On 21 February 2018, investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, were murdered in Veľká Mača. On the sixth anniversary of the murder, the Ján Kuciak Investigative Centre prepared a series of interviews with Ján Kuciak’s colleagues and friends. Journalists who worked with Ján on a range of stories recall how they learned about the murder; how their professional and personal lives changed after it; what they worked on together; and how they perceived him. These interviews were conducted over the course of 2023.

How do you remember the day you learned about the murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová?

Annamária Dömeová. Photo: ICJK

Annamária Dömeová, investigative journalist at Aktuality.sk:

“I saw Janko the day before the murder. I was heading home. Janko was there to see me off and I asked him if he was going out for a smoke because he used to be a heavy smoker. He said no, that he had quit smoking because he might smoke when he was old, but now he needed to save his money for other important things. I had a little baby, so we talked about children, and he told me that he and Martina couldn’t wait to have a baby. I found out about the murder from Bernard Slobodník, who called me at about 7:22 in the morning and said, ‘so this Janko guy was murdered’ and I absolutely didn’t understand what he was talking about. I found it completely absurd. Then he started describing it to me—that he and Martina had been found dead in Mača. I called the editor and he was already crying and confirmed it for me.”

Martin Turček. Photo: ICJK

Martin Turček, investigative and data reporter at Aktualty.sk:

“Our editor-in-chief, Peter Bárdy, wrote to our group of reporters in the morning and told us to come to the newsroom. I thought it was about a lawsuit or about an argument over which investigations to cover. I tried to arrive early, but because I usually got to work a little later than my colleagues, I was actually the last of us investigative reporters to arrive. Everyone was already sitting in the conference room. After Peter Bárdy’s message, I was in a hurry, so I was probably a bit out of breath, and Peter asked me if I knew what had happened. He said—he had probably repeated it several times—that they had killed Ján, which must have been extremely difficult for him. I don’t remember how long it took me to process that information: that something like that could happen; that it really did happen; and that this wasn’t some weird dream. That now, really, every day when I wake up, Jano won’t be there, won’t be my colleague. It’s giving me a hard time.”

Miro Kern. Photo: Denník N

Miro Kern, journalist at Denník N:

“It was pretty horrible because I was one of the first to know that morning. I went to work early, so I was there at eight or before eight. I was sitting across from Monika Tódová, who was one of the first to find out, and I think it was honestly a shock. We had just then seen that Nový Čas or some tabloid had issued a report in the morning that a journalist had been killed and that it was in Veľká Mača. I thought to myself that it must be someone from regional journalism and then it occurred to me that Veľká Mača is the area around Sereď where the drug gangs operate. It didn’t occur to me at all that it was going to be a journalist from a national media outlet and only after a while did we find out. And we were really completely freaked out.”

Xénia Makarová. Photo: ICJK

Xénia Makarová, investigative reporter at the Stop Corruption Foundation:

“Still…even after all these years, it’s a difficult topic. I was at home because I had sick children and I remember seeing [the news] on Mr. Beblavy’s profile [on Facebook]. Then he deleted it, it was early in the morning and the rest of the family was getting ready for work and school. I was completely paralyzed on the stairs of our house and I was trying to call wherever I could to see if it was true and I was hoping it was just some mistake.”

Zuzana Petkova. Photo: ICJK

Zuzana Petkova, Director of the Stop Corruption Foundation:

“I was late for work because it was such a cold day: Quite a lot of snow was falling and my car battery froze, so I couldn’t start it. I walked and when I arrived I was late and I saw that the whole newsroom was in such a strange mood and everyone was looking at their keyboards and no one had the courage to look at me. It was only when I repeatedly asked what had happened that Filip Obradovič, then my colleague, now an editor at Dennik N, told me that Ján had been murdered. I thought he was joking, I said that it wasn’t funny at all, that he should stop it, such a horrible thing, that it wasn’t funny. I sat down at my computer and opened up the first news site and Ján’s picture popped up. I still couldn’t believe it for a moment and then I actually broke down. A colleague who had some medication with him gave it to me to calm me down. I called Marek Vagovič because I still didn’t want to believe it and I found out that it had happened and then I went to see him at Aktuality where we talked about it for a long time.”

How do you remember Ján Kuciak as a colleague?

Annamária:

“Janko was extremely thorough, conscientious. We used to make fun of him because he didn’t even go to lunch, he just ate in front of the computer and had all these Google documents ready where he analyzed individual people.”

Mária Benedikovičová. Photo: Denník N

Mária Benedikovičová, investigative reporter at Denník N:

“He was fantastic. He was friendly and had no problem sharing information, even though he may have perceived the other journalist to be a competitor, he didn’t take it that way at all, he was just about the cause, making it public and moving things forward.”

Miro:

“He was very nice, very polite and helpful. I didn’t actually want anything from him in particular, but he still went to the trouble of looking something up for me despite the fact that I’m from a different company. He spent some time at night looking for something to just selflessly send it to me. That’s very unusual.”

Were there any stories, investigative pieces in the works with Ján Kuciak during that period?

Annamária:

“I had just come back from maternity leave. We met and started working together a week before he was murdered. We had already agreed on some things, we were already in the field together.”

Mária:

“We did call each other occasionally. When he was working on a story, he used to contact me to see if I could help him with a phone contact or something that he wanted to go over, because at that time, when he was active at Aktuality I was on maternity leave and I was writing relatively less.”

Martin:

“In those short two months we managed to write several articles together. Jano, when he found something, let me know about it, and we worked on it together. I helped him a little bit with little things related to his last article. I remember with fondness how we used to look at, for example, photos from Maria Trošková’s [Robert Fico’s former aide who used to be topless model prior to that, and as Ján Kuciak’s last article revealed, also had links to the Italian mafia ‘Ndrangheta] social networks and we felt bizarre, and our colleagues used to joke with us about whether we considered this to be journalism and whether this was the kind of investigative work we wanted to do. But we did not have anything else in the works when he was murdered, we managed to publish the things that we started together. Except for his last article, which didn’t come out until a few days after the murder.”

Xénia:

“I’d called him a few days before. He told me he was working on something big, that I’d find out, that it was awesome. So I told him I was excited and that I hoped we could get together again for a drink or a beer and he’d tell me about it and that I’d love to read it. I wanted him to give me some information from the property register, specifically, it was about the villa of the then minister Robert Kaliňák because Jano was not only very clever and very smart and knew how to work with data, but he was also very systematic, so for example, when he bit into somebody, he collected all the information about them from the registry, through FOIA requests, and so on. I found myself going to dial his number two or three more times after the murder, because I wanted to know if he had any files, and I said to myself, “Don’t call, Xénia. There’s no point.”

Zuzana:

“We were actually still working on [Marián] Kočner at the time. Also at that time, we were dealing with the suspicious tax returns in Donovaly, of which Kočner is now accused. It was the kind of thing that we had been working on together for several months. Shortly before that, we dealt with the Panama Papers, where we also had such people popping up, such as Kočner’s son-in-law and various other people who were linked to Slovak oligarchs. These were the kinds of topics that we dealt with. For example, Jano didn’t tell me that he was working on the Italian mafia with Pavla Holcová, I didn’t know about that. Ironically, that week—this actually happened on Monday—on Thursday of that week we had a beer together and Marek [Vagovič] said that Jano wanted to tell me about the Italian mafia because he was approaching the final stage of mapping its activities in Slovakia.”

How did the murder affect your work life and work in the newsrooms? Did it change anything about it?

Annamária:

“In the first wave, it whipped everybody into suddenly becoming an investigative journalist. We just all got into it so that Ján’s death, which we all regret to this day, and of course we would have traded his life for anything, would not be in vain. And in that primal moment, it brought us very close together. We had articles that were produced as part of the All for Ján collaboration, and we discussed them with each other, and there really was such a sense of belonging. I think to a certain extent that stayed, that we don’t see each other so much as competitors anymore, and the collaboration has stayed.”

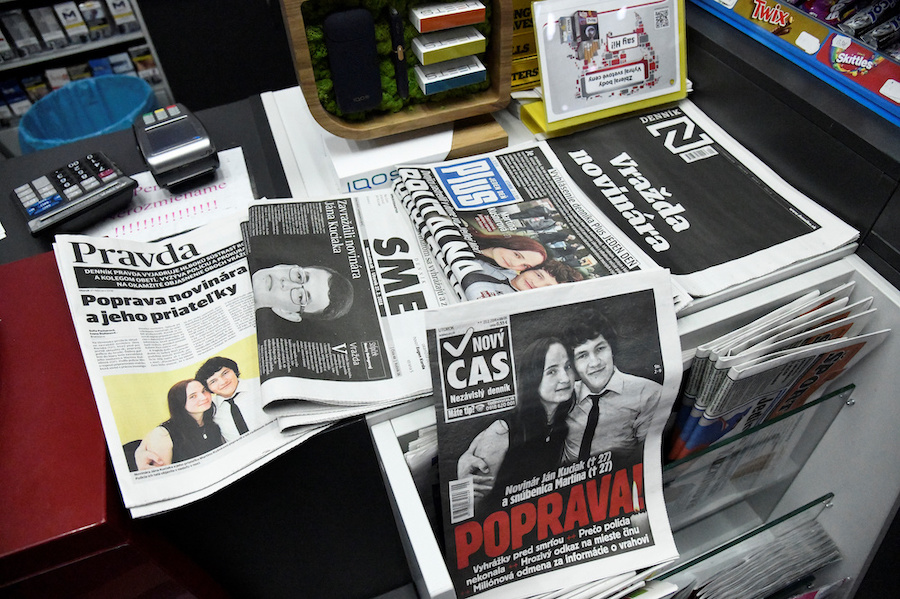

Front pages of Slovak newspapers in Trnava, Slovakia, February 27, 2018. Photo: RADOVAN STOKLASA / Reuters / Forum

Zuzana:

“The very next day or two after that, we put together an informal group called All for Ján, where there were a number of editors and we basically went through all of Ján’s notes and Ján’s diaries, the stories he had worked on. We split into groups and we started working on those cases. Adam Valček [then investigative reporter of SME] and I started to finish another story that was related to Technopol, which was also a case connected to Marián Kočner. I remember that Marián Kočner called me because of this piece, and he was quite aggressive, or rather sarcastic and snide, and he called me while I was in the playground with my son, and the day after that he was actually arrested. Parallel to that, there were interrogations going on at the police station, where a number of journalists were offered protection by the police if they felt threatened. I didn’t ask for that protection because I couldn’t imagine the police going everywhere with me, and for me at that time it was paramount to finish what Jano had started and perhaps somehow, through my investigative work, to find out who might be behind Jano’s murder. I couldn’t imagine meeting some sources who didn’t want to be seen in the presence of the police, it wouldn’t have been possible. And the other thing was that my older son, who was 16 at the time, was obviously terrified of it. Later on, it turned out that Kočner and his surveillance squad were also watching me, and even my older son is in several videos and photographs, so I didn’t want to scare him with the presence of even more police officers. But I won’t lie: I was scared a lot of times. When I was walking down the street in the dark, for example, I looked around to see if anyone was walking behind me.”

Martin:

“Neither my work nor how I approach it has changed. What’s changed a little bit is that it has an ending more often. It’s just that now more often things get to the police investigators, for example, and some of them start prosecutions, so more often one also sees some end of one’s work on the side of the state, but otherwise the principle remains the same. But certainly it occurs to every person after a murder what they can be more careful about.”

Xénia:

“I was pretty much out of it. But fortunately Zuzka Petková and a group of journalists took it upon themselves to finish Ján’s piece and that’s what helped me tremendously: That we bonded and stuck together. I felt that if there were any hints, there was someone to turn to. And I’m not at all surprised that some of my colleagues at the time didn’t trust the police who were offering them protection. At Trend [where she worked as an investigative reporter previously], the editor-in-chief Oliver Brunovsky was very supportive if we felt threatened, and that helped me a lot. And it certainly had an impact on me and still has, but not in the sense that I’m afraid to go into certain topics. Rather, I’m more careful about how I communicate, when I make phone calls, what questions I ask, and when I email. I think people in newsrooms have taken a number of precautions as well, and I’d probably be lying if I said that we’re not all more careful. I think the fact that I’m not afraid to go into topics shows in our work at the Foundation, but there’s definitely more caution, I’m more aware in the rearview mirror when I’m driving, if I’m being followed when I’m working on something more difficult.”

How has the murder of Ján and Martina affected your personal, family lives?

Annamária:

“It was very difficult for my husband because he doesn’t come from a journalistic background at all, he has absolutely no experience with how we operate and what it’s like. And really, I had a child who was a year old at the time, so we had debates at home about whether we felt threatened and whether we needed protection and whether I would hang up this journalism thing, but we agreed at the time that I would carry on.”

Mária:

“Of course it hit me very hard. I have to admit that I think about Ján a lot. When I see what’s going on, sometimes I feel that these things are not moving forward at all…then I say to myself that for God’s sake, I can’t give up, after all, Jano was silenced in cold blood, if only out of respect for his memory.”

Martin:

“Jano and I were friends, so in that respect it affected me, but my personal life not so much. I remember my mother being very scared for the next several months or maybe even years and having bad dreams about what might happen to me. I’ll admit that I didn’t. I don’t get threats, I don’t remember getting any, and this may sound controversial now, but I will admit that if someone told me on the phone that they were going to look for dirt on me, I wouldn’t even have given it a second thought. So, as far as family life goes, the thing I really remember most is my parents being scared. Somehow that fear didn’t sway me. On the contrary, up until now, I think that, as tragic as Ján’s murder was, it’s even more the case now that nobody will allow themselves to do anything like that, to order a murder of a journalist, because as much as Kocner or the convicted Zsuzsová might have irrationally believed in their own invincibility, and as much as they might have believed that nobody would ever investigate anything, that nobody would ever find out anything, that nobody would be held responsible for that murder—this was not the case. Which is to say, I think we live in a safer world…though maybe that’s too optimistic.”

Miro:

“It touched me very much. Ján and I didn’t know each other very well, only professionally, and we talked maybe a few dozen times, but we didn’t have a friendship relationship. But it’s just a thing that never happened here … but it touched me personally and I’m still shocked about it. And I know that even one of my colleagues has left the profession completely as a result of this as well, so I know it’s affected everybody and of course my family.”

Xénia:

“I had young children at the time and I found support at home I thank my husband for that. But sometimes he asks me to do things so that I don’t endanger anybody at home. My mother also asked me whether I don’t want to do something else, and why do I have to do this.”

Zuzana:

“I’ve been lucky that my family has always supported me in what I do, especially my husband. I know journalists whose marriages or relationships have fallen apart even after this and maybe as a result of this. It wasn’t my case. On the contrary: We sort of got closer together and started to care more about each other, but the fact is that my older son maybe has some anxiety and fear about it and I can sense that in my younger son who was two years old at the time and he couldn’t perceive with his mind yet, but maybe he could sense some of our anxiety and tension at home. He’s sensitive about where I’m going, whether someone is threatening me, or whether someone might attack me, hurt me as a result of my work. He’s 8 years old now and he’s still sort of sorting it out because he can read things on the internet now, he knows that history. In the meantime, I’ve become friends with Martina Kušnírová’s mom, Zlatica, so every time we go to the east of Slovakia, we go to see her and my son, and Zlatica has foster kids, my son plays with them, so he’s also taking in the whole Ján and Martina thing, and he’s worried about me and whether what I’m doing could put me or our family in danger.”

Demonstrators attend a protest called “Let’s stand for decency in Slovakia” in reaction to the murder of Jan Kuciak and his fiancee Martina Kusnirova, in Bratislava, Slovakia March 9, 2018. Photo: Radovan Stoklasa / Reuters / Forum

Didn’t you consider stopping doing investigative journalism after the murder?

Martin:

“Absolutely not.”

Zuzana:

“I didn’t think about quitting. Of course, we have changed our working style a little bit—that is, we have started using some encrypted apps or sharing more information with sources through face-to-face meetings rather than over the phone or through some intermediary. My nature is such a combative one, so it rather set me off to go on and do something to make sure that that situation doesn’t happen again and that the people who have dared to take on Ján in our society are eliminated or, if they are proven to have done what they have done, are punished. Of course, I joined the Stop Corruption Foundation because I felt that I could not only describe the scandals and problems anymore, but that I need to also push for their solution in some way through lobbying or activism. I didn’t think about quitting, but even if somebody did quit, that is if journalists either started doing a different type of journalism or left media altogether, I don’t blame them at all, because it was a thing that shook everybody who was doing investigative journalism.”

This article was originally published in Slovak on icjk.sk.

Karin Kőváry Sólymos is a Slovak journalist at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak. Previously, she was an editor and presenter at the Hungarian channel of the Slovak public service media. During her university years, she was an analyst for the only fact-checking portal in Slovakia. She was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.