Pavla Holcová (investigace.cz)

Daniel Antoni, Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK)

Graphics by Lenka Matoušková 2020-07-16

Pavla Holcová (investigace.cz)

Daniel Antoni, Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK)

Graphics by Lenka Matoušková 2020-07-16

It is relatively common for animals that rank high on the list of the world’s most protected species to change hands in Central Europe. Illegal wildlife trade has become one of the most profitable branches of organized crime. Where is the red line that divides the world of big cats’ enthusiasts and those involved in criminal activities? What happens to dead tigers that die young in suspicious circumstances in legal breeding farms? They sometimes disappear into thin air.

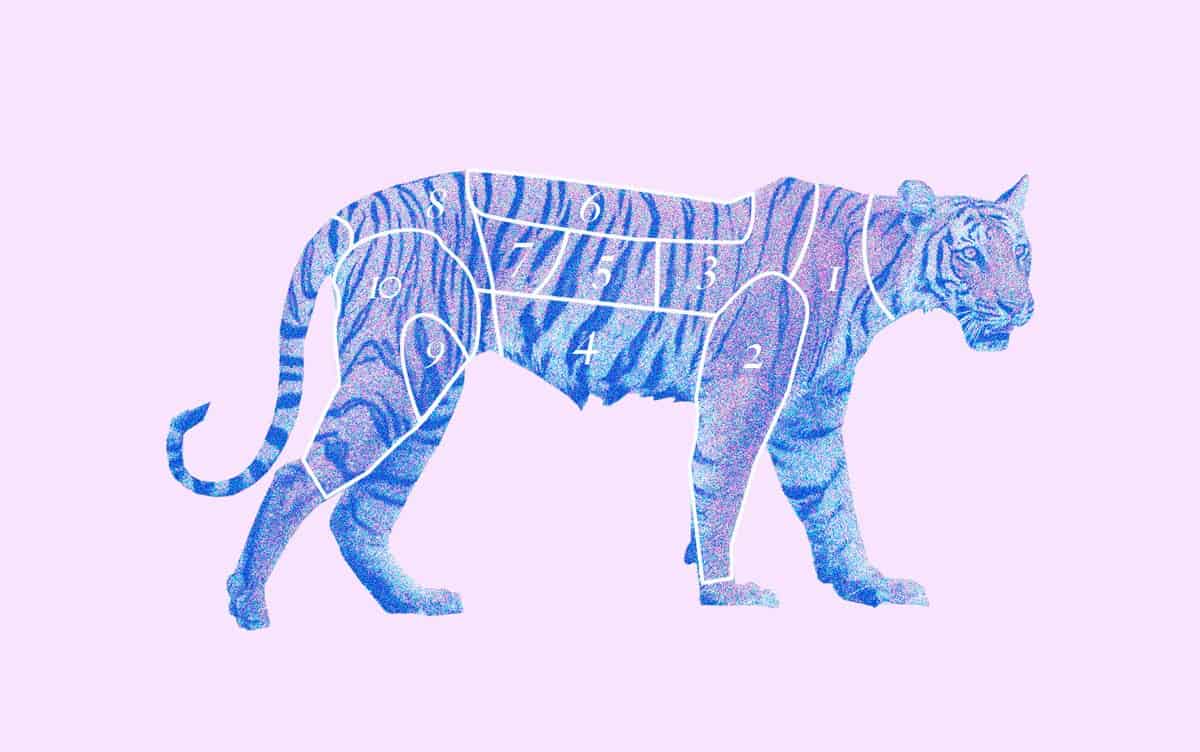

Each pound of tiger corpse may generate a small fortune. An adult tiger is made of over four hundred pounds of muscle, blood, bone, and fat.

Private tiger breeding farms operate on a large scale in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and are entering Poland. Yet, big cats bring profit not only as they captivate the attention of audiences at circuses and visitors at private zoos. Products made of tiger body parts reach mind-boggling prices as trophies or as valuable ingredients used in traditional Chinese medicine.

We have been working over two years with animal welfare organization Four Paws on analyzing and mapping illegal trade with tigers. This is first from a series of articles focusing on the role of Central Europe in global illegal wildlife trade.

According to traditional beliefs, tiger bones are “an excellent treatment for joints, but also a great treat for rat bites and laziness, and they fend off evil demons.” Ointments, charms, and balms that contain powdered tiger bone and fat supposedly have medicinal properties and are sold for thousands of euros – although you would only come across them on the black market. You cannot legally buy tiger ointment, the sale of the animal’s body parts for ingredients is strictly banned. On the black market, a gram of “glue” from tiger bones is sold for sixty euros. Processed bones of a single animal may generate up to half a million euros. And the tiger pelt itself costs thousands.

Those who seek to obtain such rare and banned goods know that it is easier and safer to illegally “organize” a tiger bred in captivity (or tiger bones) than have poachers hunt for the animal in the African jungle.

We reveal how the legal loopholes and loosen controls exploited by private exotic pet owners can be used to bypass laws that should otherwise protect endangered species.

In October 2019, Poles learned from a TV news bulletin that tigers are not only exotic animals they can see during a trip to a zoo. At the border crossing in Koroszczyn, Belarusian border guards opened a door of a horse lorry. Inside, in cramped crates and cages there were ten tigers, exhausted after 46 hours of the journey while fed only with raw chicken. The emaciated animals had been – officially – a donation from an Italian circus to a zoo in Russian-controlled Dagestan, the sender claimed to collect them across Europe from various sources. Belarusian border guards stopped the transport and the tigers were unable to travel any further – the lorry driver had defective transport documents.

One of the tigers died at the border crossing, the other nine were rescued.

For several weeks, Poles discussed and followed the plight of tigers removed from the lorry. Why did breeders, for whom the animals (or two tonnes of live flesh) were worth over a million zlotys, dispatch them on a 4,000-kilometer trip. Why did the Italian circus performers chose such a tortuous journey, as if they didn’t care if they make it to the destination alive?

The incident also marked Poland’s most publicized case of alleged illegal wildlife trade. By that time, few Poles had ever heard that tigers could be slaughtered or exported from Europe for slaughter. Few of them associate the acronym TCM with Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Journalists of a private television network TVN were able to establish that the Dagestan zoo is not operational and that the transport documents included an address of a chain store that sells alcoholic beverages. “The tigers were to be sold for parts,” the Poznań Zoo, which accepted some of the animals, warned. Was it an attempt to smuggle the animals across the border or – as its organizers claim – a harmless, selfless gesture, a gift of exotic pets?

Over six months ago, the authorities launched an investigation into the mysterious transport. As of publication date, the prosecutor’s office has not brought forward any charges.

2.

In July 2018, Czech police raided Ludvik Berousek’s breeding farm located just north of Prague. Berousek is a top breeder of big cats – tigers from his facility end up in many European parks or are turned into animal film stars. In the village of Bašť, where the farm is situated, the police found a tiger carcass in one of the pens. The tiger had been shot a short while before – there was a bullet hole in its neck. The wound was small, which meant that the tiger’s pelt might be sold. Nearby a pot lay, containing bones of killed animals. In the next room, there was an old freezer, with power cut off, full of a mix of rotting big cats’ flesh – Berousek also bred pumas, lions, and other predators.

Police raid over Berousek, source: Customs Administration of the Czech Republic

The raid on Berousek’s breeding farm was shocking not only for the activists who protect animal welfare. The Czechs suddenly began to talk about the events that unfolded. The fact that the Czech Republic may have been the centre of illegal tiger trade and the production of Traditional Chinese Medicine shocked the public opinion. Along with Berousek, the police detained his taxidermist (who cooked the body) and a Vietnamese dealer who placed products like tiger bone wine on a local market. Though Berousek claimed he only tried to preserve the skins for his private collection, the court of the first instance found the entire group guilty of violating the provisions of CITES.

CITES is an acronym for a document that is key in the fight against converting tigers into ointments and powders and against other misuses of animals on a verge of extinction. Its full name is The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and it lists the tiger as one of the most vulnerable species; it is also among the most rigorously protected ones. It is as a result of CITES (also called the Washington Convention) that tigers cannot be hunted, bought, or sold (or otherwise exploited for profit). All exceptions to that provision are strictly regulated, in theory.

3.

“There are fewer than 4,000 tigers living in the wild today. CITES was adopted to protect populations in natural habitats. To limit hunting. It is also there to protect animals bred in captivity and owned by individuals who are unable to look after them in a correct way,” explains Ryszard Topola, head of the Warsaw Zoo’s breeding department.

Tigers are listed in Appendix I of CITES, which means the level of protection is really high – and therefore international trade is strictly forbidden. You cannot just bring tigers into the EU, they cannot be taken outside the Union, either. As a rule, tigers cannot be put up for sale or bought, or used for any kind of profit – they cannot be bred for-profit and commercial exhibitions cannot be organized, either.

The ban includes not only wild tigers but also animals born in captivity or dead specimens or body parts – trophies, skins, bones, claws, fangs, and any products made using tiger body parts. All of this has been adopted to eliminate the demand for their skins and bones – as long as there is a market for such products, the tigers in the wild are not safe.

Tiger at the private zoo in Poland

However, captive-bred tigers are treated as Appendix II and can be traded with CITES papers. CITES and its EU equivalent, a regulation which introduces its provisions in member countries, make it possible to transport and commercially display animals under certain conditions. They can also be traded with CITES papers (within EU) or import and export permits (into or out of EU).

This is possible only if the animal received a special EU certificate that confirms its legal origins and makes them exempt from the ban on commercial activities. Such certificates may be obtained if the animal and its ancestry were proven to be acquired or bred in a fully legal manner, including compliance with all applicable animal and nature protection laws.

For animal dealers, the certificate for commercial use serves the same purpose as a vehicle registration certificate for car dealers – although selling cars without a valid registration certificate is not punishable by up to five years in prison.

4.

In the Czech Republic, it was already in 2013 when local customs police became suspicious that something fishy was going on that has to do with endangered species – they began to seize tiger bones and other endangered species products on flights between the Czech Republic and Vietnam. Customs officers were looking for a source of such an increased number of tiger products being smuggled from the Czech Republic.

The environmental control office offered a hint – the responsibility might lie with private, legal farms. Cases, when tigers die a suspicious death or disappear, began to be more frequent. The officials were puzzled by a high mortality rate among five-year-old tigers – these animals usually live up to about twenty years.

A CITES report in 2019 states explicitly that in the Czech Republic, an increase in the number of dead animals may be due to the fact that “some breeders might be involved in illegal trade in tiger products most likely organized by people from the Vietnamese community living in the Czech Republic.”

In 2016, a police operation began that ended up with the raid, seizure, and a court of the first instance finding Berousek, the animal breeder from the Czech Republic, and his associates, guilty. They appeal against the verdict. The case is still pending.

VSquare journalists, in collaboration with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), Investigace.cz, ICJK.sk and Four Paws analyzed and mapped the tiger trade. Although the current legislation imposes a lot of restrictions, it does not fully bind the traders’ hands – the footage we have obtained shows that there are ways to bypass the law.

5.

In the Czech Republic, the estimated number of tigers is about 390, only 10% of which are kept in zoos. The rest belongs to private zooparks, “bioparks” and individuals that turn the possibility of feeding, petting, and photographing with tigers into a profit. It is similar in Slovakia, where tiger breeding turned from a sign of prestige by 1990s criminal underworld leaders to a hobby.

“The breeding of big cats is incredibly widespread in our country and very often it takes place in completely unsatisfactory conditions and/or it is purely for profit”, commented Miroslav Bobek, director of Prague Zoo on Berousek case back in 2018. “Of course, it is not the case that every tiger or lion, with which you have your photo taken at a private company, ends up in a slaughterhouse or in a soup. [But] it is also a fact that taking a tiger or lion cub away from its mother, so it can be petted is, at the very least, bordering on abuse that leads to mental issues for the cub. It is these dubious breeding stations and “petting zoos” that form the base of the iceberg, whose tip is represented by Ludvík Berousek and his pals.”

In June 2020, Slovakia’s local Instagram star Zuzana Plačková (also known as Queen Plačková) posted several photos on her profile. The photos show her feeding and walking tiger cubs. Queen Plačková not only bragged about spending time with such cuddly animals but she also promoted the Slovak breeding centre and a private zoo called “Ranč pri Žiline.”

The images of tigers in captivity triggered a public outcry. In a public discussion, Plačková was criticized by animal welfare activists and removed some of the photos. Visitors at “Ranč pri Žilině” complained that young tigers were paraded in front of crowds of tourists. When they tried to defend themselves with their paws or bite, a whip was used to help control them.

A horrific accident was reported at the breeding centre in 2019. When a woman put her hand through the bars of the cage to stroke a tiger, the animal bit off her hand. The lawsuit before a civil court is still pending.

“Hardly anyone in this country would think of curing hemorrhoids with tiger fat. But going to a menagerie, cuddling some lion cubs and posting a few pictures on Facebook is a very common matter”, wrote Bobek shortly before the incident. “Unfortunately, most of those photographed with lions or tigers have little idea that they are not helping the animals. Quite the opposite! Moreover, the owners of the various menageries corroborate this illusion with falsehoods about how they are rescuing the lions and tigers. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

In some private tiger farms, like the one located next to Turá, visitors are not allowed. According to the Slovak weekly “Plus 7 dní”, local authorities looked into the Turá farm owned by the wife of the local mayor, which is home to around a hundred big cats, including 23 tigers and 11 lions. The police wanted to investigate a possible violation of plant and animal protection regulations by that farm – they acted on information that although the owner did not have a breeding permit, she was still trading of big cats. The owner, however, provided the necessary documentation and the police were forced to close the investigation.

The closed farms without a source of income from the visitors are financed only from trade: “That’s right, we breed [animals] here,” confirms one of the farm employees. “And we sell the young to zoos”.

6.

The London-based Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), which tracks the cases of tigers and their body parts seized by police and customs officers, estimates that nearly 38 per cent of live, frozen, and stuffed tigers seized by law enforcement agencies in the European Union in 2010-2018 originated in private farms.

Undercover conversations recorded in the autumn of 2019 in Poland that we obtained for verification reveal that some breeders are fully aware that there is a black market for dead protected species, and that exotic animals are sought after “for parts.” They are aware that such trade is a crime, but some of them were willing to reveal the know-how allowing to trade animals to certain fate while keeping the appearance of legality.

“I don’t know what can I talk about, all legal or illegal?” Tomasz N. said (we changed his real name for this publication). He owns one of the private zoos in western Poland. When he learned that he was dealing with an Asian businessman looking for rare species, he quickly turned to discuss the specifics.

“What do you mean, you don’t know?” the interpreter asks.

This is how one of the recordings that document the meetings between the alleged owner of a private zoo in China and Tomasz N., begins. The business meeting, recorded with a single shot, lasted five hours.

“I know people. Legal, illegal, no problem,” he explains.

“Do you have lions, tigers or do you know where to get them?” the Chinese visitor asked.

“As I say, if all of this is serious, and it is not because someone has come to secretly record me to cause a scandal, that’s not a problem,” the zoo owner probes his guests.

7.

In the autumn of 2019, a “potential buyer” from China visited several entrepreneurs in Poland looking for live tigers and tiger bones. He held meetings with owners of private zoos, breeders, and animal dealers. His interlocutors were trying to seal the deal and establish business cooperation – even when they heard that back in China their guests had links to TCM producers. Some of the traders declared outright not really care what will happen to the animals once they conclude the deal. They were only worried whether everything will look legal.

Tomasz N. is passionate about animals, he has been breeding them as long as he can remember.

“It started as my love, my passion. If I didn’t like animals, I wouldn’t be doing it,” he tells us as we speak a few months after the recorded meetings took place. “If I were to do it for money, I’d do something else. I have been breeding birds since I was twelve. I exchanged, bred species that are a challenge to breed. Later, we would have more and more animals and people wanted to see them, so my father suggested we set up a zoo.”

In his teens, Tomasz N. only had several birds. Today he is 30 and keeps over a hundred different species in a private zoo several kilometers from the Czech border. His zoo is an officially registered facility supervised by Poland’s General Directorate for Environmental Protection (GDOŚ).

There are over twenty zoos in Poland, several of which are in private hands.

Tomasz N.’s zoo is spread over nearly twenty hectares in a spectacular mountain setting. You can see lemurs, kangaroos, lynxes, gibbons, arctic wolves, meerkats, llamas, and prairie dogs. The conditions in which animals are kept differ from the conditions we know from public zoos – when we arrive there, it becomes instantly clear the facility is run by an amateur.

Tomasz N.’s garden was set up in 2012, although in the same year the Board of Directors of Polish Zoological Gardens and Aquariums objected to it being considered a zoo. Doubts were raised by the fact that Tomasz N. was selling animals, a scale of operation colliding with the sole purpose of zoological gardens: the protection of nature. Members of the Council were puzzled by the ambiguous wording in the application: “we are trying to acquire animals in a lawful manner.” Today, he explains that before his facility was officially recognized as a zoo, he had been selling “surplus animals” but he had to change his ways as a zoological garden emerged from his operation.

Eventually, his facility was officially certified as a zoo. Today, you can see his entire collection for 25 zlotys. Tomasz N. finances his zoo from animal transport services and the sale of animal feed.

“We operate on the principle that it was set up to benefit society. Because it is not for us, but for everyone,” Tomasz N. said.

8.

In late 2019, trade talks are held in Poland. The interpreter makes a short introduction: “This gentleman is the second-largest merchant in China and has many clients for tigers and lions.”

“No problem,” Tomasz N. says. “Tigers, lions, we can organize transport legally. We are officially a zoo, we can accept animals as the zoo because we have the number [so-called BALAI number, which allows its owners to legally exchange animals] like legal gardens.”

“Have you ever transported animals to China?” the visitor asks.

“I haven’t but my friends have. I have a friend from Prague who sends animals to Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates, wherever you need to send them,” explains the breeder.

Did he have in mind Berousek, the breeder from the Czech Republic, convicted of killing tigers “for parts”? As we have learned, in 2011, when he was just 20 years old, he was involved in a trade of leopards from Berousek – the leopards are worth as much as a million zlotys. Tomasz N. failed to provide further details about whether he knew him.

Tiger at the private zoo in Poland

Tomasz N. ushers his guests to a cluttered room with a fireplace. Hunting trophies hang on the walls, parcels with animal feed wrapped in black foil are waiting on large tables to be mailed. There are antlers lying about next to the fireplace.

Tomasz N. admits that he does not care about what happens to the animals: “If I had a sponsor and more space, I could breed animals. If it’s so that I can send [transports] and there is cooperation with China and I know that I can send animals, I would dispatch them alive. And whether they will take them to a zoo or elsewhere, it’s none of my business.”

He reserves that he personally does not want to kill any animals or send dead tigers anywhere. He knows the consequences, but he proposes another way: he could breed endangered animals, and select individual animals to be traded. Genetic material could even come from endangered species conservation programmes run by European zoos. All you need is some ambiguity in the papers.

9.

There are thirty-four tigers in Poland with a certificate issued by national authorities that allow commercial use of animals. All the animals are in zoos, all have their “registration documents” at the Ministry of the Environment. However, the list does not include animals born in captivity unless their owners intend to transfer them to someone else, transport, or profit from them. Such a tiger does not need a certificate for commercial use as long as it is a “private tiger” with no plans to monetise it. The list does not contain animals that entered Poland with documents issued by another EU country either. Private entities other than zoos and pet dealers must declare that they keep protected species only to the local poviat authorities.

Tigers kept in zoological gardens associated in EAZA enjoy two-tiered monitoring (EAZA is an association of zoos with a programme aimed at protecting endangered species, which includes breeding in zoos). Most of those animals who obtained documents in Poland are also included in the common database of animals, which every EAZA zoo can access. The database tells us that there are twenty-six tigers in Poland. In addition, the ministry’s list contains several more tigers registered by private zoos. The problem is that the total number of tigers in Poland is even higher – but captive-born animals are included in the ministerial register only deliberately, and if they were already purchased with papers, only the owner is in possession of the document.

We are puzzled by the fact the animals from Tomasz N. zoo, born in Poland, are not in the register. No EU certificate was issued to allow it to be kept as an exhibit in the enclosure, where you can see it when you buy a ticket. When asked about the tiger’s documents, Tomasz N. argued that the animal was exhibited legally and that he would only have to have a certificate if he wanted to send it overseas.

We asked about these regulations at the Ministry of Finance, as it oversees the National Revenue Administration (Krajowa Administracja Skarbowa), which deals with the fight against animal smuggling. Rafał Tusiński, an expert at the Ministry of Finance, argued that without proper documents, you may only own a given animal. All commercial activities – including public exhibits – are prohibited until you obtain the papers. You could go to prison for up to five years if you place a tiger on a paid exhibition without the necessary documents.

So far, no such sentence has been passed by courts in Poland.

10.

So where do private zoos may source their animals from? When we try to uncover the origins of the animal, we track it back to a private breeding facility – the tiger, before it ended up at Tomasz N.’s zoo, had belonged to Maciej Maciejewski, the owner of OKAPI Breeding Center.

Maciejewski is a large breeder of wild animals from Poznań. In March 2019, the city’s prosecutor’s office brought forward nineteen charges related to his operations, including the unauthorized placing of protected species on the market. The investigation was launched after Maciejewski’s former employees alarmed the ZOO in Poznan, which subsequently informed the prosecutor’s office, about the bad welfare conditions and suspicion of illegal trade.

OKAPI was nothing like a zoo – the owner for almost seven years kept it closed to visitors. Despite the name suggesting a breeding station, local authorities considered the farm near Poznań to be a “circus” – although it has never organised any road shows. What is it, exactly – a circus closed to visitors, without shows?

In Poland, there’s another set of regulations you need to face if you want to breed tigers. While being vulnerable as an endangered species, tiger is a deadly threat to humans. And while virtually everyone in Poland could acquire a protected animal, it’s only the zoos, research centers, and circuses that are allowed to legally buy and keep tigers and other dangerous animals. For a long time, the owners of dangerous animals got away with their tigers, pumas, lions and their hybrids simply by claiming they conduct circus activities – a trick that worked well with local authorities and inspections inexperienced in the matter, usually until more specialized authorities or courts took a closer look at it.

Maciejewski sticks to his guns and claims his breeding centre was really a circus: “Our animals participated in commercials, so it was entertainment activity. They [tiger cubs born in OKAPI] were shown by PKP Przewozy Regionalne [a railway company], a battalion of tactical aviation in Krzesiny, which operates the F-16s, and were also used by artists in music videos.”

“Did you get the money for it?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“You shared the animals out of your good will?”

“Take money from soldiers? When the president of the supervisory board of PKP Polregio came to thank me, as a thank you gesture, I asked him for a diploma, not for money.”

Screenshot of PKP Polregio advertisement

The answer could not be different. To legally perform in commercial activities, tigers born in OKAPI would require the certificate – and they didn’t receive it. But the circus involving high-value dangerous animals, giving no road shows but occasional “pro-bono” performances, did not seem credible to the judge.

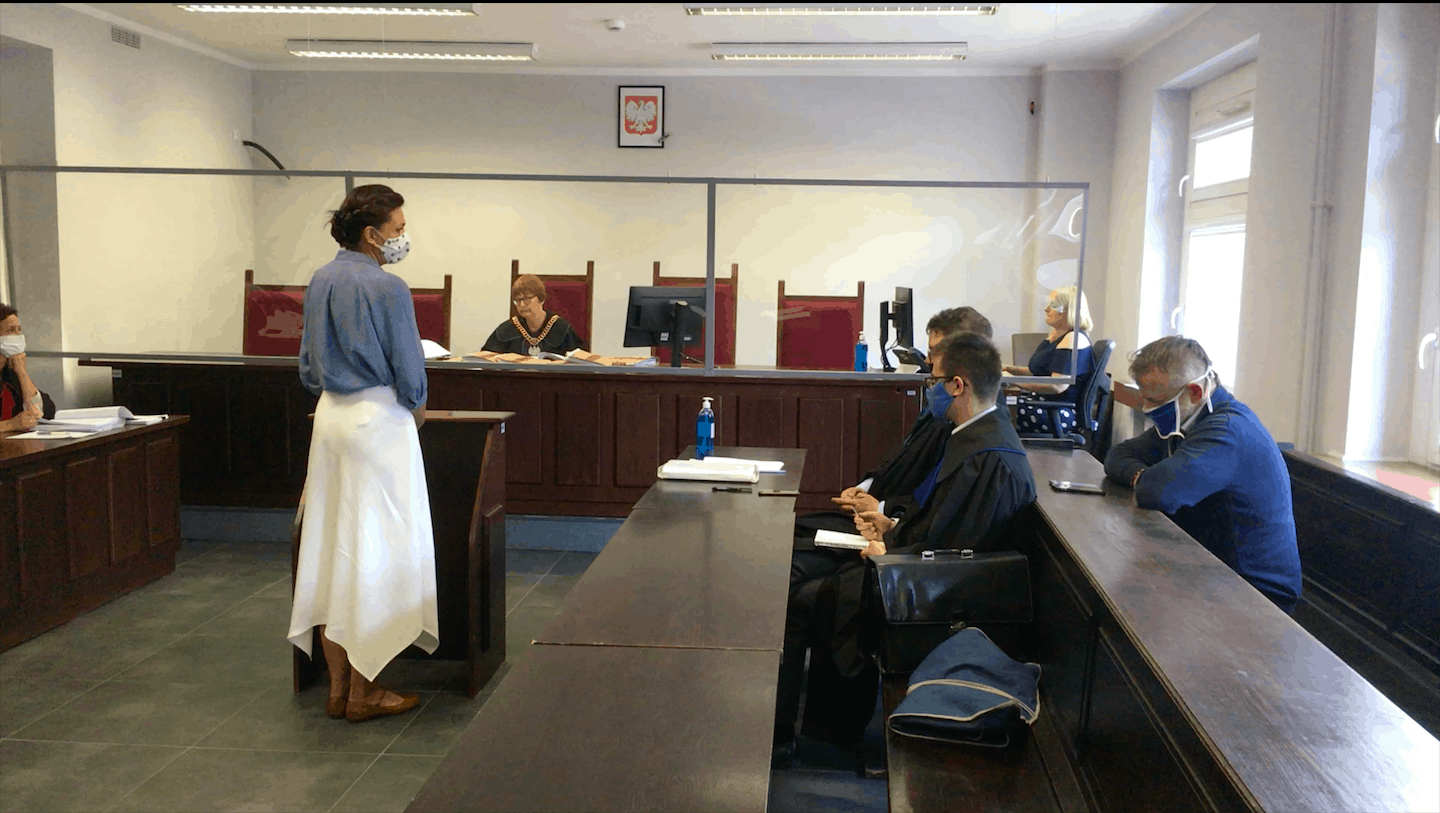

We talk to Maciejewski in June in the hallway of the Poznań court. That day, the court upheld the verdict: “OKAPI is nothing like a circus, the centre had no right to keep dangerous animals.” After the judgment, the State Treasury seized nearly forty valuable animals including tigers, leopards, pumas, macaques. The possession of dangerous animals by unauthorised persons in Poland is only an offence punishable with a fine of up to PLN 5,000. The seized collection is worth a lot more.

Maciejewski and Tomasz N. have known each other at least since 2011. At that time, Maciejewski’s breeding centre was just budding. Tomasz N. brought animal feed to Maciejewski’s facility and helped him transport big cats from the Czech Republic and Slovakia. When Tomasz N. registered his zoo in 2012, he exchanged animals with Maciejewski. Today, Maciejewski says that it was a sign of friendship. Friends swap animals in their collections.

11.

Large European zoological gardens, which are in the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA), exchange animals free of charge, to protect species and maintain biodiversity.

Private farms also benefit from an exchange of animals and donations – if the premise is approved by the veterinary authorities, it can participate in intra-community trade. But according to experts, the actual purpose of the exchange can be quite different, commercial. And money from the sale of protected species is transferred under the table or paid as a voluntary donation.

The prosecution against Maciejewski stands on a position that “most (if not all) donations of high-value animals were fake and were in fact a purchase/sale transaction” – an excerpt from the opinion of a CITES expert, Andrzej Kepel, PhD reads.

M. Maciejewski trial, Regional Court in Poznan

Finding clues in Maciejewski’s court documents, we went on the trail of animals that, according to investigators, passed through Okapi. Scarce documentation seized at the breeding farm indicates that at least three hundred animal species passed through the hands of the owner in nearly ten years. Among them, at least 720 animals from about 130 species protected by CITES. These are impressive numbers – most Polish zoos have fewer animals in their collection compared to the numbers handled by the breeder.

During the appearance before the Poznań court, Tomasz N. praised the accused: “Maciejewski was known for his breeding of rare and endangered species in his centre. (…) His collection might have been an envy of any zoo in Poland.”

An expert who examined the Okapi farm on behalf of the prosecutor’s office failed to reconstruct the fate of 75 per cent of the animals that Maciejewski allegedly handled. The owner has told us that it is because those animals have never been kept at Okapi. When talking to us, Maciejewski maintains that the only protected species he ever kept were those that were in the centre, except for a collection of turacos and three pumas he sent abroad.

12.

The world of exotic animal breeders is just a small circle where almost everyone knows each other. And everyone knows, made deals or has heard of Berousek, the breeder with 200 predatory animals. His tigers and lions were stars of movies like Quo Vadis, Zookeeper’s Wife, he performed with his lions in Polish circus. As Maciejewski created his farm, in 2011, two leopards were booked at OKAPI as a donation from Tomasz N.’s firm (back then, he was 20 years old) and his father. The animals were worth a total of up to one million zlotys – their source was Ludvik Berousek’s breeding farm in the Czech Republic. Today, Tomasz N. claimed it was him who he had given big cats to Maciejewski as a first move of an potential exchange. Maciejewski denied he ever met Berousek. He could not remember who exactly got him leopards worth a million zlotys. Yet the pictures that the prosecutor’s office found on his computer’s hard drive showed big cats living in terrible conditions – white lions and tigers with their young, lying next to circus platforms for training. Pictures were taken on the day leopards officially arrived at OKAPI. But the facility doesn’t have lions, tigers, or such platforms – they belong to circus base more than to a breeding farm. Ludvik Berousek owns such training equipment.

Maciejewski started to breed tigers – from parents officially imported from German zoo by yet another zoological garden but instead placed in OKAPI – in 2012. In four years, OKAPI already had over twenty big cats, including three adult parents and six tiger cubs. This is when the concept failed.

In 2016, Maciejewski filed a request for certificates for two young leopards born in captivity. He didn’t expect any problems – after all, their parents have legal descent from Berousek breeding farm. However, officials from the Ministry of the Environment had reservations whether OKAPI was a circus – if it was not, dangerous animals should have never been kept in there. The request to issue CITES needs a positive opinion of the State Council for Nature Conservation (PROP). The Council also assumed that the leopards had been brought to the breeding centre and are being kept there unlawfully. And although Maciejewski went all the way to obtain all the documents for the leopards and tigers he has bred, he has never received them. The first large-scale tiger breeding facility in Poland failed due to little offense. The last attempt to obtain papers for tigers took place just before the police raided the center and secured the animals.

What would Maciejewski do with the tigers once he gets the CITES papers? He would swap them with some zoo or other breeder for other animals, he told us. Just like that.

13.

Although they still had no certificates, two young tigers from Maciejewski’s breeding centre are transferred to Tomasz N.’s zoo at the end of 2015.

“Maciejewski said that he was waiting for CITES documents from the Ministry and that his centre ran out of space. The tigers were born there. Without the necessary documents, he could not take them abroad. I agreed to his offer [to take them],” N. explained in court.

Does Tomasz N. display those tigers legally or illegally? What is their legal status? We ask the Regional Directorate for Environmental Protection (RDOŚ), which oversees zoos and is responsible for the audit of CITES compliance, about their interpretation of regulations. It turns out the Directorate actually knows little about the operations of the zoos – inspections are scheduled for every three years. The last one took place in 2018. The next one has already been planned for 2021.

There are only minor issues: previous inspections had shown, for instance, that the documentation lacks the numbers and dates of documents that would confirm the animals were acquired from legal sources. RDOŚ kept reminding the zoo’s owner that the documentation should contain copies of certificates that lift the ban on commercial activities for all of his CITES animals. Some of them were never delivered, as the animals were already gone from the zoo. It was after our inquiry when RDOŚ realizes that they still got no reports regarding how their recommendations were implemented and moved along to verify it, requesting all documents.

Tigers at the private ZOO in Poland

So who really owns the tigers that were transferred from Tomasz N. to Maciejewski and which have no documentation? In court trial and during the conversations, Tomasz N. and Maciejewski consistently use the word “transferred” when describing how the tigers were moved. They never say “bought”, “borrowed”, “donated”, “sold”. Only that they were ”transferred.”

Maciejewski told us that he gave them to Tomasz N. but offers no particular reason. Tomasz N. explained, however, that the tigers were supposed to stay as a temporary deposit, and then they just stayed for good. “Were they borrowed?” “Transferred,” Tomasz N. corrected us.

The formula of “animal transfer” is really convenient and safe. If anything would indicate a transaction, both could have faced up to five years in prison.

14.

When we had a chance to interview Tomasz N. in June 2020, he told us: “Black market? We do not do such things because we do not profit from it. And it is against the idea of protecting nature.”

In the zoo, only one tiger (out of the two animals he got from his friend) survived. Tomasz N. explains the male tiger died when he was serving time in a British prison. According to British authorities, in 2015 his zoo was used as a cover to smuggle money under the guise of animal feed. Tomasz N. and his employee were stopped by customs service with nearly half a million pounds hidden in re-sealed bags of chicken pellets. A week earlier, a similar transport driven by his former employee had been seized by British customs officers, this time with a million pounds in cash. Both cars were used to transport animal feed from the United Kingdom to their zoo.

Investigators discovered they visited the UK up to eleven times in eight months prior to the arrest. The court failed to believe that sending small vans again and again to transport animal feed was more economical than organising a single shipment in a large lorry. Tomasz N., who claimed the smuggle happened without his knowledge and consent, was released after seven months of time he served in 2018. In his absence, the tiger dies, while less than 4 years old.

A business meeting in 2019. When the Chinese visitor asked if Tomasz N. would also be able to organise the delivery of tiger bones, he mentions that a tiger, which had died a few months earlier is still available. It had been stored in a freezer.

“The tiger will be in preparation. It will be prepared. It is frozen at the moment, but it will be prepared.”

“The pelt?”

“Yeah. Now it’s frozen, by people who are doing tiger … taxidermy.”

“What about the teeth and bones?”

“Well, the bones should be there, too.”

“So you still have them?”

“Well, if I contact them, they will be available. But does it have to be an entire skeleton or bones only?” “Does the head have to be there, too?”

“The head may be with the pelt.”

“So that’s no problem, we have it, it’s frozen but must be cleaned. There was an idea earlier to build a tiger skeleton, just a complete skeleton to be mounted, but if they haven’t done anything, it should still be in the freezer. I only need a trusted person who can transport it because it’s unofficial. I don’t like problems.”

The parties agree to contact again when Tomasz N. confirms the bones are available. Soon after the conversation, Tomasz N. sent an email, in which he used a code agreed earlier. He asked about the price that the Chinese were willing to pay for “lime” – they had previously agreed to call animal bones “lime.” Tomasz N. wrote that “lime” is separated and cooked (it’s a standard bone preparation practice). This is the moment when the transaction was discontinued – by expressing a desire to buy and stating the price, the surrogate merchant would commit a crime.

When we asked Tomasz N., whether he ever met some buyers for tiger bones. “You know, various people ask me about various things. Some view it as a joke, some are looking for an affair, you never know. I am not just a freshman on the job, I know that there are things we can do and that there are things we cannot do. I will never do them so that I don’t risk too much, that’s all.” He claims the dead tiger was disposed of. And he warns us to be careful what we write – as he has a riffle and substances to put animals to sleep in case of emergency and he would not like to use it another way.

Shortly after we ask directly about the recording. The zoo owner is not surprised and states he was bluffing the buyer. He had sensed something is not right. He was just curious and wanted to know what his guests are up to, and if the deal was serious, he would of course report it to the police. Amidst the judicial and extrajudicial threats that follow, he sends us a document stating that a local carcass collector picked up the dead tiger to deliver it to utilization plant. The paper proves the frozen tiger – the tiger pelt, the prepared skeleton – he pitched to his guests in September 2019 was disposed of five months earlier.

15.

It’s summer 2020 in the Czech Republic. Pavla Říhova, Czech CITES official, said that although the sale of dead tigers or any protected species by zoos or private farms is illegal, such cases are still detected.

“There is a procedure regarding what to do with tiger bodies. According to the veterinary law, they must be disposed of. They are disposed of by private entities that do not have to report to anyone. So, if someone brings a black plastic bag with 300 kilos of rotten flesh, no one really checks if it’s a tiger or not. They confirm that you brought a tiger there and they give you a document that says so. In a given municipality, even if someone suspects that a tiger breeder was doing something wrong, no one wants to go to the recycling plant and start looking for the right bag of rotten meat to check its contents.

Obtaining tiger bones from dead animals is called “posthumous poaching.”

According to the Ministry of the Environment, no CITES were issued in Poland for the remains of a tiger other than the two that died at the Poznań Zoo. The receiver, whom the previous director promised the skins for educational reasons, had to wait for about a year for the decision of Ministry to approve their request for a certificate.

“When the corpse is to be sent to an animal preparation company and given to someone else, in the case of an animal covered by CITES, it must be notified by a person who is the owner to the Ministry of Environment. Otherwise, such a transaction is illegal”, says Małgorzata Chodyła, a spokesman for the Poznań Zoo, as we ask about the procedure.

With only two tiger skins officially registered in Poland over the last decade, is it possible that the skins and bones of animals that died in zoos or farms find “unofficially” their way to the black market? What should happen to fallen tiger according to the law? ”An autopsy needs to be prepared on each dead animal, and then the body is sent for disposal,” a spokeswoman for the Poznań Zoo says. ”When a disposal company arrives, you need to pay them per each removed kilogramme.”

The price they pay usually amounts to approximately 10 zlotys per kilo. Therefore, the cost of disposing of a tiger’s body may exceed 3,000 zlotys.

A kilo of tiger bones can bring up to 1700 euros on the black market. The price of tiger pelt could bring 25,000 zlotys or more.

We followed the document the tiger’s owner sent us. It certifies the disposal of 300 kilograms of remains – tiger and antelope combined – not to utilization plant itself, but to a local collector, that should deliver the tiger’s corpse to the appropriate utilization plant. Both companies are supervised by the Veterinary Inspection that should keep a record of the documents. We established the final receiver to be a huge industrial plant, over 300 km from the zoo.

It turned out the inspector in charge of the plant is not able to confirm or deny the company ever has received and processed the tiger’s body. She said it’s something that is impossible to determine based on the documents they received from the middleman. As the documents don’t mention 300 kg of tiger carcass, but 2200 kg of unspecified “carcass” was delivered three weeks after the tiger was disposed of. “Good look finding your tiger”, says a veterinary inspection employee that wants to remain anonymous as we talk about the case. “These are nothing but words on a page and we process these documents as if this guarantee it really was it. But if you don’t catch anyone red-handed, you have to take the word for it.”

16.

October 2019. The last days of the Chinese visitor’s journey to Poland overlap with the seizing of a shipment of tigers that set off in Italy and was stopped on the Polish-Belarusian border. Poles learn that the transport may have been related to the process of sending live tigers to Asia for the production of ointments and magic powder from tiger bones.

The visitor from China cuts the trip short and breaks off contact with breeders. His recordings are passed on to OCCRP, their verification introduces us to the ambiguous world of exotic pet breeders.

We talk to Tomasz N. at the end of June 2020 about Berousek’s case.

“On the one hand it’s bad, but on the other hand, it may be brutal, but how is this tiger different from domesticated pigs? Everyone slaughters pigs, and these pigs sometimes are more intelligent than dogs. So, this topic is debatable.”

Konrad Szczygieł is an investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL. Previously, he was a reporter at Superwizjer TVN and OKO.Press. Since 2016, he has worked with Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He was shortlisted for a Grand Press award (2016, 2021) and an Andrzej Woyciechowski award (2021). He is based in Warsaw.

A senior OSINT researcher and data analyst at FRONTSTORY.PL, Julia Dauksza has participated in many cross-border investigations. Previously, she collaborated with NGOs in Poland. She has been shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2021, 2022). She was the recipient of the 2023 Bertha Challenge Fellow.

A Czech journalist, Pavla Holcová is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism. She is an editor at OCCRP and a member of ICIJ. She was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University (2023). Pavla is the winner of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Award and, with her colleagues Arpád Soltész and Eva Kubániová, the World Justice Project’s Anthony Lewis Prize Award. She is based in Prague.

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.