukraine. Ukrainian officials told us that once they discovered this method, they made sure that Polish authorities would help them get the rest of the rail cars. However, our investigation also reveals that Russian wagons stranded in Hungary and Slovakia were also returned to their owners via roads on the Polish-Belarusian border.

Hungary: Absolutely no help to Ukraine

On June 6, 2022, a daily report sent by Hungarian state railways MÁV to the government described a near-critical situation in rail traffic at the Hungarian-Ukrainian border. The report, obtained by VSquare, says that “the track capacity of [the train station of border town] Eperjeske (the available space on the tracks for rail cars) has met its limit.” As many as 793 loaded wagons were occupying the broad-gauge tracks, leading to a lack of capacity and “resulting in the stalling of trains entering on broad-gauge tracks at the Ukrainian border crossing [of Solovka/Szalóka].”

The report was sent to the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office and heads of the Ministry of Innovation and Transport, among others. One of the recipients was government spokesman Alexandra Szentkirályi. She also happens to be the wife of Minister of Defense Kristóf Szalay-Bobrovniczky, a former businessman who has been a business partner of Russian state-owned rail company Transmashholding.

According to a source close to the Hungarian government with direct knowledge of the issue with the stranded Russian wagons, while the problem was absolutely obvious to both MÁV and Viktor Orbán’s government, they still refused to act. “The leadership of UZ has offered to take care of the situation, meaning that we free up the tracks by giving them those Russian rail cars. But, of course, we did not want to take on a conflict with Russia by letting Ukraine confiscate the wagons. So we turned down the offer,” the source added.

“Ukrainians wanted to put their hands on everything,” a Hungarian foreign ministry official commented, adding that Hungary did not want to deal with the situation so the Hungarian government opted not to interfere. “The legal situation was murky, we couldn’t and didn’t want to decide between Ukraine and the Russian owners,” the foreign ministry official added. “Indeed, the Hungarians have these wagons, and they are clogging up the border station, which prevents up to some extent the transfer of export goods. And the Hungarians do not want to give them to us,” a senior UZ official said. Hungary’s Ministry of Construction and Transport, responsible for rail transportation as well as overseeing MÁV, did not respond to our inquiry.

Kristóf Szalay-Bobrovniczky, minister of defense of Hungary. In 2019, his company bought 50% shares of Transmashholding Hungary. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Hungary’s government has maintained a close relationship with Vladimir Putin’s administration despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and has spent much of the past year and a half lashing out and trying to water down EU sanctions against Russia. Hungary also refuses any kind of military support to Ukraine, blocking EU military aid to the country while also preventing weapon supplies from crossing the Hungarian-Ukrainian border.

Valeriy Tkachev, deputy director of UZ’s commercial department, spoke publicly about the offer to transfer Russian rail cars from Hungary to Ukraine in a November 2022 Rail Insider article. “We will find a use for them in Ukraine and use them for transportation. And even if you do not transfer these cars, is there no place in the MÁV infrastructure to put them to standstill except at the border with Ukraine, occupying the already limited track development and creating obstacles for us to transfer cargo at the border?,” Tkachev told Rail Insider. At the time, because of the stranded Russian wagons blocking tracks on the Hungarian side of the border, the traffic situation was so bad that the number of accumulated Ukrainian rail cars on the Ukrainian side of the border (Batyovo) rose from 3800 in early November to 4650 in November 22, according to the article.

UZ’s traffic management department director Volodymyr Rushchak told Rail Insider that a majority of the rail cars are operated by Rail Cargo Hungaria (RCH), a subsidiary of the Austrian state-owned Rail Cargo Group. This was also confirmed to VSquare by the source close to the Hungarian government with direct knowledge of the Russian wagons issue. Moreover, according to the source, the leadership of MÁV was even drawing up an alternative plan to resolve the issue of the wagons based on the Austrian company’s possible involvement.

“You can only confiscate property from those you are at war with, but you can’t seize them from Austria,” the source explained. That was the scenario under discussion within MÁV at the time. The plan was to first bring the Russian wagons under Austrian ownership and put an Austrian flag on them, so that they could then be transported to Ukraine without the risk of being nationalized. However, it is unclear what happened to these plans, the source added. RCH denied any involvement in such plans to VSquare, while MÁV did not comment on this question.

Meanwhile, the stranded Russian wagons slowly started to dissipate, as the following list shows:

- February 24, 2022: 496 Russian cargo cars (RCH’s reply to VSquare)

- November 2022: 480 Russian cargo cars (UZ’s data, quoted by Rail Insider) or 462 rail cars (MÁV’s data, quoted by Rail Insider)

- June 2023: 402 Russian cargo cars (MÁV to VSquare)

- July-August 2023: 318 Russian cargo cars (RCH to VSquare) or 317 Russian and 9 Belarusian cargo cars (MÁV to VSquare)

MÁV told VSquare that these rail cars have been stored on broad-gauge tracks in three stations: at Eperjeske-Rendező, Záhony-Széles, and Tuzsér. “The number of wagons is constantly decreasing due to the actions of the contractor railway companies,” MÁV added. Without naming RCH, MÁV shrugged off the company’s responsibility, claiming that the wagons’ Russian owners have no contractual ties to MÁV but are clients of “rail transport companies.” MÁV also emphasized to VSquare that rail vehicles in Russia have been privatized and all Russian rail cars stranded in Hungary are privately owned, not state owned.

On the other hand, RCH also stressed that they are not responsible for these rail cars. “Rail Cargo Hungaria is the user of the Russian private wagons and not the operator,” they said, adding that, after shipments arrive, “the consignee indicated in the consignment note has the right to dispose of the wagons.” This means that companies receiving those shipments are responsible for them, and have the right to decide on the future of the wagons. RCH revealed that one of its partners eventually decided to send back 64 rail cars to Ukraine via rail, while others decided to transport 116 rail cars via road transportation. This is why only around 318 of the original 496 stranded Russian wagons remain in Hungary.

RCH didn’t elaborate on the route of the rail cars transported on road, but the Rail Insider article on the Hungarian situation mentions that, in October 2022, a Russian wagon’s platform was spotted being transported on a truck in Poland. The logic behind such a route is that the Russian owners can prevent Ukraine from confiscating their rail cars by sending them home through the Polish-Belarusian border. A source close to the Hungarian government confirmed that some Russian rail cars were indeed sent home that way.

Slovakia: US company sends most wagons to Ukraine

Just a few kilometers north of the Hungarian-Ukrainian border in Slovakia at the Maťovce-Haniska pri Košiciach and Čierna nad Tisou-Čop border crossings, the situation was exactly the same, at least initially. Since the war started, Slovak authorities, as well as state-owned and private companies, have had to deal with over four hundred broad-gauge wagons owned by Russian and Belarusian private companies (according to sources with knowledge of the Slovak situation, these were all privately, not state-owned, companies). These rail cars became stranded as their owners refused to direct them back to Ukraine.

“The problem with returning private Russian and Belarusian broad-gauge wagons to their owners arose in connection with the war in Ukraine. The owners of these broad-gauge wagons refused to direct them back to Ukraine. Broad-gauge wagons, however, cannot be routed by rail anywhere else than to Ukraine via the existing broad-gauge railway,” Silvia Kuncová, spokesperson of Cargo Slovakia (ZSSK Cargo), a state owned rail freight transport company, told VSquare partner ICJK.sk.

But there is also a legal problem as, according to EU regulation, rail cars from outside of the European Union cannot remain indefinitely on EU soil. However, it seems that exactly which EU regulation should be applied is a matter of interpretation. In Hungary, RCH consulted with the Hungarian Tax Office and came up with an interpretation that lets Russian and Belarusian rail cars park in Hungary forever, essentially. RCH told us that, according to their position, Article 251 of the EU Customs Code applies to the Russian and Belarusian rail cars, meaning that they can stay for 24 months, and that even that can be extended.

However, Cargo Slovakia found and applied a different and much stricter EU law. Kuncová explained that, according to the Slovak company, there was a 12-month deadline to deal with the situation: “As railway vehicles, Russian and Belarusian broad-gauge wagons were released into the regime of temporary use with full exemption from customs duty. The period during which they can be in this regime is 12 months (in accordance with Article 217 of Commission Delegated Regulation 2015/2446). Within this period, the wagons must leave the territory of the EU.”

According to ICJK.sk’s research, there were a total of 426 broad-gauge wagons (417 Russian, nine Belarusian) stranded in Slovakia at the beginning of the war. However, out of those, there are currently only 143 left in the country. These remaining rail cars are temporarily held in a Slovak customs warehouse and, so long as they are there, the 12-month deadline does not apply, according to the CARGO spokesperson. However, the storage is not free. There is a customs guarantee attached that must be paid by whatever company was the recipient of the goods originally transported inside said wagons.

But what about the other wagons? The spokesperson of CARGO confirmed that 265 rail cars (around 255 of which, according to our source, were Russian, with the rest being Belarusian) were transported from the EU via the existing broad-gauge railway to Ukraine and that they were taken over by UZ Ukrainian railways. Of course, Slovak authorities and companies knew about the Ukrainian law on seizing Russian property when they sent the wagons from Slovak territory back to Ukraine. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that their actions should be read as hidden support for the Ukrainian war effort.

The 12-month deadline was looming over the heads of those who were stuck with the responsibility of the wagons. A source from eastern Slovakia with knowledge of the matter explained to us that, especially before the war, many broad-gauge wagons arrived from Ukraine. But while CARGO was responsible for their transportation, when the wagons reached the recipient, they became the recipient’s problem. This was confirmed by CARGO spokesperson Kuncová: “In terms of international railway law, ZSSK CARGO loses any relationship to these wagons after handing over private Russian and Belarusian SR wagons to the receiver. For that reason, it cannot without the disposition of the owner of the wagon, or the original consignee, handle these wagons or move them.”

As the anonymous source explained to us, there is only one such recipient who could receive broad-gauge wagons in Slovakia, as the wide railway goes all the way to its area: the biggest Slovak steel manufacturer, U.S. Steel Košice, a subsidiary of United States Steel Corporation (U.S. Steel).

U. S. Steel Košice building in Slovakia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The source explained to us that U.S. Steel was stuck with wagons that were not just an obnoxious nuisance, but also a practical problem, as they were blocking their own capacities and space in the factory. Therefore, the private company did the only thing it could: it sent the wagons back to Ukraine, even without the consent of their Russian and Belarusian owners. The legal framework of such a solution is murky and nobody wanted to comment on that, either on or off the record.

“Our primary task is to ensure a continuous supply of raw materials that we need for the operation of the factory. We are currently doing this thanks to the extreme efforts of our buyers and partners around the world. The question of wagons is a partial problem in this, which we solve in such a way as to comply with all valid sanctions adopted in the EU and at the same time in the USA. However, we do not consider it appropriate to comment on detailed procedures related to our business,” U.S. Steel Košice spokesperson Ján Bača said in a response to our inquiries.

However, besides the 265 wagons handed over to Ukraine and the 143 awaiting for the unsure future in a Slovak customs warehouse, there were 18 which met a different fate. “ZSSK CARGO has information that some wide-gauge wagons were exported from the territory of the Slovak Republic in a different way (they were disassembled and transported by road through Poland, Belarus to Russia). However, this solution was beyond ZSSK CARGO. This was handled by the original receivers with the owners/keepers of the wagons,” the company’s spokesman told us. A senior UZ official is not optimistic about what will happen to the remainder of the Russian rail cars: “Hungarians and Slovaks are looking for ways to hold on to these Russian wagons that have not been transferred to us. Slovakia – they still adhere to some Russian requests. Russians must have something there.”

Poland: Ukraine intervened to get the wagons

The problem of piled up Russian and Belarusian rail cars was the most serious for Poland. After the invasion, many Ukrainian trains stopped as they neared Izov on the Lvov Railway and LHS lines (LHS, or Linia Hutnicza Szerokotorowa, is responsible for the broad-gauge railways in Poland, and it is linked to Polish state railways PKP). They could not enter Poland because the tracks were occupied by the empty cars of the Belarusian Railways and others belonging to owners from the Russian Federation. The Belarusian and Russian wagon owners deliberately did not take steps to free up the LHS tracks.

LHS railway in Zwierzyniec, Poland, Source: Wikimedia Commons

At the beginning of April 2022, this traffic jam had already prevented 24.190 wagons from crossing the western border with Ukraine. The wagons mostly contained vegetable oil, iron ore, metal ore, chemicals, and coal. The case was reported by Ukraine’s state railroad company UZ.

Despite multiple requests for comment, LHS and PKP did not provide us with concrete information on the numbers of Russian and Belarusian wagons stranded in Poland after the invasion. Nor did they elaborate on how many of them are still in Poland; how many were sent to Ukraine (and subsequently confiscated by the Ukrainian government); or how many were transported through Belarus to the wagons’ original owners. Polish government ministries did not give substantial information either.

However, it has already been reported that, just like in Slovakia and Hungary, Russians and Belarusians found a way to get back at least some of their rail cars. According to a tvn24.pl investigation, a minimum of somewhere between 35-40 wagons were returned to Russia via Belarus. They were supposed to be on LHS railroad infrastructure as LHS manages the tracks in the eastern part of the country on the Hrubieszow-Slavkovo route. On February 1, 2023, LHS sent a letter to UZ with the numbers of the 16 wagons, informing them that they would be returned to Russia. The wagons did not return by the same route they took to Poland (via Ukraine), but were instead sent via Belarus. This way, Russian owners managed to prevent the Ukrainian government from confiscating some of their wagons.

LHS denied that the rail cars returned to Russia were at its disposal. However, the company is the only one that simultaneously manages rail traffic and infrastructure not only in Poland, but throughout the European Union. As a result, it is responsible for everything on the LHS lines. According to a letter obtained by tvn24.pl, the rail cars returned to Russia belonged to “Novaya Perevozochnaya Kompaniya,” one of Russia’s leading rail transport companies managed by “Globaltrans Investment plc.” Although this company is not directly subject to EU sanctions, it is on the Ukrainian government’s sanctions list.

Besides the unknown number of rail cars stuck in Poland that were eventually sent back to their original owners via the Polish-Belarusian border, according to VSquare’s tally, the number of Russian rail cars likely transported from Hungary and Slovakia through Poland to Belarus on trucks is at least 134. Polish authorities did not reply to our questions regarding why and how they authorized these transports through the country.

A senior UZ official gave a more detailed account of what happened. Initially, “there were cases when railcars were dismantled in Poland, loaded onto trucks and somehow transported to Russia. But then we tracked down these companies, and we stopped cooperating with such terminals and introduced a convention [sanction] on them,” the official said, claiming that this was just a small number of wagons that these firms managed to evacuate. After they identified these companies, UZ took measures against them and flagged the problem to Poland. Then “the rest went to us, Poland gave us everything,” and now, according to the Ukrainian official, “these wagons are working for the restoration of Ukraine.”

Błażej Adamski (Frontstory.pl) contributed to this investigation.

VSquare’s Budapest-based lead investigative editor in charge of Central European investigations, Szabolcs Panyi is also a Hungarian investigative journalist at Direkt36. He covers national security, foreign policy, and Russian and Chinese influence. He was a European Press Prize finalist in 2018 and 2021.

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.