Anastasiia Morozova (FRONTSTORY.PL) 2023-11-22

Anastasiia Morozova (FRONTSTORY.PL) 2023-11-22

Poles in the Netherlands organized the assassination of a journalist— who supported a witness in a brutal mafia trial. We reveal how they ended up at the center of the Dutch underworld

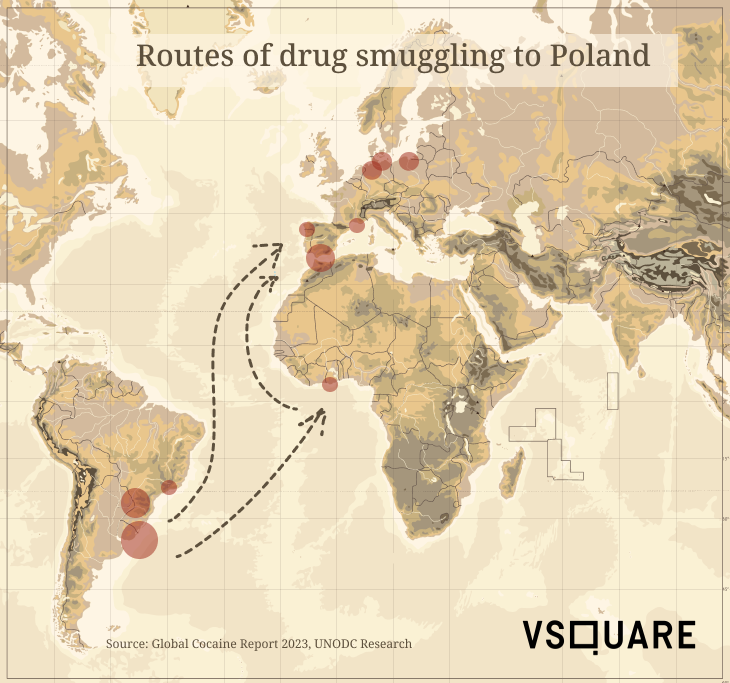

Dutch drug battles are a piece of a larger picture. Polish ports are part of it: One of the smuggling routes cuts through here. One of the most important ones, since the outbreak of war in Ukraine

Another piece of the drug puzzle? The Polish laboratories that mix cocaine before the drug hits the market.

In March 2021, the trial of the so-called “Mocro Maffia” was set to begin in Amsterdam. The “Mocro maffia” is the name given by Dutch police to a Moroccan gang operating in the Netherlands and Belgium. The gang specializes in drug trafficking. The number one defendant was Ridouan Taghi, the boss of the criminal group. It was a unique and high-profile case, and the popular journalist Peter R. de Vries got involved—supporting the witness, who spilled the story of the whole dangerous gang in court.

A few months later, on July 6, de Vries was shot in the center of Amsterdam, moments after leaving a TV studio. There were two assailants. The first was Delano G., a Dutch rapper of Antillean origin. The second, who was supposed to organize the escape from the scene, was Kamil E. from Poland. He is a taxi driver from Silesia who was hired by Mocro Maffia. Two other Poles with links to the Dutch underworld were also implicated.

Peter R. de Vries died in a hospital nine days after the attack. The murder shocked the Netherlands—and showed that violent gangsters do what they want on the streets.

The article is part of #NarcoFiles: The New Criminal Order, an international journalistic investigation into global organized crime, as well as its methods and influence. It is also the story of those who are trying to fight back. The project, led by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) in collaboration with the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), was made possible by leaked emails from the Colombian prosecutor’s office, which found their way to FRONTSTORY.PL and more than 40 media outlets around the world. OCCRP reporters analyzed and verified this material, as well as hundreds of other documents, databases, and witness accounts.

Gangster and confidant

The Mocro Maffia is an organized crime group that has been terrorizing the Netherlands and Belgium for years. Formed in the 1990s, its name comes from the word ‘mocro,’ which is used in the Netherlands to describe a person of Moroccan origin. Details of the group’s activities have been revealed, thanks in part to a report by the Colombian police, which found its way to journalists, along with documents from the Office of the Attorney General of Colombia.

The Mocro Maffia smuggles drugs from South America and Africa, orders kidnappings and murders, and acts unscrupulously. In March 2016, someone left the severed head of a 23-year-old drug dealer outside a shisha pub in Amsterdam. “It’s a gangster warning like from The Godfather,” crime reporter Peter R. de Vries said on television. De Vries was an authority on organized crime in the Netherlands, notable among other things for his book on the kidnapping of beer magnate Freddy Heineken (1983) and investigations on his own television program, Peter R. de Vries, misdaadverslaggever (Dutch crime reporter).

In the last months before his July 2021 death, de Vries decided to help the justice system get evidence against the Mocro Maffia.

How? First, in 2017, an extensive testimony of 1,500 pages was given to authorities by Nabil B., a former subordinate of Ridouan Taghi, the boss of the Moroccan mafia. He paid a heavy price for his honesty: a week after it came to light that he was turning on his gang buddies, his brother was shot dead. A year later, in 2019, Nabil B.’s photo mistakenly ended up on a file accessed by the defendants in the Mocro Maffia trial. Soon, his lawyer, Derk Wiersum, was also killed.

Nabil B. was desperate—and a fan of Peter R. de Vries’ show. In 2020, as reported by, among others, the UK’s The Guardian, Nabil B. decided to invite de Vries to join his team of court attorneys as a “confidant.” The reporter agreed— and found himself in the sights of Ridouan Taghi (speciality: commissioning murders and drug trafficking), who was arrested in Dubai.

Peter R. de Vries in 2017. Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0

A week before the assassination attempt, the journalist met with authorities about possible protection. He received an offer: ten armed officers, day and night protection. He decided that this was too much and did not agree to any protection.

“Uncle” orders the killing of a “dog”

Delano G. received a message: a photo of de Vries, underneath which there was a short text. He got this strange text message from a Pole, Krystian M. “This is the dog you have to kill,” wrote the 27-year-old Pole. Krystian M. is from Hrubieszów, where, until a few years ago, he played football in a local club and ran in inter-school competitions.

It was Krystian M. who organized the attack on the journalist. We know this from the testimony of a star witness nicknamed “Eddy”. Eddy is also Polish and knew Krystian M. well. He came forward to the police when he heard about the murder. Thanks to the help of Paul Vugts, a journalist from the Dutch newspaper Het Parools, we have excerpts from “Eddy’s” testimony.

He and Krystian met in 2020 through a mutual friend, also a Pole. “Eddy” helped Krystian from time to time; for example, “Eddy” registered Krystian’s cars in his name. How did Krystian M. come to gain the trust of the Moroccan mafia? “Eddy” does not know. “Krystian is very popular in the Netherlands,” he said simply. He claimed that his colleague had already killed someone on behalf of the Moroccan mafia before. “He once told me that he had nightmares about it,” said “Eddy.”

Krystian M. lives in Ochten, a small village in the west of the country. He came to the Netherlands with his parents as a teenager. One day, he told “Eddy” about his plans to kill a well-known journalist. The job could fetch 150,000 euros: 100,000 for the shooter, 50,000 for the driver. The order was from a man called “uncle,” said Krystian M. Who was he? On the basis of messages intercepted from Krystian M.’s phone, investigators established that the “uncle” was Ridouan Taghi, the head of the Mocro Maffia.

Moments after the murder, Krystian M. left for Poland for a month. When he learned that the detainees in the murder case were not testifying, he returned to the Netherlands. He continued to work for the criminal underworld: arranging weapons, watching over the money. For the de Vries murder case, the police do not have to look for him: When, in the autumn of 2021, “Eddy” incriminated Krystian with his testimony, the Pole was already in custody for his involvement in gangster blood feuds.

He always wore a medical mask at the trial. He does not want the media to publish his image.

Assailant and driver

Krystian M. was in contact not only with Delano G., but also with his driver, Polish national Kamil E.

Kamil E. likes combat sports and football and comes from Silesia. Tall, powerfully built, he sports a goatee and tattoos on his neck. In the Netherlands, he lived first with his partner’s parents, then with his partner and children in Maurik, a town of 4,000 inhabitants. He frequented the local gym.

Shortly before the attack, he was stopped while driving his car. The police suspected that there may have been weapons in the car. But they found nothing and sent the Pole on his way. A few days later, it was he, Kamil E., who drove Delano G. to the scene of the planned murder.

“I didn’t kill anyone,” he went on to say during his first interrogation before the court. It’s true: his job was to take the murderer away from the scene as quickly as possible, burn the Renault Clio, and get rid of the number plates. Those were his instructions. The plan failed: Delano G. and his driver Kamil E. were stopped on the motorway outside of Amsterdam less than an hour after the assassination.

With Kamil E. in custody, the Mocro Maffia planned to kill his mother (a resident of the small town of Tiel in central Holland) if he starts to testify.

Without a silencer, it’s a lynch

The Polish trail does not end with Kamil E.. In September 2022, two police officers arrived in Ostrow Wielkopolski with a European arrest warrant. Together with three Polish uniformed officers, under one of the gray blocks of flats, they came across the young man they were to arrest: Konrad W., soon to be extradited to the Netherlands to face trial for the murder of Peter R. de Vries.

The policemen knew who they had: the man has tattoos on his neck, cheeks and forehead: “Love”, “Life”, “Mental.” On entering the flat,, the police officers found several mobile phones and 79 grams of white powder. The police tester turned orange: amphetamine.

Konrad W. (born ’92, lower secondary school education, plumber) was surprised: he claimed that he only knew about the journalist’s murder from the media. On the day de Vries was shot, he was in another city. He did not admit his guilt and claimed that he had no idea why those who had already been caught were slandering him.

The Dutch prosecution has a different opinion about Konrad W.: they believe that he was in contact with the assassin Delano G. and his driver Kamil E. just before the assassination. That he passed on key information to them. He is also believed to have helped arrange for weapons and a car, and was even considered as a shooter.

There is another clue that links him to the Dutch criminal world: In Rotterdam, Konrad W. worked in container handling—ina port where 70 tonnes of cocaine were seized in containers in 2020 alone.

Why was it the Poles who were commissioned to kill Peter R. de Vries? Does this mean they are high up in the criminal hierarchy in the Netherlands? One Dutch journalist, well acquainted with local realities, describes them not as masterminds, but as “soldiers ready to pull the trigger.”

Today, in addition to the three Poles and the rapper Delano G., two other Dutchmen who were alleged to have assisted in the attack are sitting on the defendant’s bench. The prosecution is not expected to present its proposal for sentencing in the case of Konrad W. For Krystian M., Kamil E. and Delano G., however, everything is clear: each faces life in prison for murder and participation in a terrorist group.

Smuggling routes

The Benelux countries are key points on the map of global cocaine smuggling, which is dealt with by Mocro Maffia.

According to a report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and Europol, a total of 213 tons of cocaine destined for the continent were seized in Europe in 2020 alone. Most of this was in the ports of western EU countries. The largest amount of cocaine in the EU was seized in Belgian, Dutch and Spanish ports. Ports in the eastern Balkans—Albania, Montenegro and Croatia—are important distribution points for cocaine in Europe.

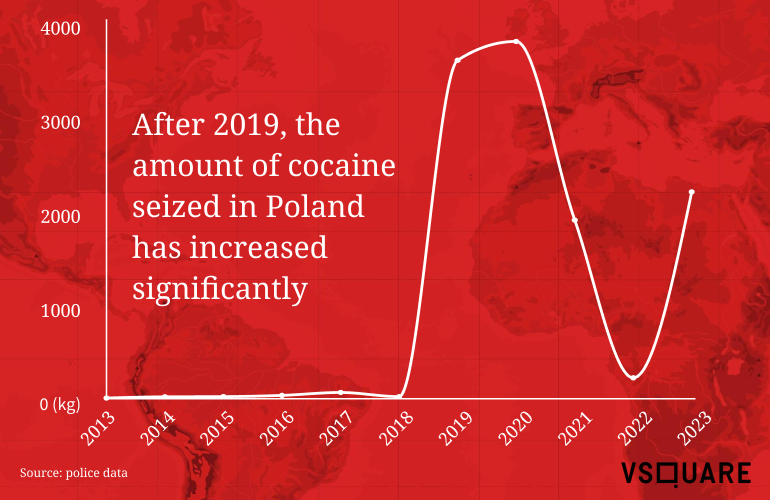

Poland has, for years, been one of the transit countries. Drugs that were not found by customs officers in Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain or France reach Gdynia, Gdansk, and Szczecin—Poland’s three largest international ports—by sea. In 2020, 3.8 tons were seized in our country.

To see what the fight against smuggling looks like up close, we went to the Port of Gdynia.

It was early October 2023. A green container from Vietnam came in for inspection, because drugs can, and often do, come from the Far East to our part of the world in such 30-ton containers.

Officers controlling the cargo in the port of Gdynia. Source: FRONTSTORY.PL

“The port of Rotterdam managed to intercept more than 70 tonnes of cocaine in 2021. This is still a good result, as only a small proportion of the containers are inspected,” explained Mariusz Majewski, deputy chief of the Maritime Crime Suppression Division of the Pomeranian Customs and Fiscal Office in Gdynia. According to estimates, 2 percent of all incoming containers are inspected at ports each year. And 10 million of them arrive in Rotterdam annually.

A small percentage of cargo is inspected so as not to disrupt logistical processes. There is no way to inspect it all.

Poland: a smuggling hub

Until recently, cocaine mainly flowed into Europe from ports in Colombia (still the main exporter of the drug). According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Colombians are increasingly shipping cocaine through Central America and South American countries. Cocaine from landlocked Bolivia and from Peru is increasingly being transported through the so-called southern cone, the region of the southernmost South American countries. From there, the drugs flow to Europe.

“Poland has always been a kind of ‘hub’ for drug trafficking. Recently, this role has been further strengthened by what is happening across the eastern border,” said Majewski. Some of the Ukrainian ports have closed. It used to be the case that shipments from South America would arrive in Ukraine, go along the Balkan route, and eventually find their way to Germany and beyond. When this route closed, smugglers began to look for alternatives.

Statistics on cocaine seizures in Poland, which we received from the Central Investigation Bureau of Police (CBŚP), speak volumes about Poland’s role in the cocaine trade. They indicate that the most important smuggling route is the sea route and that criminals concentrate at ports. Recent years (with the exception of 2022) have seen a spike in the amount of cocaine seized at ports.

Chalk with an insert

Customs officials told us that, from one ton of cocaine, an efficient distributor can make three WHAT. -”80, 90 percent pure cocaine is being imported into Europe. The 20, 30-percent stuff ends up on the streets,” added Majewski. The further away from Western Europe, where cocaine arrives in a purer form, the lower the price.

In special laboratories, the pure product from Colombia is mixed with various ingredients: baking powder, flour, chalk.

In December 2019, the CBŚP got a tip-off: a ship with a container loaded with bags of chalk had entered the port of Gdynia. First, a tracking dog got to work. A specialist scanner wasn’t far behind. It turned out that 1850 kg of cocaine were hidden in 74 of the 1600 bags aboard the ship. Their market value is over PLN 2 billion.

The CBŚP has spent years investigating the group responsible for the smuggling. Therefore, at the same time as the action at the port, officers entered a warehouse and a laboratory in two towns in the province of Wielkopolska. Four Colombians and an Iranian had arrived there a few days earlier from Germany. In the warehouse and laboratory, which are a few dozen kilometers apart, the criminals collected and processed drugs.

The Provincial Public Prosecutor’s Office in Gdansk has been investigating the lab technicians for four years, but does not want to reveal details concerning the methods authorities use to track down the criminals or when the case will be closed and the smugglers be brought to justice.

Poland – a drug mixing plant

The above CBŚP operation shows the role that Poland plays for the drug industry. According to Europol’s 2022 report, Poland is also one of the places to which criminals come to source cocaine-mixing chemicals.

“There are many indications that the chemicals seized in cocaine laboratories in the Netherlands were purchased in EU countries, including Germany, Poland and Spain. This means that these chemicals are likely to be of higher quality than those used in Colombian cocaine laboratories.”

In the past, cocaine was mixed with chalk. Today, it is more often combined with fish food or agricultural lime. “To detect such smuggling, a special device, known as a spectrometer, is needed. Using a laser beam, it detects molecules of narcotic substances. But the beam has to hit this particle, so there are a lot of attempts,” explained a customs official.

Customs officers from Gdynia talked about various smuggling methods. One of the most interesting is the “Trojan horse” method: the cartel brings its people into the port, from which the drugs are to sail out into the world. The cartel’s people are themselves hidden in a container. At a convenient time, they come out and move the drugs from their container into one that will sail to Europe. After the job is done, they return to the container, which someone then moves outside the gate.

The containers are equipped with toilets and enough space to sleep.

Corrupt, intimidated

According to a 2023 joint report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and Europol, gangsters mainly gain access to ports by bribing various figures. But sometimes they manage to employ themselves in the port.

Another common method is the “rip-off.” The cartels tear off the original seal with which the container is secured, pack the drugs between the legitimate goods, secure it with scanner-blocking materials, and seal the container back up using their own seal. Italy’s ‘Ndranghetta is considered to be the pioneer of this method. Gioia Tauro, located in Calabria, was one of the first ports to see Italian criminals use this technique. But though Italian in origin, this method was quickly replicated by other groups.

Drugs are easily concealed in the containers in which food is transported, i.e. refrigerated warehouses. Criminals stuff cocaine into the components of the refrigeration mechanism. Such cargo is difficult to detect when scanning the container because it is surrounded by steel. Polish customs officials tell us that this is also why drugs are hidden in agricultural machinery, finished bridge spans, or engines being transported for repair.

Drug panels

The largest cargo intercepted by Port of Gdynia customs officials? Four containers, each with ten 1-ton “big bags” (large transport bags), and in each of them a product with a clay-like consistency. Each big bag was wrapped with thick tape so that the suspicious goods could not be detected by the scanner. But the customs officers already had information about the suspicious transport. They unloaded the “clay” by hand throughout the day. Its composition had to be checked in the laboratory. The containers did not reach the consignee and were waiting at the terminal when the results came from the laboratory: there was heroin in the big bags. In August, officials also found almost half a ton of cocaine in floorboards.

Shipping containers in the port of Gdynia. Source: FRONTSTORY.PL

The customs officers cooperate with other services: the Polish Central Investigation Bureau of Police; Europol; Interpol; and a cell of the American DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) based in Gdansk. Americans prefer to work quietly. We have asked the DEA to talk to us for this piece several times, but to no avail.

Gdynia customs officials finished work on a container from Vietnam. They closed and bolted the door, securing it with a new seal. They filled out a report. This time, they found no drugs.

Surprise in the stomach

Over the past 20 years, Polish involvement in international criminal groups has mostly been reduced to that of petty smugglers.

In the documents from Colombia we find several threads confirming this. One concerns a Pole detained at Bogota airport with almost 3.5 kg of narcotics. The man was arrested in 2021. Another case dates back to 13 years ago and concerns the interception of a load of cocaine smuggled by an international network that included a Pole.

Polish prosecutors have asked Colombian prosecutors for legal assistance. “Between 2011 and 2022, 17 requests for legal assistance were made to Colombia. During this period, Colombian authorities made one request for legal assistance,” the press office of the National Prosecutor’s Office informed us. The most serious cases concerned not drugs but money laundering.

In 2013, the CBŚP unit from Wrocław, Poland tracked down a group that was trafficking in drugs and illegal cigarettes. The officers discovered that several people had traveled to Aruba on behalf of the group. While there, they were supposed to swallow condoms soaked in a substance containing cocaine. When they returned and expelled the condoms, chemists working for the group recovered the cocaine.

The smugglers, out of fear for their health, choose not to swallow the condoms. They returned without the cocaine or smuggled it in another way. Only Zbigniew Z. swallowed his share. Shortly after returning from Aruba, he died in a restroom in a shabby hotel in central Poland. The case did not arouse suspicion; it looked like an unfortunate accident. Years later, the investigators connected the dots and the prosecutor ordered the exhumation of the body. They discovered cocaine-covered condoms in Zbigniew Z.’s intestines.

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Mariusz Sepioło previously published reports and interviews in Tygodnik Powszechny and Polityka, among other publications. He is the author of several non-fiction books: Clerics, Himalayan Women, People and Reptiles, and Nationalists.

Konrad Szczygieł is an investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL. Previously, he was a reporter at Superwizjer TVN and OKO.Press. Since 2016, he has worked with Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He was shortlisted for a Grand Press award (2016, 2021) and an Andrzej Woyciechowski award (2021). He is based in Warsaw.

A Warsaw-based investigative and data journalist at VSquare and Frontstory.pl, Anastasiia Morozova previously collaborated with leading media outlets in Ukraine (Radio Free Europe, Slidstvo.info). She was shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2022) and was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.