Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY.pl)

Illustration: GoogleEarth.com 2026-02-05

Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY.pl)

Illustration: GoogleEarth.com 2026-02-05

The Russian sect known as the Anastasians promotes an anti-democratic, patriarchal ideology. For several years, its colonies have been quietly emerging across Poland.

We established that the movement in Poland was organized by a Putin sympathizer who bought land for his compounds for more than two million zlotys (roughly €460,000). Yet the authorities do not appear concerned — either about the group or its leader. That leader has since disappeared to Russia.

The Anastasian worldview is a cocktail of esotericism, conspiracy theories, ecology, racism, and antisemitism. In Germany, the movement is being investigated by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV). But what about in Poland?

Mikhail Gorbachev rules the Soviet Union. Russian troops are still stationed in Poland. And Vladimir — a skinny man in his thirties with a mustache — changes his surname to Megre. It is the mid-1980s.

Originally named Vladimir Luzhakov (or Vladimir Puzhakov, according to other sources), he lives in Novosibirsk. He has a wife and a daughter. He runs a small photography studio and, like almost everyone else, struggles to make ends meet. Like many, he senses that change is coming.

Before Gorbachev and communism fade into oblivion, the man now calling himself Vladimir Megre will reinvent himself as a businessman. He will set up one or two cooperatives and charter a couple of ships. His small “fleet” will travel thousands of miles along the Siberian Ob River. From these vessels, Megre and his men will trade whatever goods they can.

Then comes the turning point — at least, as Megre tells it.

In his book, he writes that in 1994, on the banks of a cold river near Surgut, in a place untouched by civilization, he meets a mysterious woman: Anastasia. A blonde in rubber boots with striking blue eyes. She takes him by the hand and leads him deep into the taiga.

There, she captivates him with a philosophy about humanity and nature — and the universe and God. She offers her views on lifestyle, education, nutrition, spirituality, love, family, sex, and even the purpose of plants. She shows him how to heal from a distance, and how to talk to squirrels.

Megre portrays himself as overwhelmed by Anastasia’s spiritual authority and her understanding of nature. Under the hermit’s influence, he changes his life.

Two years later, he publishes The Ringing Cedars of Russia — a book presented as truth and revelation, a testimony and a beacon for the lost. The hermit’s prophecies, written down for the world.

And there is serious money in revelation.

The book eventually sells 11 million copies worldwide, appears in 20 translations, and is released in two expanded editions. On top of that, Megre launches a line of eco-friendly products — a business he still operates from Novosibirsk today.

What may look like esoteric nonsense, profitable quackery, becomes the foundation of a new “ecological” movement: Anastasia. A movement that Vladimir Putin himself supports — and claims to understand.

The Siberian cedar becomes a sacred plant in this worldview: healthy, strong, aromatic. It is credited with special powers. Its nuts are said to calm the nerves and protect against magical attacks. The cedar supposedly repels mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas.

“Build a space of love on one hectare of land,” urges the taiga hermit in The Ringing Cedars. The book becomes the Anastasian bible — and a manual for anyone dreaming of escape from city life.

Today, at least several thousand believers in Anastasia’s forest prophecy live in several hundred one-hectare settlements across Europe. In their eyes, Siberian cedars are extraordinary. They heal disease. They radiate energy.

Whether Anastasia ever existed — or still exists — remains unknown. Yet Megre insists he still meets her regularly. In later volumes, filled with tangled wisdom, he continues to pass on her teachings.

Ancestral, Personal, and Compact

Self-sufficiency on one hectare: your own potatoes and tomatoes, as close to nature as possible — ideally within a multi-generational family. According to Megre, this is what the foundation of happiness should look like.

At the heart of the movement created by the Russian is the idea of the family homestead: a plot of land of at least one hectare that cannot be resold — only inherited. These family estates should then be grouped into “family villages.” Life there should be clean and harmonious, organized around the rhythms of nature, within a community of like-minded people. A life outside the system, shaped by natural cycles, and infused with elements of Slavic mythology.

And there is something else too — but more on that in a moment.

This movement, started by a businessman from Novosibirsk, has been described as “Russia’s ecological religion.”

According to the Russian website Anastasia, most of the more than 400 existing so-called “ancestral settlements” are located in Russia. There are large clusters in Belarus and Ukraine, and smaller, scattered ones in Poland, France, Spain, the United States, and Canada. During the pandemic, new settlements also began to take root in Austria and Germany.

Cheap land, few neighbors, and fields and forests in every direction — this is what much of West Pomerania looks like. Villages hidden among pine forests, where the Russian army was stationed just 30 years ago, may seem like the perfect place for a new beginning. Around a decade ago, a Pole named Piotr Kulikowski chose this region as the site for a colony of Russian settlers.

We know as much about Kulikowski as we do about Vladimir Megre — which is not much. From conversations with his friends and the few documents he left behind, we know that around 2015 he began promoting the idea of “ancestral estates.” Around that time, he purchased his first plots of land near Borne and Nowy Worowo in West Pomerania.

He then divided these several-hectare properties into smaller parcels — each one hectare in size — and sold them to several families from across Poland.

Buy a Hectare, Grow Potatoes

Polish Family Estates draw on the “wisdom” of The Ringing Cedars of Russia. “Family” and “cedar” are key slogans in the Polish version of the movement. Some members are active on social media. What they post and say is mostly a muddled cocktail of New Age rhetoric — meant to suggest that growing tomatoes and onions on your own hectare is not only relaxing and idyllic, but can also change the fate of the grower, and even the world.

According to land registry records, Piotr Kulikowski was — or still is — the owner or co-owner of at least 78 hectares in Poland’s West Pomeranian Province. He purchased the land between 2015 and 2022 and sold it between 2017 and 2025. Based on county real estate price registers and land registry documents, we established that he spent at least PLN 2.3 million (approx. EUR 535,000) on these purchases. Where did he get such sums? How did he support himself during that time? We have not been able to determine this.

On the land he acquired, Kulikowski established two Anastasian compounds: Aleje Cedrowe and Kwitnące Ogrody. Today, they include a total of several one-hectare farms.

The 47-year-old Kulikowski comes from Łuków and worked in West Pomerania for several years. According to our sources, like Megre, he changed his surname — adopting his grandmother’s. What does he do for a living? It is not known.

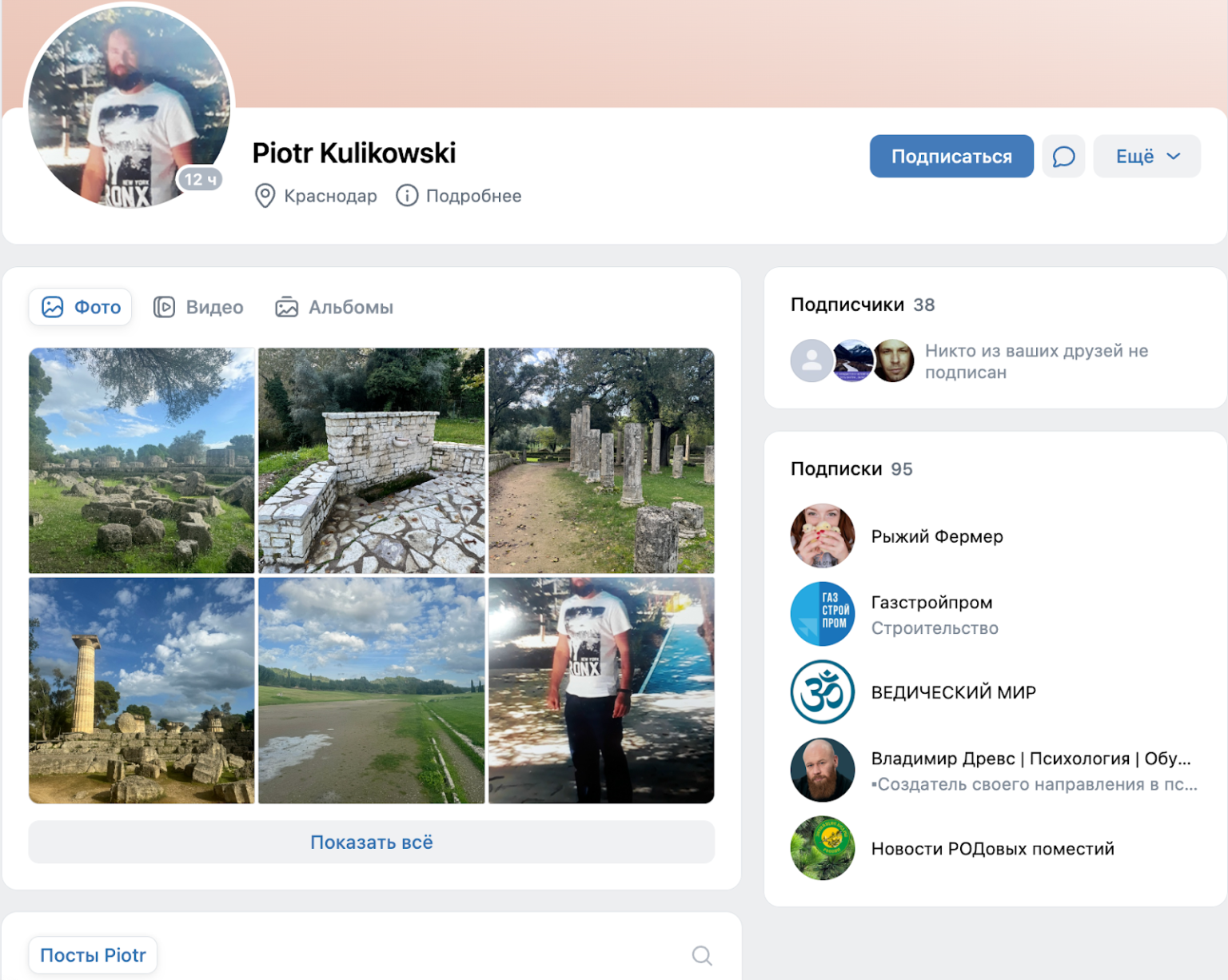

Today, there is no way to contact him: he has disappeared. People from his circle whom we spoke to do not know where he is. His profile on the Russian social network VKontakte suggests he is in the Russian Federation, where he last showed activity. The most recent photos he posted are from Russian-occupied Crimea (Sevastopol), Dzhubga (Russia), and Olympia (Greece).

The people who helped him start Cedry remained in Poland. One of them is Tomasz Ozdowski, who bought his Anastasian hectare from Kulikowski. Ozdowski describes himself as a neuro-linguistic programming coach and a health prevention enthusiast. He is a missionary of the movement, active online, recording videos filled with cult-like “wisdom” (for example: why are family plots separated by a 1.5-meter border? So that the energies of different family lineages do not mix).

Ozdowski described buying a plot in Kwitnące Ogrody (the name of one of the compounds) like this:

“[Piotr] walked us around these 18.5 hectares, because that’s roughly how much our settlement here covers in total. And we, in our half-boots, with snow almost up to our knees, started jumping in his footsteps, following him. And the whole story ends more or less like this: after about two hours and a few exchanges, we decided yes — we wanted this land. Piotr then said: ‘This is going to be a settlement inspired by Vladimir Megre’s books The Ringing Cedars of Russia. Have you read them?’ He asked all future residents this question.”

Low Profile — And an Interview with Putin

Kulikowski told those interested in his plots that he was building a settlement inspired by Megre’s books. He asked potential buyers whether they were familiar with The Ringing Cedars.

Today, Kwitnące Ogrody consists of 14 plots, some of them uninhabited. Owners communicate via the Russian messaging app Telegram, and at least once a month they hold a so-called “compound meeting,” where they discuss issues related to the shared common area (around three hectares).

How did Kulikowski gather people to build the settlement? One of his friends describes it like this: “He has something about him that makes people gravitate towards him and get involved in creating these settlements. Each of us has qualities that we bring to this community, so it all comes together nicely.”

Members of the movement also set up two “Polish” news sites online: Kwartalnik Rodowa Posiadłość (Quarterly Family Estate), edited by Tomasz Ozdowski (its last issue was planned for July 2025), and Monika Nawrocka’s website polskierodoweposiadlosci.pl (the domain is currently for sale). According to both sources, several dozen people inspired by The Ringing Cedars live in Anastasian settlements in Poland.

Kulikowski says these people keep a “low profile” — they act discreetly and avoid publicity. They limit their activity and visibility, do not appear in public, and stay away from social media.

Kulikowski rarely appears on Polish social media. But on Russian channels — Telegram and VKontakte — he presents a different image. He lists Krasnodar, Russia as his place of residence. He frequently shares pro-Russian content: interviews with Putin, as well as posts encouraging support for the Russian economy through travel or investments in cryptocurrencies.

Kulikowski’s profile on vKontakte, Source: vKontakte

The content he shares includes a video by Joseph Stephen Rose, an American who moved to Russia in 2022, the year of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, to help immigrants from the West settle in the country. According to him, the US is moving away from traditional family values, which, in his opinion, is harmful to children. Kulikowski also shares a link to an interview with Vladimir Putin by pro-Russian commentator Tucker Carlson.

The account of the Western Association of Entrepreneurs (a fictitious organization invented by Kulikowski, but more on that in a moment) on the Russian platform vKontakte has a lot to say about self-sufficiency — infrared films, renewable energy sources, and owning a piece of land.

Let’s Make a Law — Just Like in Russia

Kulikowski appears in Borne and Nowy Worów a year after the annexation of Crimea, in 2015. At the time, Russia’s State Duma is already preparing a major campaign: allocating hectares of land to families willing to live as if on “ancestral estates.”

This is also the moment when Anastasianism is, in practice, blessed and legitimized by the Russian state. Why?

In 2012, the Rodnaya Party (“Native Party”) was founded in Russia. Its key demands came straight from Megre’s books — above all, the right of every family to its own “ancestral” hectare, along with an ecological policy rooted in Russian culture and agriculture. This was no coincidence: the party was led by people linked to Megre, and launching a new political party was his idea.

A year later, a bill on ancestral homesteads was submitted to the Duma — but then shelved. The issue only resurfaced, and escalated, in 2015, when Vladimir Putin himself embraced the concept of one-hectare homesteads. The Kremlin leader had his own version of the plan: he ordered the development of a program to allocate one hectare of land for free to every resident of Russia’s Far East, and to anyone willing to relocate there. Under the program, foreigners are not eligible for such plots.

Putin signed the bill on May 1, 2016. The authorities then began distributing one-hectare plots in the Far East to anyone interested. Where did the idea come from? Russia’s eastern borderlands are a demographic desert. The Far Eastern Federal District includes 11 regions, all of them steadily losing population.

In 2020, Russia’s Supreme Court dissolved the Rodnaya Party for inactivity; today, there is no trace of it. The party never became a significant political force, operating mainly at the local level. But the idea of a political movement for “one-hectare owners” sprouted abroad — specifically in Poland, in the mind of Piotr Kulikowski, a self-declared admirer of Putin.

In 2021, in the Anastasian settlement of Blooming Gardens (though no organization under this name is formally registered), the West Pomeranian Association of Ancestral Estate Entrepreneurs was founded as an “informal forum for exchanging experiences.” It is not registered either, but on VKontakte it promotes ideas about “building broadly understood financial and food self-sufficiency.”

There, Kulikowski outlined his original vision for a Family Party. Its representatives could belong to different political parties, but their shared goal would be to push for “the adoption and subsequent implementation of the Family Estates Act.”

Kulikowski devoted substantial space to this draft Polish law — clearly inspired by the Russian model — in his online quarterly magazine. But the proposal never made it to the Sejm in any form. The quarterly itself eventually came under the editorship of Tomasz Ozdowski, who, after settling in one of the compounds, increasingly turned into a missionary for the idea.

Comrade Shchetinin Promotes the Kolkhoz

We are going to visit the Polish Family Estates in Borne, Kiełpin, and Nowy Worów.

In Kiełpin, the first construction works are already underway by a private lake — accessible only to members of the community.

Residents say that what used to be a relatively uniform community has recently fractured. One faction is Kraina in Kiełpin, led by Tomasz Czapski. Another has split into two smaller groups, both of which in the past were linked to Kulikowski.

Kraina resembles a hippie commune. Visitors can buy handicrafts and stay overnight for fifty złoty. On the way to the next compound, in Borne, we meet one of the residents — Ola (name changed). What does she think about Kraina, and how does it differ from her community in Borne?

Ola says Megre’s books were one of the things that inspired her to join the settlement. We talk about buying land, and it quickly becomes clear that membership comes with conditions: to be accepted, you need to have children. There are already too many single women, she says, and there is no room for more singles — or even couples without children.

One resident tells us that “children are the most important resource, because the idea has to be instilled in them.” The community runs its own “school,” where the youngest learn about the world according to the vision of the hermit Anastasia. (Residents insist the children attend normal state school as required, and come here afterwards.) Anastasians call it the School of Happiness. They proudly add that their children are taught using the Shchetinin method.

This brings us to another key figure in the story: Mikhail Petrovich Shchetinin, a Russian educator whose career was shaped by the turbulent post-Soviet years. In the 1980s, while working as a senior employee at a research institute under the USSR Academy of Pedagogical Sciences, Shchetinin developed the idea of creating small “school collective farms” — institutions combining education with labor. The experiment collapsed and was shut down by the USSR Ministry of Education. But in the early 1990s, Shchetinin revived it in a village in Krasnodar Krai. He, too, became a follower of Vladimir Megre’s teachings (Shchetinin died in 2019). His students lived in an isolated commune, cut off from the outside world. They had no private space and virtually no free time.

Not everyone in Borne is comfortable with the Anastasians. Some local residents dislike the closed nature of the community, and tensions have been growing. They claim Kulikowski bought the land for next to nothing from a local farmer. They also claim that Ozdowski — the editor of the Rodowe Posiadłości newspaper—liked to boast about his ability to “change consciousness.”

We try to contact Kulikowski, but without success.

Grow a Beard, Don’t Provoke Desire

People who bought plots among the Anastasians talk about it online—among them Katarzyna Świstelnicka and Magdalena Okoniewska-Marczak, who are active in groups promoting permaculture gardening and “life outside the system.”

Some, like Tomasz Ozdowski, actively promote the idea of Ancestral Settlements on social media. The movement is led by Tetiana Dombrowska, who is also friends with Kulikowski on the Russian social network VKontakte.

Online, the community appears harmless—new age, peaceful, almost naïve. But on the profiles of Kulikowski, who helped create the community, and on the website of his West Pomeranian Association of Entrepreneurs, we find explicitly political, pro-Russian content. This includes interviews with Putin and materials meant to offer a “different perspective” on the war in Ukraine—meaning, in practice, a pro-Russian one.

The Anastasians are not only active online. They also organize real-life gatherings. Events linked to Cedry take place all over Poland. One description—advertising a meeting of Megre’s book fans in July 2024 in Siennów, in the Podkarpacie region—includes the following invitation:

“(…) There will be dancing, but women and men will dance separately. Women should wear dresses without a large neckline so as not to provoke sexual attraction in men.”

Men, meanwhile, are encouraged to “start growing beards and hair.”

Researchers studying sects at the universities of Graz and Munich have identified antisemitic, nationalist, and xenophobic themes in Megre’s books. This is because beyond naïve esotericism and an ecological veneer, The Ringing Cedars of Russia promotes serious and dangerous ideas: hostility toward modern society, conspiratorial thinking, and aversion to minorities. The movement rejects human rights and democracy. In the worldview of its Russian founder, people are manipulated by governments—especially Western ones—and by the media, and must “wake up” to a new life. Salvation, in this vision, will come from Russia.

In Anastasia’s prophecies, all-powerful Jews possess immense wealth and influence over governments around the world. A return to nature is framed as a return to racial purity. One passage from the Cedars series, devoted to Jews, states:

“They try to take at least something from someone who is not very rich, and they strive for the complete ruin of the rich. This is confirmed by the fact that many Jews are rich and can even influence the government” (Anastasia, vol. 6, p. 174).

Esotericism with a Small Mustache

During the pandemic, a toxic mix of esotericism, conspiracy theories, ecology, racism, and antisemitism flourished in Austria and Germany—although it had been present in both countries for at least a decade before that.

In Germany, the movement has been active since 2011, but it truly took off in 2014. Its members set up family farms in remote areas and try to live off the land. They believe that a close connection with nature will give them extraordinary abilities, such as teleportation and telepathy.

According to German media, more than 20 such projects were operating in Germany in 2022. The largest, “Goldenes Grabow,” is located in Ostprignitz-Ruppin in Brandenburg and is run by Marcus and Iris Krause. Another community is Weda Elysia, led by Maik Schulz.

In Germany, the movement publishes a newspaper titled Garten Weden, and many of its members are linked to the AfD, the pro-Russian far-right party.

In Austria, the key figure is anti-vaccination activist Norman Kosin, who moved with his family from Sylt to a secluded estate in southern Burgenland. He is extremely active on Russian Telegram. He uses “Anastasia channels”—each with around 250,000 subscribers—to spread anti-vaccination and antisemitic propaganda. New recruits are drawn in through the same ecosystem.

According to the Austrian Documentation Center for Religiously Motivated Political Extremism, the movement should be classified as a dangerous sect. Ulrike Schiesser of the Federal Advisory Center on Sects also drew attention to the Anastasia movement in a 2022 report, pointing to “anti-democratic tendencies that should be monitored.”

Germany’s Office for the Protection of the Constitution likewise considers the movement an extremist organization acting “against the free democratic order.” Megre’s books have been classified as “incompatible with the principles of democracy and human dignity enshrined in the Basic Law (German Constitution).”

The Office for the Protection of the Constitution is currently monitoring five Anastasian farms in Brandenburg.

Are Polish security services monitoring the pro-Putin Anastasia movement as well? We asked the Internal Security Agency (ABW) and the services’ spokesperson, Jacek Dobrzyński, about this. His cautious response suggests this may not necessarily be the case:

“We would like to inform you that the Internal Security Agency is constantly monitoring events, places, organizations, and individuals that may pose a potential threat to the security of the Republic of Poland. However, information on identified threats is only disclosed to the competent government authorities, in accordance with the procedures and rules laid down in the applicable regulations.”

The Polish version of this investigation was published on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Daniel Flis previously was on the investigative team of OKO.press and Gazeta Wyborcza. OCCRP Research Fellowship Program recipient. Participant in international investigative projects of the Reporters Foundation.