Photo: Globsec Media Kit 2025-07-18

Photo: Globsec Media Kit 2025-07-18

The GLOBSEC Trends 2025 report analyzes public attitudes across Central and Eastern Europe on topics such as security, perceived internal and external threats, and trust in media, government institutions, and NGOs. The findings are based on nationally representative surveys conducted between February and March 2025. Countries included in the report are Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

Katarína Klingová, a senior research fellow at the Center for Democracy & Resilience at the GLOBSEC Policy Institute, spoke to VSquare about the GLOBSEC Trends 2025 report, which she co-authored. Katarína previously worked with Transparency International Slovakia and the European Commission. We highlighted key cross-border trends in the V4 region, along with specific issues that Katarína explored in greater depth.

Source: Archive of Katarína Klingová

Earlier this year, an international investigation, including Hungary’s Direkt36, covered how China silences its critics abroad. How would you evaluate the perception of influence activities by China and their prime (trade) rival, the United States in Central Europe?

When we look at the United States and China, 40% of Central Eastern Europeans see the United States as their country’s most important strategic partner. There are, of course, significant differences between countries—Polish respondents, for example, overwhelmingly name the U.S. as their top partner, which has historically been the case and is unlikely to change.

However, when looking at the broader region, Germany emerges as the most important strategic partner, cited by 49% of respondents. This is largely due to the deep economic interconnectedness between Germany and the Central European economies.

As for China, only 11% of respondents view it as their most important strategic partner. China is not seen as a traditional partner of the region, and it is not a part of the EU and NATO, which are viewed as the key pillars of both economic and defense cooperation.

When it comes to perceptions of security threats, only 34% of respondents currently view China as a threat, compared to over 60% who see Russia as a security threat. For obvious reasons, perceptions of Russia as a security threat increased significantly in some countries—such as Slovakia—after the full-scale invasion.

In Slovakia, for example, the percentage of respondents who viewed Russia as a threat rose from 20% (2020) to 62% (2022). However, that number has since dropped, and now only 50% perceive Russia as a security threat.

We conducted focus group discussions on China several years ago, and I believe the findings still hold. When we asked participants why they do or do not see China or Russia as security threats, the common response regarding China was: “We’re far away, we’re not interesting to them, we’re small.”

There was an investigation into a Chinese cyberattack in the Czech Republic. For the first time, the Czech government directly attributed such an attack to the Chinese government as a state actor. Do you think such singular events can shift perceptions of China as a security threat—particularly in the Czech Republic?

I think so. In fact, Czechia is the only country where a majority of respondents perceive China as a security threat.

I believe this is due to the openness of the country’s political leadership. There is strong political support for Taiwan in Czechia. On several occasions, Czech political representatives were directly threatened by the Chinese government not to visit Taiwan—and they chose to stand firm. Czech intelligence services are also very transparent and regularly publish reports mapping out Chinese influence operations or attempts to exert influence within the country. All of this contributes to heightened public awareness and concern.

On the other hand, you have countries like Hungary or Slovakia, where political leaders frequently travel to China, and Chinese officials visit these countries to sign major economic agreements. There was even an agreement to allow Chinese police to patrol in Budapest.

Chinese police presence and unofficial “police stations” exist around the world, including in many European countries. The key question is whether they are visible or not. Just because they aren’t visible doesn’t mean they aren’t influential. These operations aim to shape democratic discourse about China, suppress opposition voices, and influence public debate—especially in universities. That’s precisely why Confucius Institutes were also established.

Source: Globsec Media Kit

Besides influence and partnerships with China and the United States, the region is also grappling with its own rule-of-law challenges…

Hungary and Slovakia have recently seen a trend of anti-NGO legislation. In Hungary, at the moment the “foreign agent law” has been postponed until fall. In Hungary, the proposed law would allow the government to blacklist organizations receiving any foreign funding and restrict their operations. In Slovakia, a similar NGO law was passed—but only after significant changes to the original draft, which may have violated European Union law. After the amendment, every donor above €5,000 per year has to be disclosed.

In Slovakia, the law that was passed imposes more of an administrative burden than a real threat—especially compared to the original draft, which was far more problematic and closely resembled a foreign agent law.

Do you think the situation will evolve similarly in Hungary and Slovakia, and how will civil society respond?

Civil society is a key pillar of resilience in every country. When we’re facing various malign activities—whether from domestic or foreign actors, often of a hybrid nature—only a whole-of-society approach (involving cooperation between the public, private, and civil sectors) can lead to a more resilient and self-sustaining society.

In many countries, civil society organizations have stepped in to supplement or even replace state efforts in building resilience—this is true in places like Slovakia, and also in Hungary.

In Slovakia, civil society plays a particularly active role. Many organizations provide media literacy training, analyze hybrid threats, or conduct public opinion research to improve societal awareness and understanding of emerging threats.

Attacks on civil society aren’t new. Smear campaigns have been ongoing for years—labeling civil society organizations and independent journalists as “foreign agents” has become a common tactic. It’s politically convenient to invent an imaginary enemy and blame them for everything.

Last year, we asked people whether they believed civil society organizations were foreign agents. In some countries—Hungary, Bulgaria, and Slovakia—around 35% of the population said yes. But in this year’s survey, when asked whether their country should do more to support civil society organizations, 79% of Hungarians agreed. After more than a decade of attacks on civil society, independent media, and journalists, the Hungarian public seems to have become desensitized to these narratives. Many simply don’t buy into them anymore.

Of course, these narratives are often populist in nature. It’s politically convenient to invent an imaginary enemy and blame them for everything.

As for legislation, we’ll see how things develop in Hungary. In Slovakia, the law that was passed imposes more of an administrative burden than a real threat—especially compared to the original draft, which was far more problematic and closely resembled a foreign agent law.

In Slovakia, we clearly see that the public is willing to support institutions, initiatives, and the work of civil society organizations. A powerful example was the widespread support for the formerly persecuted police officers around Ján Čurilla, who had been investigating high-level corruption. That campaign alone raised more than €300,000 to assist them.

We’ve also seen inspiring initiatives like 365tka, launched by journalists who were being censored at Slovakia’s largest private TV, Markíza. Now, even more journalists are leaving or being fired from the channel. Within a week of launching 365tka, nearly €600,000 was raised through public support.

So, the willingness and capacity to act are clearly there. Yes, polarization exists in many countries, but when people truly understand a cause, they are ready to support it. When they see the ongoing mismanagement of public funds and the endless stream of corruption scandals—new ones emerging almost every week—they are motivated to back those who expose the wrongdoing and drive real impact.

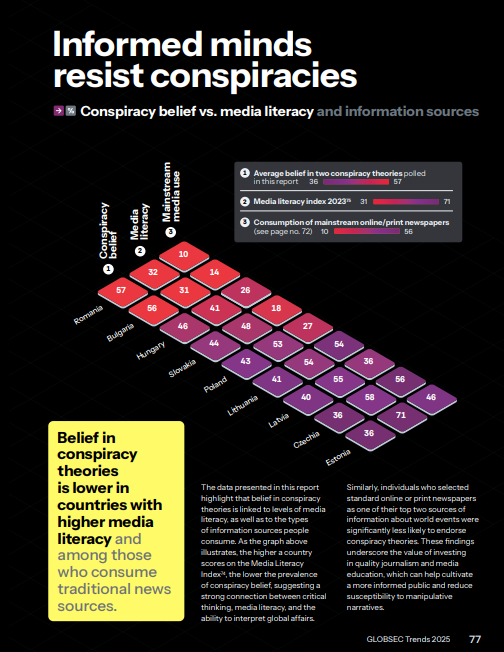

The GLOBSEC Trends 2025 report shows the Czech Republic performing notably well in trust in traditional media, with 57% of respondents expressing confidence—placing it among the most media-trusting countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Czechs also showed the lowest belief in conspiracy theories, with only 32% agreeing that the world is controlled by secret groups. Moreover, it was the only country where more than half of respondents viewed both Russia and China as security threats. What do you think explains this phenomenon? Is it better education or stronger preventive measures?

Source: Globsec Report 2025, p. 77

The education system in the Czech Republic is certainly strong—better, for example, than Slovakia’s. In Slovakia, we’ve been discussing education reform for over a decade, but very little has actually been done. Of course, every country faces challenges, but if we compare the public broadcasters in Czechia and Slovakia, the contrast is stark. Czechia’s public broadcaster, Česká Televize, is an institution in its own right.

While there have been some attempts to interfere or capture the broadcaster, Česká Televize continues to produce quality journalism and investigations.

In contrast, Slovakia’s public broadcaster has suffered from clear signs of state capture. Many experienced journalists have left over the years, and at one point, the director was working on a deal for the Slovak News Agency (TASR) to exchange content with [Russian] Sputnik News, which was canceled right after it came to light due to public backlash.

All of this affects what we might call situational awareness. In Czechia, Česká Televize remains a primary source of reliable information—both domestic and international—which directly contributes to higher media literacy and a lower tendency to believe in conspiracy theories. It’s all interconnected.

You also don’t see as many political figures in Czechia openly attacking investigative journalists. There have been some efforts to capture media institutions, and we’ll see how things develop after the Czech elections in October 2025. Yes, Andrej Babiš still owns a significant portion of the media landscape—but the independence of Česká Televize and major investigative outlets has largely held up and remains strong.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Tamara is a journalist from Slovakia, currently based in the Netherlands. Besides VSquare, she writes for The European Correspondent.