Anita Komuves , Tamas Bodoky (Átlátszo)

Wojciech Cieśla (Fundacja Reporterów)

Graphics: Lenka Matoušková 2019-10-31

Anita Komuves , Tamas Bodoky (Átlátszo)

Wojciech Cieśla (Fundacja Reporterów)

Graphics: Lenka Matoušková 2019-10-31

Huawei is at the center of heated political debate around the world. There is a general assumption among experts on China, ICT (Information and Communications Technology) experts and politicians that the company uses its ICT devices to spy on its users and provide this data to Chinese government. Though there have been separate cases of Huawei breaches of consumer trust, however, no one has ever came up with bullet proof evidence of systematic abuse of Huawei devices.

Huawei highlights that unlike in the case of the USA and its NASA scandal, no surveillance and listening to European politicians has ever been proven.

The company is also in the middle of trade war between the USA and China, and has alleged that claims about its security flaws are just a way to slow down technological development of Huawei devices, which are considered by many to be far ahead of the rest of the world.

As always, the truth is much more complex and interesting, showing possible strategic thinking on the part of China for times of peace and times of war.

HUAWEI CASES

USA: Felix Lindner and Gregor Kopf gave a conference presentation at Defcon to announce that they uncovered several critical vulnerabilities in Huawei routers (models AR18 and AR29) which could be used to get remote access to the device. (July 2012)

USA: Huawei driver vulnerability uncovered by Microsoft. (November 2018)

Africa: African Union officials told the Financial Times that computer systems installed by Huawei in its headquarters had been transferring confidential information daily to servers in China between 2012 and 2017. (January 2018)

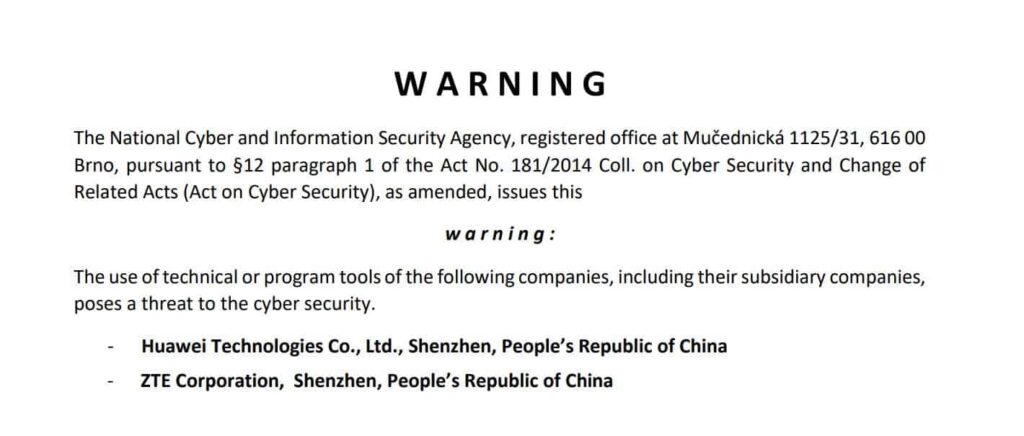

Czech Republic: National Cyber and Information Security Agency issued a warning: “The use of the hardware or software of the following companies, including their subsidiaries, constitutes a cyber security threat: Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China and ZTE Corporation, Shenzhen, China.” (December 2018)

UK: The Oversight Board of the United Kingdom’s government organization Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) found “serious and systematic defects” in Huawei software engineering and their cybersecurity competence. HCSEC also casted doubt on Huawei’s ability and competence to fix the security problems that were found. (March 2019)

Netherlands: Newspaper De Volkskrant, citing unidentified intelligence sources, claimed that Chinese telecoms equipment maker Huawei has a hidden “backdoor” on the network of a major Dutch telecoms firm, making it possible to access customer data. (May 2019)

Until December 2018, Huawei devices such as mobile phones, disk servers, and routers were widely used by Ministries, politicians, journalists, academics, police forces and other state stakeholders in Visegrad countries.

In Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, Huawei won public tenders to provide technical solutions to state infrastructure, including ministries, nuclear power plants and the police.

But some of the devices were distributed in much more private ways. They were given to carefully selected decision makers and opinion leaders as free gifts.

Shower them with gifts

According to a former Hungarian diplomat to China, part of Huawei’s strategy is to promote and spread their devices through generosity: “Huawei loves to take senior diplomats posted to China on lavish trips, to their research and development center, to Beijing and Shenzhen. They get the latest tablets, routers or cameras as gifts. They give constantly: it is not bribery, they do not expect anything in return, they just shower them with gifts all the time.”

The situation is quite similar in Poland, where journalists are frequently invited by Huawei to exclusive and lavish press trips in the biggest cities around the world. In October 2018 Huawei chartered a whole Boeing 737-800 aircraft to transport Polish journalists to the London launch of its latest smartphone.

The company also continues to organise press trips for Polish journalists to China which last several days.

Huawei pays for the whole trip, which includes plane tickets, transportation, accommodation in luxurious hotels, dinners in top restaurants, tour guides, and Polish-Chinese translators. New SIM cards are also distributed to journalists so they can bypass Chinese internet restrictions.

So why it is so dangerous for stakeholders to be using — and, to a certain level, depending on — on Huawei products, and what could possibly go wrong? Well… almost everything.

Photo: Isriya Paireepairit/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Technical Flaws

This year a US based company Finite State took a close professional and technical look at Huawei devices.

“We have undertaken a large-scale study of the cybersecurity-related risks embedded within Huawei enterprise devices by analyzing Huawei device firmware. (…) Our automated system analyzed more than 1.5 million files embedded within 9,936 firmware images supporting 558 different products within Huawei’s enterprise networking product lines,” the report stated. “The results of the analysis show that Huawei devices quantitatively pose a high risk to their users. In virtually all categories we studied, we found Huawei devices to be less secure than comparable devices from other vendors,” the authors concluded.

The report did not implicate the Chinese government in any spying or wrongdoing. There were no direct backdoors or special code snippets that would enable Chinese secret services to listen to private conversations of politicians, steal data or surveil high profile strategic meetings. The revelation was much more simple: the backdoors are not there YET.

Huawei responded with their own report on Finite State’s study: “We were surprised and disappointed by the unconventional approach of Finite State. We cannot determine whether Finite State obtained the software from legitimate channels or guarantee its integrity, nor has Huawei ever received any communication requests from Finite State. They made no contact with Huawei to assist them in their understanding and refused to provide a copy of their analysis before it was published. Sadly, this means what has been published lacks the insight, integrity and accuracy we would normally expect from a professional, serious and capable organization.”

Nevertheless, in an interview for Fox Business News, Huawei’s US Chief Security Officer, Andy Purdy admitted there might be some truth about the report and even carefully welcomed it: “The fact is, this is exactly the kind of report that’s generated when a product goes to a customer… This is exactly what you find… The good news is: this is exactly what’s necessary to make America safer in communications and 5G — independent verification of everybody’s products.”

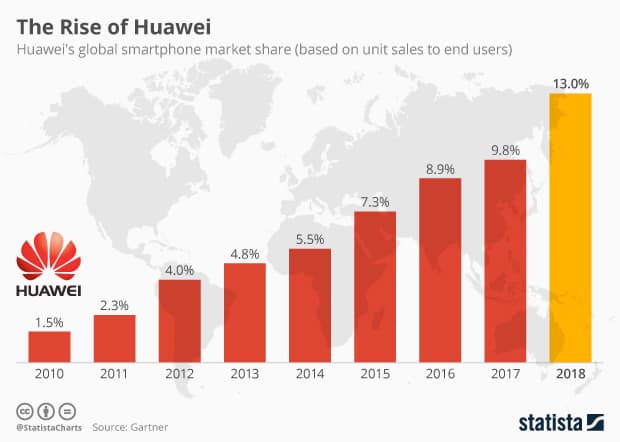

The Rise of Huawei globally, source: Gartner/Statista

Backdoors – are they there or not?

Of the entire supply chain attack surface, the most devastating attacks are hardware backdoors. Backdoor is a method of bypassing a device’s normal authentication or encryption.

Backdoors can be inserted anytime and remotely into Huawei devices. Attacker just needs to be on the same network to take control of the devices.

Cyber security forensic experts use a 1 to 10 scale to show risk associated with technical devices, where 1 is low risk and 10 is critical risk. “The critical risk means the control of the device can be fully taken over by attackers without the need of interaction with the device owner,” explains Pavol Luptak, cyber security expert from Nethemba, an IT security company.

Almost one third (27 percent) of security evaluations of Huawei devices had high or critical risk vulnerabilities.

Those high and critical vulnerabilities are caused by the very outdated and weak code used in the firmware, which is the code that controls the device. Backdoors providing full control of the device do not even need to be inserted by any special governmental forces or secret services: any skilled cyber criminal would be able to take over devices with these vulnerabilities. Hypothetically, cyber criminals could exploit this weak code in infrastructure projects such as nuclear power plants or air traffic control towers.

Additionally, as the Finite State report has shown, on average there were 102 known vulnerabilities (CVEs) associated with each piece of Huawei firmware tested. This indicates there are likely numerous ways to compromise a given device and turn it into whatever tool you need, from a listening device to a trigger for a detonator.

In April Vodafone Group Plc acknowledged to Bloomberg that it found vulnerabilities in Huawei devices, going back years, which could have given the Chinese company unauthorized access to the carrier’s fixed-line network in Italy, a system that provides internet service to millions of homes and businesses. In a statement to Bloomberg, Vodafone said it found vulnerabilities with the routers in Italy in 2011 and worked with Huawei to resolve the issues that year. There was no evidence of any data being compromised, it said. Some other vulnerabilities were also discovered.

Huawei has expressed its commitment to cyber security on many occasions, including through an over USD 2 billion investment in its improvement.

But promised improvements have still not happened. Instead, according to the report, Huawei developers continue to bypass security using very creative methods: such as including “security updates” that do not address security issues, continuing to use 10-year-old code known for its vulnerabilities, and new and more secure options or fixing unsafe functions by re-labelling them as “safe”.

In general, Huawei devices have substantially worse security than their competitors’ products.

“The Huawei device had substantially more known vulnerabilities and 2 – 8x more potential 0-day vulnerabilities then other comparable devices. Also Huawei device was the only device that contained hard coded default credentials and hard coded default cryptographic keys,” says Finite State’s report.

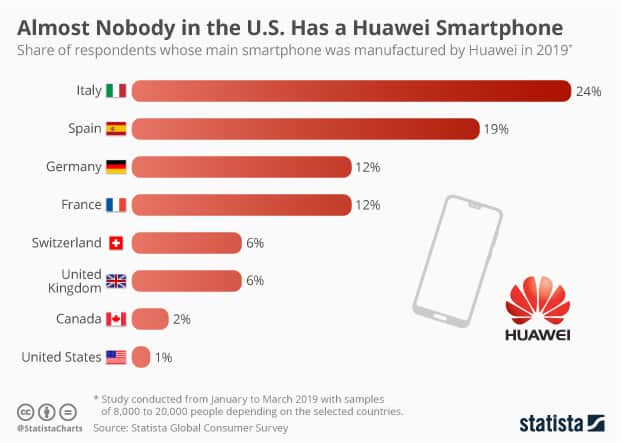

Huawei users, credit: Statista Global Consumer Survey

For all intents and purposes

The difference between a backdoor and a vulnerability is the question of intent. And intent is very difficult to prove.

The impact is the same, however.

The best intentional backdoors are designed to look like security oversights, so companies can claim deniability. Governments and secret service agencies making use of these flaws can also claim plausible deniability: They don’t need backdoors, they need the bad code. And of course, anyone else interested in exploiting the weak code could also easily do so.

In that sense, as the report indicates, national security, global trade, and international competitiveness are all potentially impacted. If companies supplying 5G technologies, such as Huawei, have secret or overt access to the infrastructure, “there is considerable concern that they could be persuaded to use access as leverage in times of peace, or perhaps something far more ominous in times of conflict,” says the Finite State’s study.

This is confirmed by Czech Cyber Security Unit (NUKIB): “The hardware and software of these companies [Huawei and ZTE] are cornerstones of information and communication systems that are or may be of strategic importance to national security. Violation of information security, ie violation of the availability, integrity or confidentiality of data in such information and communication systems, can have a major impact on the security of the Czech Republic and its interests.”

“Extended hand of the state apparatus”

How probable is it that Huawei will allow the Chinese government to use its products? According to the experts, very likely.

The Chinese National Intelligence Law of 2016 requires all companies “to support, provide assistance, and cooperate in national intelligence work.”

NUKIB mentions this as potential threat: “Legal and political environment of China, where those companies [Huawei and ZTE] are primarily operating and which laws they must respect, require the cooperation of private companies in pursuing the interests of China / including intelligence operations. […] There is concern the interest of China could be put above the interest of those technical devices users.”

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Huawei has categorically denied claims that it works with the Chinese government.

“Chinese law does not grant government the authority to compel telecommunications firms to install backdoors or listening devices, or engage in any behavior that might compromise the telecommunications equipment of other nations”, the company has said, further arguing that a lack of understanding of Chinese law should not be used as pretext for security concerns.

Technically, this statement is correct. Huawei does not need to install the backdoors itself, however experts say it can simply provide access to its devices to anybody who wants it – through installing updates, fixing bugs or other software activity.

“Chinese IT companies are an extended hand of the state apparatus. They are connected to the People´s Republic of China state institutions and fully support the Communist Party of China. The knowledge we have gained since the warning was issued (National Cyber and Information Security Agency issued a warning in December 2018 – VSquare), has confirmed this intention, ”explained Michal Thim, Strategic Information and Analysis Unit at the Czech National Cyber and Information Security Agency.

Warning by the Czech The National Cyber and Information Security Agency

“With the existence of this law, I cannot imagine a company that would have been asked by Chinese state to do a certain thing, the company would refuse it to do so. It doesn’t correspond to reality,” says Chinese expert Professor Olga Lomová, who works at Charles University in Prague.

Visegrad scaling

Even though Czech authorities claim they take the security warnings seriously, many of them continue to work with Huawei products. “We took security measurements like encryption of data, enhanced monitoring of devices, patch management of ICT infrastructure, change management of ICT structures or reaching out to different producers of the devices,” says the Czech Ministry of Interior.

In early January 2019, two men were arrested and charged in Poland with espionage on behalf of China: Piotr D. – a former Polish intelligence officer who had left the government to work as a manager at Orange, a mobile network company, and Wejing W., who was head of sales in Polish Huawei. They are each facing up to ten years in prison.

The arrests were a hard hit for Huawei, and according to unofficial sources the company is considering leaving Poland for Hungary if the case isn’t resolved soon.

Hungary, moreover, will welcome the company with open arms, as authorities there find Huawei a secure and reliable partner.

“The Hungarian government does not see any security risk in Huawei,” Gergely Gulyás, Minister of the Hungarian Prime Ministers office, said at his weekly press conference on 24 January 2019.

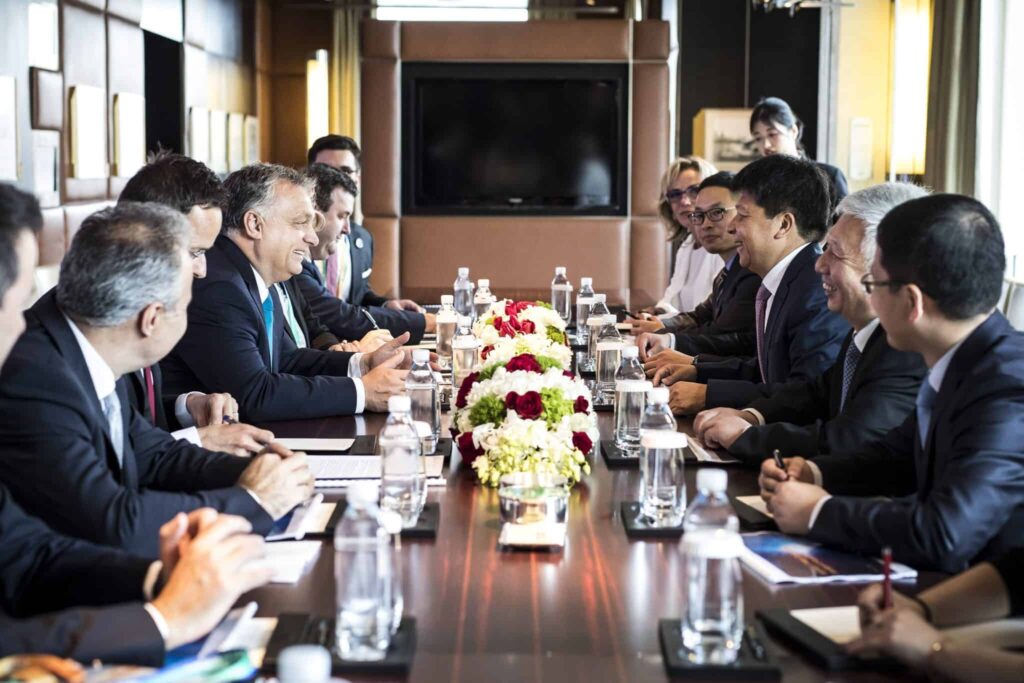

Hungarian government delegation in talks in Shanghai with Chairman of Huawei (Nov. 2018) | MTI/Miniszterelnöki Sajtóiroda/Szecsõdi Balázs

Ferenc Frész, former head of Cyber Defence at the Hungarian National Security Authority backed up the official statement when asked to comment: “The national security issue is not that we use breakthrough Chinese technology. The risk we run is that we do not have an established national research and development, and manufacturing potential. Looking further, there is not even an established European manufacturer, so all EU members are exposed to the same security risks. The only realistic question is whether European states should rely upon American, Chinese, or South Korean commercial service providers when developing their core communication networks,” Frész told Átlátszo.

This text was financially supported by GACC (The Global Anti-Corruption Consortium) aimed at the Visegrad countries. Member centers Átlátszo and Direkt36 from Hungary, Fundacja Reporterów from Poland, Ján Kuciak Investigative Center from Slovakia and investigace.cz from the Czech Republic are working on the project.

Co-founder and editor-in-chief at FRONTSTORY.PL, Wojciech Cieśla is an award-winning Polish journalist who, since 2016, has worked with Investigate Europe. He is the co-founder and chairman of Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He is based in Warsaw.

A Czech journalist, Pavla Holcová is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism. She is an editor at OCCRP and a member of ICIJ. She was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2023). Pavla is the winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award and, with her colleagues Arpád Soltész and Eva Kubániová, the World Justice Project’s Anthony Lewis Prize Award. She is based in Prague.

Hungarian journalist, works with the investigative outlet Atlatszo. She won the Junior Prima Prize in 2012. Former Fulbright/Humphrey Fellow. Based in Budapest.