Mindaugas Aušras (LRT)

Szabolcs Panyi (Vsquare.org) 2023-10-26

Mindaugas Aušras (LRT)

Szabolcs Panyi (Vsquare.org) 2023-10-26

All they wanted was fast cash, but what they got were prison terms. In recent years, the number of Lithuanians and Latvians arrested for illegally transporting migrants has risen sharply. This trend is not expected to slow down. It also doesn’t help that some transit countries, such as Hungary and Poland, let them get away with it.

As dusk settled one October night, Alexander, a Latvian high school student, drove his cargo van into a forest near the Hungarian-Austrian border. The evening was chilly, but he didn’t feel it. He stayed in the vehicle with the lights off, as instructed.

He soon noticed people approaching. They quickly filled the van’s cargo area, and some joined him in the front seats. Then came a knock on the cargo area wall. Everyone was ready to go, and Alexander started his drive to Austria. Unbeknownst to him, this journey would lead to death for some passengers and imprisonment for him. He had unwittingly become part of a highly profitable crime network involved in transporting undocumented immigrants.

Alexander’s story isn’t unique. The involvement of Baltic nationals in such activities has become a significant problem. In 2022, the Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs publicly warned against accepting suspicious chauffeur job offers, highlighting the growing concern in the region.

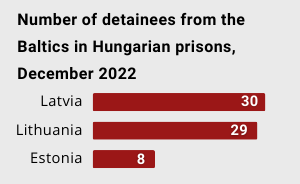

The number of Baltic nationals detained abroad shows that the situation has become “alarming,” especially in Hungary, where law enforcement officials detain Latvians and Lithuanians on trafficking charges once or twice weekly.

Since 2021, just over 30 Latvian drivers have been detained in Hungary, as have 31 from Lithuania.

“I’ll tell it like it is, it’s quite a lot for Latvia,” concludes Agnese Kalniņa, the Latvian ambassador to Hungary, in an interview with Re:Baltica.

Vytautas Pinkus, the former Lithuanian Ambassador to Hungary, attributes the high Baltic involvement in trafficking to the active recruitment efforts of criminal groups in the Baltics.

The scheme is simple.

Drivers are found on social media or through friends for transport jobs in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Poland, and Serbia.

These are the countries through which migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Turkey, and elsewhere cross when taking the Balkan route in search of a better and safer life in Germany.

From the Baltic states, men from Lithuania and Latvia responded most frequently to these job posts and offers. Ranging in age from 20 to 45, they had varied educational and social backgrounds.

Alexander was just 19 when he took such a job. A final-year secondary school student from a small Latvian town, he had hoped to become a photographer. Then he came to face seven years in an Austrian prison.

*

Why did he take the job?

“They promised mountains of gold” is Alexander’s response.

A good friend offered him the chance to earn several thousand euros in just one day’s work. He wouldn’t even miss much school.

Alexander only found out who, exactly, his passengers were after arriving in Austria. This is one of the recruiters’ strategies: hire people only to reveal the true picture later.

Among other things, recruiters tell the drivers that even if the police catch them, there will be no punishment because they are foreigners. Or, the migrants will only have to be transported within the borders of one country, which is not a crime.

These are all lies.

At Vienna International Airport, Alexander met the coordinator, who gave him instructions. He picked up the already-fueled van at a nearby petrol station and began the four-hour journey to the Hungarian border.

The coordinator sent the route on the phone and stayed in contact the whole time.

The return journey proved disastrous for Alexander. It took twice as long as the first leg, as the organizers directed him on detours to avoid getting caught. As a result, the van crossed the Austrian border after almost nine hours.

He had been driving in Austria for only a few minutes, on a remote country road near Eisenstadt, when the van was stopped by police.

Alexander fled.

He leaped from the van, sprinting through bushes and across a meadow. Once he realized he had escaped, he returned across the Hungarian border and contacted the coordinator. After some time, he was picked up and transported through another border crossing to a residence in Austria. The apartment, which had several rooms and numerous folding beds, served as a temporary abode. Despite not completing the job, Alexander still received payment and flew home.

Two months later, while heading to work after school, he was apprehended by the police. Two weeks after that, he was deported to Austria.

It was in a Latvian police cell that he discovered that two of the 29 migrants he had been transporting didn’t survive the journey. When the police opened the vehicle doors, they found the two men had suffocated to death.

Subsequent reports from Austrian media revealed that the men inside had run out of oxygen in just a few hours. In despair, they tore at the insulating rubber near the doors to allow some air in. They pounded on the walls, shouting, “Dying in here, stop!”

They had no drinking water after spending the previous three days in the forest. The initial plan had been to transport the migrants in two vans, but for some reason, everyone was squeezed into one, akin to “sardines in a can.”

“There was a prevailing fear of death within the vehicle,” emphasized the prosecutor during the trial.

Alexander heard the screams but continued driving, following the coordinator’s instructions.

“It was a shock,” Alexander remembers his feelings upon learning about the deaths. “And a disappointment. That it occurred because of me. Due to my irresponsibility.”

*

Hungary has become a hotspot for the detention of Baltic nationals, as its prime minister, the far-right populist Viktor Orbán, has made the fight against migrants a cornerstone of his policy.

“We are not only protecting Hungary from illegal immigrants, but we are protecting the whole of Europe,” Orbán declared at an event in Vienna this year.

Hungarian border guards stopped 330,000 migrants from entering the country last year, the Hungarian government claims.

That’s the rhetoric. But the reality is something different.

Hungary has been in an economic crisis for years. Police are seriously understaffed, underpaid, and underequipped. They are visibly unable to crack down on illegal migration. Both undocumented immigrants and their traffickers still have quite a good chance of crossing the country.

By the end of August 2023, just before Slovakia’s parliamentary elections, a state of emergency was declared in parts of Slovakia due to the more than 24,000 migrants who were crossing en masse from neighboring Hungary. At least two of them were identified as terrorists by Slovak police.

Last year, however, the Hungarian police, in cooperation with colleagues in Austria and Serbia, were still making somewhat of an increased effort to catch those transporting migrants, detaining around 2,000 people in total, Hungarian police data shows.

Penalties in Hungary are harsh, with sentences ranging from two to eight years in prison. In contrast, Latvia and Lithuania typically hand out fines and/or community service for similar offenses. However, this year, as the number of drivers caught has increased, penalties in Latvia have become stricter.

Among those detained in Hungary was Tom, a father of two young children from Jurmala, a well-known resort town in Latvia.

Tom worked as a long-haul driver, transporting belongings for Latvians living abroad, but his income was irregular. Last autumn, he came across a job offer for a driver on Telegram. He reached out, and a man who called himself Emils, likely not his real name, responded.

They started communicating on another platform, Signal and met once, after which Emils provided money to rent a cargo van.

The next day, Tom was heading to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia.

Tom was led to believe his job was to transport migrants solely within the confines of Austria, implying that nothing illegal was involved.

In Bratislava, Tom received directions to head to Budapest, Hungary’s capital, and then to Kecskemét, halfway to the Serbian border.

He picked up several migrants from the highway that night. He didn’t know how many exactly as it was dark, and he didn’t count.

On his return trip to a town near the Austrian border, the police stopped him. It seemed they were expecting him, as all the highway exits at that location were blocked. Tom stepped out of the van. Two officers held guns to his head while another handcuffed him and made him sit on the ground.

“I never want to experience something like that again,” Toms told Re:Baltica.

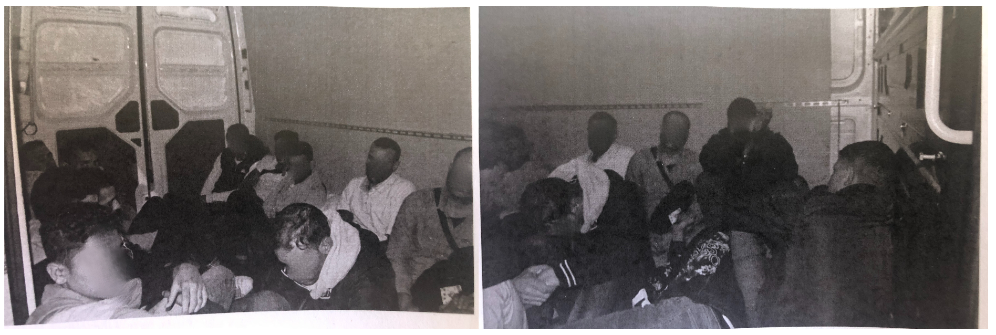

When Hungarian police opened the doors of the van driven by Toms, they found 15 migrants sitting on the floor. Source: Materials from the criminal case files.

When they opened the van’s cargo compartment, they found 15 Syrians sitting on the floor.

“Mom, mom, hi, listen, I’m stuck in Hungary. I’m in jail. I’ve been here for six days now,” was the first voice message Tom sent to his mom, asking her to get him a lawyer.

But it was no use. Lawyers in Hungary were asking between 4,000 to 12,000 euros. His family didn’t have that kind of money. So Tom was assigned a state-paid defender by Hungary.

The court couldn’t provide a Latvian translator, so everything was translated into English, which Tom only somewhat understood.

He was sentenced to five years in prison.

Tom was beginning to come to terms with spending years in a cell with five other people, but something unexpected happened.

“Hi, mom, they’re letting me out tomorrow at ten,” he called his mom in Latvia this March.

One in ten inmates in Hungarian prisons last year was serving a sentence for transporting migrants. Most of them were foreign drivers.

Source: helsinki.hu

Then, early this year and seemingly out of the blue, Hungary started releasing convicted inmates. The country was struggling to meet the European Union’s standards for inmate living conditions and cited the high costs of detaining foreigners to justify the move.

“It’s called ‘reintegration custody.’ The prison management decides to release an inmate, and then they have to leave Hungary within 72 hours,” explains Agnese Kalniņa, Latvia’s ambassador to Hungary.

“Okay, I’m coming to get you,” Tom’s mom replied in a phone call.

A few hours later, she hopped into her old Volvo and started the 1,500-kilometer drive from Jurmala to Hungary. She picked up Tom the next day as he waited by the highway near the prison in Szombathely.

According to the Latvian embassy in Hungary, by mid-summer, three Latvians had been released under this new rule, while nine were still waiting in prison.

The Lithuanian embassy estimates that around 20-30 inmates from Lithuania might have been released. It’s hard to get an exact number because Hungarian prisons don’t usually inform other countries’ embassies.

“We have released 1,468 detainees of foreign nationality who have been convicted of smuggling of human beings,” Hungary’s penitentiary services told AFP in late August. The unilateral move drew anger from Austria and many other EU countries as Hungarian authorities don’t actually follow what happens to the traffickers once they’re released.

*

The death of two immigrants in the van driven by Alexander, the high school student, in October 2021 resonated loudly in the Austrian media. As a result, law enforcement intensified their focus on the case and apprehended the organizers. This is a rare exception, as the less significant drivers are usually caught while the organizers escape unscathed.

In Alexander’s case, an Austrian court convicted a group of 20 individuals. They were primarily young men from Romania and Moldova. Over three months, they had brought around 350 migrants, mostly from Arab countries, into Austria, earning a total of 1.7 million euros. Each migrant paid around 5,000 euros.

The death of two immigrants in the van driven by high school student Alexander caused a significant uproar in Austrian media. Source: Picture-alliance/AP/Robert Jaeger; APA

Interviews conducted as part of this investigation, both with drivers in Hungarian prisons and with those who have been released, reveal that the payment for transportation varies from a few hundred to thousands of euros. The number of people transported is also crucial, as there could be an additional bonus for each immigrant.

Re:Baltica confirmed this as well. Earlier in the spring, a journalist from Re:Baltica responded to a driver job advertisement on Facebook in a Hungarian job seekers group.

An anonymous account responded in Russian and explained that, for our case, we would have to transport migrants from the Latvia-Belarus border to Germany. The payment would be 900 dollars per person, with the number of passengers depending on the vehicle size. Coordinates for picking up and dropping off the migrants would be sent as GPS coordinates shortly beforehand. To reduce the risk of being caught, the anonymous account suggested sending another vehicle ahead to scout for police on the road.

Re:Baltica inquired about the job offer from a young woman’s Facebook profile, and there were no issues with that. Initially, the anonymous person who offered the job mentioned that the “job was somewhat on the shady side” and probably wouldn’t be “suitable” for a young woman. However, they later explained the conditions.

While it’s less common, women also consider offers for driver positions. One of these women was a Latvian, Madara (35), who had found herself in financial trouble. Last September, a friend offered her the opportunity to earn 1500 euros by transporting migrants to Germany, and she agreed. She boarded a bus arranged by the organizer, and once in Lithuania, in a forest near the Belarusian border, she took in 10 migrants. They were apprehended in Poland, and Madara spent three months in detention. According to her, the case was eventually closed, and she was released. She was the only Latvian in the prison; the others in her cell were mostly Lithuanians and Ukrainians who had accompanied their boyfriends working as drivers.

“As we joked among ourselves – every other person was detained for ‘tourist transportation,'” Madara tells Re:Baltica.

Just like Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, the Law and Justice party-led Polish government also took pride in its alleged harsh anti-immigration policies. “Whoever organizes other persons to cross the border of the Republic of Poland in violation of the law, shall be punished by imprisonment from 6 months to 8 years,” the local law says.

But Madara’s story as well as low official figures on convicted Baltic drivers provided by Polish district courts near the Belarusian border region raise doubts.

Since 2021, the Bialystok District Court has only convicted one Latvian citizen; the Sokolka District Court, two Latvians and one Lithuanian; and the Bielsk Podlaski District Court, two Estonians, two Latvians, and one Lithuanian national.

Unfortunately, however, we don’t have numbers about those traffickers whose cases got labeled as “tourist transportation,” resulting in a quick release without conviction.

Meanwhile, the demand for drivers in the illicit business of transporting undocumented individuals is evident and escalating, highlighted by the surge in recent criminal cases related to this activity in Latvia.

Last year, a total of 26 cases were initiated; this year, that number has skyrocketed to 97, according to information provided by Latvia’s prosecutor’s office.

Lithuania, a neighbor to Latvia and a transit country on the migrants’ route to Germany after illegally crossing the Belarusian border, also sees this rising trend. Lithuanian border guards have detained 23 Latvians for illegal transportation in just the first half of this year, doubling last year’s total, based on data from our media partner LTR.

Colonel Oļegs Tribis, a representative of the Latvian Border Guard, explains this rising trend as a consequence of the “hybrid warfare” being conducted by neighboring Belarus. (The term refers to a decision by Belarus to push undocumented migrants into the European Union in retaliation for EU sanctions against Belarus, which has backed Russia in its invasion of Ukraine.)

This year, Latvian border guards stopped more than 9,000 people from illegally crossing the border between Belarus and Latvia, almost twice as many as last year.

Due to the pressure of illegal migration, Latvia closed one of its two main border points with Belarus in September. The crossing point, known as Silene, was used by around 1,200 people daily.

Closure of the Silene border crossing with Belarus. Photo: Leonids Kalnins, National Armed Forces, Latvia

The smuggling of migrants into Latvia and neighboring Lithuania and Poland escalated sharply in the latter half of 2021 when the regime of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko began pushing migrants across the border. This was a retaliatory response to EU sanctions imposed due to human rights violations in Belarus.

“I think this instrument of hybrid warfare—illegal immigration—will only continue,” predicts Tribis. It’s a way for Russia and Belarus to try to “destabilize the situation in Latvia.”

Editor: Sanita Jemberga (Re:Baltica)

Contributor: Fabian Schmid (Der Standard, Austria)

Technical support: Madara Eihe

Cover illustration: Re:Baltica

This investigation was supported by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund.

VSquare’s Budapest-based lead investigative editor in charge of Central European investigations, Szabolcs Panyi is also a Hungarian investigative journalist at Direkt36. He covers national security, foreign policy, and Russian and Chinese influence. He was a European Press Prize finalist in 2018 and 2021.

Inga Spriņģe is an award-winning investigative journalist, former broadcaster, lecturer, and one of two founders of The Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism Re:Baltica based in Latvia. Springe is a member of the major international investigative journalism networks, ICIJ and OCCRP. She covers topics ranging from propaganda and disinformation to social justice.